Gallic Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Gallic Wars |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vercingetorix Throws Down His Arms at the Feet of Julius Caesar, 1899, by Lionel Noel Royer |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Modern estimates:

|

Modern estimates:

|

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

40,000+(Credible estimate)

|

All contemporary numbers are considered not credible by Henige |

||||||||

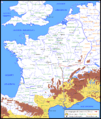

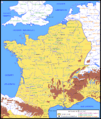

The Gallic Wars were a series of battles fought between 58 and 50 BC. The Roman general Julius Caesar led the Roman army against the peoples of Gaul. Gaul is an ancient region that includes modern-day France, Belgium, and parts of Germany and Switzerland.

Gallic, Germanic, and British tribes fought to protect their homes. The wars ended with the important Battle of Alesia in 52 BC. Rome won completely, taking control of all Gaul. The Gallic tribes were strong fighters, but they were not united. This made it easier for Caesar to win. The Gallic leader Vercingetorix tried to unite them, but it was too late.

Caesar said he was fighting to protect Rome. However, historians believe he fought mostly to become more powerful and pay off his debts. Gaul was important to Rome because tribes from the region had attacked Rome many times. By conquering Gaul, Rome secured its border along the Rhine river.

The wars started in 58 BC when the Helvetii tribe began to migrate. This event drew in other tribes and the Germanic Suebi. By 57 BC, Caesar decided to conquer all of Gaul. He led campaigns in the east, where the Nervii almost defeated him. In 56 BC, Caesar won a naval battle against the Veneti. This gave Rome control of most of northwest Gaul.

In 55 BC, Caesar wanted to boost his public image. He led expeditions across the Rhine river and the English Channel. Rome celebrated Caesar as a hero after his return from Britain. The next year, he returned to Britain with a larger army and conquered much of it. Tribes on the continent rebelled, and the Romans suffered a big defeat. In 53 BC, Caesar launched a harsh campaign to restore order. This failed, and Vercingetorix led a major revolt in 52 BC. Gallic forces won a victory at the Battle of Gergovia. But the Romans' strong siege works at the Battle of Alesia crushed the Gallic forces.

In 51 and 50 BC, there was little fighting. Caesar's troops mostly finished securing Gaul. Gaul was conquered, but it became a Roman province later, in 27 BC. Resistance continued until 70 AD. The war ended when Caesar's troops left Gaul in 50 BC. This was because the Roman Civil War was about to begin. Caesar's success in Gaul made him rich and famous. The Gallic Wars helped Caesar win the Civil War and become dictator. This led to the end of the Roman Republic and the start of the Roman Empire.

Julius Caesar wrote about the Gallic Wars in his book Commentarii de Bello Gallico. This book is the main source of information about the conflict. However, modern historians think Caesar exaggerated some parts. For example, he claimed to have killed over a million Gauls. He also claimed almost no Roman soldiers died. Historians believe Gallic forces were smaller than Caesar said. They also think the Romans suffered more losses than he admitted.

Contents

- Understanding the Gallic Wars

- Beginning the Wars: Campaign Against the Helvetii (58 BC)

- Campaigns in the East (57 BC)

- Campaign Against the Veneti (56 BC)

- Crossing the Rhine and English Channel (55 BC)

- Invading Britain and Unrest in Gaul (54 BC)

- Suppressing Unrest (53 BC)

- Vercingetorix's Revolt (52 BC)

- Pacification of the Last Gauls (51 and 50 BC)

- Sources and History

- In Literature

- Images for kids

- See also

Understanding the Gallic Wars

Life in Gaul before the Wars

The tribes of Gaul were advanced and wealthy. Many traded with Roman merchants. Some, like the Aedui, had good relationships with Rome. By the first century BC, parts of Gaul were becoming urbanized. This meant more wealth and people gathered in cities. This made it easier for Rome to conquer them.

Romans thought the Gauls were "barbarians." However, Gallic cities were similar to those in the Mediterranean. They made coins and traded a lot with Rome. They sold iron, grain, and many slaves. In return, Gauls became rich and enjoyed Roman wine. Romans knew Gauls were strong fighters. They thought some "barbaric" tribes were the fiercest. This was because they were not changed by Roman luxuries.

Roman and Gallic Military Styles

The Gauls and Romans had very different ways of fighting. The Roman army was a professional army. Soldiers were paid and equipped by the state. They were very disciplined and always ready for battle. Roman armies mainly used heavy infantry. They also had auxiliary units from their allies, including some Gauls.

The Gauls were less organized. Each Gallic warrior bought their own gear. Rich Gauls had good equipment, like Roman soldiers. But the average Gallic warrior was not as well-equipped. However, Gauls were a warrior culture. They valued bravery and individual courage. They often raided neighboring tribes, which kept their fighting skills sharp.

Compared to Romans, Gauls used longer swords. They also had much better cavalry. Gauls were generally taller than Romans. This, with their longer swords, gave them an advantage in close combat. Both sides used archers and slingers. Gallic battle strategies varied by tribe. They often fought in open battles to show bravery. Some tribes avoided direct fights with the powerful Romans. They often used attrition warfare, trying to wear down the Romans.

Roman Army Organization

The Gallic Wars confirmed the Roman use of the cohort. This unit was created by the Marian reforms, led by Gaius Marius. A cohort replaced the smaller maniple unit. Cohorts were better for fighting Gallic and Germanic tactics.

Cohorts combined men from different social classes. Rich and poor fought together in one unit. This greatly improved morale. A cohort had 480 men. Ten cohorts, plus cavalry, engineers, and officers, formed a legion. A legion had about 5,000 men.

The Marian reforms also changed how the army's baggage train worked. Each soldier had to carry much of his own gear. This included weapons and enough food for a few days. This reduced the size of the baggage train. It allowed legions to march ahead of their supplies. Still, a legion usually had about a thousand animals. These animals carried tents, siege equipment, and extra food. They also carried tools, records, and personal items.

On the march, a legion with its train stretched for about 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles). Such a large number of animals needed a lot of grass or food. This limited campaigning to times when supplies were available. The challenges of the baggage train often affected Roman decisions during the wars.

Rome's Past Fears

The Romans respected and feared the Gallic tribes. In 390 BC, the Gauls had attacked and looted Rome. This event left a lasting fear of barbarian conquest. In 121 BC, Rome conquered some southern Gauls. They established the province of Transalpine Gaul there.

Just 50 years before the Gallic Wars, in 109 BC, Italy was invaded from the north. Gaius Marius saved Rome after several costly battles. Around 63 BC, a Roman ally, the Gallic Aedui, was attacked. The Gallic Arverni and Sequani tribes, with the Germanic Suebi, attacked them. Rome did not intervene. The Sequani and Arverni defeated the Aedui in 63 BC.

Julius Caesar's Rise to Power

Julius Caesar was a rising politician and general. He was the main Roman leader in the war. As consul (the highest office in Rome) in 59 BC, Caesar had many debts. To strengthen Rome's position, he paid money to Ariovistus, king of the Suebi, for an alliance.

Through his influence, Caesar secured his assignment as proconsul (governor) of two provinces. These were Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum. When the governor of Transalpine Gaul died, that province was also given to Caesar. He was given a five-year term as proconsul. This was longer than the usual one-year term. It allowed him to lead military campaigns without fear of being replaced.

Caesar started with four experienced legions: Legio VII, Legio VIII, Legio IX, and Legio X. He knew most of these legions personally from previous campaigns. He also had the power to recruit more legions and auxiliary units. The province in Northern Italy was useful for his goals. It had many Roman citizens who could join the army.

Caesar wanted to conquer and take wealth from new lands to pay off his debts. Gaul might not have been his first target. He might have planned to attack the Kingdom of Dacia in the Balkans. However, a large migration of Gallic tribes in 58 BC gave him a reason to start a war.

Beginning the Wars: Campaign Against the Helvetii (58 BC)

The Helvetii were a group of five Gallic tribes living in Switzerland. They were surrounded by mountains and rivers. They faced growing pressure from Germanic tribes. Around 61 BC, they planned to move across Gaul to northern Italy. This route would take them through lands of the Aedui (a Roman ally) and Roman Transalpine Gaul.

As news of their migration spread, neighboring tribes worried. Rome sent messengers to convince tribes not to join the Helvetii. Rome also worried that Germanic tribes would move into the lands left empty by the Helvetii. Romans preferred Gauls as neighbors over Germanic tribes.

On March 28, 58 BC, the Helvetii began their journey. They brought all their people and animals. They burned their villages to prevent turning back. When they reached Transalpine Gaul, where Caesar was governor, they asked to cross Roman lands. Caesar considered their request but said no. The Gauls then turned north, avoiding Roman lands entirely.

The threat to Rome seemed over. But Caesar led his army across the border and attacked the Helvetii without being provoked. Historians describe this as an aggressive war by a general seeking to advance his career.

Caesar's delay in answering the Gauls was a tactic. He was in Rome when he heard the news. He rushed to Transalpine Gaul, gathering two legions and auxiliaries. After refusing the Gauls, he returned to Italy to get more legions. Caesar now had between 24,000 and 30,000 legionary troops. He also had many auxiliaries, some of whom were Gauls.

He marched north to the Saône river. He caught the Helvetii in the middle of crossing. He killed those who had not yet crossed. Caesar then crossed the river in one day using a pontoon bridge. He followed the Helvetii but waited for the right moment to attack. The Gauls tried to negotiate, but Caesar's terms were very harsh.

On June 20, Caesar's supplies ran low. This forced him to move towards allied territory in Bibracte. His army had crossed the Saône easily, but his supply train had not. The Helvetii, now joined by Boii and Tulingi allies, attacked Caesar's rear guard.

Battle of Bibracte

In the Battle of Bibracte, Gauls and Romans fought for most of the day. After a tough fight, the Romans won. Caesar placed his legions on a hill slope, which put the Gauls at a disadvantage. The Helvetii started with a possible fake attack, which the Romans easily pushed back.

However, the Boii and Tulingi outmaneuvered the Romans. They attacked their right side. The Romans were surrounded. A fierce battle followed. The soldiers in the last line of the legion were ordered to turn around. They now fought on two sides instead of being attacked from behind. This was a smart tactical decision.

Eventually, the Helvetii were defeated and fled. The Romans chased the outnumbered Boii and Tulingi back to their camps. They killed the fighters, women, and children.

Caesar's army rested for three days to care for the wounded. Then they chased the Helvetii, who surrendered. Caesar ordered them back to their lands. This created a buffer zone between Rome and the more feared Germanic tribes. Caesar claimed a census found in the Helvetian camp showed 368,000 Helvetii. Of these, 92,000 were able-bodied men. Only 110,000 survivors returned home. Historians believe the total was likely between 20,000 and 50,000. Caesar likely exaggerated the numbers for propaganda.

Bibracte, a trading center for the Aedui tribe, was important again in 52 BC. Vercingetorix met other Gallic leaders there to plan his rebellion. After Vercingetorix's revolt failed, Bibracte was slowly abandoned.

Campaign Against the Suebi

Caesar then turned to the Germanic Suebi. He wanted to conquer them too. The Roman Senate had called Ariovistus, king of the Suebi, a "friend and ally of the Roman people." So, Caesar needed a good reason to attack them. He found his excuse after defeating the Helvetii.

A group of Gallic tribes congratulated Caesar. They wanted to meet in a general assembly. They hoped to use the Romans against other Gauls. Diviciacus, leader of the Aedui, spoke for the Gauls. He worried about Ariovistus's conquests and the hostages he had taken. Caesar felt he had to protect the Aedui, who were long-time Roman allies. This also gave him a chance to expand Rome's borders.

When the Harudes (a Suebi ally) attacked the Aedui, Caesar had his reason. Also, a report said a hundred Suebi clans were trying to cross the Rhine into Gaul. Caesar now had the justification he needed to wage war against Ariovistus in 58 BC.

Caesar learned that Ariovistus planned to seize Vesontio, a large Sequani town. Caesar marched there and arrived first. Ariovistus sent messengers to Caesar asking for a meeting. They met under a truce outside town. The truce was broken when Germanic horsemen threw stones at Caesar's escort.

Two days later, Ariovistus asked for another meeting. Caesar sent his trusted friend, Valerius Procillus, and a merchant, Caius Mettius. Ariovistus was insulted and chained the envoys. Ariovistus marched for two days. He camped 2 miles (3.2 km) behind Caesar. This cut off Caesar's supplies and communication.

Caesar could not get Ariovistus to fight. So, Caesar ordered a second, smaller camp built near Ariovistus. The next morning, Caesar lined up his allied troops in front of the second camp. He advanced his legions towards Ariovistus. Each of Caesar's five legates and his quaestor commanded a legion. Caesar lined up on the right side. Ariovistus countered with his seven tribal formations.

Caesar won the battle. This was largely due to a charge by Publius Crassus, son of Marcus Crassus. When the Germanic tribes pushed back the Roman left side, Crassus led his cavalry. He restored balance and ordered the third line of cohorts forward. The entire Germanic line broke and fled. Caesar claimed most of Ariovistus's 120,000 men were killed. Ariovistus and his remaining troops escaped across the Rhine. They never fought Rome again. The Suebi near the Rhine went home. Caesar was victorious. In one year, he had defeated two of Rome's most feared enemies. After this busy year, he returned to Transalpine Gaul. He likely decided then to conquer all of Gaul.

Campaigns in the East (57 BC)

Caesar's victories in 58 BC worried the Gallic tribes. Many knew Caesar would try to conquer all of Gaul. Some sought alliances with Rome. In 57 BC, both sides recruited new soldiers. Caesar started with two more legions than the year before. He had 32,000 to 40,000 men, plus auxiliaries. The number of Gallic fighters is unknown, but Caesar claimed he would fight 200,000.

Caesar again stepped into a Gallic conflict. He marched against the Belgae tribes, who lived in modern-day Belgium. They had attacked a Roman allied tribe. Before marching, Caesar ordered the Remi and other Gauls to investigate the Belgae. The Belgae and Romans met near Bibrax. The Belgae tried to take the fortified oppidum (main settlement) from the Remi. They failed and raided the countryside instead.

Both sides tried to avoid battle. They were both low on supplies. Caesar often took risks and left his baggage train behind. Caesar ordered fortifications built. The Belgae knew this would put them at a disadvantage. Instead of fighting, the Belgic army simply broke up. They knew they could easily re-assemble later.

Caesar saw an opportunity. If he could beat the men home, he could take their lands easily. His army's speed was key to his victories. He rushed to the Belgic Suessiones' oppidum at Villeneuve-Saint-Germain. He laid siege to it. The Belgic army got back into the city secretly at night. But Roman siege preparations were too strong. The Gauls were not used to grand Roman siege warfare. The power of Roman preparations made the Gauls surrender quickly.

This had a ripple effect. The nearby Bellovaci and Ambiones surrendered right after. They saw that the Romans had defeated a powerful army without a fight. But not all tribes were so easily scared. The Nervii allied with the Atrebates and Viromandui. They planned to ambush the Romans. The battle of the Sabis was almost a humiliating defeat for Caesar. The Roman victory was very hard-won.

Nervii Ambush: Battle of the Sabis

The Nervii set up an ambush along the Sambre river. They waited for the Romans, who arrived and began setting up camp. The Romans detected the Nervii. The battle began with Romans sending light cavalry and infantry across the river. Their goal was to keep the Nervii busy while the main force fortified its camp. The Nervii easily pushed back this attack.

Caesar made a serious mistake. He did not set up infantry to protect the camp-building force. The Nervii took advantage of this. Their entire force crossed the river quickly. They caught the Romans by surprise and unprepared. When the battle began, two legions had not even arrived. The Nervii had at least 60,000 fighters. The reserve legions were 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) back with the 8,000 animals of the baggage train. However, soldiers could fight without the train, so the front legions were ready.

The Romans' strong discipline and experience helped them. They quickly formed battle lines. Their center and left sides were successful. They chased the Atrebates across the river. This exposed the half-built camp, and the tribes easily took it. To make things worse for the Romans, their right side was in serious trouble. It had been outflanked. The battle line was too tight to swing a sword. Many officers were dead.

The situation was so bad that Caesar took up his shield. He joined the front line of the legion. His presence greatly boosted morale. He ordered his men to form a defensive square. This opened their ranks and protected them from all sides. What changed the battle was Caesar's reinforcements. The X legion returned from chasing the Atrebates. The two lagging legions finally arrived. The strong stand by the X legion and the timely arrival of help allowed Caesar to regroup. He redeployed his forces and eventually pushed back the Nervii.

Caesar's overconfidence almost led to defeat. But the legions' experience and his personal role in combat turned disaster into a great victory. The Belgae were broken. Most Germanic tribes surrendered to Rome. By the end of the campaigning season, Caesar had conquered tribes along the Atlantic coast. He also dealt with the Atuatuci. They were allies of the Nervii but had broken surrender terms. Caesar punished the Atuatuci by selling 53,000 of them into slavery. By law, the profits were Caesar's.

He faced a small setback in winter. He sent one of his officers to the Great St Bernard Pass. Local tribes fought fiercely, and he stopped that campaign. But overall, Caesar had huge success in 57 BC. He gained great wealth to pay his debts. His reputation grew to heroic levels. When he returned, the Senate gave him an unprecedented 15-day thanksgiving. His political power was now very strong. Again, he returned to Transalpine Gaul for the winter. He wintered his troops in northern Gaul. The tribes there were forced to house and feed them.

Campaign Against the Veneti (56 BC)

The Gauls were angry about feeding Roman troops all winter. Romans sent officers to get grain from the Veneti. This was a group of tribes in northwest Gaul. But the Veneti captured the officers. This was a planned move. They knew it would anger Rome. They prepared by allying with tribes of Armorica. They fortified their hill settlements and prepared a fleet.

The Veneti and other Atlantic coast peoples were skilled sailors. They had ships for the rough Atlantic waters. Romans were not ready for open ocean naval warfare. The Veneti also had sails, while Romans used oars. Rome was a strong naval power in the Mediterranean. But those waters were calm, and ships could be less sturdy. Still, Romans knew they needed a fleet to defeat the Veneti. Many Venetic settlements were isolated and best reached by sea. Decimus Brutus was made commander of the fleet.

Caesar wanted to sail as soon as the weather allowed. He ordered new boats built. He recruited oarsmen from conquered Gaulish regions. This ensured the fleet would be ready quickly. Legions were sent by land, but not as one unit. This suggests Gaul was not as peaceful as Caesar claimed. The legions were likely sent to prevent rebellions.

A cavalry force was sent to control Germanic and Belgic tribes. Troops under Publius Crassus went to Aquitania. Quintus Titurius Sabinus took forces to Normandy. Caesar led the remaining four legions overland. He met his new fleet near the mouth of the Loire river.

The Veneti had the advantage for much of the campaign. Their ships were good for the region. When their hill forts were under siege, they could escape by sea. The less sturdy Roman fleet was stuck in harbor for much of the time. Despite having a superior army and great siege equipment, the Romans made little progress. Caesar realized the campaign could not be won on land. He stopped until the seas calmed enough for Roman ships to be useful.

Battle of Morbihan

Finally, the Roman fleet sailed. It met the Venetic fleet off the coast of Brittany in the Gulf of Morbihan. They fought a battle that lasted from morning until sunset. On paper, the Veneti seemed to have the better fleet. Their ships were made of strong oak beams. This meant they were safe from ramming. Their high sides protected their crews from projectiles. The Veneti had about 220 ships. Caesar did not report the number of Roman ships.

The Romans had one advantage: grappling hooks. These allowed them to tear the sails and rigging of Venetic ships that came close. This made them unable to move. The hooks also let Romans pull ships close enough to board. The Veneti realized the grappling hooks were a huge threat. They tried to retreat. However, the wind dropped. The Roman fleet, which did not rely on sails, caught up. The Romans could now use their superior soldiers to board ships in large numbers. They easily overwhelmed the Gauls. Just as Romans beat Carthage in the First Punic War using the corvus boarding device, a simple tool—the grappling hook—helped them defeat the stronger Venetic fleet.

The Veneti, now without a navy, were defeated. They surrendered. Caesar made an example of the tribal elders by executing them. He sold the rest of the Veneti into slavery. Caesar then turned his attention to the Morini and Menapii tribes along the coast.

Caesar's Commanders and Cleanup Operations

During the Venetic campaign, Caesar's officers were busy. They were securing Normandy and Aquitania. A group of Lexovii, Coriosolites, and Venelli attacked Sabinus. He was entrenched on a hill. This was a bad move by the tribes. By the time they reached the top, they were tired. Sabinus easily defeated them. The tribes surrendered, giving all of Normandy to the Romans.

Crassus had a harder time in Aquitania. With only one legion and some cavalry, he was outnumbered. He raised more forces from Provence. He marched south to what is now the border of Spain and France. Along the way, he fought off the Sotiates. They attacked while the Romans were marching. Defeating the Vocates and Tarusates was tougher. These tribes had allied with a rebel Roman general before. They knew Roman combat and guerrilla tactics. They avoided direct battle and attacked supply lines.

Crassus realized he had to force a battle. He found the Gallic camp, which had about 50,000 men. But they had only fortified the front of the camp. Crassus simply went around and attacked the rear. Caught by surprise, the Gauls tried to flee. However, Crassus's cavalry chased them. According to Crassus, only 12,000 survived the Roman victory. The tribes surrendered, and Rome now controlled most of southwest Gaul.

Caesar finished the campaign season by trying to defeat the coastal tribes. These tribes had allied with the Veneti. However, they outmaneuvered the Romans. They knew the local terrain, which was heavily forested and marshy. They used a strategy of retreating into these areas. They avoided battle with the Romans. Bad weather made the situation worse. Caesar could only raid the countryside. Realizing he would not meet the Gauls in battle, he withdrew for the winter. This was a setback for Caesar. Not defeating these tribes would slow his campaigns next year.

The legions spent the winter between the Saône and Loire rivers. This was on lands they had conquered that year. This was Caesar's punishment to the tribes for fighting Rome. Caesar also attended the important Luca Conference in April. This meeting gave him another five years as governor. This allowed him time to finish conquering Gaul. In return, Pompey and Crassus shared the consulship for 55 BC. This strengthened their political alliance.

Crossing the Rhine and English Channel (55 BC)

Caesar's campaigns in 55 BC were likely driven by a need for prestige. His political allies, Pompey and Crassus, were consuls. They were also his rivals and very famous. Caesar needed to stay in the public eye. His solution was to cross two bodies of water no Roman army had crossed before: the Rhine river and the English Channel.

Crossing the Rhine was due to Germanic and Celtic unrest. The Suebi had forced the Celtic Usipetes and Tencteri from their lands. These tribes crossed the Rhine looking for a new home. Caesar had denied their earlier request to settle in Gaul. The issue turned into war. The Celtic tribes sent 800 cavalry against 5,000 Roman auxiliaries (Gauls). They won a surprising victory. Caesar responded by attacking the defenseless Celtic camp. He killed the men, women, and children. Caesar claimed he killed 430,000 people. Modern historians find this number too high. But it is clear Caesar killed many Celts. His actions were so cruel that his enemies in the Senate wanted to prosecute him for war crimes. After the massacre, Caesar led the first Roman army across the Rhine. This quick campaign lasted only 18 days.

Historians believe Caesar's actions in 55 BC were a "publicity stunt." This explains the short campaign. Caesar wanted to impress Romans and scare Germanic tribes. He did this by crossing the Rhine in style. Instead of boats, he built a timber bridge in just ten days. He walked across, raided the Suebic countryside, and retreated. He burned the bridge before the Suebic army could gather.

He then turned to another feat no Roman army had done: landing in Britain. The stated reason to attack Britain was that Britonic tribes had helped the Gauls. But like most of Caesar's reasons for war, it was an excuse to gain fame in Rome.

Caesar's first trip to Britain was more an expedition than an invasion. He took only two legions. His cavalry could not make the crossing. Caesar crossed late in the season, in a hurry, on August 23. He planned to land in Kent, but Britons were waiting. He moved up the coast and landed, possibly at Pegwell Bay. But the Britons kept pace. They had a strong force, including cavalry and chariots.

The legions hesitated to land. Finally, the X legion's standard bearer jumped into the sea. He waded to shore. Losing the legion's standard in battle was the worst humiliation. The men landed to protect the standard bearer. After some delay, a battle line formed, and the Britons withdrew. Since Roman cavalry had not crossed, Caesar could not chase them.

Roman luck did not improve. A Roman foraging party was ambushed. Britons saw this as a sign of Roman weakness. They gathered a large force to attack. A short battle followed. Caesar gave few details, but Romans won. Again, the lack of cavalry prevented a decisive victory. The campaigning season was almost over. The legions were not ready to winter in Kent. Caesar withdrew back across the Channel.

Historians note Caesar narrowly escaped disaster again. Taking a small army with few supplies to a distant land was a poor choice. It could have led to Caesar's defeat, but he survived. He gained little in Britain, but just landing there was a huge achievement. It was a great propaganda victory. Caesar wrote about his exploits in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico. These writings kept Rome updated on Caesar's adventures. Caesar's goal of fame and publicity succeeded greatly. When he returned to Rome, he was hailed as a hero. He was given an unprecedented 20-day thanksgiving. He then began planning a proper invasion of Britain.

Invading Britain and Unrest in Gaul (54 BC)

Caesar's approach to Britain in 54 BC was much more thorough. New ships were built over the winter. Caesar now took five legions and 2,000 cavalry. He left the rest of his army in Gaul to keep order. Historians note Caesar took many Gallic chiefs he did not trust with him. This was so he could watch them. This shows Gaul was not fully conquered. Several revolts later in the year proved Gaul was still unstable.

Caesar landed without resistance. He immediately went to find the Britonic army. The Britons used guerrilla tactics to avoid direct fighting. This allowed them to gather a strong army under Cassivellaunus, king of the Catuvellauni. The Britonic army had better mobility with its cavalry and chariots. They easily avoided and harassed the Romans.

The Britons attacked a foraging party. They hoped to pick off the isolated group. But the party fought back fiercely and defeated the Britons. Most tribes then gave up resistance. Many surrendered and offered tribute. The Romans attacked Cassivellaunus's stronghold (likely modern Wheathampstead). He surrendered. Caesar demanded grain, slaves, and yearly tribute to Rome.

However, Britain was not very rich then. The Roman writer Cicero said there was no silver on the island. He said there was no hope for loot except slaves. Still, this second trip to Britain was a true invasion. Caesar achieved his goals. He had defeated the Britons and extracted tribute. They were now effectively Roman subjects. Caesar was lenient with the tribes. He needed to leave before stormy weather made crossing the channel impossible.

Revolts in Gaul

Things did not go smoothly back on the continent in 54 BC. Harvests had failed in Gaul that year. But Caesar still wintered his legions there. He expected the Gauls to feed his troops. He did realize harvests had failed. So he spread his troops out to not burden one tribe too much. But this isolated his legions, making them easier to attack. Gallic anger boiled over after the legions made camp for the winter. Tribes rebelled.

The Eburones, led by Ambiorix, had to host a legion and five cohorts. These were under Quintus Titurius Sabinus and Lucius Aurunculeius Cotta. Ambiorix attacked the Roman camp. He falsely told Sabinus that all Gaul was revolting. He also said Germanic tribes were invading. He offered Romans safe passage if they left their camp and returned to Rome. Sabinus believed Ambiorix, which historians call a very foolish move.

As soon as Sabinus left the camp, his forces were ambushed in a steep valley. Sabinus had not chosen the right formation for the terrain. The new troops panicked. The Gauls won decisively. Both Sabinus and Cotta were killed. Only a few Romans survived.

The total defeat of Sabinus spread the idea of revolt. The Atuatuci, Nervii, and their allies also rebelled. They attacked the camp of Quintus Cicero, brother of the famous orator Marcus Cicero. They told Cicero the same story Ambiorix told Sabinus. But Cicero was not as easily fooled. He strengthened the camp's defenses. He tried to send a messenger to Caesar. The Gauls began a fierce siege. They had captured Roman soldiers before. They used their knowledge of Roman tactics to build siege towers and earthworks. They then attacked the Romans almost continuously for over two weeks.

Cicero's message finally reached Caesar. He immediately took two legions and cavalry to relieve the siege. They marched quickly through Nervii lands, covering about 20 miles (32 km) a day. Caesar defeated the 60,000-strong Gallic army. He finally rescued Cicero's legion. The siege had killed 90 percent of Cicero's men. Caesar praised Quintus Cicero's toughness greatly.

Suppressing Unrest (53 BC)

The winter uprising of 54 BC was a disaster for the Romans. One legion was completely lost, and another almost destroyed. The revolts showed that Romans were not truly in control of Gaul. Caesar began a campaign to fully conquer the Gauls and prevent future resistance. He was down to seven legions. He needed more men. Two more legions were recruited, and one was borrowed from Pompey. The Romans now had 40,000–50,000 men.

Caesar began the brutal campaign early, before the weather warmed. He focused on a new strategy: demoralizing people and attacking civilians. He assaulted the Nervii. He focused on raiding, burning villages, stealing livestock, and taking prisoners. This strategy worked. The Nervii quickly surrendered. The legions returned to their winter camps until the campaign season fully started.

Once the weather warmed, Caesar launched a surprise attack on the Senones. They had no time to prepare for a siege or retreat to their oppidum. The Senones also surrendered. Attention turned to the Menapii. Caesar used the same raiding strategy he used on the Nervii. It worked just as well on the Menapii, who surrendered quickly.

Caesar's legions were split up to defeat more tribes. His commander Titus Labienus had 25 cohorts (about 12,000 men) and cavalry. They were in the lands of the Treveri (led by Indutiomarus). The Germanic tribes had promised to help the Treveri. Labienus knew his small force would be at a disadvantage. So, he tried to trick the Treveri into attacking on his terms.

He pretended to retreat. The Treveri fell for the trick. However, Labienus had made sure to pretend to retreat up a hill. This made the Treveri run uphill. By the time they reached the top, they were tired. Labienus stopped pretending to retreat and fought them. He defeated the Treveri in minutes. The tribe surrendered shortly after. In the rest of Belgium, three legions raided the remaining tribes. They forced widespread surrender, including the Eburones under Ambiorix.

Caesar now wanted to punish the Germanic tribes for helping the Gauls. He took his legions over the Rhine again by building a bridge. But again, Caesar's supplies failed him. This forced him to withdraw. He wanted to avoid fighting the still powerful Suebi while short on supplies. Still, Caesar had forced widespread surrender. He did this through a harsh campaign focused on destruction rather than battle. Northern Gaul was largely devastated. At the end of the year, six legions wintered. Two were in the lands of the Senones, two in the Treveri, and two in the Lingones. Caesar aimed to prevent a repeat of the previous disastrous winter. But given the brutality of Caesar's actions that year, an uprising could not be stopped by garrisons alone.

Vercingetorix's Revolt (52 BC)

Gallic fears about their future came to a head in 52 BC. This caused the widespread revolt Romans had long feared. The campaigns of 53 BC had been very harsh. The Gauls worried about their future. Before, they had not been united, which made them easy to conquer. But this changed in 53 BC. Caesar announced that Gaul was now a Roman province. This meant it was subject to Roman laws and religion.

This worried the Gauls greatly. They feared Romans would destroy their holy land, watched over by the Carnutes. Each year, druids met there to settle disputes between tribes. A threat to their sacred lands finally united the Gauls. Over the winter, the charismatic king of the Arverni tribe, Vercingetorix, formed a huge alliance of Gauls.

Caesar was still in Rome when he heard about the revolt. He rushed to Gaul to stop it from spreading. He went first to Provence to secure its defense. Then he went to Agedincum to counter the Gallic forces. Caesar took a winding route to the Gallic army. He wanted to capture several oppida for food. Vercingetorix had to stop his siege of the Boii capital of Gorgobina. The Boii had been allied to Rome since their defeat in 58 BC.

It was still winter, and Vercingetorix realized Caesar's detour was due to low Roman supplies. So, Vercingetorix planned to starve the Romans. He avoided direct attacks. Instead, he raided foraging parties and supply trains. Vercingetorix abandoned many oppida. He only defended the strongest ones. He made sure others and their supplies could not fall to Romans. Again, a lack of supplies forced Caesar's hand. He besieged the oppidum of Avaricum, where Vercingetorix had sought refuge.

Vercingetorix had originally opposed defending Avaricum. But the Bituriges Cubi persuaded him. The Gallic army camped outside the settlement. Even while defending, Vercingetorix wanted to abandon the siege and outrun the Romans. But the warriors of Avaricum did not want to leave.

Upon his arrival, Caesar quickly began building defenses. The Gauls constantly attacked the Romans and their foraging parties. They also tried to burn down the Roman camp. But even the harsh winter weather could not stop the Romans. They built a very strong camp in just 25 days. The Romans built siege engines. Caesar waited for a chance to attack the heavily fortified oppidum. He chose to attack during a rainstorm when guards were distracted.

Siege towers were used to assault the fort. Ballista artillery battered the walls. Eventually, the artillery broke a hole in a wall. The Gauls could not stop the Romans from taking the settlement. The Romans then looted Avaricum. Caesar took no prisoners and claimed Romans killed 40,000. The Gallic alliance did not fall apart after this defeat. This shows Vercingetorix's strong leadership. Even after losing Avaricum, the Aedui joined the alliance. This was another setback for Caesar's supply lines. He could no longer get supplies through the Aedui.

Vercingetorix then withdrew to Gergovia, his tribe's capital. He was eager to defend it. Caesar arrived as the weather warmed. Food for animals finally became available, which eased supply issues. As usual, Caesar quickly began building fortifications for the Romans. He captured territory closer to the oppidum.

What happened in the Battle of Gergovia is somewhat unclear. Caesar claimed he ordered his men to take a hill near the oppidum. Then he sounded a retreat. But no such retreat happened, and the Romans attacked the settlement directly. Historians think Caesar likely did not sound a retreat. They believe it was his plan all along to take the settlement. Caesar's doubtful claim was probably to distance himself from the Roman failure. Greatly outnumbered, the Roman attack ended in a clear defeat. Caesar claimed 700 of his men died, including 46 centurions. The actual numbers were likely much higher. Caesar withdrew from the siege. Vercingetorix's victory attracted many more Gallic tribes to his cause. Despite their loss, the Romans still convinced numerous Germanic tribes to join them after the battle.

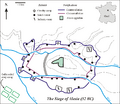

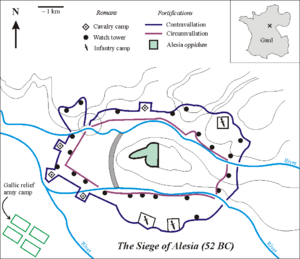

Siege of Alesia: End of the Revolt

Vercingetorix chose to defend the Mandubii oppidum of Alesia next. This would become the siege of Alesia. He gathered about 70,000–100,000 warriors. After the poor performance at Gergovia, Caesar felt a direct attack on the Gauls was not a good idea. So he decided to besiege the settlement and starve the defenders. Vercingetorix was fine with this. He planned to use Alesia as a trap. He wanted to launch a pincer attack on the Romans. He immediately called for a relief army.

Vercingetorix likely did not expect the intensity of Roman siege preparations. Modern archaeology suggests Caesar's preparations were not as complete as he described. But it is clear he built incredible siege works. Over a month, the Romans built about 25 miles (40 km) of fortifications. These included a trench for soldiers, an anti-cavalry moat, towers, and booby traps. The fortifications were dug in two lines. One protected from the defenders, and one from the relief army. Archaeological evidence suggests the lines were not continuous as Caesar claimed. They made good use of the local terrain. But they clearly worked.

Vercingetorix's relief army arrived quickly. But coordinated attacks by both defenders and the relief army failed to dislodge the Romans. After many attacks, the Gauls realized they could not overcome the impressive Roman siege works. At this point, it became clear that the Romans would outlast the defenders. The revolt was doomed. The relief army melted away.

Vercingetorix surrendered. He was held prisoner for six years. He was paraded through Rome and ceremonially executed in 46 BC.

After crushing the revolt, Caesar stationed his legions for winter across the defeated tribes' lands. This was to prevent further rebellion. He sent troops to protect the Remi, who had been loyal Roman allies. But resistance was not entirely over. Caesar had not yet fully subdued southwest Gaul.

Pacification of the Last Gauls (51 and 50 BC)

In the spring of 51 BC, the legions campaigned among the Belgic tribes. They aimed to stop any thoughts of an uprising. The Romans achieved peace. But two chiefs in southwest Gaul, Drappes and Lucterius, remained openly hostile. They had fortified the strong Cadurci oppidum of Uxellodunum.

Gaius Caninius Rebilus surrounded the oppidum. He began the siege of Uxellodunum. He focused on building camps, a circumvallation (a wall around the city), and cutting off Gallic access to water. Tunnels were dug to the spring that fed the city. Archaeological evidence of these tunnels has been found. The Gauls tried to burn down the Roman siege works, but failed. Eventually, the Roman tunnels reached the spring and diverted the water supply.

Not realizing the Roman action, the Gauls believed the spring drying up was a sign from the Gods. They surrendered. Caesar chose not to kill the defenders. Instead, he cut off their hands as an example.

The legions again wintered in Gaul. Little unrest occurred. All tribes had surrendered to the Romans. Little campaigning took place in 50 BC.

Caesar's Victory

In eight years, Caesar had conquered all of Gaul and part of Britain. He became very wealthy and gained a legendary reputation. The Gallic Wars gave Caesar enough power. He was able to wage a civil war and declare himself dictator. These events eventually led to the end of the Roman Republic. They also led to the establishment of the Roman Empire.

The Gallic Wars do not have a clear end date. Legions remained active in Gaul through 50 BC. Aulus Hirtius took over writing Caesar's reports on the war. The campaigns might have continued into Germanic lands. But the Roman civil war was coming. Caesar needed his legions to defeat his enemies in Rome. So, the legions in Gaul were pulled out in 50 BC.

The Gauls were not entirely subdued. They were not yet a formal part of the empire. But that task was left to Caesar's successors. Gaul would not be formally made into Roman provinces until the reign of Augustus in 27 BC. Several rebellions happened later. Roman troops remained stationed throughout Gaul. Historians think there could have been unrest in the region as late as 70 AD. But it was not as large as Vercingetorix's revolt.

The conquest of Gaul marked the beginning of almost five centuries of Roman rule. This had huge cultural and historical impacts. Roman rule brought Latin, the language of the Romans. This language later evolved into Old French, giving modern French its Latin roots. Conquering Gaul allowed the Empire to expand further into Northwestern Europe. Augustus would push into Germania. He reached the Elbe river. But he settled on the Rhine as the imperial border after the disastrous Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. The Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD, led by Claudius, also built on Caesar's invasions. Roman control would last, with only one interruption, until 406 AD.

Sources and History

Very few sources about the Gallic Wars survive. The Gauls did not record their history. So, their perspective has been lost. Julius Caesar's writings are the main source of information. This makes it hard for historians, as his account is biased in his favor. Only a few other works from that time mention the conflict. None are as detailed as Caesar's, and most rely on his story. The fact that he conquered Gaul is certain. The details, however, are less clear.

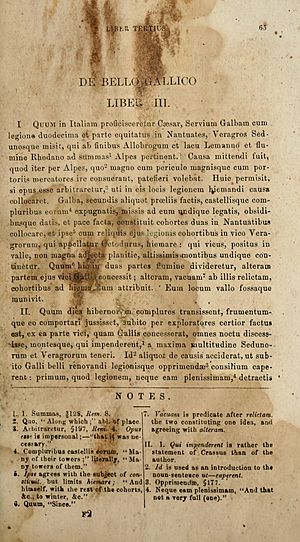

Caesar's Book: Commentarii de Bello Gallico

The main source from that time is Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico. This book was largely believed to be completely true until the 20th century. However, after World War II, historians began to question Caesar's claims.

For example, Caesar claimed he could estimate the Helvetii population. He said a census written in Greek was found in their camp. It supposedly showed 263,000 Helvetii and 105,000 allies. Of these, exactly one quarter (92,000) were fighters. But historians point out that such a census would have been hard for Gauls to do. It also makes no sense for non-Greek tribes to write it in Greek. Carrying so many stone or wood tablets during their migration would have been a huge task. Historians find it too convenient that exactly one quarter were fighters. This suggests Caesar likely exaggerated the numbers. Other writers from that time also estimated lower populations for the Helvetii. Some historians believe there were at most 20,000 migrating Helvetii, with 12,000 warriors. Others think there were no more than 50,000 Helvetii and allies.

Caesar claimed to have killed 430,000 people in a Celtic camp. Historians find this number impossibly high for the time. However, it is clear that Caesar killed a great many Celts. His actions to destroy a non-combatant camp were very brutal, even by Roman standards.

Ultimately, modern scholars see the Commentarii as a very clever piece of propaganda by Caesar. It was written to make Caesar seem much greater than he was. Caesar's straightforward writing style made it easy to accept his unbelievable claims. He wanted to show his fight as a justified defense against "barbarian" Gauls. This was important because Caesar was the aggressor, despite his claims. By making it seem like he won against huge odds and suffered very few losses, he reinforced the idea that he and the Romans were protected by the gods. He wanted to show they were destined to win against the "heathen barbarians" of Gaul.

Some historians argue that Caesar's campaign was not unusually brutal for its time. They note that Caesar generally tried to avoid unnecessary battles. He also tried to be more lenient than most generals of his era. Whether true or not, Caesar seems to try hard to appear morally superior. This allowed Caesar to compare himself favorably to the "barbarian" Gauls. He presented himself as the "perfect Roman citizen." While Caesar's work is full of propaganda, some historians believe it contains more truth than others think. Above all, it shows how Caesar saw himself and how he believed a leader should rule. Caesar's conquest of the Gauls would have been well-received in Rome. It would have been seen as a just peace.

In Literature

Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico, written in Latin, is a great example of clear Latin prose. It is studied intensely by Latin scholars. It is a classic text used to teach Latin today. It begins with the famous phrase "Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres", meaning "Gaul is a whole divided into three parts." The introduction is famous for its overview of Gaul.

The Gallic Wars have become a popular setting in modern historical fiction, especially in France and Italy. Also, the comic Astérix is set shortly after the Gallic Wars. In the comic, the main character's village is the last holdout in Gaul against Caesar's legions.

Images for kids

-

Caesar's Rhine Bridge, by John Soane (1814)

-

Denarius coin from 48 BC. It shows the head of a captive Gaul and a Britonic chariot.

-

The fortifications built by Caesar in Alesia. Inset: cross shows location of Alesia in Gaul (modern France). The circle shows the weakness in the north-western section of the fortifications.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de las Galias para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de las Galias para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |