History of Macedonia (ancient kingdom) facts for kids

The ancient Kingdom of Macedonia was a powerful state in what is now northern Greece. It began around the mid-7th century BC and lasted until the mid-2nd century BC.

At first, the Argead family ruled Macedonia. It became a state controlled by the mighty Persian Empire during the reigns of King Amyntas I (547–498 BC) and his son King Alexander I (498–454 BC). This period ended around 479 BC when the Greeks finally defeated the Persians and forced them out of Europe.

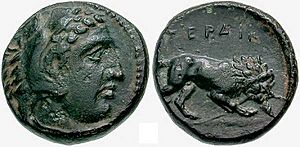

During the time of Classical Greece, King Perdiccas II (454–413 BC) got involved in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC). This was a big war between Athens and Sparta. Perdiccas kept changing sides to keep Macedonia in control of the Chalcidice area. His rule also saw fights and temporary friendships with Sitalces, the Thracian ruler. Eventually, Perdiccas made peace with Athens.

His son, King Archelaus I (413–399 BC), brought peace and wealth to Macedonia. But his death was a mystery and left the kingdom in trouble. The next period was very difficult, with invasions from the Illyrians and the city of Olynthos. King Amyntas III (393–370 BC) managed to defeat these enemies with help from other Greek states.

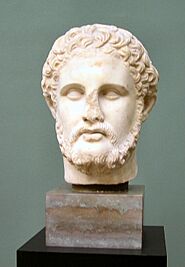

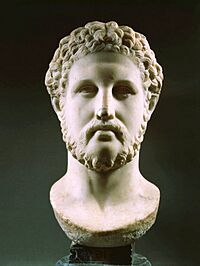

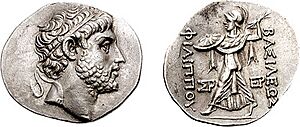

King Philip II (359–336 BC) came to power after his older brother, King Perdiccas III (368–359 BC), was killed in battle. Philip was very smart and used diplomacy to make peace with his neighbors: the Illyrians, Thracians, Paeonians, and Athenians. This gave him time to make huge changes to the Macedonian army. He created the famous Macedonian phalanx, a powerful fighting formation with long spears. This army helped Macedonia conquer most of Greece, except for Sparta.

Philip II also grew his power by marrying princesses from other lands to form alliances. He destroyed the Chalcidian League and became an important member of the Thessalian and Amphictyonic Leagues after helping defeat Phocis in the Third Sacred War. After Macedonia won the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC against Athens and Thebes, Philip created the League of Corinth. He was chosen as its leader, planning to lead a united Greek invasion of the Persian Empire.

However, Philip II was assassinated by one of his bodyguards. His son, Alexander III, known as Alexander the Great (336–323 BC), took over. Alexander invaded Egypt and Asia, overthrowing the Persian king Darius III. Alexander died at age 32 from an unknown illness. After his death, his generals, called the diadochi, divided his vast empire. This began the Hellenistic period, leading to the creation of new kingdoms like the Ptolemaic, Seleucid, and Attalid empires.

Macedonia remained a strong state in Hellenistic Greece, but its power decreased due to civil wars between different ruling families. Despite invasions from powerful leaders like Pyrrhus of Epirus and the Celtic Galatians, King Antigonus II (277–274 BC; 272–239 BC) managed to control Athens and defend against Egypt's navy. However, a rebellion led by Aratus of Sicyon in 251 BC created the Achaean League, which often challenged Macedonian power in Greece.

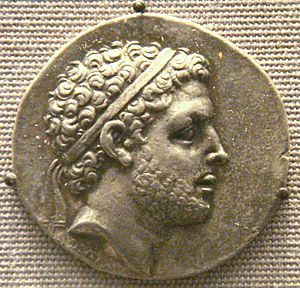

Macedonian power grew again under King Antigonus III Doson (229–221 BC), who defeated the Spartans. King Philip V (221–179 BC) also won against the Aetolian League. But his attempts to expand into the Adriatic Sea and his alliance with Hannibal of Carthage worried the Roman Republic. Rome convinced other Greek states to attack Macedonia while Rome fought Hannibal. Rome won the First (214–205 BC) and Second Macedonian Wars (200–197 BC) against Philip V. Macedonia lost its lands in Greece. The Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) ended the Macedonian monarchy completely. Rome then set up four smaller republics in Macedonia. A man named Andriscus briefly brought back the monarchy during the Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC), but his forces were crushed by the Romans. This led to Macedonia becoming a Roman province.

Contents

Early History and Legends

Ancient Greek historians like Herodotus and Thucydides wrote about the legend that the Macedonian kings came from Temenus of Argos. Temenus was believed to be a descendant of the mythical hero Heracles. The story says that three brothers from Temenus's family traveled from Illyria to Upper Macedonia. A local king almost killed them because an omen said the youngest, Perdiccas, would become king. Perdiccas eventually became king after settling near the gardens of Midas in Lower Macedonia.

Other historians mentioned Caranus of Macedon as the first king, followed by Perdiccas I. Greeks in the Classical period generally accepted the story from Herodotus. This idea, or another linking them to Zeus, the chief Greek god, made people believe the Macedonian kings had a divine right to rule. Herodotus wrote that King Alexander I (498–454 BC) convinced the judges of the Ancient Olympic Games that his family line went back to Temenus. This Greek heritage allowed him to compete in the Olympics.

We know very little about the first five Macedonian kings. There is more information about King Amyntas I (547–498 BC) and his son Alexander I. This is partly because Alexander I helped the Persian commander Mardonius during the Greco-Persian Wars. Historian Robert Malcolm Errington estimates that the capital city, Aigai (modern Vergina), might have been ruled by these kings since the mid-7th century BC.

The kingdom was in a rich, flat area called Lower Macedonia, north of Mount Olympus. Rivers like the Haliacmon and Axius (Vardar) flowed through it. Around the time of Alexander I, the Macedonians began to expand into Upper Macedonia. This area was home to independent Greek tribes. They also moved west of the Axius river into other regions.

To the north of Macedonia lived non-Greek peoples like the Paeonians, Thracians, and Illyrians. Macedonians often fought with the Illyrians. To the south was Thessaly, whose people shared much with the Macedonians. To the west was Epirus, with whom Macedonians had peaceful relations and even formed an alliance against Illyrian raids in the 4th century BC. Before the 4th century BC, the kingdom covered parts of what is now western and central Macedonia in modern Greece.

In 513 BC, the Persian king Darius I launched a military campaign in Europe. His general Megabazus stayed behind to control the Paeonians, Thracians, and Greek cities along the coast. Around 512/511 BC, Megabazus demanded that Macedonia become a vassal state of the Persian Empire. King Amyntas I agreed, starting the period of Achaemenid Macedonia, which lasted about 30 years. Macedonia was mostly independent but had to provide soldiers and supplies for the Persian army.

Persian control was interrupted by the Ionian Revolt (499–493 BC). But the Persian general Mardonius brought Macedonia back under Persian rule. It's unlikely Macedonia was ever an official Persian province. King Alexander I probably saw this as a chance to expand his own kingdom, using Persian military support. Macedonians helped the Persian king Xerxes I during the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480–479 BC. After the Greek victory at Salamis, the Persians sent Alexander I to Athens to try and form an alliance, but Athens refused. Persian control over Macedonia ended when the Greeks finally defeated the Persians and they left Europe.

Macedonia in Classical Greece

King Alexander I, who was called a "friend of the Greeks" by the Athenians, built strong ties with the Greeks after the Persian defeat. He sponsored statues at important Greek religious sites like Delphi and Olympia. After his death in 454 BC, he was given the title Alexander I 'the Philhellene' (friend of the Greeks).

His successor, King Perdiccas II (454–413 BC), faced internal revolts and threats from Thracian ruler Sitalces and the Athenians. Athens fought four separate wars against Macedonia under Perdiccas II. From 476 BC, Athenians started settling in coastal Macedonia to get timber and other resources for their navy. In 437/436 BC, Athens founded the city of Amphipolis near the Strymon River to access timber, gold, and silver.

War broke out in 433 BC when Athens allied with Perdiccas II's rebellious relatives. Perdiccas tried to ally with Sparta and Corinth, Athens' rivals. When that failed, he encouraged nearby Athenian allies in Chalcidice to revolt, winning over the important city of Potidaea. Athens sent a naval force that captured Therma and besieged Pydna. However, Athens couldn't retake Chalcidice and Potidaea because their forces were spread too thin. They made peace with Macedonia.

War soon started again, but by 431 BC, Athens and Macedonia made a peace treaty and alliance. This was arranged by the Thracian ruler Sitalces. Perdiccas II got Therma back and no longer had to fight his rebellious brother, Athens, and Sitalces all at once. In return, he helped Athens control settlements in Chalcidice.

In 429 BC, Perdiccas II sent help to the Spartan commander Cnemus, but the Macedonian forces arrived too late. That same year, Sitalces invaded Macedonia, supposedly to help Athens. However, Sitalces had a huge army (150,000 soldiers) and planned to put Perdiccas II's nephew on the throne. Athens seemed worried and didn't send the promised naval support. Sitalces eventually left Macedonia, possibly due to lack of supplies and harsh winter weather.

In 424 BC, Perdiccas helped the Spartan general Brasidas convince Athenian allies in Thrace to switch sides and join Sparta. Perdiccas also helped Brasidas fight against Arrhabaeus of Lynkestis, a region in Upper Macedonia. However, the Macedonian army fled before the battle began, making the Spartans angry. Perdiccas then made peace with Athens and switched sides again. He blocked Spartan reinforcements from reaching Brasidas. This treaty gave Athens economic benefits and brought stability to Macedonia.

Perdiccas II had to send help to the Athenian general Cleon. But both Cleon and Brasidas died in 422 BC. The Peace of Nicias, signed between Athens and Sparta the next year, ended Perdiccas's duties as an Athenian ally. After a battle in 418 BC, Sparta and Argos formed a new alliance. This, along with threats from pro-Spartan cities in Chalcidice, made Perdiccas II abandon his Athenian alliance for Sparta again. This was a mistake, as Argos quickly became pro-Athenian. Athens punished Macedonia with a naval blockade in 417 BC. Perdiccas II agreed to peace and an alliance with Athens again in 414 BC. He died a year later, and his son King Archelaus I (413–399 BC) took over.

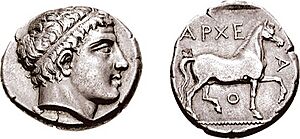

King Archelaus I kept good relations with Athens. He relied on Athens for naval support in his siege of Pydna in 410 BC, and in return, he provided Athens with timber and naval equipment. Archelaus improved the military and built new forts, making Macedonia stronger. He also expanded his power into Thessaly. He moved the capital from Aigai to Pella, which was by a lake connected to the Aegean Sea. He also improved Macedonia's money by making coins with more silver and issuing copper coins. His royal court attracted famous thinkers like the Athenian writer Euripides.

After Archelaus I's death, there was a struggle for power from 399 to 393 BC, with four different kings claiming the throne. Very little is known about this time. Finally, King Amyntas III (393–370 BC) took the throne.

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote about Illyrian invasions in 393 BC and 383 BC, possibly referring to one large invasion led by Bardylis. Amyntas III reportedly fled his kingdom but returned with help from Thessalian allies. The powerful city of Olynthos then threatened to conquer Macedonia. Sparta sent a large force to help Amyntas III. This campaign ended in 379 BC with Olynthos surrendering and the Chalcidian League being dissolved.

Amyntas III had children with two wives. His eldest son with Eurydice I, Alexander II (370–368 BC), became king. When Alexander II invaded Thessaly, the Thessalians asked Pelopidas of Thebes for help. Pelopidas captured Larissa, and Alexander II made peace with Thebes. As part of the deal, he gave noble hostages, including his younger brother, the future King Philip II. Later, Ptolemy of Aloros assassinated Alexander II and became regent for Perdiccas III (368–359 BC). Ptolemy's actions in Thessaly led to another Theban invasion. By 365 BC, Perdiccas III was old enough to rule and killed Ptolemy. His reign brought stability and financial recovery. However, Perdiccas III also faced an Athenian invasion and was killed in battle by Illyrians led by Bardylis.

The Rise of Macedon

King Philip II (359–336 BC) was 24 when he became king. He had spent much of his youth as a hostage in Thebes. He immediately faced challenges, but he used clever diplomacy. He bribed the Thracians and Paeonians to stop supporting a pretender to the throne. He also made a treaty with Athens, giving up his claims to Amphipolis. He also made peace with the Illyrians.

The exact date when Philip II began to change the Macedonian army is not known. These changes included new organization, equipment, and training, especially the creation of the Macedonian phalanx with its long spears called sarissas. These reforms took several years and were very successful against his enemies. Philip's time as a hostage in Thebes, where he met the famous general Epaminondas, likely influenced his ideas for military reform.

Unlike most Greeks, Philip II had multiple wives. He married seven different women, often to gain the loyalty of his nobles or to form new alliances. For example, he married Phila of Elimeia from the Upper Macedonian nobility and the Illyrian princess Audata to secure alliances. In 358 BC, he married Philinna to ally with Larissa in Thessaly. In 357 BC, he married Olympias to secure an alliance with Epirus. Olympias later gave birth to Alexander the Great. Philip also had some of his half-brothers killed or exiled, which led to the Olynthian War (349–348 BC).

While Athens was busy with another war, Philip took the chance to retake Amphipolis in 357 BC. Athens then declared war on him. By 356 BC, he captured Pydna and Potidaea. He gave Potidaea to the Chalcidian League as promised. That same year, he took Crenides, which he renamed Philippi. This city brought him much gold. His general Parmenion also defeated the Illyrian king Grabos II. During the siege of Methone (355–354 BC), Philip lost his right eye to an arrow, but he captured the city and was kind to its people.

Philip II then got Macedonia involved in the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC). This war started when Phocis took treasures from the temple of Apollo at Delphi. Philip's first campaign against Pherae in Thessaly in 353 BC ended in two defeats. However, he returned the next year and won a major battle. This led to him being chosen as leader of the Thessalian League and gaining a seat on the Amphictyonic Council.

After fighting the Thracian ruler Cersobleptes, Philip II started a war against the Chalcidian League in 349 BC. Despite Athens sending help, Philip II captured Olynthos in 348 BC and sold its people into slavery, including some Athenians. The Athenians tried to get their allies to fight back, but they failed. So, in 346 BC, Athens made a treaty with Macedonia called the Peace of Philocrates. Athens gave up its claims to Macedonian coastal lands and Amphipolis. In return, Philip released enslaved Athenians and promised not to attack Athenian settlements. Meanwhile, Phocis was captured, and Philip II was given two seats on the Amphictyonic Council. Athens initially protested but eventually accepted these terms.

For the next few years, Philip II reorganized Thessaly, fought the Illyrian ruler Pleuratus I, and defeated Cersebleptes in Thrace. This allowed him to control the Hellespont, preparing for an invasion of the Persian Empire. In what is now Bulgaria, Philip II conquered the Thracian city of Panegyreis in 342 BC and renamed it Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv).

War broke out with Athens again in 340 BC. Philip II was busy with two unsuccessful sieges of Perinthus and Byzantion. He then had a successful campaign against the Scythians along the Danube. Macedonia also got involved in the Fourth Sacred War in 339 BC. Hostilities between Thebes and Macedonia began when Thebes removed a Macedonian garrison. Thebes then joined Athens, Megara, Corinth, Achaea, and Euboea in a final battle against Macedonia at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC. Macedonia won this battle.

After the victory at Chaeronea, Philip II imposed harsh terms on Thebes but was lenient with Athens. He wanted to use Athens' navy for his planned invasion of the Persian Empire. He then formed the League of Corinth, which included most major Greek city-states except Sparta. Philip was elected as its leader in 337 BC, planning to command a united Greek army against Persia. The fear of another Persian invasion of Greece likely contributed to Philip II's decision to invade the Persian Empire.

Philip II tried to gain more Macedonian support by marrying Cleopatra Eurydice, the niece of his general Attalus. However, talk of new heirs angered Philip II's son Alexander (who was already a veteran of the Battle of Chaeronea) and his mother Olympias. They fled to Epirus before Alexander was called back. More tensions arose when Philip II offered his son Arrhidaeus's hand in marriage to Ada of Caria, a Persian princess. When Alexander intervened and proposed to marry Ada instead, Philip canceled the wedding and exiled Alexander's advisors. To make up with Olympias, Philip II had their daughter Cleopatra marry Olympias's brother. However, Philip II was assassinated by his bodyguard Pausanias of Orestis during their wedding feast. His son Alexander succeeded him.

The Empire of Alexander the Great

Before Philip II was assassinated in 336 BC, his relationship with his son Alexander had worsened. Philip had planned for Alexander to be regent of Greece and deputy leader of the League of Corinth, not to join the invasion of Asia. Alexander III (336–323 BC) was immediately declared king by the army and leading nobles. By the end of his rule in 323 BC, Alexander would control an empire that included Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and parts of Central and South Asia.

His first tasks were to bury his father and put down rebellions in the Balkans. After Philip's death, the League of Corinth revolted. Alexander quickly put down the revolt with military force and diplomacy, forcing them to rejoin the league and electing him as their leader for the Persian invasion. Alexander also had his rival Attalus executed.

In 335 BC, Alexander led a campaign against the Triballi tribe in the Balkans, fighting them along the Danube River. Soon after, the Illyrian king Cleitus threatened Macedonia. Alexander attacked first and besieged them at Pelion. When Alexander heard that Thebes had revolted again, he marched to Thebes and besieged the city. After breaking through the walls, Alexander's forces killed 6,000 Thebans, took 30,000 as prisoners, and burned the city to the ground. This served as a warning, and no other Greek state dared to challenge Alexander again, except Sparta.

Alexander won every battle he personally led. His first victory against the Persians in Asia Minor was at the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BC. He used a small cavalry group to distract the Persians, allowing his infantry to cross the river. His Companion cavalry then drove the Persians away. At the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, Alexander personally led the cavalry charge, forcing the Persian king Darius III and his army to flee. Darius III, despite having more soldiers, was again forced to flee at the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC. The Persian king was later captured and executed by his own relative, Bessus, in 330 BC. Alexander then hunted down and executed Bessus in Afghanistan.

At the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC (modern-day Punjab), King Porus's war elephants threatened Alexander's troops. Alexander had his men form open ranks to surround the elephants and use their long spears to dislodge their handlers. When his Macedonian troops threatened to mutiny in Babylonia in 324 BC, Alexander offered military titles to Persian officers instead. This forced his troops to seek forgiveness, which Alexander granted at a banquet, urging reconciliation between Persians and Macedonians.

Despite his skills as a commander, Alexander showed signs of wanting too much power. He used propaganda, like cutting the Gordian Knot. He also tried to present himself as a living god and son of Zeus after visiting an oracle in Egypt in 331 BC. When he tried to make his men bow down to him in a Persian custom called proskynesis, the Macedonians and other Greeks saw this as disrespectful to the gods. Alexander's historian Callisthenes refused, and others followed his example, leading Alexander to stop the practice. Alexander also had his general Parmenion murdered in 330 BC, which showed a growing gap between the king's interests and those of his people. His murder of Cleitus the Black in 328 BC is described as "vengeful and reckless." Alexander also continued his father's practice of having multiple wives and encouraged his men to marry local women in Asia. He married Roxana, a Sogdian princess, and later married two Persian princesses at the Susa weddings in 324 BC.

Meanwhile, in Greece, the only challenge to Macedonian rule was the Spartan king Agis III, who tried to lead a rebellion. However, he was defeated in 331 BC by Antipater, who was serving as regent of Macedonia while Alexander was away. Antipater's rule was somewhat unpopular in Greece because he exiled people and put Macedonian soldiers in cities. However, in 330 BC, Alexander declared that the tyrannies (harsh rulers) in Greece should be abolished and Greek freedom restored.

When Alexander the Great died in Babylon in 323 BC, his mother Olympias accused Antipater of poisoning him, but there is no proof. With no clear heir, the Macedonian military leaders were split. Some wanted Alexander's half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus (323–317 BC) as king, while others supported Alexander's infant son with Roxana, Alexander IV (323–309 BC). The Greeks also immediately rebelled against Antipater in a conflict known as the Lamian War (323–322 BC). Antipater eventually put down the rebellion, but he died in 319 BC. This left a power vacuum, and the two young kings became pawns in a struggle between the diadochi, Alexander's former generals who were now dividing his empire.

A council of the army met after Alexander's death and named Philip III as king and Perdiccas as his regent. However, Antipater, Antigonus, Craterus, and Ptolemy formed an alliance against Perdiccas. When Perdiccas invaded Egypt in 321 BC, his men drowned in the Nile River, and his officers assassinated him. The victorious generals then met in Syria to decide on a new regent and territories. They appointed Antipater as regent over the two kings.

Before Antipater died in 319 BC, he named Polyperchon as his successor, passing over his own son Cassander. Cassander then allied with Ptolemy, Antigonus, and Lysimachus. Cassander's officer captured the fortress of Piraeus in Athens, defying Polyperchon's order that Greek cities should be free of Macedonian soldiers. This started the Second War of the Diadochi (319–315 BC).

After Polyperchon's military failures, Philip III, influenced by his wife Eurydice II, officially replaced him as regent with Cassander in 317 BC. Polyperchon then sought help from Olympias, Alexander III's mother, who was in Epirus. A combined force invaded Macedonia and forced Philip III and Eurydice's army to surrender. Olympias then had the king executed. Olympias also had many Macedonian nobles killed. However, by 316 BC, Cassander defeated her forces, captured her, and had her executed.

Cassander married Philip II's daughter Thessalonike, linking him to the royal family. He briefly expanded Macedonian control into Illyria. By 316 BC, Antigonus had taken territory from Eumenes and driven Seleucus Nicator from Babylonia. In response, Cassander, Ptolemy, and Lysimachus demanded that Antigonus surrender various territories. Antigonus allied with Polyperchon and demanded that Cassander hand over the royal family, King Alexander IV and his mother Roxana. The conflict lasted until 312/311 BC, when a peace deal recognized Cassander as general of Europe, Antigonus as 'first in Asia,' Ptolemy as general of Egypt, and Lysimachus as general of Thrace. Cassander had Alexander IV and Roxana killed in 311/310 BC. By 306–305 BC, the diadochi declared themselves kings of their own territories.

The Hellenistic Era

The Hellenistic period began with a struggle between two ruling families: the Antipatrid dynasty, led by Cassander (305–297 BC), and the Antigonid dynasty, led by Antigonus I (306–301 BC) and his son, Demetrius I (294–288 BC). In 301 BC, a coalition of Cassander, Ptolemy I of Egypt, Seleucus I of the Seleucid Empire, and Lysimachus of Thrace decisively defeated the Antigonids at the Battle of Ipsus. Antigonus was killed, and Demetrius fled.

Cassander died in 297 BC, and his son Philip IV died the same year. Cassander's other sons, Alexander V (297–294 BC) and Antipater II (297–294 BC), took over, with their mother Thessalonike as regent. Antipater II killed his own mother to gain power. His brother Alexander V asked for help from Pyrrhus of Epirus (297–272 BC). Pyrrhus was given parts of Macedonia in exchange for defeating Antipater II. Demetrius then marched north, invited his nephew Alexander V to a banquet, and had him assassinated. Demetrius was then proclaimed king of Macedonia.

War broke out between Pyrrhus and Demetrius in 290 BC. By 288 BC, Demetrius lost the support of the Macedonians and fled. Macedonia was then divided between Pyrrhus and Lysimachus. By 286 BC, Lysimachus expelled Pyrrhus from Macedonia. However, in 282 BC, a new war started between Lysimachus and Seleucus I. Lysimachus was killed in battle, allowing Seleucus I to claim both Thrace and Macedonia. But Seleucus I was then assassinated in 281 BC by Ptolemy Keraunos, who became king of Macedonia.

The political chaos continued. Ptolemy Keraunos was killed in battle in 279 BC by Celtic invaders during the Gallic invasion of Greece. The Macedonian army proclaimed the general Sosthenes as king, but he refused the title. The Gallic warbands ravaged Macedonia until Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius's son, defeated them in Thrace in 277 BC. He was then proclaimed King Antigonus II (277–274 BC; 272–239 BC).

Starting in 280 BC, Pyrrhus fought campaigns in southern Italy against the Roman Republic, known as the Pyrrhic War. He also invaded Sicily. Ptolemy Keraunos had helped Pyrrhus by giving him soldiers and war elephants. Pyrrhus returned to Epirus in 275 BC after his campaigns failed. Despite having little money, Pyrrhus decided to invade Macedonia in 274 BC, thinking Antigonus II's rule was weak. Pyrrhus defeated Antigonus II's army and drove him out of Macedonia.

Pyrrhus lost Macedonian support in 273 BC when his Gallic soldiers plundered the royal cemetery of Aigai. Pyrrhus pursued Antigonus II in Greece. While Pyrrhus was busy fighting in the Peloponnese, Antigonus II recaptured Macedonia. Pyrrhus was killed in Argos in 272 BC, allowing Antigonus II to reclaim Greece as well. He then restored the royal tombs at Aigai and secured the northern borders.

Antigonid naval fleets at Corinth and Chalkis helped maintain Antigonid control over various Greek cities. However, the Aetolian League was a constant problem for Antigonus II's control of central Greece. The formation of the Achaean League in 251 BC pushed Macedonian forces out of much of the Peloponnese. Ptolemaic Egypt used its powerful navy to disrupt Antigonus II's efforts in Greece. With Ptolemaic help, the Athenian statesman Chremonides led a revolt against Macedonia called the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC). But by 265 BC, Athens was besieged, and a Ptolemaic fleet was defeated. Athens finally surrendered in 261 BC. After Macedonia allied with the Seleucid ruler Antiochus II, peace was made between Antigonus II and Ptolemy II of Egypt in 255 BC.

However, in 251 BC, Aratus of Sicyon led a rebellion against Antigonus II. In 250 BC, Ptolemy II openly supported Alexander of Corinth, who claimed to be king. Although Alexander died in 246 BC, and Antigonus won a naval victory, the Macedonians lost the Acrocorinth to Aratus's forces in 243 BC. Corinth then joined the Achaean League. Antigonus II finally made peace with the Achaean League in 240 BC, giving up the territories he had lost in Greece.

Antigonus II died in 239 BC, and his son Demetrius II (239–229 BC) succeeded him. Demetrius II married Phthia of Macedon to ally with Epirus, which damaged relations with the Seleucids. Although the Aetolians allied with the Achaean League, Demetrius II invaded Boeotia and captured it from the Aetolians by 236 BC.

Demetrius II's control of Greece weakened by the end of his reign. He lost Megalopolis and most of the Peloponnese to the Achaean League. He also lost Epirus as an ally when its monarchy was overthrown. Demetrius II struggled to defend Acarnania against Aetolia. He even asked for help from the Illyrian king Agron, whose pirates raided Greek coasts and defeated the Aetolian and Achaean navies. Another Illyrian ruler, Longarus, invaded Macedonia and defeated Demetrius II's army shortly before his death in 229 BC. His young son Philip immediately inherited the throne. However, his regent Antigonus III Doson (229–221 BC), nephew of Antigonus II, was proclaimed king after military victories against the Illyrians and Aetolians.

Although the Achaean League had fought Macedonia for decades, Aratus sent an embassy to Antigonus III in 226 BC, seeking an alliance. This was because the Spartan king Cleomenes III was threatening the rest of Greece in the Cleomenean War (229–222 BC). In exchange for military help, Antigonus III demanded that Corinth be returned to Macedonian control, which Aratus agreed to in 225 BC. Antigonus III reformed a Hellenic league, similar to Philip II's League of Corinth. He defeated Sparta at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC. For the first time, Sparta was occupied by a foreign power, restoring Macedonia's leading position in Greece. Antigonus died a year later, leaving a strong kingdom for his successor Philip V.

Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC) was only 17 when he became king. He faced immediate challenges from the Illyrian Dardani and the Aetolian League. Philip V and his allies were successful against the Aetolians in the Social War (220–217 BC). However, Philip V sought peace when he heard about the Dardani's renewed presence in the north and Carthage's victory over the Romans at the Battle of Lake Trasimene in 217 BC. Demetrius of Pharos reportedly convinced Philip V to secure Illyria before invading Italy. In 216 BC, Philip V sent warships into the Adriatic Sea to attack Illyria. Rome noticed this and sent ships to patrol the Illyrian coasts, causing Philip V to retreat and avoid open conflict for a while.

Conflict with Rome

In 215 BC, during the Second Punic War with Carthage, Roman officials stopped a ship carrying a Macedonian envoy and a Carthaginian ambassador to Macedonia. They had a document from Hannibal declaring an alliance with King Philip V. This treaty stated that Carthage had the sole right to negotiate with Rome after its surrender. It also respected Macedonian interests in the Adriatic Sea and promised mutual aid if Rome attacked either Macedonia or Carthage. Although Macedonians were likely only interested in protecting their lands in Illyria, the Romans managed to stop Philip V's plans in the Adriatic during the First Macedonian War (214–205 BC). In 214 BC, Rome sent a naval fleet when Macedonian forces attacked Oricus and Apollonia. When Macedonians captured Lissus in 212 BC and possibly threatened southern Italy to support Hannibal, the Roman Senate encouraged the Aetolian League, Pergamon, Sparta, Elis, and Messenia to fight Philip V. This kept him busy and away from Italy.

A year after the Aetolian League made peace with Philip V in 206 BC, the Roman Republic negotiated the Treaty of Phoenice. This ended the war and allowed Macedonians to keep the settlements they had captured in Illyria. Although Rome rejected an Aetolian request in 202 BC to declare war on Macedonia again, the Roman Senate seriously considered a similar offer from Pergamon and Rhodes in 201 BC. These states grew worried when Philip V allied with Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus invaded the Ptolemaic Empire, while Philip V captured Ptolemaic settlements in the Aegean Sea. Although Rome's envoys convinced Athens to join the anti-Macedonian alliance in 200 BC, the Roman people's assembly rejected the Senate's proposal for war on Macedonia. Meanwhile, Philip V conquered important territories, which led Rhodes to form an alliance against Macedonia. Philip V lost a naval battle in 201 BC and was blockaded.

While Philip V was fighting several Greek naval powers, Rome saw this as a chance to punish a former ally of Hannibal, help its Greek allies, and win a war with limited resources. With Carthage defeated, Rome's strategy changed from protecting Italy to getting revenge on Philip V. However, some historians argue that Rome didn't plan long-term strategies but reacted to crises, getting involved in the Greek world only when allies strongly urged it, despite its own tired people. The Roman Senate demanded that Philip V stop fighting Greek powers and agree to international arbitration. His rejection of their proposal served as propaganda, showing Rome's honorable intentions compared to Macedonia's aggressive response. When the Roman assembly finally approved the declaration of war and gave their ultimatum to Philip V by the summer of 200 BC, he rejected it. This began the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC).

Although the Macedonians defended their territory for about two years, the Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus managed to expel Philip V from Macedonia in 198 BC. Philip and his forces took refuge in Thessaly. When the Achaean League abandoned Philip V to join the Roman-led alliance, the Macedonian king sought peace. But the terms were too strict, so the war continued. In June 197 BC, the Macedonians were defeated at the Battle of Cynoscephalae. Rome, ignoring the Aetolian League's demands to completely destroy the Macedonian monarchy, ratified a treaty. This forced Macedonia to give up most of its Greek possessions, including Corinth, but allowed it to keep its core territory. This was to act as a buffer against Illyrian and Thracian raids into Greece.

Although the Greeks suspected Rome's intentions, Flamininus announced at the Isthmian Games in 196 BC that Rome intended to preserve Greek freedom by leaving no garrisons or demanding tribute. This promise was delayed because the Spartan king Nabis captured Argos, requiring Roman intervention. But the Romans finally left Greece in the spring of 194 BC.

Encouraged by the Aetolian League, the Seleucid king Antiochus III landed with his army in Thessaly in 192 BC and was elected leader by the Aetolians. However, Philip V of Macedon maintained his alliance with the Romans, along with the Achaean League, Rhodes, Pergamon, and Athens. The Romans defeated the Seleucids in 191 BC and 190 BC, forcing them to pay a war fine and give up claims to territories north or west of the Taurus Mountains in 188 BC. In 191–189 BC, Philip V, with Rome's approval, captured some cities in central Greece that had been allied to Antiochus III. Rhodes and Eumenes II of Pergamon gained much larger territories in Asia Minor.

Rome became more involved in Greek affairs and struggled to please everyone. In 184/183 BC, the Roman Senate forced Philip V to give up the cities of Aenus and Maronea, which were declared free cities. This also eased Eumenes II's fears that these Macedonian-held settlements would threaten his lands. Perseus of Macedon (179–168 BC) succeeded Philip V and executed his brother Demetrius, who was favored by the Romans. Perseus then tried to form alliances through marriage and renewed relations with Rhodes, which greatly worried Eumenes II. Although Eumenes II tried to undermine these relationships, Perseus formed an alliance with the Boeotian League and expanded his power into Illyria and Thrace. In 174 BC, he gained control of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi.

Eumenes II went to Rome in 172 BC and spoke to the Senate, accusing Perseus of crimes. This convinced the Roman Senate to declare the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC). Although Perseus's forces won against the Romans in 171 BC, the Macedonian army was defeated at the Battle of Pydna in June 168 BC. Perseus fled but surrendered shortly after. He was brought to Rome and placed under house arrest, where he died in 166 BC.

The Romans officially ended the Macedonian monarchy. They set up four separate allied republics with capitals at Amphipolis, Thessalonica, Pella, and Pelagonia. The Romans imposed strict laws limiting interactions between these republics, including banning marriages between them. However, a man named Andriscus, claiming to be of royal descent, rebelled against the Romans and was declared king of Macedonia. He defeated a Roman army during the Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC). Despite this, Andriscus was defeated in 148 BC at the second Battle of Pydna by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus. His forces occupied the kingdom. This was followed in 146 BC by the Roman destruction of Carthage and victory over the Achaean League. This marked the beginning of Roman Greece and the gradual establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia.

See also

- Ancient Macedonians

- Ancient Macedonian language

- Antigonid Macedonian army

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- Government of Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

- List of ancient Macedonians

- Macedonians (Greeks)

- Macednon

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |