Urnfield culture facts for kids

|

|

| Geographical range | Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Late Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 1300–750 BC |

| Major sites | Burgstallkogel (Sulm valley), Ipf (mountain), Ehrenbürg |

| Preceded by | Tumulus culture, Vatya culture, Encrusted Pottery culture, Vatin culture, Terramare culture, Apennine culture, Noua culture, Ottomány culture |

| Followed by | Hallstatt culture, Lusatian culture, Proto-Villanovan culture, Villanovan culture, Canegrate culture, Golasecca culture, Este culture, Luco culture, Iron Age France, Iron Age Britain, Iron Age Iberia, Basarabi culture, Cimmerians, Thracians, Dacians, Iron Age Greece |

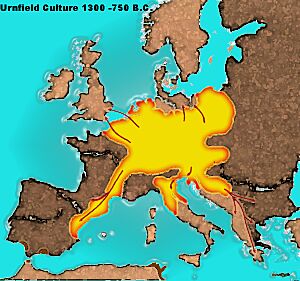

The Urnfield culture was a way of life for people in Central Europe during the Late Bronze Age. It lasted from about 1300 to 750 BC. The name "Urnfield" comes from how these people buried their dead. They would burn the bodies and then put the ashes into special pots called urns. These urns were then buried together in large areas, like fields.

This culture spread across much of Europe. It followed the Tumulus culture and was later replaced by the Hallstatt culture. Some experts think the Urnfield culture might be linked to the early forms of Celtic languages. Around 1000 BC, the Urnfield way of life reached Italy, northwestern Europe, and even the Pyrenees mountains. During this time, strong settlements on hilltops and new ways of working with bronze also became common.

Contents

- Understanding the Urnfield Timeline

- Where the Urnfield Culture Came From

- Where the Urnfield Culture Was Found

- Cultures Connected to Urnfield

- Movements and Changes

- Different Groups of People

- Urnfield Settlements

- Urnfield Tools and Art

- Early Use of Iron

- Urnfield Economy and Daily Life

- Numbers and Symbols

- Golden Hats

- Funerary Customs

- Religious Beliefs

- Genetics and Ancestry

Understanding the Urnfield Timeline

The Urnfield culture existed during the Late Bronze Age. It is divided into different time periods, which archaeologists call phases. These phases help us understand how the culture changed over time.

| Central European Bronze Age | |

| Late Bronze Age | |

| Ha B2/3 | 800–950 BC |

| Ha B1 | 950–1050 BC |

| Ha A2 | 1050–1100 BC |

| Ha A1 | 1100–1200 BC |

| Bz D | 1200–1300 BC |

| Middle Bronze Age | |

| Bz C2 | 1300–1400 BC |

| Bz C1 | 1400–1500 BC |

| Bz B | 1500–1600 BC |

| Early Bronze Age | |

| Bz A2 | 1600–2000 BC |

| Bz A1 | 2000–2300 BC |

The Urnfield culture includes phases called Hallstatt A and B (Ha A and B). These are part of a system created by Paul Reinecke. It's important not to confuse these with the later Hallstatt culture (Ha C and D), which came during the Iron Age.

Here are the main sub-phases of the Urnfield culture:

| Phase | Date (BC) |

|---|---|

| BzD | 1300–1200 |

| Ha A1 | 1200–1100 |

| Ha A2 | 1100–1000 |

| HaB1 | 1000–800 |

| HaB2 | 900–800 |

| Ha B3 | 800–750 |

Where the Urnfield Culture Came From

The Urnfield culture slowly developed from the earlier Tumulus culture. You can see this change in their pottery and in how they buried their dead. In some parts of Germany, people used both cremation and traditional burial at the same time.

The idea of burning bodies (cremation) is thought to have started in Hungary. It was common there since the first half of the second millennium BC. Even earlier, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture in modern-day Romania and Ukraine practiced cremation around 5500 BC.

Where the Urnfield Culture Was Found

The Urnfield culture covered a large area. It stretched from western Hungary to eastern France, and from the Alps mountains almost to the North Sea.

Archaeologists have found different local groups within the Urnfield culture. These groups are mostly known by the different styles of their pottery.

- South-German Urnfield culture: Found in areas like Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg.

- Lower-Rhine Urnfield culture: Found in places like Hesse and the Dutch Delta region.

- Middle-Danube Urnfield culture: Found in Moravia, Austria, Slovakia, and Hungary.

Sometimes, the items found from these groups show clear borders. This might mean that different tribes or political groups existed. However, metal objects were often found over much wider areas. This suggests that special workshops made metal goods for important people across large regions.

Cultures Connected to Urnfield

The Lusatian culture in central Europe was part of the Urnfield tradition. It continued into the Iron Age without much change.

In Italy, cultures like the Canegrate and Proto-Villanovan (Late Bronze Age) and the early Iron Age Villanovan culture were similar to the Urnfield culture. The Italic peoples, who later founded Ancient Rome, are thought to have come from the Urnfield and Tumulus culture people who lived in Italy.

The Golasecca culture in northern Italy also developed from the Canegrate culture. The language spoken by the Golasecca people was Celtic. This makes it likely that the language in western Urnfield areas was also Celtic or an early form of it.

The Urnfield culture's influence reached the northeastern Iberian coast. Here, the Celtiberians adopted some of its burial customs. The spread of Celtic languages in this area might be linked to skilled metalworkers from the early Urnfield culture.

Movements and Changes

Many hidden collections of objects (called hoards) and strong, fortified settlements were found in the Urnfield culture. Some experts think this shows a time of widespread fighting and big changes.

Around the time the Urnfield culture began, there were major problems in the Eastern Mediterranean. These included:

- The end of the Mycenean culture around 1200 BC.

- The destruction of Troy VI around 1200 BC.

- Battles of Ramses III against the Sea Peoples (1195–1190 BC).

- The end of the Hittite empire in 1180 BC.

Some scholars believe there was a large wave of migrations across Europe during this time.

Different Groups of People

Because there were many different regional groups in the Urnfield culture, it's unlikely that everyone belonged to the same ethnic group. Some researchers believe these groups were early forms of different peoples. These include the proto-Celts, proto-Italics, and others.

These groups might have moved to their historical locations later. This movement might have been caused by climate changes. These communities, led by warrior leaders, brought new burial customs, new pottery styles, and a lot of metal objects. They also brought new religions and Indo-European languages to parts of Western and Southern Europe.

Urnfield Settlements

The number of settlements grew a lot compared to the earlier Tumulus culture. Many of these settlements were fortified, meaning they had strong defenses. They were often built on hilltops or in river bends. They had strong walls made of stone or wood.

Open settlements (not fortified) were also common. Houses were often large, with three or four sections. They were built with wooden posts and walls made of wattle and daub (woven branches covered with mud). Some pit dwellings were also used, perhaps as cellars.

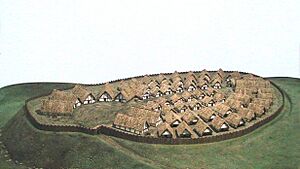

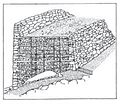

Fortified Hilltop Settlements

Fortified hilltop settlements became very common during the Urnfield period. Often, a steep hill was chosen, so only part of the area needed to be defended. Walls were built using local materials like dry stones or wood frames filled with stones or soil.

Metalworking was often done in these fortified settlements. For example, at Runder Berg in Germany, 25 stone molds for casting metal were found. These hillforts are seen as important central places. Some experts think the rise of hillforts shows that there was more warfare. Most of these hillforts were left empty at the end of the Bronze Age.

Examples of fortified settlements include Ipf in Germany, Burgstallkogel in Austria, and Biskupin in Poland.

The Bullenheimer Berg in Germany was a large, walled, city-like place in the later Urnfield period. It had many buildings, including courtyard-style homes. The fortified settlement on the Ehrenbürg was another important center. It was home to powerful leaders.

Corneşti-Iarcuri in Romania was the largest prehistoric settlement in Europe. It was almost 6 km wide, with four lines of defenses. It had an inner settlement about 2 km wide. Studies show it was a well-organized, city-like place during the Urnfield period. Building its walls alone required moving about 824,000 tons of earth.

These "mega forts" like Corneşti-Iarcuri were surrounded by many smaller settlements. They show a move towards large fortified sites across Europe in the Late Bronze Age. This might have been a response to new ways of fighting wars. The similar design and objects found suggest that these societies were organized under a common political system.

Open Settlements

Urnfield houses had one or two main sections. Some were small, about 4.5 m by 5 m. Others were much longer, up to 20 m. They were built with wooden posts and walls made of woven branches covered with mud. Large, bell-shaped pits were used for storage. These pits were probably used to store grain, showing that people produced a lot of extra food.

Pile Dwellings

On lakes in southern Germany and Switzerland, many pile dwellings were built. These were houses constructed on stilts over water. They were made of simple woven branches and mud, or from logs. The settlement at Zug, Switzerland, was destroyed by fire. This gives us important clues about the objects and organization of the time.

-

Biskupin fortified settlement reconstruction, Poland

Urnfield Tools and Art

Pottery and Vessels

Urnfield pottery was usually well-made with smooth surfaces. Many pots had a sharp angle in their shape. Some pottery designs copied metal objects. Pots with two cone shapes joined together and a tall neck were very common. There was some carved decoration, but much of the surface was left plain. Pottery kilns (ovens for firing clay) were known, which helped make the pots look even.

Other vessels included cups made of thin bronze sheets with handles. Large bronze cauldrons with cross-shaped handles were also used. Wooden vessels have been found in wet areas, showing they were likely common too.

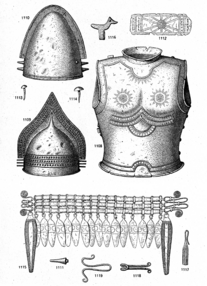

Weapons and Armor

Around 1300 BC, warriors in central Europe could have heavy bronze armor. This included body armor, helmets, and shields. They likely got this idea from Mycenaean Greece.

The Urnfield sword was shaped like a leaf. It was good for slashing, unlike the earlier Tumulus culture swords which were mainly for stabbing. These swords usually had a bronze hilt (handle).

Protective gear like shields, cuirasses (chest armor), greaves (leg armor), and helmets are rare. They are almost never found in burials. A well-known bronze shield from Bohemia has a handle with rivets. Similar shields have been found in Germany, Poland, Denmark, and Britain.

Chariots and Wagons

About a dozen burials from the early Urnfield period include four-wheeled wagons with bronze parts. These wagons were sometimes placed on the funeral pyre. Bronze horse bits also appeared around this time.

Miniature bronze wagons carrying large cauldrons have been found. One very rich burial in Bohemia included a miniature wagon with a cauldron. These wagons are also known from the Nordic Bronze Age.

Bronze wheels with spokes from Germany are considered amazing examples of Bronze Age craftsmanship. They show how skilled these metalworkers were.

Hoards (Hidden Treasures)

Hoards, which are collections of objects hidden away, are very common in the Urnfield culture. This custom stopped at the end of the Bronze Age. Hoards were often placed in rivers and wet places like swamps. Since these spots were hard to reach, they were probably gifts to the gods. Other hoards contain broken metal objects meant to be melted down and reused by bronze smiths.

Early Use of Iron

An iron knife or sickle from Slovakia, possibly from the 18th century BC, might be the earliest sign of smelted iron in Central Europe. Other early iron finds include a ring from Germany (around 15th century BC) and a chisel (around 1000 BC).

During the Late Bronze Age, iron was used to decorate sword handles, knives, and other ornaments. The Carpathian Basin was an early center for iron technology. Iron objects there date back to the 10th century BC, and possibly as early as the 12th century BC. Iron became regularly used for weapons and tools in Central Europe with the later Hallstatt culture.

Urnfield Economy and Daily Life

People in the Urnfield culture raised cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, horses, and dogs. The cattle and horses were quite small.

People cleared a lot of forests during this period. This likely created open meadows for the first time. This also led to more erosion and sediment in rivers. New crops and more intense farming methods changed the landscape a lot.

They grew wheat and barley, along with pulses (like peas and beans). Poppy seeds were used for oil. Millet and oats were grown for the first time in Hungary and Bohemia. Rye was also grown.

People collected hazelnuts, apples, pears, sloes, and acorns. Some rich graves contain bronze sieves. These might have been used for wine, which would have been imported.

Wool was spun into thread and woven into cloth. Bronze needles were used for sewing. Weighing scales were used for trade. Weighed metal was used as a form of payment or money. Bronze sickles are also thought to have been a form of commodity money.

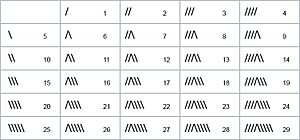

Numbers and Symbols

Large collections of sickles from the Bronze Age have been found in central Europe. Many of these sickles have special marks on them. Studies of these marks suggest they are a number system linked to the lunar calendar.

According to the Halle State Museum of Prehistory: "Many sickles carry line-shaped markings. The scope and order of these brands follows a defined pattern. This sign language can be interpreted as a pre-form of a writing system. There are two types of symbols: line-shaped marks below the button and marks at the angle or at the base of the sickle body. The archaeologist Christoph Sommerfeld examined the rules and realized that the casting marks are composed of one to nine ribs. After four left-hand, individually counted strokes there follows a bundle as a group of five on the right side. This creates a counting system that reaches to 29. The Synodic Moon orbit lasts 29 days or nights. This number and the lunar shape of the sickle suggest that the stroke groups should be interpreted as pages of a calendar, as a point in the monthly cycle. The sickle marks are the oldest known sign system in Central Europe."

The sickles also have other symbols. Some experts think these might be early forms of writing. Similar marks on other tools and pottery have been seen as ownership marks, number systems, or calendar functions.

Simple numbers (lines and dots) are also found on special "ritual objects" from Austria and Sweden. These marks might be instructions for putting the objects together. The decorated discs on these objects are thought to be solar calendars.

Golden Hats

Four amazing cone-shaped hats made from thin sheets of gold have been found in Germany and France. They date from about 1500-800 BC. These hats might have been worn by important "king-priests" or oracles during ceremonies.

The gold hats are covered in patterns and symbols. These symbols are mostly circles, sometimes with wheels, crescents, and triangles. The circles are thought to be sun and moon symbols.

A study of the Berlin Gold Hat found that its symbols are a kind of calendar. It could help predict the movements of the sun and moon. Similar information is thought to be on the other gold hats as well. The Berlin Gold Hat might even have been used to predict lunar eclipses.

The gold hats and other gold objects from this period show that the Urnfield society was complex and had different levels of importance. They also had advanced technical and astronomical knowledge. This suggests that their society was organized around farming and understanding the sky.

Funerary Customs

Graves and Burials

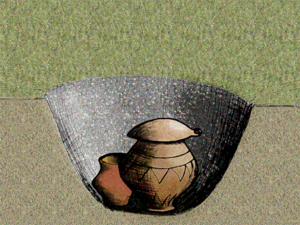

In the earlier Tumulus period, people were often buried whole under mounds of earth. But in the Urnfield period, cremation became common. The ashes were placed in urns and buried in single, flat graves. Some mounds (barrows) still existed, though.

In the earliest Urnfield phase, people dug human-shaped graves. They sometimes lined the bottom with stones. The cremated remains were spread inside. Later, putting the ashes into urns became more popular. Some experts think this change might mean a big shift in what people believed about life and the afterlife.

The size of urnfields varied. Some in Bavaria had hundreds of burials, while others had only about 30. The dead were placed on pyres (bonfires) with their jewelry. The jewelry often shows signs of fire. Sometimes, food was also offered. The bones were often not completely collected.

Most urnfields were no longer used after the Bronze Age. Only the Lower Rhine urnfields continued into the early Iron Age. If bones were placed in urns, these were often covered by a shallow bowl or a stone. Sometimes, the urns were completely covered by a larger, upside-down pot. Graves rarely overlapped, which means they were probably marked with wooden posts or stones.

Grave Gifts

The urn with the ashes was often buried with other smaller ceramic pots, like bowls and cups. These might have held food. These extra pots were usually not burned on the pyre. Metal gifts included razors, weapons (often broken on purpose), bracelets, pendants, and pins. Metal gifts became less common towards the end of the Urnfield culture. At the same time, more hoards (hidden collections of objects) were found.

Burnt animal bones are often found. These might have been food offerings placed on the pyre. Luxury items like Amber or glass beads have also been found.

Upper-Class Burials

Important people were buried in wooden chambers, or sometimes stone chambers. These graves were covered with a barrow (mound of earth) or a cairn (mound of stones). These rich graves contained very fine pottery, animal bones (usually pigs), and sometimes gold rings or sheets. In rare cases, miniature wagons were found.

Some of these rich burials contained the remains of more than one person. In the early Iron Age, burying bodies whole became common again.

Religious Beliefs

There are many pictures and statues of waterbirds from the Urnfield culture. Also, many hoards were placed in rivers and swamps. This suggests that water and waterbirds were important in their religious beliefs. Some experts think this might mean there were serious droughts during the Late Bronze Age.

Sometimes, waterbirds are shown with circles. This is called the sun-barque or solar boat symbol. Moon-shaped clay objects or 'moon idols' are also thought to have religious meaning. Crescent-shaped razors might also be linked to the moon.

Genetics and Ancestry

A study in 2015 looked at the DNA of an Urnfield male buried in Germany around 1100-1000 BC. He had a specific paternal haplogroup called R1a1a1b1a2 and a maternal haplogroup called H23.

Another study in 2019 found that people in Iberia (modern-day Spain and Portugal) had more ancestry from north-central Europe during the change from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. The experts thought that the spread of the Urnfield culture was part of this change. This is when the Celtiberians might have appeared. A Celtiberian male in the study had the paternal haplogroup I2a1a1a.

|

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |