Phrygia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Phrygia

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1200–675 BC | |||||||||||||||

Map of the Phrygian Kingdom when it was largest, around 700 BC.

|

|||||||||||||||

| Capital | Gordion | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Phrygian | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Phrygian religion | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Kings | |||||||||||||||

|

• 8th Century–740 BC

|

Gordias | ||||||||||||||

|

• 740–675 BC

|

Midas | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||||||

| 1200 BC | |||||||||||||||

|

• Fall to the Cimmerians

|

675 BC | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Phrygia was an ancient kingdom in the west-central part of Anatolia, which is now the country of Turkey. It was centered around the Sangarios River.

Many famous Greek myths tell stories about legendary Phrygian kings. These include:

- Gordias, who tied the famous Gordian Knot. It was said that whoever could untie it would rule Asia.

- Midas, who was famous for his "golden touch" that turned everything he touched into gold.

- Mygdon, who fought a war against the Amazons, a mythical tribe of warrior women.

According to Homer's epic poem, the Iliad, the Phrygians were allies of the Trojans in the Trojan War. They fought against the Greek Achaeans.

The Kingdom of Phrygia was most powerful in the 8th century BC under another king also named Midas. He was a real historical figure who ruled over most of western and central Anatolia. However, this Midas was the last independent king of Phrygia. Around 695 BC, invaders called the Cimmerians attacked and destroyed the Phrygian capital, Gordion.

After that, Phrygia was ruled by other kingdoms, including Lydia, Persia, Alexander the Great's empire, and the Roman Empire. Over time, the Phrygian people became Christians and started speaking Greek. Eventually, the name "Phrygia" was no longer used for the region.

Geography

Phrygia was located on a high, dry plateau in Anatolia. This land was very different from the forests to its north and west. The area had hot summers and cold winters, which made it difficult to grow crops like olives. Instead, the land was mostly used for raising animals like sheep and for growing barley.

The capital city of Phrygia was Gordion. Another important settlement was Midas City, which was located in an area with hills and strange columns of volcanic rock.

The southern part of Phrygia had more water from the Maeander River (now called the Büyük Menderes River). This allowed cities like Laodicea and Hierapolis to grow.

Origins

Where did the Phrygians come from?

Ancient Greek historians like Herodotus wrote that the Phrygians originally came from the Balkans in Europe. He said they were called the Bryges before they moved to Anatolia. Legends about King Midas also connect him to this region.

Some modern historians have a different idea. They think the Phrygians might have moved into Anatolia around 1200 BC, after the great Hittite Empire collapsed. This theory suggests they might have been one of the groups known as the "Sea Peoples" who caused a lot of change in the ancient world.

The Phrygian Language

The Phrygian language was spoken until about the 6th century AD. It was an Indo-European language, which means it was related to languages like Greek and Latin. Inscriptions found at Gordion show that Phrygian had some words that were similar to Greek.

However, Phrygian was very different from the languages of its neighbors in Anatolia, like the Hittite language. This difference is one reason why many historians believe the Phrygians came from Europe.

History

The Kingdom at its Peak

In the 8th century BC, Phrygia became a powerful empire under King Midas. Its capital was at Gordion. The kingdom grew to control most of central and western Anatolia. It was so powerful that it competed with the great empires of Assyria and Urartu.

This historical King Midas is mentioned in Assyrian records as "Mita." He seems to have had good relationships with the Greeks and even married a Greek princess. During his reign, the Phrygians developed their own writing system, which used an alphabet similar to the one used by the Greeks.

Invasion and Destruction

The powerful Phrygian Kingdom came to a sudden end. Around 675 BC, invaders from the north called the Cimmerians swept through Anatolia. They attacked Gordion, burning it to the ground. According to legend, King Midas took his own life after the defeat.

Archaeologists digging at Gordion have found evidence of this violent destruction. They also discovered a magnificent tomb from that time, popularly called the "Tomb of Midas." Inside, they found a wooden burial chamber with furniture, a coffin, and other valuable items.

Life Under Other Empires

Lydian and Persian Rule

After the Cimmerians destroyed Gordion, the nearby kingdom of Lydia grew stronger. The Lydians eventually drove out the Cimmerians and took control of Phrygia.

In the 540s BC, the Persian Empire, led by Cyrus the Great, conquered Lydia. Phrygia then became a province of this vast empire. The Persians built a famous "Royal Road" that passed through Phrygia, making it an important trade route.

Alexander the Great and After

In 333 BC, the famous Greek conqueror Alexander the Great marched his army through Phrygia. When he reached Gordion, he faced the challenge of the Gordian Knot. Instead of trying to untie the complex knot, he simply cut it with his sword.

After Alexander's death, his empire was divided. Northern Phrygia was invaded by Celts from Europe, who created a new territory called Galatia. The old capital of Gordion was destroyed by these invaders, known as the Gauls.

Roman and Byzantine Rule

By 133 BC, what was left of Phrygia became part of the Roman Empire. The Romans divided Phrygia into different provinces for administrative purposes.

Phrygia was an important center for early Christianity. Visitors from Phrygia were in Jerusalem for the Pentecost, and the Apostle Paul traveled through the region.

Later, when the Roman Empire split, Phrygia was part of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. It remained under Byzantine rule until the 11th century, when Turks began to conquer Anatolia. By the 13th century, the region was fully under Turkish control, and the name Phrygia slowly fell out of use.

Culture

Religion

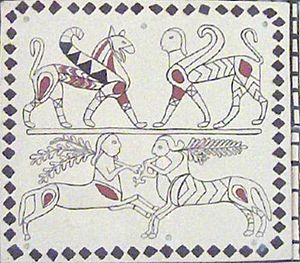

The most important deity for the Phrygians was a goddess named Matar Kubeleya, which means "Mountain Mother." She was often called Cybele by the Greeks and Romans. She was seen as the mistress of wild mountains, nature, and animals.

Worship of Matar Kubeleya often took place in the mountains. Her priests, called Corybantes, would perform wild, ecstatic dances with music from pipes and cymbals.

Another important god was Tiws, a sky and storm god, similar to the Greek god Zeus.

Music and Art

The ancient Greeks believed that many of their musical traditions came from Phrygia. The Phrygian mode was a type of musical scale that the Greeks considered warlike and exciting.

The Phrygians are also credited with inventing the aulos, a musical instrument with two pipes.

A famous symbol from the region is the Phrygian cap. This was a soft, cone-shaped cap with the top pulled forward. In ancient art, it was used to show that someone was from the East, like the Trojan prince Paris. Much later, this cap became a symbol of freedom during the American and French Revolutions, where it was known as a "liberty cap."

Famous Myths and Legends

Phrygia is the setting for many famous Greek myths.

The Gordian Knot

One of the most famous stories is about a farmer named Gordias. An oracle had told the Phrygians that their next king would be the first person to arrive at the temple in a cart. Gordias was that farmer, and he became king. He dedicated his ox-cart to the gods and tied it to a post with an incredibly complex knot. This became known as the Gordian Knot.

King Midas and the Golden Touch

Gordias's son was the legendary King Midas. According to myth, the god Dionysus granted Midas a wish. Midas wished that everything he touched would turn to gold. At first, he was thrilled, but he soon realized his mistake when his food and even his own daughter turned to gold. He begged Dionysus to take back the gift, and he was told to wash in the river Pactolus, which washed the "golden touch" away.

The Trojan War

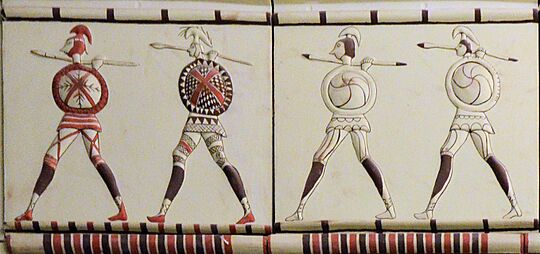

The Phrygians played a role in the stories of the Trojan War. The Trojan king, Priam, married a Phrygian princess named Hecuba. Because of this alliance, Phrygian warriors fought alongside the Trojans against the Greeks.

See also

In Spanish: Frigia para niños

In Spanish: Frigia para niños

- Ancient regions of Anatolia

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |