Battle of Magnesia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Magnesia |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Seleucid War | |||||||

Illustration of a bronze plaque from Pergamon, likely depicting the Battle of Magnesia |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Seleucid Empire | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Battle of Magnesia was a major fight in ancient times. It happened in December 190 BC or January 189 BC. This battle was part of the Roman–Seleucid War. It was fought between the powerful Roman Republic and the Seleucid Empire.

The Roman army was led by Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus. They were joined by their allies from the Kingdom of Pergamon, led by King Eumenes II. They faced the Seleucid army, commanded by Antiochus III the Great. The battle took place near Magnesia ad Sipylum in what is now Manisa, Turkey.

Both armies spent days trying to get the best position. When the fighting began, King Eumenes' forces caused big problems for the Seleucid army's left side. Even though Antiochus' cavalry fought well on his right side, the middle of his army collapsed. This happened before he could send help. The battle ended with a clear victory for the Romans and Pergamon. This win led to the Treaty of Apamea, which greatly reduced the Seleucid Empire's power in Asia Minor.

Contents

What Led to the Battle?

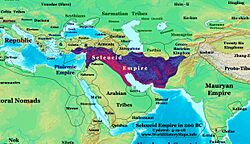

Empires Clash: Rome and the Seleucids

After his travels, King Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire made a deal with Philip V of Macedon. They planned to take over lands belonging to the Ptolemaic Kingdom. In 198 BC, Antiochus won a war and took control of a region called Coele-Syria. This made his southern border safe.

Then, Antiochus looked towards Asia Minor, which is modern-day Turkey. He attacked cities controlled by the Attalid family. Cities like Smyrna and Lampsacus worried Antiochus would take over everything. So, they asked the Roman Republic for help.

In 196 BC, Antiochus' troops crossed into Europe. They started rebuilding the important city of Lysimachia. Roman diplomats met Antiochus there. The Romans told him to leave Europe and let the Greek cities in Asia Minor be free. Antiochus argued that he was just taking back lands that belonged to his ancestors. He also said Rome shouldn't get involved in Asia Minor's affairs.

Hannibal's Role and Greek Allies

Around 196 BC, Carthaginian general Hannibal fled to Antiochus' court. Hannibal was a famous enemy of Rome. Even with Hannibal there, the Roman Senate tried to avoid war.

Meanwhile, the Seleucids expanded their lands in Thrace. Talks between Rome and the Seleucids kept failing. In 193 BC, the Aetolian League promised Antiochus they would fight with him against Rome. Antiochus also quietly supported Hannibal's plans against Rome.

The Aetolians then encouraged Greek states to rebel against Rome with Antiochus' help. They captured the city of Demetrias. In September 192 BC, an Aetolian general convinced Antiochus to openly fight Rome in Greece. Antiochus prepared an army of 10,000 foot soldiers, 500 horsemen, 6 war elephants, and 300 ships.

The Road to Magnesia

Antiochus' army landed at Demetrias. The Achaean League and then the Romans declared war in November 192 BC. Antiochus made Chalcis his main base in Greece. He tried to get Philip V of Macedon to join him again. But Philip had been beaten by Rome before and wanted to stay on Rome's good side. So, Philip joined the Romans instead.

Between December 192 and March 191 BC, Antiochus fought in Thessaly and Acarnania. But the Romans and Macedonians quickly took back all his gains. On April 26, 191 BC, Antiochus' army was badly defeated at the Battle of Thermopylae. He quickly returned to Ephesus.

The Seleucids then tried to destroy the Roman fleet. But the Romans won the Battle of Corycus in September 191 BC. This allowed them to control important cities on the Hellespont. In May 190 BC, Antiochus attacked Pergamon, forcing King Eumenes to return from Greece.

Later, the Rhodians defeated Hannibal's fleet. A month after that, a Roman-Rhodean fleet beat the Seleucids at the Battle of Myonessus. The Seleucids could no longer control the Aegean Sea. This opened the way for Rome to invade Asia Minor. Antiochus pulled his armies back and offered to pay Rome and meet their earlier demands. But by then, Rome wanted to completely defeat the Seleucids.

The Roman forces joined with Eumenes' army near the River Caecus. Antiochus prepared for a final, decisive battle.

Who Fought? Armies at Magnesia

Historians like Livy and Appian wrote about the armies at Magnesia. They both said the Roman army had about 30,000 men. They also claimed the Seleucids had around 72,000 soldiers. Modern historians disagree, with some thinking both armies might have had about 50,000 men. The Romans had 16 war elephants, while the Seleucids had 54.

There's a famous story about Antiochus and Hannibal. Antiochus supposedly asked Hannibal if his huge army was enough to beat the Romans. Hannibal replied, "Quite enough for the Romans, however greedy they are." This meant the army was big enough, but the Romans were very strong.

The Seleucid Army

The Seleucid army was very diverse. On their left side, commanded by Antiochus' son Seleucus, were slingers, archers, and different types of foot soldiers. There were also light cavalry, royal cavalry, and heavily armored horsemen called cataphracts. Sixteen war elephants were also on this side.

The middle of the Seleucid army had a huge Macedonian phalanx of 16,000 men. A phalanx was a tight formation of soldiers with long spears. Twenty war elephants were placed in pairs within the phalanx.

Antiochus himself led the right side. This wing had more cataphracts, elite cavalry, and royal guards. There were also horse archers, regular archers, and light foot soldiers. Sixteen more war elephants were kept in reserve. In front of the main army, there were scary scythed chariots and camel-riding archers.

The Roman and Pergamene Forces

The Roman army was smaller but well-organized. Their left side had 10,800 heavy infantry soldiers. These were Romans and their allies, along with four groups of cavalry.

The center also had 10,800 Roman and Latin heavy infantry. Scipio himself commanded them. Roman foot soldiers fought in three lines. They used a more open and flexible formation than the Seleucids.

King Eumenes led the Roman right side. This part had 2,800 to 3,000 cavalry, mostly Romans, with 800 men from Pergamon. In front of the main Roman force were light foot soldiers and archers. The back of the army had 2,000 volunteers and 16 African war elephants. These were thought to be not as good as the Asian war elephants used by the Seleucids.

The Battle Unfolds

Setting the Stage

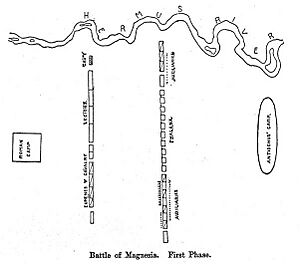

The battle happened in late 190 BC or early 189 BC. The Romans marched towards Thyatira, expecting to find Antiochus there. But Antiochus wanted to fight on ground he chose. His army moved to Magnesia ad Sipylum, setting up camp northeast of the city.

The Romans then moved their camp to a plain shaped like a horseshoe. This plain was surrounded by rivers on three sides. The Romans hoped this would limit the powerful Seleucid cavalry. Antiochus sent small groups to try and draw the Romans out, but they refused.

For five days, the armies lined up but did not fight. Scipio, the Roman commander, was in a tough spot. He couldn't attack the strong Seleucid camp directly. But if he didn't fight, his supply lines could be cut by the larger enemy cavalry. He also wanted a clear victory before a new Roman leader replaced him.

Chaos on the Left Flank

The battle began on the Seleucid left side. King Eumenes sent his archers, slingers, and spearmen forward. They attacked the Seleucid scythed chariots. These chariots panicked and fled after taking many hits. This caused confusion among the camel archers and cataphracts behind them.

Eumenes quickly charged with his cavalry. The Seleucid cataphracts couldn't get organized and fled to their camp. At the same time, the Roman center and right attacked the Seleucid foot soldiers on the left. This made them retreat, leaving the main Seleucid phalanx exposed.

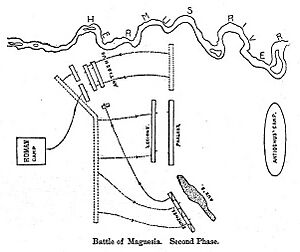

The Center and Right Flank

On the Seleucid right side, Antiochus led his cataphracts and elite cavalry. They attacked the Roman foot soldiers. The Roman soldiers broke formation and retreated to their camp. There, they were reinforced and rallied by a Roman officer. Antiochus' cavalry got stuck fighting around the Roman camp. This was a problem because his forces were needed elsewhere.

In the middle, the Seleucid phalanx stood strong against the Roman foot soldiers. But the phalanx was too slow to stop the Roman archers and slingers. These Roman fighters kept showering the phalanx with arrows and stones. The war elephants within the phalanx panicked because of the projectiles. This caused the phalanx to break its tight formation.

The Seleucid phalanx soldiers threw away their weapons and ran from the battlefield. By the time Antiochus' cavalry returned to help the center, his army was already scattered. Antiochus gathered the remaining troops and retreated to Sardes. The Romans were busy looting his camp.

What Happened After? The Treaty of Apamea

Antiochus' defeat at Magnesia was a huge turning point. It showed that the Macedonian phalanx, a famous fighting style, was no longer the best. Ancient sources say 53,000 Seleucid soldiers died, and 1,400 were captured. They also lost 15 elephants. In contrast, the Romans reportedly lost only 349 men. Modern estimates suggest around 10,000 Seleucid deaths and 5,000 Roman deaths.

Soon after the battle, Antiochus learned his son Seleucus had survived. They met at Apamea. The defeat at Magnesia caused many cities to surrender to the Romans. Antiochus sent his generals to ask for a truce.

The truce was signed in January 189 BC. Antiochus agreed to give up all his lands west of the Taurus Mountains. He also had to pay a large amount of money to Rome. He promised to hand over Hannibal and other enemies of Rome who were with him.

The Romans then wanted to control Asia Minor and punish Antiochus' allies. They fought the Galatian War. In Greece, they dealt with groups who broke earlier truces. In the summer of 189 BC, representatives from the Seleucid Empire, Pergamon, and Rhodes met with the Roman Senate.

The Romans gave Lycia and Caria to Rhodes. Pergamon received Thrace and most of Asia Minor west of the Taurus Mountains. Cities that had sided with Rome before the battle were guaranteed their freedom. Antiochus also agreed to remove all his troops from beyond the Taurus Mountains. He promised not to help Rome's enemies.

The terms also included handing over Hannibal and other important people as hostages. Antiochus had to destroy most of his fleet, keeping only ten ships. He also had to give Rome a large amount of grain each year. These terms became official in the summer of 188 BC with the signing of the Treaty of Apamea.

Sources

- Sarikakis, Theodoros (1974). "Το Βασίλειο των Σελευκιδών και η Ρώμη". In Christopoulos, Georgios A. (in Greek). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος Ε΄: Ελληνιστικοί Χρόνοι. Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 55–91. ISBN 978-960-213-101-5.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |