Ancient Celtic religion facts for kids

Ancient Celtic religion, often called Celtic paganism, was the way ancient Celtic people in Europe practiced their faith. We don't have many written records from the Celts themselves about their beliefs. So, what we know comes from old Roman and Greek writings, things found by archaeologists, and stories from early Christian times.

Celtic paganism was one of many religions in Europe during the Iron Age that believed in many gods (polytheism). It changed a bit from place to place and over time, but there were also many similar beliefs across all Celtic groups.

More than 200 names of Celtic gods and goddesses have been found. Some of these might have been different names or titles for the same god, or gods worshipped only in one area. But some gods were known widely. These include Lugus, the tribal god Toutatis, the thunder god Taranis, the horned god Cernunnos, the horse and fertility goddess Epona, and the divine son Maponos. Belenos, Ogmios, and Sucellos were also important. Celtic gods of healing were often linked to special, sacred springs.

The Celts also believed that every part of nature, like trees and rivers, had a spirit. This is called animism.

The druids were the priests of the Celtic religion. We don't know a lot for sure about them. Roman and Greek writers said the Celts held ceremonies in sacred groves (groups of trees) and other natural holy places called nemetons. Some Celtic people also built temples or special enclosed areas for rituals.

Celts often made "votive offerings." These were valuable items they placed in water, wetlands, or in deep shafts and wells as gifts to the gods. There is also proof that ancient Celts sacrificed animals, usually farm animals. Some old Roman and Greek writings even say the Gauls (a Celtic group) sacrificed criminals.

We aren't sure what religious festivals the ancient Celts celebrated. However, the Celtic people in Ireland and Britain celebrated four main seasonal festivals. These were known in medieval Ireland as Beltaine (May 1st), Lughnasadh (August 1st), Samhain (November 1st), and Imbolc (February 1st).

After the Roman Empire took over Gaul (modern France) and southern Britain, Celtic religion there started to mix with Roman religion. This created a new kind of faith called Gallo-Roman religion, with gods like Lenus Mars and Apollo Grannus.

The Gauls slowly became Christians starting in the 200s AD. In Britain and Ireland, Celtic paganism was gradually replaced by Christianity from the 400s AD onwards. But Celtic paganism left its mark on Celtic mythology and even led to new religions in the 1900s, like Celtic neopaganism.

Contents

Celtic Gods and Goddesses

The Celtic religion believed in many gods and goddesses. Some were worshipped only in a small area or by a certain tribe. Others were known and worshipped in many places. As mentioned, over 200 names of Celtic deities have been found. Many of these might have been different names for the same god.

The different Celtic groups seem to have had a father god, who was often a god of the tribe and of the dead. Toutatis was likely one name for him. They also had a mother goddess linked to the land, earth, and fertility. Matrona was probably one name for her. This mother goddess could also be a war goddess, protecting her tribe and land, like Andraste.

There also seems to have been a male sky god, Taranis, linked to thunder, the wheel, and the bull. Gods of skill and craft were important, such as the widely known god Lugus, and the smith god Gobannos. Healing gods were often connected to sacred springs, like Sirona and Borvo. Other gods known in many regions include the horned god Cernunnos, the horse and fertility goddess Epona, the divine son Maponos, and Belenos, Ogmios, and Sucellos. Some gods were seen as having three forms, like the Three Mothers.

Some Roman writers, like Julius Caesar, didn't write down the Celtic names of the gods. Instead, they compared them to Roman gods. Caesar said the most worshipped Gaulish god was Mercury, the Roman god of trade. He also said they worshipped Apollo, Minerva, Mars, and Jupiter. Caesar also wrote that the Gauls believed they all came from a god of the dead and underworld, whom he compared to the Roman god Dis Pater.

Other ancient writers said the Celts worshipped the forces of nature and didn't always imagine their gods as looking like humans.

Irish and Welsh Stories

In old Irish and Welsh stories from the Middle Ages, there are many human-like characters who scholars think might have been based on earlier gods. For example, some characters like Medb or Saint Brigit were probably once seen as divine. However, warriors like Cú Chulainn were more like heroes, somewhere between humans and gods.

These Irish stories seem to show a balance between a male tribal god and a female goddess of the land. They also suggest that the gods were smart, skilled in learning, poets, prophets, storytellers, craftsmen, magicians, healers, and warriors. They had all the qualities the Celtic people admired.

The Celts in Ireland and Britain swore their promises by their tribal gods, and by the land, sea, and sky. They would say things like, "If I break my oath, may the land open to swallow me, the sea rise to drown me, and the sky fall upon me."

Nature Spirits

Some experts believe the Celts worshipped certain trees. Others, like Miranda Aldhouse-Green, think the Celts were animists. This means they believed that all parts of the natural world, like rocks, streams, mountains, and trees, had spirits. They also thought it was possible to talk with these spirits.

Places like rocks, streams, mountains, and trees might have had shrines or offerings dedicated to a god or spirit living there. These would have been local spirits, known and worshipped by people living nearby, not gods known across all Celtic lands. The importance of trees in Celtic religion can be seen in tribe names, like the Eburonian tribe, which refers to the yew tree. Also, names like Mac Cuilinn (son of holly) and Mac Ibar (son of yew) appear in Irish myths. In Ireland, wisdom was symbolized by salmon eating hazelnuts from trees around the well of wisdom.

Few animal figures are found in early Celtic art, but many are water-birds. It's thought that their ability to move in the air, water, and land gave them a special meaning to the Celts.

Burial and the Afterlife

Celtic burial customs, which included burying valuable items like food, weapons, and jewelry with the dead, suggest they believed in life after death.

The druids, who were the learned people among the Celts (including priests), were said by Julius Caesar to believe in reincarnation. This means they thought souls were reborn into new bodies. They also studied astronomy and the nature of the gods.

A common idea in later stories from Christian Celtic nations was the "otherworld." This was a magical place where fairy folk and other supernatural beings lived. They would sometimes invite humans into their world. Sometimes this otherworld was thought to be underground, and other times far to the west. Some scholars think the otherworld was the Celtic afterlife, but there's no direct proof.

Celtic Practices

Holy Places

Evidence shows that Celts made offerings to their gods all over the landscape, both in nature and near their homes. Sometimes they worshipped in built temples and shrines, which archaeologists have found across Celtic lands. But old Roman and Greek writings also say they worshipped in natural places they considered sacred, especially in groves of trees.

Across Celtic Europe, many built temples were square and made of wood. They were often found inside rectangular ditches called viereckschanzen. In places like Holzhausen in Bavaria, offerings were also buried in deep shafts. In Britain and Ireland, temples were more often round. The large religious sites in Ireland, like the Hill of Tara, are especially impressive.

Since groves of trees don't last in the ground, we don't have direct proof of them today. Besides groves, certain springs were also seen as sacred and used for worship. Examples in Gaul include the sanctuary of Sequana at the source of the Seine River and Chamalieres near Clermont-Ferrand. Many offerings, mostly wooden carvings and some metal pieces, have been found at these sites.

Often, when the Roman Empire took over Celtic lands, they built Roman temples on the same sites where Iron Age holy places had been.

Offerings to the Gods

The Celts made votive offerings to their gods. These were buried in the earth or thrown into rivers or bogs. These offerings were often placed in the same spots many times, showing that these places were used continuously, perhaps at certain times of the year or when a special event happened.

Items related to warfare were often offered in watery areas. This was common not only in Celtic regions but also in older societies and in places outside the Celtic area, like Denmark. A famous example is the River Thames in southern England, where many items were found, like the Battersea Shield and the Waterloo Helmet. These were valuable and difficult to make. Another example is Llyn Cerrig Bach in Wales, where battle-related offerings were thrown into the lake.

Sometimes, jewelry and other valuable items not related to war were also offered. For example, at Niederzier in Germany, a post believed to be religious had a bowl buried next to it. Inside were 45 gold coins, two torcs (neck rings), and an armlet. Similar findings have been made elsewhere in Celtic Europe.

Animal Sacrifices

There is proof that ancient Celtic people sacrificed animals, usually farm animals. The idea was likely that giving a life force to the Otherworld pleased the gods and opened a way to communicate with them. Animal sacrifices could be for saying thank you, for making peace, for asking for good health, or for trying to see the future. It seems some animals were given entirely to the gods (by burying or burning), while others were shared between gods and humans.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer from the 1st century AD, wrote about druids performing a ritual. They would sacrifice two white bulls, cut mistletoe from a sacred oak tree with a golden sickle, and use it to make a special drink to help with fertility and to cure poison.

Archaeologists have found that at some Gaulish and British holy sites, horses and cattle were killed and their whole bodies carefully buried. At Gournay-sur-Aronde, the animals were left to decay, and then their bones were buried around the edge of the holy place with many broken weapons. This happened regularly, about every ten years.

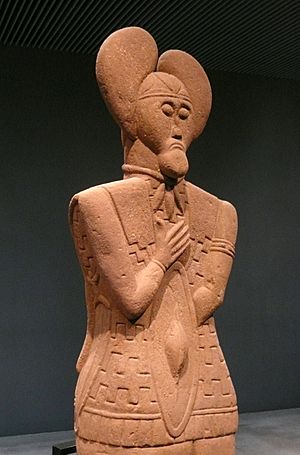

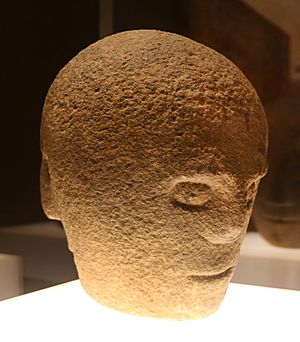

The Head Cult

Many archaeologists and historians believe that images of the human head were very important in Celtic religion. This is sometimes called a "head cult." The Romans and Greeks knew the Celts had a reputation for collecting heads. Greek historians wrote in the 1st century BC that Celtic warriors cut off the heads of enemies killed in battle, hung them from their horses' necks, and then nailed them outside their homes. Another writer, Strabo, said Celts preserved the heads of their most respected enemies in cedar oil and displayed them.

The effort taken to preserve and display heads, and how often severed heads appear in Celtic art, suggests they had a religious meaning. Experts believe the Celts respected the power of the head. Owning and displaying a head was thought to keep and control the power of the dead person. The head was seen as a symbol of divinity and the powers of the otherworld. It was considered the most important body part, the very place where the soul lived. It was also seen as the place of consciousness and wisdom.

Celtic Priests and Poets

Druids

According to several Roman and Greek writers, like Julius Caesar and Pliny the Elder, the Celtic societies in Gaul and Britain highly respected a group of religious experts called druids. Their roles varied a bit in different accounts. Caesar, who wrote the earliest and most complete description, said druids handled "divine worship, sacrifices, and explaining religious questions." He also claimed they were in charge of human sacrifices, like burning people in a wicker man. However, some historians think these accounts might be biased or not fully accurate.

Old Irish writings also mention druids. They are shown not just as priests but as sorcerers with magical powers for cursing and seeing the future. They were also seen as opposing the arrival of Christianity.

Historians and archaeologists have different ideas about druids. Some believe they were like the Brahmin priests in India. Others think they were more like shamans in tribal societies. Some scholars are very doubtful about many claims made about druids, saying we know very little for sure about them.

Poets

In Ireland, the fili were special poets who could see the future. They were known for keeping traditions, writing poems, and remembering many verses. They were also seen as magicians, because Irish magic was closely linked to poetry. A curse from a skilled poet was taken very seriously. In Ireland, a "bard" was a lower rank of poet than a fili, more like a singer and reciter than an inspired artist with magical powers. In Wales, the poet was always called a "bardd."

Celtic poets, no matter their rank, wrote praises and criticisms. A main duty was to write and recite verses about heroes and their brave deeds, and to remember the family histories of their patrons (people who supported them). It was important for their living that they made their patrons famous through stories, poems, and songs. In the 1st century AD, the Roman writer Lucan called "bards" the national poets or singers of Gaul and Britain. In Roman Gaul, this tradition slowly disappeared. But in Ireland and Wales, it continued into the Middle Ages. In Wales, the bardic order was brought back and organized by a poet named Iolo Morganwg. This tradition continues today, especially at the many eisteddfods (festivals of Welsh culture) at all levels of Welsh society.

Old Celtic Calendar

The oldest Celtic calendar we know about is the Coligny calendar, from the 2nd century AD. This was during the time of Roman rule in Gaul.

Some feast days in the medieval Irish calendar are thought to come from older, prehistoric festivals. This is especially true for Beltane, which medieval Irish writers said had ancient origins. The festivals of Samhain and Imbolc are not directly linked to "paganism" or druids in Irish legends. However, since the 1800s, some have suggested they also have a prehistoric background. For example, some thought Samhain marked the "Celtic new year."

Gallo-Roman Religion

The Celtic people in Gaul and Hispania (modern Spain) who were under Roman rule mixed Roman religious practices with their own traditions. Sometimes, Celtic god names were used as titles for Roman gods, like Lenus Mars or Jupiter Poeninus. In other cases, Roman gods were given Celtic female partners. For example, Mercury was paired with Rosmerta, and Sirona with Apollo. In at least one case, a native Celtic goddess, Epona (the horse goddess), was also adopted by the Romans. This way of matching Celtic gods with Roman ones was called Interpretatio romana.

Eastern mystery religions, like the cults of Orpheus, Mithras, Cybele, and Isis, also came to Gaul early on. The worship of the Roman emperor, especially Augustus, became very important in public religion in Gaul. A big ceremony for Rome and Augustus was held on August 1st near Lugdunum.

Generally, Roman worship practices, like offering incense and animal sacrifices, writing dedications, and making realistic statues of gods in human form, were combined with specific Gaulish practices. One Gaulish practice was walking around a temple. This led to a unique Gallo-Roman temple called a fanum, which archaeologists can identify by its round shape.

Becoming Christian

Celtic societies under Roman rule likely became Christian slowly, similar to the rest of the Roman Empire. There is almost nothing in Christian writings about specific issues related to Celtic people in the Empire or their religion. Saint Paul's letter to the Galatians was written to a group that might have included people from a Celtic background.

In Ireland, which was not conquered by the Romans, the change to Christianity from the 400s AD onwards greatly affected the religious system. By the early 600s, the church had pushed Irish druids aside. However, the filidh, who were masters of traditional learning, worked well with Christian clergy. They managed to keep a lot of their pre-Christian traditions, social status, and privileges. But almost all the old Irish stories that survived were written down in monasteries. So, modern scholars try to figure out how much of these texts came from old traditions and how much was added by the church.

Cormac's Glossary (around 900 AD) says that Saint Patrick stopped the filidh's magical rituals that involved offerings to "demons." The church also worked hard to stop animal sacrifices and other rituals they found unacceptable. What survived of ancient rituals tended to be related to filidhecht (the traditional knowledge of the filidh) or to the important idea of sacred kingship.

Old Traditions That Lived On

Some experts have noted that Gaelic oral traditions (stories passed down by word of mouth) have been very well preserved. Tales told in the 1800s were almost exactly the same as those in ancient manuscripts. This suggests that much of what the monks wrote down was much older. Even though Christian additions are clear in some tales, they often seem like afterthoughts. The main parts of the stories likely preserve traditions much older than the manuscripts themselves.

Stories based on (but not exactly the same as) pre-Christian traditions were still common knowledge in Celtic-speaking cultures in the 1800s. During the Celtic Revival, these traditions were collected and written down, becoming a literary tradition. This then influenced modern ideas of "Celticity." Several Celtic celebrations have been practiced in some form since ancient times, such as the Beltane festival and the Puck Fair in Killorglin, which seems to be a survival of Lughnasadh.

Various rituals involving trips to places like hills and sacred wells, believed to have healing or other good properties, are still performed. These include the tradition of clootie wells in Scotland, Ireland, and Cornwall, and the practice of well dressing in the English Midlands. The same applies to wish trees, which are part of the clootie well tradition. Based on evidence from mainland Europe, various figures still known in folklore in Celtic countries today, or who appear in post-Christian stories, were also worshipped in areas that had no records before Christianity. On the Inishkea Islands off the west coast of Ireland, Celtic pagan rituals were seemingly performed well into the 1800s.

Other possible remnants of Celtic paganism include the Irish strawboy tradition and Wren Day traditions, as well as the Shetlandic practice of Skekling. All of these involve dressing in unusual costumes made of straw.

In their book Twilight of the Celtic Gods (1996), Clarke and Roberts describe some very old folk traditions in remote rural areas of Great Britain, like the Peak District and Yorkshire Dales. These include claims of surviving pre-Christian Celtic traditions of worshipping stones, trees, and bodies of water.

New Celtic Paganism

Various modern pagan groups say they are connected to Celtic paganism. These groups range from "Reconstructionists," who try to practice ancient Celtic religion as accurately as possible, to new age groups who get some of their ideas from Celtic mythology and symbols. The most well-known of these is Neo-druidry.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Politeísmo celta para niños

In Spanish: Politeísmo celta para niños

- Proto-Celtic folklore

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |