Gaius Marius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

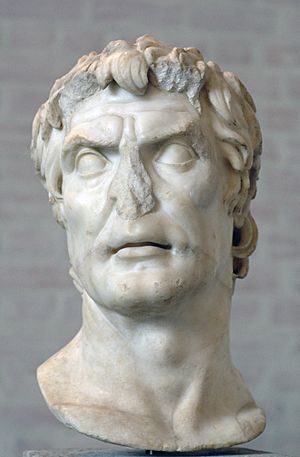

Gaius Marius

|

|

|---|---|

Reverse of a denarius of 101 BC, depicting Marius as triumphator in a chariot

|

|

| Born | c. 157 BC Cereatae, Italy

|

| Died | 13 January 86 BC (aged 70–71) |

| Office | Tribune of the plebs (119 BC) Governor of Hispania Ulterior (114 BC) Consul (107, 104–100, 86 BC) |

| Spouse(s) | Julia (aunt of Julius Caesar) |

| Children | Gaius Marius the Younger |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Numantine War Jugurthine War Cimbrian War Social War Bellum Octavianum |

| Awards | 2 Roman triumphs |

Gaius Marius (born around 157 BC – died 13 January 86 BC) was a famous Roman general and leader. He won important wars, like the Cimbric and Jugurthine wars. He was elected consul seven times, which was more than anyone before him. Marius also made big changes to the Roman army. He helped turn the army from part-time soldiers into a professional fighting force. He also improved the pilum, which was a type of javelin, and made the army's supplies better.

Marius came from a wealthy family in the Italian countryside. He started his military career serving with Scipio Aemilianus in 134 BC. This was during the Siege of Numantia. Later, he became a tribune of the plebs in 119 BC. He passed a law that made it harder for rich people to interfere in elections. He was barely elected praetor in 115 BC. After that, he became the governor of Further Spain, where he fought against bandits. When he came back from Spain, he married Julia, who was the aunt of Julius Caesar.

Marius became consul for the first time in 107 BC. He took command of the Roman forces in Numidia and ended the Jugurthine War. By 105 BC, Rome faced a new threat from the Cimbri and Teutones tribes. The Roman people elected Marius consul for a second time to fight them. Marius was consul every year from 104 to 100 BC. He defeated the Teutones at Aqua Sextiae and the Cimbri at Vercellae. Because of his victories, people called him "the third founder of Rome." The first two were Romulus and Camillus. However, Marius faced political problems during his sixth consulship in 100 BC. After this, he mostly stayed out of public life for a while.

Rome faced another big problem when the Social War started in 91 BC. Marius fought in this war, but he had limited success. He then got into a conflict with another Roman general, Sulla. This led to Marius being sent away to Africa in 88 BC. Marius came back to Italy during the War of Octavius. He took control of Rome and began a period of harsh rule in the city. He was then elected consul for a seventh time. He died shortly after, in 86 BC. Marius's life and career changed Roman politics. He showed that soldiers could be loyal to their commanders, not just to the Republic. This helped Rome change from a republic to an empire.

Life Story

Early Years

Marius was born in a small village called Cereatae in 157 BC. This village was near the town of Arpinum in Italy. His town had become part of Rome in the late 4th century BC. It only gained full Roman citizenship 30 years before Marius was born. Some ancient writers said Marius's father was a worker. But this is likely not true. Marius had connections with important families in Rome. He also ran for local office in Arpinum. This shows he came from a wealthy and important local family.

Many people in Rome looked down on Marius because he was a "new man." This meant he was the first in his family to reach high political office. But Marius was not poor. He was born into a family with a lot of inherited wealth, probably from large land holdings. His family was rich enough to support two sons in Roman politics. Marius's younger brother, Marcus Marius, also became involved in public life.

In 134 BC, Marius joined the army of Scipio Aemilianus as an officer. This was for a military trip to Numantia. It was clear that Marius was a very skilled soldier. Scipio Aemilianus noticed his talent. According to one story, Scipio once tapped Marius on the shoulder. He said, "Perhaps this is the man" when asked who would be his successor.

Even early in his career, Marius wanted to be a politician in Rome. He ran for election as a military tribune. This was an important military position. He was elected by all the voting groups because of his achievements. After this, he probably served with Quintus Caecilius Metellus Balearicus. He helped Metellus win a triumph (a victory parade).

Marius then became a plebeian tribune in 120 BC. He won with the help of the Metelli family. This was one of the most powerful families in Rome. Plutarch says that Marius went against his powerful supporters. He passed a law that limited how much rich people could interfere in elections. This law made voting more private. It stopped outsiders from bothering voters or seeing who they voted for. However, Marius soon upset the common people. He stopped a bill that would have given out more cheap grain. He said it would cost too much money.

In 117 BC, Marius tried to become an aedile but lost. This job required a lot of personal money. This shows Marius had a lot of wealth by this time. In 116 BC, he barely won election as praetor. He was accused of ambitus (election cheating). But Marius was found innocent. He spent a quiet year as praetor in Rome. In 114 BC, Marius was sent to govern Further Spain. He was there for two years. He cleared out bandits from mining areas. He came back to Rome in 113 BC with much more wealth.

He did not get a triumph when he returned. But he did marry Julia. She was the aunt of Julius Caesar. The Julii Caesares were a noble family. But they had not had much success in reaching the consulship. This marriage helped both families. Marius gained respect by marrying into a noble family. The Julii family gained energy and money.

Fighting in Numidia

The Jugurthine War started in 112 BC. It was because of a Numidian king named Jugurtha. He had killed his half-brothers and many Italians. He also bribed many Roman leaders. The first Roman army sent to Numidia was bribed to leave. The second army was defeated and shamed. These failures made Romans lose trust in their leaders.

Marius had disagreed with the Metelli family before. But they still chose him as a legate (a high-ranking officer). In 109 BC, Marius joined Consul Quintus Caecilius Metellus in his fight against Jugurtha. Marius was Metellus's main assistant. Metellus used Marius's strong military skills. Marius used this time to improve his chances for consul.

During the Battle of the Muthul, Marius probably saved Metellus's army. Jugurtha had cut off the Romans from water. The Romans had to fight in the desert. The Numidian cavalry spread out the Romans. Each Roman group fought alone. Marius quickly reorganized some groups. He led 2,000 men to join Metellus. Together, they attacked the Numidian foot soldiers. They then attacked the Numidian cavalry from behind. The Romans took control, and the Numidians had to leave.

By 108 BC, Marius wanted to run for consul. Metellus did not want Marius to go back to Rome. He told Marius to wait and run with Metellus's young son. But Marius did not listen. He started campaigning for consul. A fortune-teller in Utica told him he would have a great career. This made Marius even more determined.

Marius earned the respect of the soldiers. He ate with them and shared their hard work. He also won over Italian traders. He told them he could capture Jugurtha quickly with half of Metellus's troops. Both groups wrote home praising Marius. They said he could end the war fast, unlike Metellus.

During the winter of 109–108 BC, a Roman garrison was attacked. The commander, Titus Turpilius Silanus, escaped unharmed. Marius urged Metellus to sentence Silanus to death for cowardice. But then Marius turned on Metellus. He said the sentence was too harsh. Marius also sent letters to Rome. He claimed Metellus loved his power too much. Metellus, worried about Marius, let him return to Rome. Marius had just enough time to campaign for the consular elections.

There was growing pressure in Rome for a quick victory. Marius was elected consul for 107 BC. He campaigned by saying Metellus was too slow. The Senate tried to stop Marius from taking command in Numidia. But Marius had an ally, Tribune Titus Manlius Mancinus. Mancinus convinced the people's assembly to give Marius command. Metellus refused to hand over command to Marius. He returned to Rome. The Senate gave Metellus a triumph and the special name Numidicus.

Marius needed more soldiers in Numidia. Normally, only citizens who owned property could join the army. But Marius found it hard to recruit enough men this way. He decided to ask for volunteers instead. He especially wanted veterans and men without property. These men were called capite censi. Marius promised them victory and riches. With his new army, Marius sailed to Africa. He left his cavalry with his new assistant, Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

Ending the war was harder than Marius had boasted. Jugurtha fought a guerrilla war. Marius arrived late in 107 BC. But he still won a battle near Cirta. At the end of 107, he surprised Jugurtha. He marched his army through the desert to Capsa. After the town surrendered, he killed all the adult men. He enslaved the rest and destroyed the town. He gave the loot to his soldiers. He kept pushing Jugurtha's forces south and west into Mauretania. Marius was supposedly unhappy with Sulla as his assistant. But Sulla proved to be a very good officer.

Jugurtha tried to get his father-in-law, King Bocchus of Mauretania, to join him. In 106, Marius marched his army far west. He captured a fortress near the Molochath River. This move brought him close to Bocchus's land. This finally made Bocchus act. In the desert, Marius was surprised by a combined army. It was made of Numidians and Mauretanians. Marius was not ready. His men had to form defensive circles. The enemy attacked with horsemen. Marius and his main force were trapped on a hill. Sulla and his men were on another hill nearby. The Romans held them off until evening. The Africans then left. The next morning, the Romans surprised the enemy camp. They completely defeated the Numidian-Mauretanian army. Marius then marched east to winter in Cirta. The African kings bothered the Roman retreat. But Sulla, leading the cavalry, pushed them back. It was clear that Rome could not defeat Jugurtha's tactics by just fighting. So, Marius started talking with Bocchus again.

Finally, Marius made a deal with Bocchus. Sulla, who was friends with Bocchus's court, would go into Bocchus's camp. He would receive Jugurtha as a hostage. Sulla agreed, even though it was risky. Jugurtha's remaining followers were killed. Bocchus handed Jugurtha over to Sulla in chains. Bocchus took over the western part of Jugurtha's kingdom. He was recognized as a friend of Rome. Jugurtha was put in a Roman prison. He died after being paraded in Marius's triumph in 104 BC.

After the triumph, Sulla and Marius argued over who deserved credit for capturing Jugurtha. Sulla was Marius's assistant. So, by Roman custom, Marius should get the credit. But Sulla and his noble friends said Sulla was directly responsible. This was to make Marius's victory seem less important. This argument was the start of their "unending hatred."

Fighting the Germanic Tribes

In 109 BC, a Germanic tribe called the Cimbri defeated a Roman army in Gaul. This defeat hurt Rome's reputation. It also caused problems with Celtic tribes in southern Gaul. In 107, another Roman consul was completely defeated. His army was shamed. The next year, 106 BC, Consul Quintus Servilius Caepio went to Gaul with a new army. Caepio stayed in command the next year. The new consul for 105 BC, Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, also went to Gaul with another army. Caepio did not like Mallius. He refused to work with him.

The Cimbri and another tribe, the Teutones, appeared near the Rhône River. Caepio was on one side of the river. He refused to help Mallius on the other side. The Senate could not make them work together. This led to disaster for both generals. At the Battle of Arausio, the Cimbri easily defeated Caepio's legions. Caepio's fleeing men crashed into Mallius's troops. Both Roman armies were trapped against the river. The Cimbri, who had many more warriors, destroyed them.

Rome needed successful generals. So, the Roman people did something against the law. They elected Marius consul for a second time, even though he was not in Rome. This was unusual, but the people set aside the rules. They made Marius consul.

As Consul

Marius was still in Africa when he was elected consul for 104 BC. At the start of his consulship, Marius returned from Africa. He had a spectacular triumph (victory parade). He brought Jugurtha and riches from North Africa to show the Roman people. Jugurtha, who had once said he would destroy Rome, died in a Roman prison. Marius was sent to Gaul to deal with the Cimbri.

The Cimbri, after their big victory, marched west into Spain. Marius had to rebuild the Roman legions in Gaul from scratch. He used experienced soldiers as a core. He again got permission to ignore property rules for recruiting. With his new fame, he raised an army of about 30,000 Romans and 40,000 Italian allies. He set up a base near Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence). There, he trained his men.

His old assistant, Sulla, was one of his officers. This shows they were still on good terms then. In 104 BC, Marius was elected consul again for 103 BC. The people probably re-elected him to avoid another problem like Caepio and Mallius. In 103 BC, the Germans still did not come out of Spain. Marius's fellow consul died. So Marius had to return to Rome to hold new elections. He had not ended the Cimbrian conflict yet. So, it was not certain he would win re-election. But a young tribune, Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, helped him. Marius was elected consul again for 102 BC. His fellow consul was Quintus Lutatius Catulus. During these years, Marius was very busy. He trained his troops, built a spy network, and talked with Gallic tribes. He also made big changes to the Roman army.

Changes to the Army

Rome had a problem finding enough soldiers in the 2nd century BC. The Cimbri returned, and more soldiers were needed. In 107 BC, Marius was allowed to ignore property rules for soldiers. This was for the war against Jugurtha. Recruiting volunteers without property was unusual. But no one was forced to join. So, it was not illegal. Historians think Marius did this to avoid making property owners angry. He might also have done it because poor people were eager to serve. With the Cimbri threat from 105 to 101, he got another special permission.

After the disasters of the Cimbrian War, the need for men became even greater. Marius and other leaders started recruiting openly. This was a big change from the old system. It meant armies were no longer just made of citizens who owned land. It might have taken some time for poor city people to join the army. This might have become common only during the Social War. But recruiting poor people did not completely change the army. Many poor farmers still had enough property to join. Roman armies were still mostly made of people from the countryside. But the need for men meant that soldiers became very loyal to their generals. Generals were seen as friends and helpers.

Marius also changed how his men were trained and supplied. Instead of large baggage trains, Marius made his soldiers carry all their gear. This included weapons, blankets, clothes, and food. Roman soldiers were called "Marius's mules" because of this. He also improved the pilum, a javelin. After his changes, the javelin would bend when it hit an enemy. This made it unusable for the enemy. Marius is known for many reforms. But there is no proof that he changed the army's fighting unit from the maniple to the cohort.

Battles with the Germanic Tribes

Marius was re-elected consul for 102 BC. This proved to be a good decision. The Cimbri returned from Spain. With other tribes, they moved towards Italy. The Teutones and their allies, the Ambrones, went south. They planned to attack Italy from the west. The Cimbri tried to cross the Alps from the north. The Tigurini, another allied Celtic tribe, tried to cross from the northeast. The two Roman consuls split their forces. Marius went west into Gaul. Catulus stayed to defend the Italian Alps.

In the west, Marius avoided fighting the Teutones and Ambrones directly. He stayed inside a strong camp. He fought off their attacks. When they failed to take his camp, the Teutones and their allies moved on. Marius followed them. He waited for the right moment to attack. Near Aquae Sextiae, a small fight broke out. Roman camp servants getting water fought some Ambrones. This turned into a big battle. The Romans defeated about 30,000 Ambrones. The next day, the Teutones and Ambrones attacked the Roman position. But a Roman officer, Marcus Claudius Marcellus, attacked their side with 3,000 men. This turned the battle into a huge defeat for the Germans. Estimates say 100,000 to 200,000 were killed or captured. Marius sent a report to Rome. It said 37,000 well-trained Romans had defeated over 100,000 Germans.

Marius's fellow consul in 102 BC, Quintus Lutatius Catulus, did not do as well. He lost some men in a small fight near Tridentum. Catulus then pulled back. The Cimbri entered northern Italy. The Cimbri stopped in northern Italy. They waited for more fighters from other mountain passes.

Soon after Marius won at Aquae Sextiae, he heard good news. He had been re-elected for his fourth consulship in a row. This was his fifth consulship overall. He would be consul for 101 BC. His fellow consul would be his friend Manius Aquillius. After being elected, Marius went back to Rome. He announced his victory at Aquae Sextiae. He then marched north with his army to join Catulus. Catulus's command was extended. This was because Marius's new fellow consul was sent to stop a slave revolt in Sicily.

In late July 101 BC, Marius met with the Cimbri. The Cimbri threatened the Romans. They said the Teutones and Ambrones were coming. Marius told the Cimbri that their allies had been destroyed. Both sides then got ready for battle. In the Battle of Vercellae, Rome completely defeated the Cimbri. Sulla's cavalry surprised them. Catulus's foot soldiers held them down. Marius attacked their sides. The Cimbri were slaughtered. The survivors were enslaved. Over 120,000 Cimbri died. The Tigurini gave up trying to enter Italy and went home.

After 15 days of celebration, Catulus and Marius had a joint triumph. But Marius was called "the third founder of Rome." People believed Marius deserved most of the credit for ending the war. At the same time, Marius's fellow consul, Manius Aquillius, defeated the slave revolt in Sicily. Marius had saved Rome. He was at the peak of his power. He wanted another consulship. He wanted to get land for his veteran soldiers. He also wanted to make sure he got credit for his military wins. Marius was elected consul for 100 BC. His fellow consul was Lucius Valerius Flaccus. Plutarch says Marius also helped his colleague win. This was to stop his rival, Metellus Numidicus, from getting a seat.

Sixth Consulship

During Marius's sixth consulship in 100 BC, Lucius Appuleius Saturninus was a tribune. He wanted reforms similar to those of the Gracchi brothers. Saturninus caused a political rival to be killed. He then pushed for laws that would send Marius's former commander, Metellus Numidicus, into exile. He also wanted to lower the price of grain given out by the state. And he wanted to give land to Marius's war veterans. Saturninus's bill gave land to all veterans, including Italian allies. Some Roman citizens did not like this. Marius, who was Italian, supported the rights of the allies. He even gave citizenship for brave actions.

Marius worked with Saturninus and his ally Glaucia. They passed the land bill and exiled Metellus Numidicus. But then Marius distanced himself from their more extreme ideas. Around election time, Marius tried to stop Glaucia from running for consul. Saturninus and Glaucia had an opponent, Gaius Memmius, killed. This was during the consular elections for 99 BC. The elections were then delayed. The Senate reacted strongly to Saturninus. They ordered Roman officials to take action to stop the unrest.

Marius gathered volunteers from the city and his veterans. He cut off the water supply to the Capitoline hill. He quickly besieged Saturninus's defenses. Saturninus and Glaucia surrendered. Marius tried to keep them safe. He locked them inside the senate house to await trial. But an angry crowd broke into the building. They threw roof tiles at the prisoners below. Many inside were killed. Glaucia was also dragged from his house and killed.

By following the Senate's orders, Marius tried to show them he was on their side. The Senate had always been suspicious of him. Marius wanted to be respected like other great "new men" of his time.

At the end of his consulship, Plutarch says Marius had upset both senators and common people. But it is unlikely Marius was completely abandoned. Historians say Marius entered a period of semi-retirement. He became an elder statesman. This meant he was less active in public life.

The 90s BC

After the events of 100 BC, Marius first tried to stop Metellus Numidicus from returning from exile. But he saw it was impossible. So, Marius decided to travel east to Galatia in 98 BC. He said he was fulfilling a promise to a goddess.

Plutarch says this was a big humiliation for Marius. He was seen as disliked by both nobles and common people. He even had to give up running for censor in 97 BC. Plutarch also says Marius tried to make Mithridates VI of Pontus declare war on Rome. He hoped Rome would need his military skills again. But historians say this story is probably just a rumor. Other scholars think Marius's trip was planned by the Senate. They wanted him to investigate Mithridates' actions in Cappadocia.

However, Marius's "humiliation" did not last long. Around 98–97 BC, he received a great honor. He was elected to the college of priestly augurs while he was away in Asia Minor. Also, Marius's presence at the trial of his friend Manius Aquillius in 98 BC was enough to get him found innocent. This happened even though Aquillius seemed guilty. Marius also successfully defended T. Matrinius in 95 BC. Matrinius was an Italian who Marius had given Roman citizenship. He was being tried under a new citizenship law.

The Social War

While Marius was away and after he returned, Rome had some years of peace. But in 95 BC, Rome passed a law. It expelled all residents from the city who were not Roman citizens. In 91 BC, Marcus Livius Drusus became tribune. He suggested a big reform plan. It included land reform and grain distribution for the poor. It also wanted to give citizenship to Italians. This was to make up for land reform affecting Italian property. And it wanted to add more equestrians to the Senate. Marius did not seem to have a strong opinion on the Italian citizenship question. But Drusus was killed. After this, many Italian states rebelled against Rome. This started the Social War of 91–87 BC. It was named after the Latin word for allies, socii.

Marius was called back to serve as a legate. He served with his nephew, Consul Publius Rutilius Lupus. Lupus died in an ambush by the Marsi tribe. Marius, leading another group of men, crossed the river at a different spot. He captured the Marsic camp. He then marched on the Marsi. With Marius controlling their camp and supplies, the Marsi had to retreat. Marius sent the bodies of Lupus and his officers back to Rome. Marius then took command of Lupus's army and reorganized it. The Senate decided to give joint command to Marius and Praetor Quintus Servilius Caepio the Younger. Marius had expected to be in sole command. He did not get along with Caepio. This led to bad results. Caepio left on his own and was attacked by the Marsi. Caepio's entire column of men was destroyed. It is said he was killed by Quintus Poppaedius Silo, a Marsi general.

Marius was now in sole command. He continued fighting the Marsi and their allies. After much maneuvering, the Marsi and Marruncini were defeated. This happened in a battle where Marius worked with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Sulla was his old assistant from the Jugurthine and Cimbrian wars. Together, they killed 6,000 rebels. They also captured 7,000. Marius did not follow up on this success. This was probably because he did not trust his men's morale. He refused to fight the enemy directly. Poppaedius Silo challenged him. He said, "If you are such a great general, Marius, why not come down and fight?" Marius replied, "Well, if you think you are any good a general, why don't you try to make me?"

By 89 BC, Marius had left the war. He might have left because of illness. Or he might have felt he was not getting enough credit. It is also possible his command was not renewed because he had not been very successful.

The Italian war for citizenship was difficult. In 90 BC, a law was passed. It granted citizenship to Italians who were not yet fighting. In early 89 BC, the war was slowing down. The Senate sent Lucius Porcius Cato to take over Marius's troops. Cato soon forced Marius to resign his position. He claimed Marius was in poor health.

Marius's efforts in this war brought him few honors. But he served at a high level and won some battles. This experience probably made him want more commands and glory. This led him to seek command in the east.

Sulla and the First Civil War

During the Social War, one of Marius's friends, Manius Aquillius, had encouraged kingdoms to invade Pontus. In response, King Mithridates of Pontus invaded those kingdoms. He also invaded Roman lands in Asia. Mithridates defeated Aquillius's small forces. He then marched across the Bosphorus. Aquillius retreated. The Social War was over. There was a chance for a glorious and rich conquest. So, there was a lot of competition in the consular elections for 88 BC. Finally, Lucius Cornelius Sulla was elected consul. He received command of the army going to Pontus.

After news of Mithridates' actions reached Rome, Marius thought about being consul for a seventh time. A tribune, Publius Sulpicius Rufus, was also working on proposals. He wanted to give the new Italian citizens voting rights. Marius likely pushed for this. He also wanted a seventh consulship. This would give him a strong political base. Sulpicius's proposals caused a big uproar in Rome. This led to a riot. Consul Sulla was forced to hide in Marius's house. They reached a compromise. The voting bill would pass. Sulla would prepare to go east.

After Sulla left Rome to prepare his army, Sulpicius passed his laws. He added a rule that gave Marius command in Pontus. This was very unusual. Marius was a private citizen and held no office. Marius then sent two of his officers to take command from Sulla. These actions were foolish. Sulla refused to give up his post. All but one of his own officers opposed Sulla's decision. But Sulla killed Marius's officers. He rallied his troops to his personal flag. He told them to defend him against Marius. Ancient sources say Sulla's soldiers were loyal. They worried they would stay in Italy. They thought Marius would raise his own veterans. These veterans would then get all the riches. Marius's group sent two tribunes to Sulla's legions. But Sulla's troops quickly killed the tribunes.

Sulla then ordered his troops to march slowly on Rome. This was a huge event. Marius had not expected it. No Roman army had ever marched on Rome before. It was against the law and old traditions. When it was clear Sulla would take Rome by force, Marius tried to defend the city. He used gladiators. But Marius's makeshift force was no match for Sulla's legions. Marius was defeated and fled the city. He barely escaped capture and death many times. He finally found safety with his veterans in Africa. Sulla and his supporters in the Senate declared 12 men outlaws. They sentenced Marius, his son, Sulpicius, and other allies to death. Sulpicius was executed. But many Romans did not approve of Sulla's actions.

Some who opposed Sulla were elected to office in 87 BC. Gnaeus Octavius, a supporter of Sulla, and Lucius Cornelius Cinna, a supporter of Marius, were elected consuls. Sulla wanted to show he believed in the Republic. Sulla was again confirmed as the commander for the campaign against Mithridates. So, he took his legions out of Rome and marched east to war.

Seventh Consulship and Death

While Sulla was fighting in Greece, a conflict broke out in Rome. It was between Sulla's conservative supporters and Cinna's popular supporters. The fight was over voting rights for Italians. Cinna was forced to flee Rome. But he gathered strong Italian support. He had about 10 legions, including the Samnites. Marius and his son then returned from exile in Africa. They had an army they raised there. They joined Cinna to remove Octavius. Marius demanded that his banishment be lifted by law. Cinna's much larger army forced the Senate to open the city gates.

They entered Rome. They began killing Sulla's main supporters. This included Octavius. Many important people were killed. Marius and Cinna also declared Sulla an enemy of the state. They took away his command in the east.

Marius and Cinna were both responsible for the deaths. But it is unlikely they killed everyone in their path. The killings probably aimed to scare their political opponents. With rivals scared, elections were held for 86 BC. Marius and Cinna were elected consuls in an unusual way. Within two weeks of becoming consul for the seventh time, Marius died.

Plutarch gives several ideas about Marius's death. One says Marius got sick with a lung disease. Another says Marius talked with friends about his achievements. He said a smart man should not leave things to chance. Plutarch also says Marius had a delusion. He thought he was in command of the Mithridatic War. He started acting like he was on a battlefield. Finally, Plutarch says Marius was always ambitious. On his deathbed, he regretted not achieving all he could. This was despite his great wealth and being consul more times than anyone before him.

After Marius died, Lucius Valerius Flaccus was elected to replace him as consul. Flaccus was immediately sent with two legions to fight Mithridates. He was to fight alongside Sulla, but not with him. Marius is sometimes blamed for the killings. But his sudden death likely helped shift blame. It also avoided a change in policy. Cinna and another consul, Carbo, continued the civil war. They were eventually defeated by Sulla's army. Sulla then made himself dictator.

Marius's Impact

Marius was a very successful Roman general and politician. Ancient writers often said he had endless ambition.

However, historians say this view is not entirely fair. Marius's efforts to become consul and gain power were normal for politicians then. Marius's example had a big impact. His five consulships in a row gave one man huge power for a long time. This was seen as necessary to save Rome.

But Marius died "hated by many." His unrealistic dreams of more victories might have caused the disastrous civil war of 87 BC. His ambition overcame his good judgment. This led to the start of the Roman revolution. The old Roman Republic was based on equal power among officials and short terms in office. The Republic could not survive Marius and his ambitions.

Changes to the Army

Ancient writers like Plutarch and Sallust criticized Marius's army reforms. They said these reforms made soldiers loyal only to their generals. They said soldiers depended on generals for pay and benefits. But historians say this loyalty did not start with Marius. His reforms were probably meant to be temporary. They were to deal with the big threats from Numidia and the Cimbrian tribes. Also, armies in the late Republic were similar to those in the middle Republic. By 107 BC, ignoring property rules for soldiers was common. Marius's reforms just made this official. It was needed to find enough men. It was also easier to recruit city volunteers than to force farmers to join.

Soldiers became more willing to fight other Romans after the Social War. If Sulla's army had not marched on Rome, things would have been very different. But it is unclear if this willingness came from the reforms themselves. It might have come from the environment during and after the Social War. This war weakened the Roman government's power.

However, promising land after service had political effects. The decision to recruit poor citizens was fully felt later. This was when soldiers needed to be settled. War spoils were not enough to support soldiers long-term. So, it became common to give land for veteran colonies. This usually happened in other countries. During Marius's lifetime, there were no big fights over veteran land grants. But later, passing laws for these colonies became very difficult.

Assemblies and Foreign Affairs

Marius often used the Assemblies to overturn Senate commands. This had bad effects on Rome's stability. The Senate usually chose generals for commands by drawing lots. This avoided conflicts of interest. Marius's use of the Assemblies to remove Metellus from command in Numidia ended this system. It ended shared rule in foreign affairs. Later, using the people's assemblies became the main way to give commands to generals. This led to more personal rivalries. It also made it harder to govern Rome. The rewards from controlling the Assemblies were too tempting for future politicians.

Marius's attempt to use the Assemblies to replace Sulla for the Mithridatic War was unheard of. Never before had laws been passed to give commands to someone who held no official title.

Timeline

Offices Held

Table of Offices

The following table shows the offices Marius held:

| Year (BC) | Office | Colleague | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 121? | Quaestor | ||

| 119 | Tribune of the plebs | ||

| 115 | Praetor | ||

| 114 | Promagistrate (pro praetore?) | Governor of Farther Spain | |

| 109–08 | Legate (lieutenant) | Under Metellus in Numidia | |

| 107 | Consul | Lucius Cassius Longinus | Commanded in Numidia |

| 106–05 | Proconsul | Commanded in Numidia | |

| 104–01 | Consul |

|

Fought the Cimbri and Teutones |

| 100 | Consul | Lucius Valerius Flaccus | Dealt with Saturninus and Glaucia |

| 97 | Legate (ambassador) | ||

| 90? | Legate (lieutenant) | Served in the Social War | |

| 88–87 | Proconsul | Served in the Social War | |

| 86 | Consul | Lucius Cornelius Cinna | Died shortly after taking office |

Consulships

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ser. Sulpicius Galba |

Roman consul 107 BC With: L. Cassius Longinus |

Succeeded by Q. Servilius Caepio |

| Preceded by P. Rutilius Rufus |

Roman consul 104–100 BC With: C. Flavius Fimbria L. Aurelius Orestes Q. Lutatius Catulus Manius Aquillius L. Valerius Flaccus |

Succeeded by M. Antonius |

| Preceded by Cn. Octavius |

Roman consul 86 BC With: L. Cornelius Cinna |

Succeeded by L. Valerius Flaccus as suffect |

|

See also

In Spanish: Cayo Mario para niños

In Spanish: Cayo Mario para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |