Battle of Thermopylae (191 BC) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Thermopylae |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Seleucid War | |||||||

View of the Thermopylae pass from the area of the Phocian Wall. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic | Seleucid Empire Aetolian League |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Manius Acilius Glabrio Marcus Porcius Cato Lucius Valerius Flaccus |

Antiochus III the Great | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000 to 30,000 | 12,500 16 war elephants |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12,000 16 war elephants |

|||||||

The Battle of Thermopylae happened on April 24, 191 BC. It was a major fight during the Roman–Seleucid War. In this battle, the powerful Roman Republic faced off against the Seleucid Empire and their allies, the Aetolian League.

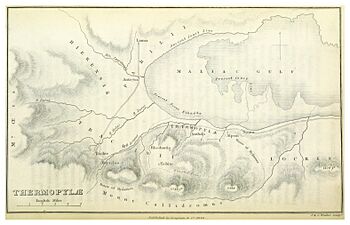

The Roman army was led by their general, Manius Acilius Glabrio. The Seleucid forces were commanded by their king, Antiochus III the Great. The battle took place at the famous Thermopylae pass in Greece. At first, the Seleucids held their ground, stopping many Roman attacks. But a small Roman group, led by Marcus Porcius Cato, found a secret path. They surprised the Aetolian guards at Fort Callidromus. This caused the Seleucid army to panic and break apart. Most of their army was destroyed. King Antiochus managed to escape with his cavalry and soon left Greece.

Contents

Why Did the Battle Happen?

After expanding his empire in Asia, the Seleucid King Antiochus III the Great wanted to control more land. He even made a deal with Philip V of Macedon to take over parts of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Antiochus won some wars and gained new areas, especially in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey).

Some independent Greek cities, like Smyrna and Lampsacus, worried about Antiochus's growing power. They asked the Roman Republic for help. Rome was also concerned about Antiochus moving his troops into Europe. Roman leaders told Antiochus to leave Europe and let the Greek cities in Asia Minor be free. But Antiochus said he was just rebuilding his family's old empire. He thought Rome should not interfere.

Around this time, Hannibal, a famous general who was Rome's old enemy, fled to Antiochus's court. This made Rome even more suspicious. Later, the Aetolian League in Greece promised to support Antiochus if he fought Rome. They wanted to start a war. In 192 BC, the Aetolians captured a key port city called Demetrias. They then convinced Antiochus to openly challenge Rome in Greece. Antiochus sent about 10,000 soldiers, 500 cavalry, 6 war elephants, and 300 ships to Greece.

Getting Ready for Battle

Antiochus's army landed at Demetrias. He met with the Aetolians, who made him their military leader for a year. The Achaean League and then the Romans declared war on Antiochus and the Aetolians. Antiochus took control of Chalcis, making it his main base in Greece. He tried to get Philip V of Macedon to join him, but Philip sided with Rome instead. Most other Greek states stayed neutral, fearing what would happen. Only a few, like Elis and the Boeotian League, joined Antiochus.

In December 192 BC, Antiochus and his Aetolian allies attacked Thessaly. They took over much of southern Thessaly before stopping for winter. In March 191 BC, Antiochus invaded Acarnania to gain control of ports on Greece's western coast.

Meanwhile, the Roman general Manius Acilius Glabrio arrived in Greece with a large army. He had 20,000 foot soldiers, 2,000 cavalry, and 15 war elephants. With other Roman and allied forces, the total Roman strength in Greece reached about 36,000 men. This was much larger than Antiochus's army. The Romans and their allies quickly took back the areas Antiochus had captured in Thessaly. When Antiochus heard about the Roman advance, he gathered his troops and returned to Chalcis.

Antiochus marched to Lamia with his entire force: 12,000 foot soldiers, 500 cavalry, and 16 war elephants. He asked the Aetolians to join him, but only 4,000 came. They were worried about their own homes being invaded. Because the Roman army was much bigger, Antiochus decided to retreat to the narrow Thermopylae pass.

The Aetolians split their forces to guard the roads to Aetolia and Thermopylae. Antiochus's troops took the narrowest part of the Thermopylae pass, which was only about 90 meters wide. They strengthened an old defensive wall that stretched up the hill for 1,800 meters. They also built a ditch and earthworks that reached the Malian Gulf. The slopes above the pass were manned with soldiers who could throw projectiles. Special towers were built for artillery. The Roman general Glabrio set up his camp near the "hot gates" in the pass.

The Battle Begins

Antiochus placed his main fighting force, the Macedonian phalanx, behind the strong rampart. His light infantry and special silver-shielded soldiers (argyraspides) stood in front of it. On his left side, he had archers and slingers. Antiochus himself led the cavalry on the right, positioned behind his war elephants. The Aetolians sent 2,000 soldiers to guard forts overlooking the pass. The Seleucid navy protected the coast. Antiochus planned to hold the pass until more soldiers arrived from Asia Minor.

Even though Antiochus had a strong defensive position, Glabrio decided to attack. He had a much larger army, with 25,000 to 30,000 soldiers. He sent 2,000 soldiers to attack Heraclea and kept 2,000 cavalry to guard his camp. On the night of April 23, 191 BC, Glabrio ordered Marcus Porcius Cato and Lucius Valerius Flaccus to lead 2,000 men each to attack the Aetolian forts. At dawn on April 24, Glabrio led the main Roman force of 18,000 soldiers in a direct attack through the pass.

The first Roman attack was pushed back by the Seleucid missile troops. But the Romans kept pushing. Their repeated attacks forced the silver-shielded soldiers and light infantry to fall back behind the rampart. However, the wall of long spears (sarissas) held by the Seleucid phalanx was too strong for the Romans to break through. Flaccus also struggled to make progress against the defenders of the other forts.

But Cato had a breakthrough. He found Callidromus at dawn, after getting lost during the night. The 600 Aetolian guards there were completely surprised and ran away to the Seleucid camp. Cato then attacked the Seleucid camp from behind. The Seleucids thought Cato's force was much bigger than it was. Their courage dropped, and they panicked. The entire army broke ranks and ran away in a disorganized retreat. Almost all of Antiochus's army was lost, except for Antiochus himself and his cavalrymen.

What Happened Next?

Antiochus was completely defeated on land and had lost touch with his navy. When he learned that Glabrio was advancing through Greece without any resistance, he quickly returned to Ephesus in Asia Minor. When the Seleucid soldiers at Chalcis followed their king back to Asia Minor, the cities in Euboea immediately welcomed the Romans as liberators.

The Seleucids then tried to destroy the Roman fleet before it could join with the fleets of Rhodes and Pergamum. But in September 191 BC, the Roman fleet defeated the Seleucids in the Battle of Corycus. This allowed Rome to control several important cities. Later, in May 190 BC, Antiochus invaded the Kingdom of Pergamon, forcing its king, Eumenes II, to return from Greece.

In August 190 BC, the Rhodians defeated Hannibal's fleet. A month later, a combined Roman and Rhodian fleet defeated the Seleucids again at the Battle of Myonessus. After these defeats, the Seleucids could no longer control the Aegean Sea. This opened the way for a Roman invasion of Asia Minor, leading to the end of the war.

Images for kids

Sources

- Sarikakis, Theodoros (1974). "Το Βασίλειο των Σελευκιδών και η Ρώμη". In Christopoulos, Georgios A. (in Greek). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος Ε΄: Ελληνιστικοί Χρόνοι. Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 55–91. ISBN 978-960-213-101-5.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |