Roman–Seleucid war facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Roman–Seleucid war |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

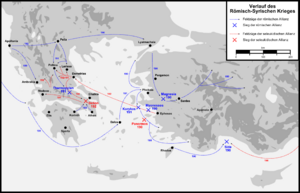

Asia Minor after the war |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

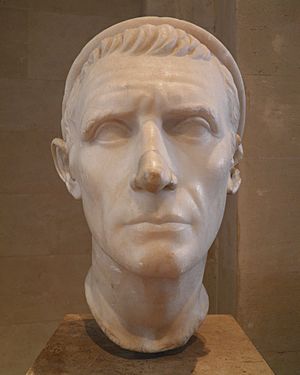

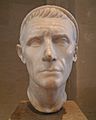

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

The Roman–Seleucid War (192–188 BC) was a big fight between two powerful groups. One group was led by the Roman Republic. The other was led by King Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire. This war is also known by other names, like the Aetolian War or Syrian War.

The battles happened in places like modern-day southern Greece, the Aegean Sea, and Asia Minor. The war started because of a "cold war" that began in 196 BC. During this time, Rome and the Seleucids tried to control different areas. They made alliances with small Greek city-states.

Rome thought Greece was their area of influence. They saw Asia Minor as a buffer zone. But the Seleucids believed Asia Minor was their main territory. They saw Greece as a buffer. These different ideas led to conflict.

The Aetolian League started a small war. This brought Antiochus into the fight. Soon, Rome and the Seleucids were clashing. Antiochus landed his army in Greece. But he was defeated at the Battle of Thermopylae. The Roman consul Manius Acilius Glabrio led the victory. Antiochus had to retreat across the Aegean Sea.

The Aetolians tried to make peace with Rome. But Rome's demands were too high. Antiochus' navy was defeated in two big sea battles. This gave the Roman side control of the sea. Then, the Roman consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio chased Antiochus into Asia Minor. King Eumenes II of Pergamum helped the Romans.

Antiochus tried to talk peace, but Rome's demands were still too much. He broke off talks. But after losing the Battle of Magnesia, he had to accept Rome's terms. The peace treaty was signed in Apamea. Antiochus gave up all his lands beyond the Taurus mountains to Rome's allies. He also paid a huge amount of money to cover Rome's war costs.

The Aetolians made their own peace deal with Rome. They became a state controlled by Rome. Rome then became the main power over Greek city-states. This included those in the Balkans and Asia Minor. The Seleucids were mostly kept out of the Mediterranean Sea.

Contents

Why the War Started

From 212 to 205 BC, King Antiochus III fought to regain control. He wanted to bring Armenia and Iran back into his empire. After making them his vassals, he signed treaties. He then focused on taking back parts of Asia Minor.

But then, Ptolemy IV Philopator of Egypt died in 204 BC. This gave Antiochus a chance to take lands from Egypt. He took Coele Syria, Phoenicia, and Palestine. After these victories, he returned to Asia Minor around 197 BC. He was so successful that he took the title "Great King."

Now, two big powers were on either side of the Aegean Sea. Rome was in the west, and Antiochus was in the east. Rome's power grew after the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC). This war was against Philip V of Macedon. Philip had attacked islands and declared war on Rhodes and Pergamum. These places asked Rome for help.

The Roman Senate decided to send an ultimatum to Philip. Over the next three years, Rome fought Philip and won. After this, the politics of the Aegean changed a lot. Rome's allies had defeated Philip. But Antiochus was also making his empire stronger in western Asia Minor.

During the Macedonian War, Rome and Antiochus were friendly. Antiochus promised not to help Philip. He also pulled his troops out of Pergamum, a Roman ally. Rome did not stop him from taking lands further east in Asia Minor.

But after the war, Rome's opinion of Antiochus changed. He crossed into Europe, threatening Rome's allies. He also congratulated Rome late on their victory. Rome then declared four towns free, even though they were near Antiochus' lands.

Rome also said all Greeks should be free. This included Greeks in Asia Minor under Antiochus' rule. Rome warned Antiochus not to interfere in Greek affairs. They also told him not to enter Europe. This warning was given at the Isthmian Games in 196 BC.

Later, Roman ambassadors met Antiochus. They demanded he leave Ptolemaic lands in Asia Minor. They also wanted him to leave lands that used to belong to Philip. And they said he should not attack any Greek cities. Antiochus said Rome had no right to make these demands. He pointed to his historical claims in the region. He also said he had already declared Greek cities in Asia Minor free.

The main problem was that Rome and Antiochus had different ideas. Rome saw its influence reaching the Hellespont. They saw Asia Minor as a buffer. Antiochus saw Asia Minor as his main area. He saw Greece as a buffer. Rome tried to gain support from Greek states. This way, if Antiochus attacked, Rome would look like the good guy.

War Breaks Out

Roman forces in Greece mostly left after 195 BC. Rome said Greece was free from Roman control. At the same time, Antiochus had a large army in Europe. He was fighting tribes in Thrace. He saw Rome's withdrawal as a chance to expand.

Roman and Antiochus' envoys met in Rome. Roman officials made their position clear. If Antiochus wanted peace, he had to stay on his side of the Hellespont. If not, Rome would protect its allies in Asia. One Roman official, Flaminius, publicly said Rome wanted to free Greeks in Asia Minor. Antiochus' ambassadors could only ask for more talks. By spring 192 BC, Rome said peace was possible if Antiochus stayed in Thrace.

In late 193 BC, the Aetolian League wanted to change things. They wanted to start a war between Rome and Antiochus. They hoped to gain from it. The Aetolians tried to form an alliance. They wanted Philip of Macedon and Nabis of Sparta to join them.

The alliance plan failed. But Nabis was convinced to attack coastal cities. The nearby Achaean League sent troops. They also sent ambassadors to Rome. Rome sent four ambassadors to Greece. After Flaminius spoke to the Aetolian League, they invited Antiochus. They asked him to free Greece from Roman rule. This was a declaration of war.

The Aetolians then tried to take Sparta, Chalcis, and Demetrias. They only succeeded at Demetrias. They killed Nabis in Sparta, but the Achaeans stopped them. Chalcis fought back against the Aetolians. The Aetolians convinced Antiochus that Greek cities wanted to rebel. So, Antiochus landed at Demetrias. He announced he would free the Greeks from Rome.

This was the final straw for Rome. The Aetolians and Antiochus interfering in Greece was unacceptable. Rome sent a fleet to the Peloponnese. They also sent two legions to Epirus. More troops were gathered. In 191 BC, Manius Acilius Glabrio was put in charge. He was to lead the war against Antiochus.

The War Begins

Even before Glabrio's army arrived, Antiochus' campaign was not going well. The Greeks did not welcome him warmly. Rome's promise of freedom seemed more real than Antiochus' claims. He had to use force to "free" some cities in Thessaly. The Achaean League declared war on him. They did this because of their alliance with Rome.

Battle of Thermopylae

In the spring of 191 BC, the Macedonians joined the war. They fought against the Aetolian League. They took several towns in Thessaly. Antiochus moved towards Acarnania. But he had to pull back when he heard about the Thessaly attacks.

When Consul Glabrio reached Thessaly, towns surrendered easily. Antiochus had no reinforcements. He was greatly outnumbered by the Roman forces. He had to choose between retreating or fighting where his small army would have a chance. He chose Thermopylae.

The battle was a huge defeat for Antiochus. He immediately fled Greece for Ephesus. Less than six months had passed since he arrived in Demetrias. After Rome's victory, Greek cities quickly joined the winning side.

Glabrio then focused on the Aetolians. He captured Heraclea that year. He then began to besiege Naupactus. Peace talks with the Aetolians failed. Glabrio was replaced by Lucius Cornelius Scipio in 190 BC. Lucius' brother, Scipio Africanus, was also a skilled leader. Glabrio returned to Rome and celebrated a victory parade.

That year, the Roman fleet won a battle near Corycus. Antiochus' fleet had to retreat to Ephesus. The Seleucids then built a new fleet in Cilicia. Hannibal, who had fled to Antiochus' court, was put in command.

The Scipios could not cross the Aegean directly. They stayed in Europe. They arranged a six-month truce with the Aetolians. This allowed the Aetolians to send envoys to Rome for peace talks. Meanwhile, the Scipios marched by land towards Asia Minor.

Hannibal's fleet was stopped by the Rhodians at the Battle of the Eurymedon. The remaining Seleucid fleet at Ephesus was destroyed. This happened in the Battle of Myonessus. This battle gave Rome control of the sea. Antiochus had to quickly retreat across the Hellespont into Asia Minor. When the Romans advanced, Antiochus' allies did not stop them. He offered no fight when they crossed into Asia Minor.

Battle of Magnesia

By October 190 BC, Antiochus' navy was no match for Rome's. The Scipios had arrived in Asia Minor. Antiochus tried to negotiate for peace. He offered to pay half of Rome's war costs. He also offered to give up his claims to some Roman allied cities.

But the Scipios refused. They wanted Antiochus to give up all of Asia Minor northwest of the Taurus mountains. They also demanded he pay all of Rome's war costs. Antiochus thought these demands were too extreme. So, he broke off the talks.

Later that year, around mid-December, the main battle happened. It was near Magnesia ad Sipylum. Consul Lucius Scipio wanted to fight soon. He needed a victory before his command ended in December. The Battle of Magnesia was a clear victory for the Roman side.

The exact number of soldiers is debated. Some say Antiochus had 60,000 foot soldiers and 12,000 horsemen. The Roman side had about 30,000. But others believe both sides had around 50,000 men.

Lucius Scipio was the official Roman commander. But his brother, Scipio Africanus, claimed to be sick. Some say Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus was actually in charge. The battle began with the Roman side breaking Antiochus' chariots. Then, Eumenes II led a cavalry charge. This pushed Antiochus' heavy cavalry into his own center.

Antiochus was leading his own cavalry wing. He had pushed back the Roman left side. So, he could not help his main infantry. Antiochus' foot soldiers fought hard. But their own elephants disrupted their lines. Eumenes used these gaps to attack. He destroyed Antiochus' main army from the side.

With his armies defeated, Antiochus sent people to talk peace. They met the Scipios at Sardis, where the Romans had moved.

Peace for Aetolia

In Greece, the war continued. Marcus Fulvius Nobilior became consul in 189 BC. He was assigned to continue the war after talks failed again. He besieged Ambracia. Later that year, he made a final peace deal. This was with both the Aetolians and the Cephallenians.

The Aetolians faced high Roman demands at first. Rome wanted 1,000 talents, which was too much. But Rhodes helped mediate. They convinced Rome to lower the demand. The Aetolians agreed to pay 200 talents immediately. They would pay another 300 over six years. Aetolia also became a state controlled by Rome. They had to serve the Roman people.

The other consul for 189 BC, Gnaeus Manlius Vulso, took over from the Scipios in Asia. He found a truce with Antiochus. He then led an expedition into Anatolia. This was to subdue the Galatians. They had supported Antiochus.

The Peace of Apamea

After the Battle of Magnesia, Antiochus' representatives went to Sardis. This is where the Romans were camped. They accepted Rome's peace terms. These terms were now more specific. Antiochus had to give up all territory north and west of the Taurus mountains.

He also had to pay 15,000 Euboeic talents. He would pay 500 right away, 2,500 after Rome approved, and the rest over twelve years. Eumenes of Pergamum would get 400 talents and grain. Roman enemies hiding at Antiochus' court, like Hannibal, had to be handed over. And twenty hostages, including Antiochus' youngest son, would go to Rome. This was a guarantee.

What the Treaty Said

We know about the treaty details from writings by Polybius. The exact terms were first worked out in Rome. Ambassadors from Asia Minor gave their input. Eumenes visited in person. Later, the Roman consul in Asia, Manlius Vulso, finalized them. He was helped by ten Roman senators.

In Rome, it was decided that Greeks in Asia Minor would not be treated like those in Europe. Instead, Rome would reward Eumenes of Pergamum and Rhodes. They would get land for helping in the war. Eumenes and the Rhodians had different ideas. Eumenes thought Rome should control Antiochus' former lands. If Rome didn't want to, he felt he was the next best choice. Rhodes argued that Greeks should be free. They said Eumenes should get Antiochus' non-Greek lands.

The Roman Senate did not want to keep an army in Asia Minor. So, they gave Rhodes Lycia and Caria. Eumenes received the rest of the land.

Manlius Vulso defeated some Galatian Gauls in Anatolia. He took a lot of treasure from them. He then went to Pamphylia. There, he received the first large payment from Antiochus. He then moved to Apamea. There, he and the senators clearly defined the Taurus mountain line.

They also limited Antiochus' navy. He could only have ten large ships. He also could not use war elephants. He was forbidden from sailing past Cape Sarpedon. Manlius Vulso and Antiochus then swore to the treaty. They divided the cities in Asia Minor. Cities that were Roman allies stayed independent. The rest went to Pergamum and Rhodes. Antiochus' lands in Europe also went to Pergamum. But the cities of Aenus and Maronea were made free again.

The treaty aimed to neutralize outside influences in Roman areas. It also aimed to strengthen Rome's friends. The winners in Asia, Pergamum, Rhodes, and the free cities, were grateful to Rome. Rome wanted to bring peace to the region through goodwill, not armies. So far, they had succeeded.

What Happened Next

The lands that used to belong to Antiochus were divided right after the treaty. This greatly helped Eumenes. He later supported Rome against Macedon. But this also meant Rome no longer needed him as much. By 168 BC, Rome changed its alliances. They turned against both Pergamum and Rhodes.

Rome continued to enforce some parts of the treaty with Antiochus. But the rules about war elephants and navy size mostly ended when Antiochus died. The rule about not sailing past Cape Sarpedon also faded.

A Buffer for the Seleucid Empire

Antiochus accepted the terms quickly after Magnesia. He believed more war would ruin both empires. Antiochus still had many men and land to trade for time. But giving up Asia Minor created a huge buffer zone. This led to a long peace between Rome and the Seleucid empires.

Rome did not try to fight the Seleucids again. They did not have a strong foothold in Asia Minor yet. Antiochus still had a reputation as a skilled commander. Instead, Rome tried to weaken the Seleucids through diplomacy. They used threats and bribes. They encouraged smaller states to declare war on the Seleucids. Roman interference made it hard for Antiochus' successors to control their western border. In the eastern Seleucid empire, the Parthians and Bactrians declared independence. This was the only war Rome fought with the Seleucids. The Seleucid empire fell apart a generation later.

Rules About Weapons

After Antiochus died on July 3, 187 BC, his successor, Seleucus IV Philopator, started rebuilding his navy. He did not provoke Rome. Antiochus' successors could also raise large armies. The treaty terms did not cause the Seleucid military to collapse.

Seleucus IV's successor, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, simply ignored the treaty's weapon rules. By 168 BC, his navy was strong enough to invade Cyprus. This was west of Cape Sarpedon. He also had elephants and mercenaries. Some sources say Rome tried to enforce the rules after Antiochus IV died. They burned Seleucid ships and harmed elephants. But Rome had known about these ships and elephants for two decades. Historians suggest Rome acted for military gain, not just treaty enforcement.

Rome was friendly with the Seleucids in the mid-second century. A Roman embassy saw elephants in Antioch. But they did not mention the treaty to the Senate. This shows the rules were not strictly enforced. However, the rules about Rome's influence in Asia Minor were followed. When Seleucus IV gathered an army, Rome likely reminded him not to attack Roman allies. The payments for the war were also completed. They were paid slightly late during Antiochus IV's rule in 173 BC.

Generally, only the rules about giving up land and paying money were strictly enforced. Other rules, like those in similar treaties, applied to the ruler, not the state. So, these rules ended when a ruler died.

Hostages and Captives

Antiochus III's youngest son, also named Antiochus, was sent to Rome as a hostage. After Antiochus III died, he was exchanged for Demetrius. Demetrius was Antiochus' nephew. He was held in Rome for sixteen years. He later escaped and took the throne in 162 BC.

Hannibal was supposed to be given to Rome under the treaty. But he fled to Crete and then to Bithynia. Flaminius negotiated with the king of Bithynia to get Hannibal. In 183 or 182 BC, Hannibal killed himself. One Aetolian leader, Thoas, was also handed over to Rome. He was later released. He became a leader in Aetolia twice more.

Images for kids

See also

- List of conflicts in the Near East

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |