Battle of Cynoscephalae facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Cynoscephalae |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Macedonian War | |||||||

A map showing the location of Cynoscephalae |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic Aetolian League |

Macedonia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Titus Quinctius Flamininus Amynander of Athamania |

Philip V (king) Heracleides of Gyrton Athenagoras of Macedon Nicanor the Elephant |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

c. 26,000 21,600 infantry 1,300 cavalry 3,000 marines 20 war elephants |

25,500 16,000 phalangites 2,000 light infantry 5,500 mercenaries and allies 2,000 cavalry |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 700 killed |

13,000 8,000 killed 5,000 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Cynoscephalae was a major battle fought in 197 BC. It took place in Thessaly, a region in ancient Greece. The battle was between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the army of Macedonia, led by King Philip V. This battle was a big win for the Romans and ended the Second Macedonian War.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The First Macedonian War had ended in a draw. Macedonia had teamed up with Carthage against Rome. This made the Romans very angry. Even though the war ended, Rome still didn't trust Macedonia.

Later, in 202 BC, King Philip V of Macedonia made a deal with the Seleucid Empire. They planned to divide up parts of Asia Minor. Philip also started taking over cities in Thrace and near the Dardanelles. This worried other Greek states like Rhodes and the Kingdom of Pergamum.

Rhodes and Pergamum fought Philip and even defeated his navy. But they were still concerned about Macedonia's growing power. So, they asked Rome for help. Rome sent its own messengers to Greece to form a group against Philip. Philip thought Rome was weak because they had just finished another big war. He kept trying to conquer more land. Because of this, the Roman Senate and Assembly declared war on Macedonia. This started the Second Macedonian War.

In 198 BC, a new Roman commander, Titus Quinctius Flamininus, took charge. He met with Philip to talk about peace. Flamininus demanded that Philip remove all his soldiers from Greece, except for his homeland. Philip refused and left the meeting. Flamininus then began his military campaign.

By early 197 BC, Philip had lost most of his new lands. He was pushed back to Macedonia and parts of Thessaly. Flamininus brought his army to Thessaly, and Philip marched south to meet him. They first had small fights near the city of Pherae. Philip's army needed food and flat ground for his soldiers, called phalangites, to fight properly. So, he moved his army west towards a town called Scotussa to get grain. The Romans followed them. Both armies marched on different sides of the Cynoscephalae Hills.

The Armies

Roman Army

Flamininus had about 26,000 soldiers. This included two full Roman legions. He also had support from 6,000 foot soldiers and 400 horsemen from the Aetolian League. An extra 1,200 men came from Amynander of Athamania. The Romans also had 20 war elephants from Numidia. More soldiers from Italy brought Flamininus an additional 6,000 foot soldiers, 300 horsemen, and 3,000 marines.

Macedonian Army

Philip had about 25,500 soldiers. Of these, 16,000 were phalangites. These were soldiers who fought in a tight formation called a phalanx, using very long spears called sarissas. Many of these soldiers were very young or very old because Macedonia had been fighting many wars.

Philip also had 2,000 peltasts (light foot soldiers). He had 4,000 men from the Thracians and Trallians, 1,500 mercenaries, and 2,000 horsemen.

Philip's cavalry was led by Heracleides of Gyrton and Leon. The mercenaries were commanded by Athenagoras of Macedon. The second group of foot soldiers was led by Nicanor the Elephant.

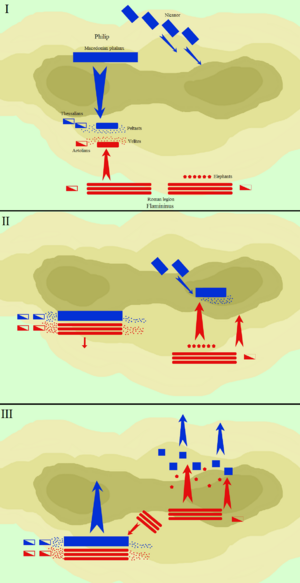

The Battle

During their march, there was a heavy rainstorm. The next morning, a thick fog covered the hills and fields between the two armies. Philip's army desperately needed supplies, so he kept marching. But his soldiers became confused in the fog. Philip decided to set up camp instead. He sent half of his heavy foot soldiers to find food. He also sent his light foot soldiers and half of his horsemen to take the Cynoscephalae Hills and find the Roman army.

Flamininus didn't know where Philip's army was either. He sent 1,000 light foot soldiers and 300 horsemen to find them. These Roman soldiers met Philip's troops on the hills.

In the thick fog, the light foot soldiers from both sides bumped into each other. They fought hand-to-hand because they couldn't see well. Then, the horsemen joined the fight. The Romans were slowly being pushed back because Philip had more soldiers. The Roman force asked Flamininus for help.

Flamininus sent 2,000 more light foot soldiers and 500 horsemen. He sent only a few because the fog still covered the battlefield. He couldn't send his whole army until he knew how many Macedonians were there. Even with limited numbers, these Roman reinforcements helped. The Macedonians were pushed back to the top of the Cynoscephalae Hills.

Philip received reports that the Romans were retreating. He thought his soldiers had defeated the entire Roman army. Philip didn't want to send his phalanx into the broken, hilly ground. But because of the good reports, he ordered 8,000 phalangites and 4,000 peltasts to attack. He told Nicanor to get the rest of the phalangites ready to help as soon as possible.

When Flamininus saw such a large force in front of his camp, he led the rest of his army out. He formed them into a battle line. He placed his war elephants at the front of his right side. The Roman legions were organized in flexible units called maniples. This allowed the retreating Romans to escape the Macedonians. The Macedonians then fell back when they saw the Roman battle lines forming. Flamininus commanded from his left legion and moved forward with it. He kept his right side ready as a reserve.

Philip now realized the reports were wrong. He arrived just as his soldiers were retreating back up the hill. He knew that trying to retreat would be a disaster. So, Philip gathered his retreating troops at the top of the ridge. He formed them on the right side of his army. He put the peltasts to the left of his horsemen, and his phalangites to the left of the peltasts. He formed a peltast line 16 men deep and a phalangite line 36 men deep. Philip couldn't wait for Nicanor to arrive. He sent his right phalanx into the Roman left side, pushing them down the ridge, but slowly.

While this was happening, the Macedonian left side, led by Nicanor, was arriving in small groups at the top of the ridge. Flamininus saw Nicanor's disorganized troops. He rode to his right side and ordered them to attack. His elephants led the way, followed by the rest of his forces, their Italian allies, and 4,000 Greek foot soldiers. The Macedonian soldiers were still marching in columns or struggling to get up the hills. The war elephants crashed into the disorganized Macedonian left, scattering them. The Romans chased them down the hill.

As the Romans were chasing, a Roman officer saw that the Macedonian right side was exposed from behind. He took 20 maniples (about 2,500 foot soldiers) and sent them to attack the back of the Macedonian phalanx. The phalanx was very strong from the front but not flexible. It couldn't turn around quickly. So, the Macedonian phalanx quickly broke apart. Some soldiers were killed where they stood. Others pointed their long spears upwards as a sign of surrender. But the Romans either didn't understand or ignored this. The killing continued until Flamininus stopped it.

Philip, with a few horsemen, had gone to the top of the hill to get a better view of the battle. He saw his right side collapsing and his left side running away. He then fled the battle with his guards and returned to Macedonian land. The ancient writer Plutarch said:

Philip, however, got safely away, and for this the Aetolians were to blame, who fell to sacking and plundering the enemy's camp while the Romans were still pursuing, so that when the Romans came back to it they found nothing there.

Aftermath

According to ancient writers Polybius and Livy, 8,000 Macedonian soldiers were killed. Flamininus also captured 5,000 prisoners. The Romans lost only about 750 men in the battle.

This battle, along with the later Battle of Pydna, showed that the Roman legion was better than the Macedonian phalanx. The phalanx was very strong when attacking head-on. But it was not as flexible as the Roman manipular formation. This meant it couldn't easily change direction or break away from a fight if needed. Some people argue that the Romans won because the Macedonian left side was not fully formed. But this also shows how difficult the phalanx was to control compared to the Roman legion.

The Battle of Cynoscephalae was a huge defeat for Macedonia. It meant that Macedonia could no longer challenge Rome's growing power. The peace treaty in 196 BC allowed Philip to keep his kingdom. But he had to agree to several strict rules:

- He had to give up all the lands he had recently conquered. He had to return to the original borders of Macedonia.

- He had to remove all his soldiers from outside Macedonia. This was to make those nations free and independent.

- He had to pay Rome a large amount of silver, 1,000 talents. Half was paid right away, and the rest in yearly payments.

- He had to give up almost all of his warships.

- He could only have an army of 5,000 soldiers, and no elephants.

- He could not start wars outside Macedonia without Rome's permission.

Plutarch also said that Rome took one of Philip's sons, Demetrius, as a hostage.

...and taking one of his sons, Demetrius, to serve as hostage, sent him off to Rome, thus providing in the best manner for the present and anticipating the future

However, Demetrius was released five years later. This was because Macedonia helped Rome during a war against the Seleucids.

And apart from this money Philip owed his fine of a thousand talents.This fine, however, the Romans were afterwards persuaded to remit to Philip, and this was chiefly due to the efforts of Titus; they also made Philip their ally, and sent back his son whom they held as hostage.

At the Isthmian Games in 196 BC, Flamininus announced that all Greek states previously controlled by Philip were now free.

Images for kids