Hellenistic Greece facts for kids

Hellenistic Greece is a time in history after Classical Greece. It started when Alexander the Great died in 323 BC. It ended when the Roman Republic took over the main parts of the Achaean League in Greece.

This takeover finished with the Battle of Corinth in 146 BC. Rome won a huge victory in the Peloponnese, leading to the destruction of Corinth. This began the time of Roman Greece. The Hellenistic period truly ended in 31 BC at the Battle of Actium. Here, the future emperor Augustus defeated Greek Ptolemaic queen Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony. The next year, Rome took over Alexandria, the last big center of Hellenistic Greek power.

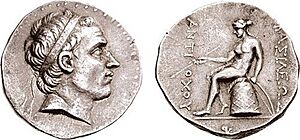

The Hellenistic period started with the wars of the Diadochi. These were fights among Alexander the Great's former generals. They wanted to divide his huge empire in Europe, Asia, and North Africa. These wars lasted until 275 BC. During this time, the old ruling families of Macedonia fell. A new family, the Antigonid dynasty, took power. This era also saw many wars between the Kingdom of Macedonia and its friends against the Aetolian League, Achaean League, and the city-state of Sparta.

During the rule of Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC), Macedonia faced many challenges. They lost the Cretan War (205–200 BC) to an alliance led by Rhodes. Also, their alliance with Hannibal of Carthage led them into the First and Second Macedonian War with ancient Rome. After these wars, Macedonia seemed weaker. This encouraged Antiochus III the Great of the Seleucid Empire to invade mainland Greece. But the Romans defeated him at Thermopylae in 191 BC and Magnesia in 190 BC. These wins made Rome the strongest military power in the area. Within about 20 years, after conquering Macedonia in 168 BC and Epirus in 167 BC, the Romans controlled all of Greece.

During the Hellenistic period, Greece itself became less important in the Greek-speaking world. The main centers of Hellenistic culture were Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria. Other important cities included Pergamon, Ephesus, Rhodes, and Seleucia. More and more cities grew in the Eastern Mediterranean during this time.

Contents

Macedonia's Role in Hellenistic Greece

The conquests of Alexander the Great changed the Greek city-states a lot. They made Greeks see a much bigger world. The endless fights between cities, common in earlier centuries, now seemed small. Many young and ambitious Greeks moved to the new Greek empires in the east. They went to Alexandria, Antioch, and other new Hellenistic cities. Some even went as far as modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. There, Greek kingdoms lasted until the late 1st century BC.

The defeat of Greek cities by Philip and Alexander taught Greeks a lesson. Their city-states could no longer be powerful on their own. They realized they could not challenge Macedonia and its new kingdoms unless they united. Greeks loved their local independence too much to fully unite. But they tried to form groups or federations to regain some freedom.

After Alexander died, his generals fought for power. This caused his empire to break into several new kingdoms. Cassander, son of Alexander's top general Antipater, took control of Macedon. After years of fighting, he ruled most of Greece. He built a new Macedonian capital at Thessaloniki and was a good ruler.

Cassander faced a challenge from Antigonus I Monophthalmus, who ruled Anatolia. Antigonus promised to free the Greek cities if they supported him. This led to successful revolts against Cassander's local rulers. In 307 BC, Antigonus's son Demetrius captured Athens. He brought back its democratic system, which Alexander had stopped. But in 301 BC, Cassander and other Hellenistic kings defeated Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus. This ended Antigonus's challenge.

After Cassander died in 298 BC, Demetrius took the Macedonian throne. He gained control of most of Greece. But a second group of Greek rulers defeated him in 285 BC. Control of Greece then went to King Lysimachus of Thrace. Lysimachus was also defeated and killed in 280 BC. The Macedonian throne then passed to Demetrius's son, Antigonus II. He also defeated an invasion of Greek lands by the Gauls, who lived in the Balkans. The fight against the Gauls brought together the Antigonids of Macedon and the Seleucids of Antioch. This alliance was also against the richest Hellenistic power, the Ptolemies of Egypt.

Antigonus II ruled until he died in 239 BC. His family kept the Macedonian throne until the Romans ended it in 146 BC. However, their control over the Greek city-states was not always strong. Other rulers, especially the Ptolemies, paid groups in Greece that were against Macedonia. This helped weaken the Antigonids' power. Antigonus placed soldiers at Corinth, a key city in Greece. But Athens, Rhodes, Pergamum, and other Greek states stayed mostly independent. They formed the Aetolian League to protect their freedom. Sparta also remained independent but usually refused to join any league.

In 267 BC, Ptolemy II convinced the Greek cities to revolt against Antigonus. This became the Chremonidean War, named after the Athenian leader Chremonides. The cities lost, and Athens lost its independence and democratic government. The Aetolian League was limited to the Peloponnese. But after gaining control of Thebes in 245 BC, it became an ally of Macedonia. This marked the end of Athens as a major political player. However, it remained the largest, richest, and most cultured city in Greece. In 255 BC, Antigonus defeated the Egyptian fleet at Cos. He then brought the Aegean islands, except Rhodes, under his rule.

Greek City-States and Leagues

Even with less political power, the Greek city-state, or polis, remained the main way people lived and organized themselves in Greece. Famous city-states like Athens and Ephesus grew and did well during this time. While Greek cities still fought each other, they also worked together. They formed alliances or became allies of strong Hellenistic states. This protected them from attacks by other cities.

The Aetolians and Achaeans created strong federal states called leagues (koinon). These leagues were run by councils of city representatives and meetings of league citizens. At first, these leagues were for people of the same ethnic group. But later, they started to include cities from outside their traditional areas. The Achaean League eventually included almost all of the Peloponnese, except Sparta. The Aetolian League grew into Phocis. During the 3rd century BCE, these leagues could defend themselves against Macedon. The Aetolian league even defeated a Celtic invasion of Greece at Delphi.

After Alexander's death, Antipater defeated Athens in the Lamian War. A Macedonian army was stationed at its port in the Piraeus. To fight the power of Macedon under Cassander, Athens sought alliances with other Hellenistic rulers. For example, Antigonus I Monophthalmus sent his son Demetrius to capture the city in 307 BC. After Demetrius took Macedon, Athens allied with Ptolemaic Egypt. They wanted to gain independence from Demetrius. With Ptolemaic troops, they rebelled and defeated Macedon in 287 BC, though the Piraeus still had Macedonian soldiers. Athens fought more unsuccessful wars against Macedon with Ptolemaic help, like the Chremonidean War. The Ptolemaic kingdom became Athens' main ally, providing soldiers, money, and supplies. Athens honored the Ptolemaic Kingdom in 224/223 BC by naming a new tribe "Ptolemais" and starting a religious group called the Ptolemaia. Hellenistic Athens also saw the rise of new types of plays and famous schools of philosophy like Stoicism and Epicureanism. As the Ptolemaic empire weakened, the Attalids in Pergamon became Athens' supporters and protectors. Athens later also created a religious group for the Pergamene king Attalos I.

Philip V and Rome's Influence

Antigonus II died in 239 BC. After his death, the city-states of the Achaean League revolted again. Their main leader was Aratus of Sicyon. Antigonus's son Demetrius II died in 229 BC. He left a child, Philip V, as king, with general Antigonus Doson as his helper. The Achaeans were technically under Ptolemy, but they were mostly independent. They controlled most of southern Greece. Athens stayed out of this conflict.

Sparta remained against the Achaeans. In 227 BC, Sparta's king Cleomenes III invaded Achaea and took control of the League. Aratus preferred distant Macedon over nearby Sparta. He allied with Doson, who defeated the Spartans in 222 BC and took over their city. This was the first time Sparta had ever been taken by an outside power.

Philip V became king when Doson died in 221 BC. He was the last Macedonian ruler with the skill and chance to unite Greece. He wanted to keep Greece independent from the growing power of Rome. People called him "the darling of Hellas." Under his leadership, the Peace of Naupactus (217 BC) ended fighting between Macedon and the Greek leagues. At this time, he controlled all of Greece except Athens, Rhodes, and Pergamum.

However, in 215 BC, Philip made an alliance with Rome's enemy, Carthage. This brought Rome directly into Greek affairs for the first time. Rome quickly convinced the Achaean cities to leave Philip. They also formed alliances with Rhodes and Pergamum, which was now the strongest power in Asia Minor. The First Macedonian War started in 212 BC and ended without a clear winner in 205 BC. But Macedon was now seen as an enemy of Rome. Rome's ally, Rhodes, gained control of the Aegean islands.

In 202 BC, Rome defeated Carthage. This left Rome free to focus on the east. Their Greek allies, Rhodes and Pergamum, urged them on. In 198 BC, the Second Macedonian War began for unclear reasons. But it was likely because Rome saw Macedon as a possible ally of the Seleucids, the biggest power in the east. Philip's allies in Greece left him. In 197 BC, the Roman leader Titus Quinctius Flamininus decisively defeated him at Cynoscephalae.

Luckily for the Greeks, Flamininus was a fair man and admired Greek culture. Philip had to give up his fleet and become a Roman ally, but he was otherwise spared. At the Isthmian Games in 196 BC, Flamininus declared all the Greek cities free. However, Roman soldiers were placed at Corinth and Chalcis. The freedom Rome promised was not real. All cities except Rhodes joined a new League that Rome controlled. Democracies were replaced by governments run by rich families allied with Rome.

Rome's Growing Power

In 192 BC, war broke out between Rome and the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III. Antiochus invaded Greece with 10,000 soldiers. He was chosen as the main commander of the Aetolians. Some Greek cities now saw Antiochus as their savior from Roman rule. But Macedon joined forces with Rome. In 191 BC, the Romans under Manius Acilius Glabrio defeated Antiochus at Thermopylae. They forced him to leave Asia. During this war, Roman troops entered Asia for the first time. They defeated Antiochus again at Magnesia on the Sipylum (190 BC). Greece now lay on Rome's path to the east, and Roman soldiers became a constant presence. The Peace of Apamaea (188 BC) made Rome the dominant power throughout Greece.

In the years that followed, Rome became more involved in Greek politics. This was because the losing side in any dispute would ask Rome for help. Macedon was still independent, but it was officially a Roman ally. When Philip V died in 179 BC, his son Perseus took over. Like all Macedonian kings, he dreamed of uniting the Greeks under Macedonian rule. Macedon was too weak to do this now. But Rome's ally Eumenes II of Pergamum convinced Rome that Perseus was a threat to Rome's power.

The End of Greek Independence

Because of Eumenes's tricks, Rome declared war on Macedon in 171 BC. They sent 100,000 soldiers into Greece. Macedon was no match for this army. Perseus could not get the other Greek states to help him. Poor leadership by the Romans allowed him to hold out for three years. But in 168 BC, the Romans sent Lucius Aemilius Paullus to Greece. At Pydna, the Macedonians were completely defeated. Perseus was captured and taken to Rome. The Macedonian kingdom was broken into four smaller states. All Greek cities that had helped Macedon, even just by speaking in favor of it, were punished. Even Rome's allies, Rhodes and Pergamum, lost their real independence.

Under a leader named Andriscus, Macedon rebelled against Roman rule in 149 BC. As a result, Rome directly took over Macedon the next year. It became a Roman province, the first Greek state to suffer this fate. Rome then demanded that the Achaean League, the last strong group of Greek independence, be broken up. The Achaeans refused. Feeling they might as well die fighting, they declared war on Rome. Most Greek cities joined the Achaeans. Even slaves were freed to fight for Greek independence. The Roman leader Lucius Mummius marched from Macedonia. He defeated the Greeks at Corinth, which was then completely destroyed.

In 146 BC, the Greek mainland, but not the islands, became a Roman protectorate. Roman taxes were put in place, except in Athens and Sparta. All cities had to accept rule by Rome's local allies. In 133 BC, the last king of Pergamum died and left his kingdom to Rome. This brought most of the Aegean peninsula under direct Roman rule as part of the province of Asia.

Greece's final downfall came in 88 BC. King Mithridates of Pontus rebelled against Rome. He killed up to 100,000 Romans and Roman allies across Asia Minor. Even though Mithridates was not Greek, many Greek cities, including Athens, removed their Roman rulers and joined him. When the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla drove him out of Greece, Rome took revenge on Greece again. The Greek cities never fully recovered. Mithridates was finally defeated by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) in 65 BC.

More damage came to Greece from the Roman civil wars, which were partly fought there. Finally, in 27 BC, Augustus directly added Greece to the new Roman Empire. It became the province of Achaea. The wars with Rome had left some areas of Greece with fewer people and feeling discouraged. However, Roman rule at least brought an end to warfare. Cities like Athens, Corinth, Thessaloniki, and Patras soon became wealthy again.

See also

- Ancient Greek architecture

- Ancient Greek art

- Culture of ancient Greece

- Hellenization