Gauls facts for kids

The Gauls were a group of Celtic people who lived in mainland Europe during the Iron Age and the Roman period. This was roughly from the 5th century BC to the 5th century AD. Their homeland was called Gaul, and they spoke a language called Gaulish.

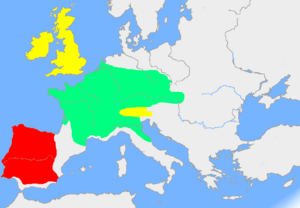

The Gauls first appeared around the 5th century BC. They were known for their La Tène culture north and west of the Alps mountains. By the 4th century BC, they had spread across much of what is now France, Belgium, Switzerland, Southern Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic. They controlled important trade routes along major rivers like the Rhône, Seine, Rhine, and Danube.

Their power reached its peak in the 3rd century BC. During this time, Gauls expanded into Northern Italy (called Cisalpine Gaul by the Romans). This led to wars with the Romans. They also moved into the Balkans, which led to wars with the Greeks. Some of these Gauls eventually settled in Anatolia (modern Turkey). They became known as the Galatians.

After the First Punic War, the growing Roman Republic started to challenge the Gauls. The Battle of Telamon in 225 BC marked the beginning of their decline. The Romans finally conquered Gaul in the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC). Gaul then became a Roman province. This led to a mix of Gallic and Roman ways, creating the Gallo-Roman culture.

The Gauls were made up of many different tribes. Many of these tribes built large, strong settlements called oppida, like Bibracte. They also made their own coins. Gaul was never ruled by one single leader or government. However, Gallic tribes could join forces for big military operations. Famous leaders like Brennus and Vercingetorix led these efforts. The Gauls followed an ancient Celtic religion led by druids. They also created the Coligny calendar.

Contents

Name

The name Galli (Gauls) likely comes from a Celtic word meaning 'power' or 'ability'. Other related names include Galátai and Gallitae. Even the modern French word gaillard (meaning 'brave' or 'strong') comes from a similar root.

Julius Caesar, a Roman leader, wrote in the mid-1st century BC that the Gauls in the area he called Gallia Celtica called themselves Celtae in their own language. The Romans, however, called them Galli.

The English word "Gaul" does not come from the Latin Galli. Instead, it comes from a Germanic word *Walhaz. This word originally referred to the Gallic tribe called Volcae. Over time, it came to mean Celtic and Romance language speakers in medieval Germanic languages. This is also where words like Welsh and Waals come from.

History

Early History and Culture

Gallic culture developed over a long time, starting around 1000 BC. The Urnfield culture (around 1300–750 BC) shows the Celts as a distinct group of Indo-European-speaking people. When people started working with iron, it led to the Hallstatt culture around the 8th century BC. Many believe the Proto-Celtic language was spoken at this time. The Hallstatt culture then changed into the La Tène culture around the 5th century BC.

The Greek and Etruscan civilizations, with their colonies, began to influence the Gauls. This was especially true in the Mediterranean area. Gauls, led by a chief named Brennus, even attacked Rome around 390 BC.

By the 5th century BC, the tribes later known as Gauls had moved from central France to the Mediterranean coast. Gallic invaders settled in the Po Valley in the 4th century BC. They defeated Roman forces under another Brennus in 390 BC. They even raided Italy as far south as Sicily.

In the early 3rd century BC, the Gauls tried to expand eastward into the Balkan peninsula. This area was a Greek province at the time. The Gauls wanted to reach and loot the rich Greek city-states. However, the Greeks defeated most of the Gallic army. The few survivors had to flee.

Many Gauls also served as soldiers for Carthage during the Punic Wars. One of the main rebel leaders in the Mercenary War, Autaritus, was of Gallic origin.

Wars in the Balkans

During their trips into the Balkans, led by chiefs like Cerethrios, Brennos, and Bolgios, the Gauls raided the Greek mainland twice.

After the second trip, the Gallic raiders were pushed back by a combined army of different Greek city-states. They had to retreat to Illyria and Thrace. However, the Greeks allowed the Gauls to pass safely. These Gauls then traveled to Asia Minor and settled in Central Anatolia. This area became known as Galatia.

These Galatians caused a lot of trouble. They were stopped by the Greek Seleucid king Antiochus I in 275 BC. He used war elephants and light-armed soldiers against them. After this, the Galatians worked as hired soldiers (mercenaries) all over the Hellenistic Eastern Mediterranean. This included Ptolemaic Egypt, where they tried to take control of the kingdom under Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 BC).

In their first invasion of Greece (279 BC), the Gauls defeated the Macedonians and killed their king, Ptolemy Keraunos. They then focused on looting the rich Macedonian countryside. They avoided the heavily protected cities. A Macedonian general named Sosthenes gathered an army. He defeated Bolgius and pushed back the Gauls.

In the second Gallic invasion of Greece (278 BC), the Gauls, led by Brennos, suffered heavy losses. They faced a Greek army at Thermopylae. However, with help from people from Heraclea, they found a mountain path around Thermopylae. This allowed them to surround the Greek army, just like the Persian army had done in the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC. This time, they defeated the entire Greek army.

After passing Thermopylae, the Gauls headed for the rich treasury at Delphi. There, they were defeated by the re-formed Greek army. This led to a series of retreats for the Gauls, with huge losses. They were pushed all the way back to Macedonia and then out of the Greek mainland. Most of the Gallic army was defeated. The surviving Gauls were forced to flee from Greece. Their leader, Brennos, was badly hurt at Delphi and died. (This Brennos is not the same leader who attacked Rome a century earlier in 390 BC.)

Galatian War

In 278 BC, Gallic settlers in the Balkans were asked by Nicomedes I of Bithynia to help him in a fight against his brother. There were about 10,000 Gallic fighters and a similar number of women and children. They were divided into three tribes: Trocmi, Tolistobogii, and Tectosages.

They were eventually defeated by the Seleucid king Antiochus I in 275 BC. In this battle, the Seleucid war elephants scared the Galatians. Even though their invasion was stopped, the Galatians were not wiped out. They continued to demand money from the Greek states in Anatolia to avoid war.

Four thousand Galatians were hired as soldiers by the Ptolemaic Egyptian king Ptolemy II Philadelphus in 270 BC. According to a writer named Pausanias, soon after they arrived, the Celts planned "to seize Egypt." So, Ptolemy left them on a deserted island in the Nile River.

Galatians also helped in the victory at Raphia in 217 BC under Ptolemy IV Philopator. They continued to serve as hired soldiers for the Ptolemaic dynasty until it ended in 30 BC. They sided with a rebel Seleucid prince named Antiochus Hierax, who ruled in Asia Minor. Hierax tried to defeat King Attalus I of Pergamum (241–197 BC). Instead, the Greek cities united under Attalus. His armies badly defeated the Galatians at the Battle of the Caecus River in 241 BC.

After this defeat, the Galatians were still a serious threat to the states of Asia Minor. They remained a threat even after their defeat by Gnaeus Manlius Vulso in the Galatian War (189 BC). Galatia's power declined, and sometimes it fell under the control of the Kingdom of Pontus. They were finally freed during the Mithridatic Wars, where they supported Rome. In 64 BC, Galatia became a state that was controlled by the Roman Empire. The old system of government disappeared. Three chiefs were appointed, one for each tribe. But one of these chiefs, Deiotarus, who lived at the same time as Cicero and Julius Caesar, soon took control of the other two areas. The Romans eventually recognized him as the 'king' of Galatia. The Galatian language continued to be spoken in central Anatolia until the 6th century AD.

Roman Wars

In the Second Punic War, the famous Carthaginian general Hannibal used Gallic hired soldiers when he invaded Italy. They helped him win some of his most impressive victories, including the battle of Cannae.

By the 2nd century BC, the Gauls were so successful that the powerful Greek colony of Massilia had to ask the Roman Republic for protection from them. The Romans stepped in southern Gaul in 125 BC. They conquered the area, which later became known as Gallia Narbonensis, by 121 BC.

In 58 BC, Julius Caesar started the Gallic Wars. He conquered all of Gaul by 51 BC. Caesar wrote that the Gauls (who called themselves Celtae) were one of the three main peoples in the area. The others were the Aquitanians and the Belgae. Caesar probably invaded Gaul because he needed gold to pay his debts. He also needed a successful military campaign to boost his political career. The people of Gaul could provide him with both. So much gold was taken from Gaul that after the war, the price of gold dropped by as much as 20%.

The Gauls were brave fighters, just like the Romans. However, they were divided among their many tribes. This made it easier for Caesar to win. Vercingetorix tried to unite the Gauls against the Roman invasion, but it was too late. After Gaul was taken over by Rome, a mixed Gallo-Roman culture began to form.

Roman Gaul

After more than a century of fighting, the Cisalpine Gauls (Gauls in northern Italy) were brought under Roman control in the early 2nd century BC. The Transalpine Gauls (Gauls in France) continued to do well for another century. They joined the Germanic tribes called the Cimbri and Teutones in the Cimbrian War. There, they defeated and killed a Roman consul at Burdigala in 107 BC. Later, they were important among the rebelling gladiators in the Third Servile War.

The Gauls were finally conquered by Julius Caesar in the 50s BC. This happened despite a rebellion led by the Arvernian chief Vercingetorix. During the Roman period, the Gauls became part of the Gallo-Roman culture. They were also influenced by expanding Germanic tribes. During a difficult time for the Roman Empire in the 3rd century AD, a short-lived Gallic Empire was formed by a general named Postumus.

Physical Appearance

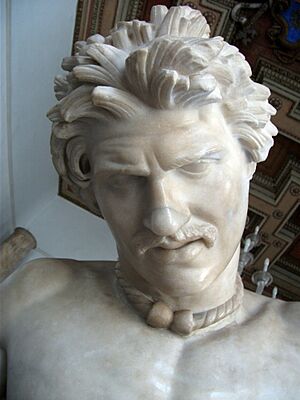

Ancient writers described the Gauls' appearance. A Roman poet named Virgil (who lived in the 1st century BC) wrote that the Gauls had light hair and golden clothes. He said: "Golden is their hair and golden their garb. They are splendid in their striped cloaks and their milk white necks are circled in gold."

A Greek historian named Diodorus Siculus (also 1st century BC) described them as tall and strongly built. He said they had very light skin and light hair. They had long hair and mustaches. He wrote: "The Gauls are tall, with strong muscles, and white skin. Their hair is blond, and they even make it more blond by washing it in limewater. They pull their hair back from their forehead to the top of their head. Some shave their beards, but others let it grow a little. The nobles shave their cheeks but let their mustache grow until it covers their mouth."

Another historian, Jordanes, in his book about the Goths, described the Gauls as light-haired and large-bodied. He compared them to the Caledonians (ancient people of Scotland). This suggests that Gauls were generally seen as having reddish hair and large bodies.

Culture

Archaeologists have found many pre-Roman gold mines all over Gaul (at least 200 in the Pyrenees mountains). This suggests the Gauls were very rich. Large amounts of gold coins and artifacts also prove this. They also had highly developed towns, which Caesar called oppida. Examples include Bibracte, Gergovia, Avaricum, Alesia, and Manching.

Modern archaeology shows that the lands of Gaul were quite advanced and wealthy. Most Gauls traded with Roman merchants. Some tribes, especially those governed by republics like the Aedui and Helvetii, had strong political friendships with Rome. They imported Mediterranean wine in huge amounts. Many wine vessels have been found in digs across Gaul. The largest and most famous is the one found in the Vix Grave, which is 1.63 meters (5 feet 4 inches) tall.

Art

Gallic art is linked to two main archaeological cultures: the Hallstatt culture (around 1200–450 BC) and the La Tène culture (around 450–1 BC). Each period has its own style, but they also share many features. From the late Hallstatt period and throughout the La Tène period, Gallic art is considered the beginning of what we now call Celtic art. After the end of La Tène and the start of Roman rule, Gallic art changed into Gallo-Roman art.

Hallstatt art mostly used geometric shapes and lines. This can be seen on beautiful metal objects found in graves. Animals, especially waterfowl, were often part of the designs, more so than humans. Common finds include weapons, often with handles shaped like curving forks. Jewelry included brooches (often with disks hanging on chains), armlets, and some torcs (neck rings). Most of these were made of bronze, but some, likely for chiefs, were made of gold. Decorated buckets (situlae) and bronze belt plates show influence from Greek and Etruscan art. Many of these features continued into the La Tène style.

La Tène metalwork used bronze, iron, and gold. It developed from the Hallstatt culture. Its style is known for "classical plant and leaf designs like palmettes, vines, tendrils, and lotus flowers, along with spirals, S-scrolls, lyre, and trumpet shapes." These designs can be found on fine bronze vessels, helmets, shields, horse gear, and fancy jewelry, especially torcs and fibulae. Early on, La Tène style took designs from other cultures and made them into something new and unique. Influences came from Scythian art, as well as Greek and Etruscan art.

-

Agris Helmet. Found in Agris, Charente, France, 350 BC

-

A 24-karat Celtic "torc", found in the grave of the "Lady of Vix", Burgundy, France, 480 BC

-

A belt made of 2.8 kg (6.2 lb) of pure gold, found in Guînes, France, 1200–1000 BC

-

Celtic gold bracelet found in Cantal, France

-

Celtic helmet decorated with gold "triskeles", found in Amfreville-sous-les-Monts, France, 400 BC

-

Celtic war trumpet called "carnyx" found in the Gallic sanctuary of Tintignac, Corrèze, France.

-

The Vix krater, found in the grave of the "Lady of Vix", in northern Burgundy, France, 500 BC

-

Gaul, Armorica coin showing stylized head and horse (Jersey moon head style, c. 100–50 BC)

Social Structure

Gallic society was largely led by the druids, who were priests. But druids were not the only powerful group. The early political system was complex. The basic unit of Gallic politics was the tribe. Each tribe had a council of elders, and at first, a king. Later, a magistrate was elected each year to lead. For example, the Aedui tribe had a leader called a "Vergobret". This position was like a king, but its powers were limited by rules set by the council.

The tribal groups, or pagi as the Romans called them, were organized into larger groups called civitates. The Romans later used these groupings for their local control system. These civitates also became the basis for France's church areas (bishoprics and dioceses). These stayed mostly the same until the French Revolution created the modern department system.

Even though tribes were somewhat stable, Gaul as a whole was often politically divided. There was almost no unity among the different tribes. Only during very difficult times, like when Caesar invaded, could the Gauls unite under one leader like Vercingetorix. Even then, disagreements among groups were clear.

The Romans generally divided Gaul into Provincia (the conquered area around the Mediterranean) and the northern Gallia Comata ("free Gaul" or "wooded Gaul"). Caesar divided the people of Gallia Comata into three main groups: the Aquitani, the Galli (who called themselves Celtae), and the Belgae. In modern terms, Gallic tribes are defined by speaking Gaulish. The Aquitani were probably Vascons, while the Belgae would likely be considered Gallic tribes, perhaps with some Germanic influences.

Julius Caesar, in his book Commentarii de Bello Gallico, wrote: "All Gaul is divided into three parts. The Belgae live in one, the Aquitani in another, and those who call themselves Celts (and we call Gauls) live in the third. All these groups are different in language, customs, and laws. The Garonne river separates the Gauls from the Aquitani. The Marne and Seine rivers separate them from the Belgae. Of all these, the Belgae are the bravest. This is because they are furthest from our Roman way of life and culture. Merchants visit them less often, bringing fewer things that make people weak. They are also closest to the Germani, who live beyond the Rhine, and they are always at war with them. For this reason, the Helvetii also are braver than the rest of the Gauls. They fight the Germani almost daily, either pushing them out of their own lands or fighting on their borders. The part that the Gauls live in starts at the Rhône river. It is bordered by the Garonne river, the Atlantic Ocean, and the lands of the Belgae. It also borders the Sequani and Helvetii, near the Rhine river, and stretches north. The Belgae's land starts at the very edge of Gaul and goes to the lower part of the Rhine river. It faces north and the rising sun. Aquitania stretches from the Garonne to the Pyrenees mountains and to the part of the Atlantic (Bay of Biscay) near Spain. It faces between the setting sun and the north star."

Language

Gaulish, or Gallic, was the Celtic language spoken in Gaul before Latin became dominant. According to Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic War, it was one of three languages in Gaul. The others were Aquitanian and Belgic. In Gallia Transalpina, which was a Roman province by Caesar's time, Latin had been spoken for at least a century. Gaulish is grouped with other ancient Celtic languages like Celtiberian, Lepontic, and Galatian. Lepontic and Galatian are sometimes thought of as dialects of Gaulish.

We don't know exactly when Gaulish stopped being spoken, but it's thought to be around the middle of the 1st millennium AD. It might have survived in some parts of France until the mid to late 6th century. Even though Roman culture greatly influenced the Gauls, the Gaulish language seems to have survived. It was spoken alongside Latin during the centuries of Roman rule in Gaul.

Gaulish also helped shape the everyday Latin spoken in Gaul, which later developed into French. It influenced French with borrowed words, copied phrases, and even changes in sounds, verb forms, and word order. Recent computer studies suggest that Gaulish played a role in how the gender of words changed in early French. Words often shifted to match the gender of the related Gaulish word with the same meaning.

Religion

Like other Celtic peoples, the Gauls had a polytheistic religion, meaning they worshipped many gods. We learn about their religion from archaeological finds and writings by Greeks and Romans.

Some gods were worshipped only in one area, but others were known more widely. The Gauls seem to have had a father god, who was often a god of the tribe and of the dead (Toutatis was likely one name for him). They also had a mother goddess, linked to the land, earth, and fertility (Matrona was probably one name for her). The mother goddess could also be a war goddess, protecting her tribe and its land.

There also seems to have been a male sky god, identified with Taranis. He was linked to thunder, the wheel, and the bull. There were gods of skill and craft, like the widely known god Lugus, and the smith god Gobannos. Gallic healing gods were often connected to sacred springs, such as Sirona and Borvo. Other gods worshipped across different regions included the horned god Cernunnos, the horse and fertility goddess Epona, Ogmios, Sucellos, and his partner Nantosuelta. Caesar said the Gauls believed they all came from a god of the dead and underworld, whom he compared to Dīs Pater. Some gods were seen as three-in-one, like the Three Mothers. According to Miranda Aldhouse-Green, the Celts were also animists, believing that every part of the natural world had a spirit.

Greek and Roman writers said the Gauls believed in reincarnation. Diodorus said they believed souls were reborn after a certain number of years, probably after spending time in an afterlife. He noted they buried grave goods (items) with the dead.

Gallic religious ceremonies were led by priests called druids. Druids also acted as judges, teachers, and keepers of ancient knowledge. There is evidence that the Gauls sacrificed animals, almost always livestock. An example is the sanctuary at Gournay-sur-Aronde. It seems some animals were given entirely to the gods (by burying or burning them), while others were shared between gods and humans (part eaten and part offered).

The Romans said the Gauls held ceremonies in sacred groves and other natural shrines, called nemetons. Celtic peoples often made votive offerings: valuable items placed in water and wetlands, or in ritual shafts and wells. They often did this in the same place for many generations.

After the Roman conquest, a mixed syncretic Gallo-Roman religion developed. It combined Roman and Gallic gods, such as Lenus Mars, Apollo Grannus, and the pairing of Rosmerta with Mercury.

List of Gaulish tribes

The Gauls were made up of many tribes. Each tribe controlled a specific area and often built large, fortified settlements called oppida. After conquering Gaul, the Roman Empire turned most of these tribes into civitates (administrative districts). The early church in Gaul then based its geographical divisions on these, and they continued as French dioceses until the French Revolution.

Below is a list of recorded Gallic tribes, with their names in Latin and their reconstructed Gaulish names (marked with *), as well as their main towns during the Roman period.

| Tribe | Capital |

|---|---|

| Aedui | Bibracte (Mont Beuvray) |

| Allobroges | Solonion (Salagnon); Vienna (Vienne) |

| Ambarri | near junction of Rhône & Saône rivers |

| Ambiani | Samarobriva (Amiens) |

| Andecavi (*Andecawī) | Juliomagos Andecavorum (Angers) |

| Arecomici | Nemausus (Nîmes) |

| Arverni (*Arwernī) | Gergovia (La Roche-Blanche) |

| Atrebates | Nemetocenna (Arras) |

| Aulerci Cenomani | Vindunom (Le Mans) |

| Bodiocasses | Augustodurum (Bayeux) |

| Boii | Bononia (Bologna) |

| Bellovaci (*Bellowacī) | Bratuspantion (Beauvais) |

| Bituriges Cubi | Avaricum (Bourges) |

| Bituriges Vivisci | Burdigala (Bordeaux) |

| Brannovices (*Brannowīcēs) | Matiscon (Mâcon) |

| Brigantii | Brigantion (Bregenz) |

| Cadurci | Uxellodunum (Cahors) |

| Caleti | Caracotinum (Harfleur); Sandouville?; Lillebonne? |

| Carni | Aquileia |

| Carnutes (*Carnūtī) | Autricum (Chartres); Cenabum (Orléans) |

| Catalauni (*Catu-wellaunī) | Durocatelaunos (Châlons-en-Champagne) |

| Caturiges | Ebrodunom (Embrun) |

| Cavari (*Cawarī) | Arausion (Orange) |

| Cenomani | Brixia (Brescia) |

| Ceutrones | Darantasia (Tarentaise/Moûtiers) |

| Coriosolites | Corseul |

| Diablintes | Noeodunom (Jublains) |

| Durocasses | Durocassium (Dreux) |

| Eburones | Atuatuca (Tongeren) |

| Eburovices (*Eburowīcēs) | Mediolanum Aulercorum (Évreux) |

| Gabali | Andreritum (Javols) |

| Graioceli | Ocellum (Aussois)? |

| Helvetii (*Heluetī) | Brenodurum? (Bern, Switzerland); Aventicum (Avenches) |

| Helvii (*Helwī) | Alba Helviorum (Alba-la-Romaine) |

| Insubres | Mediolanom (Milan) |

| Lemovices (*Lemowīcēs) | Durotincum (Villejoubert); Augustoritum (Limoges) |

| Leuci (*Lewcī) | Tullum (Toul) |

| Lexovii (*Lexsowī) | Noviomagos (Lisieux) |

| Lingones | Andematunnon (Langres) |

| Mediomatrici | Divodurum (Metz) |

| Medulli | Moriana? |

| Menapii | Castellum Menapiorum (Cassel) |

| Morini | Bononia (Boulogne-sur-Mer) |

| Namnetes | Condevincum (Nantes) |

| Nantuates | Tarnaiae (Massongex) |

| Nervii (*Nerwī) | Bagacum (Bavay) |

| Nitiobroges | Aginnon (Agen) |

| Osismii (*Ostimī) | Vorgium (Carhaix) |

| Parisii | Lutetia (Paris) |

| Petrocorii | Vesunna (Périgueux) |

| Pictones | Lemonum (Poitiers) |

| Rauraci | Basel oppidum; Augusta Raurica (Kaiseraugst) |

| Redones | Condate (Rennes) |

| Remi | Durocortorum (Reims) |

| Ruteni | Segodunom (Rodez) |

| Salassi | Aosta |

| Santoni | Mediolanum Santonum (Saintes) |

| Seduni | Sedunum (Sion, Switzerland) |

| Segusiavi (*Segusiawī) | Forum Segusiavorum (Feurs) |

| Segusini | Segusio (Susa) |

| Senoni | Agedincum (Sens) |

| Sequani | Vesontion (Besançon) |

| Suessiones | Noviodunum (Pommiers); Augusta Suessionum (Soissons) |

| Taurini | Taurasia (Turin) |

| Tectosagii | Tolosa (Toulouse) |

| Tigurini | Eburdodunom? (Yverdon) |

| Treveri (*Trēwerī) | Trier; Titelberg |

| Tricastini | Augusta Tricastinorum (Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux) |

| Turoni | Ambatia (Amboise); Caesarodunum (Tours) |

| Velaunii (*Wellaunī) | Brigantio (Briançonnet)? |

| Veliocasses (*Weliocassēs) | Rotomagos (Rouen) |

| Vellavi (*Wellawī) | Ruessium (Saint-Paulien); Anicium (Le Puy-en-Velay) |

| Venelli (*Wenellī) | Crociatonum (Carentan) |

| Veneti (*Wenetī) | Dariorium (Vannes) |

| Veragri (*Weragrī) | Octodurus (Martigny) |

| Vertamocorii (*Wertamocorī) | Novaria (Novara) |

| Viducasses (*Widucassēs) | Aregenua (Vieux) |

| Vindelici (*Windelicī) | Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg) |

| Viromandui (*Wiromanduī) | Augusta Viromanduorum (Saint-Quentin, Aisne) |

| Vocontii (*Wocontī) | Vaison-la-Romaine |

Genetics

Recent genetic studies have looked at the DNA of ancient Gauls. A study from December 2018 examined 45 people buried at a La Tène cemetery in France. These people were identified as Gauls. Their DNA showed they had a lot of "steppe ancestry" (from an area near modern Ukraine and southwestern Russia). They were also closely related to people from the earlier Bell Beaker culture. This suggests that people in France from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age were genetically connected. The study also found significant gene flow with Great Britain and Iberia (Spain and Portugal). The results partly support the idea that French people are largely descended from the Gauls.

Another study from October 2019 looked at the DNA of 43 mothers and 17 fathers from the same cemetery. It also looked at 27 mothers and 19 fathers from another La Tène burial site near modern Paris. These ancient Gauls looked genetically similar to people from earlier Yamnaya, Corded Ware, and Bell Beaker cultures. They had many different maternal lineages (DNA passed down from mothers) linked to steppe ancestry. However, all the paternal lineages (DNA passed down from fathers) belonged to a specific group called haplogroup R1b, which is also linked to steppe ancestry. This suggests that the Gauls of the La Tène culture passed down their family lines through the father's side and that men tended to stay in their local area. This matches what archaeologists and ancient writers have found.

A study published in April 2022 examined 49 genomes from 27 sites in Bronze Age and Iron Age France. The study found strong genetic continuity between these two periods, especially in southern France. The samples from northern and southern France were very similar. Northern samples showed links to people from Great Britain and Sweden at that time. Southern samples showed links to Celtiberians (Celts in Spain). The northern French samples had more steppe-related ancestry than the southern ones. R1b was by far the most common paternal lineage, and H was the most common maternal lineage. The Iron Age samples looked like modern-day populations in France, Great Britain, and Spain. This evidence suggests that the Gauls of the La Tène culture mostly developed from the local Bronze Age populations.

See also

In Spanish: Galos (pueblo) para niños

In Spanish: Galos (pueblo) para niños

- List of Celtic tribes

- Gallo-Roman enclosure of Le Mans

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |