Home Guard (United Kingdom) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Home Guardinitially "Local Defence Volunteers" |

|

|---|---|

Home Guard post at Admiralty Arch in central London, 21 June 1940

|

|

| Active | 14 May 1940 – 3 December 1944 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Role | Defence from invasion |

| Disbanded | 31 December 1945 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Sir Edmund Ironside |

The Home Guard (first called Local Defence Volunteers or LDV) was a group of armed citizen volunteers who helped the British Army during the Second World War. They were active from 1940 to 1944. About 1.5 million local volunteers joined. These were people who couldn't join the regular army. This included those who were too young (under 18) or too old (over 41). It also included people in important jobs that kept the country running. About one in five men who weren't already in the military, police, or civil defence joined.

Their main job was to protect Britain from a possible invasion by Nazi Germany. If the Germans invaded, the Home Guard would try to slow them down. This would give the regular British troops time to get ready. They also guarded important places like factories and communication points. Another key role was to help keep order among civilians during an invasion. This would stop panic and keep roads clear for soldiers. The Home Guard continued to guard coastal areas, airfields, and factories until late 1944. They were officially ended on 31 December 1945, a few months after Germany gave up.

Men aged 17 to 65 could join, but these age rules were not always strict. Some platoons even had a 14-year-old and men in their eighties. Volunteers were not paid, but it was a way for older or less experienced people to help with the war effort.

Contents

- Why the Home Guard was Needed

- How the Home Guard Was Organized and Fought

- Equipment and Training

- Dealing with Spies and Paratroopers

- Uniforms

- Ranks

- American Help

- End of the Home Guard

- Social Impact

- Home Guard in Popular Culture

- Home Guard Honours

- Later Versions of the Home Guard

- Famous Home Guards

- See also

Why the Home Guard was Needed

When Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, people started worrying about a German invasion. Some reports suggested a German attack by sea was coming soon. Many government officials and army leaders didn't believe the threat was real. However, Winston Churchill, who was in charge of the navy at the time, thought it was a serious danger.

Churchill believed that a home defence force should be created. This force would be made up of people who couldn't join the regular army but still wanted to serve their country. In October 1939, Churchill suggested forming a Home Guard of 500,000 men over 40 years old.

Early Volunteer Groups

Even before the government officially acted, some groups of volunteers started forming on their own. For example, in Essex, men who couldn't be called up for the army joined a group called the "Legion of Frontiersmen." Government officials heard about these groups. Some thought the government should encourage them. However, fears of invasion soon faded in 1939, and these early volunteer groups often broke up.

Things changed quickly in May 1940 when Germany invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. German forces reached the English Channel, making a German invasion of Britain seem very likely. People became very worried. There were also fears of a "fifth column" – secret groups in Britain who might help German paratroopers.

Government Under Pressure

The government faced growing pressure to let people arm themselves to defend against an invasion. Newspapers and individuals called for a home defence force. Some suggested that rifle clubs could form the basis of such a force. Others, like Labour MP Josiah Wedgwood, wanted all adults to be trained and given weapons.

Government and military officials were worried about private defence groups forming that the army couldn't control. They thought it would be better to have an official force. This would allow more control and better security for important places like factories and airfields. After quick planning, an improvised plan for a home defence force was ready by 13 May 1940. It was called the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV).

On the evening of 14 May 1940, Anthony Eden, the Secretary of State for War, announced the formation of the LDV on the radio. He called for volunteers, saying: "You will not be paid, but you will receive a uniform and will be armed."

Joining the LDV

Eden asked men aged 17 to 65 who were not in military service to sign up at their local police station. They expected about 500,000 men to volunteer. However, the response was huge! About 250,000 volunteers signed up in the first week. By July, this number had grown to 1.5 million. Many groups, like cricket clubs, formed their own units. Most units were based at workplaces, as employers needed to allow time for training and patrols. Many employers saw the LDV as a way to protect their factories from attack.

Women and the Home Guard

At first, women were not allowed to join the Home Guard. Some women formed their own groups, like the "Amazon Defence Corps." In December 1941, a more organized but unofficial group called the "Women's Home Defence" (WHD) was formed. WHD members received weapons and basic military training. Later, women were allowed to help the Home Guard in support roles. These roles included office work or driving, but not fighting.

Getting Equipment and Support

The War Office worked on setting up the LDV. Eden's announcement made it seem like everyone would get a personal firearm. It would have been better to limit recruitment to the number of weapons available. But once so many volunteers joined, it was impossible to turn them away. However, the regular army still needed weapons first.

The LDV units were organized into military areas, with officers coordinating with local officials. On 17 May, the LDV became official when the government issued an order. Volunteers were divided into sections, platoons, and companies. They were not paid, and their leaders did not have the same power as regular army officers.

Setting up the LDV was difficult. The War Office was also busy with the Dunkirk evacuation, which was happening at the same time. This lack of focus made many LDV members impatient. They were told they would only get armbands with "L.D.V." on them until proper uniforms were made. There was no mention of weapons. This led many units to start their own patrols without official permission. Often, these patrols were led by men who had served in the military before.

Many veterans believed they didn't need training before getting weapons. This led to many complaints. Giving weapons to the LDV was a big problem for the War Office. The regular army needed to be rearmed first. Civilians had been asked to hand in their firearms to police stations. Now, volunteers were allowed to get them back for their LDV duties. In the countryside, people with shotguns formed groups called "parashots" to watch for German paratroopers.

The government said there were many Lee-Enfield rifles left from the First World War. But in reality, there were only 300,000, and they were already planned for the army. Instead, the War Office taught people how to make Molotov cocktails. They also ordered Ross rifles from Canada. Without proper weapons, local units made their own, like grenades and mortars. This spirit of making do with what they had became a key part of the Home Guard.

What Was Their Job?

Another challenge was figuring out the Home Guard's exact role. At first, the army saw the LDV as an "armed police force." Their job was to man roadblocks, watch German troop movements, report information, and guard important places. The War Office thought this passive role was best because the LDV lacked training and equipment.

However, LDV members wanted a more active role. They wanted to hunt down and kill paratroopers and spies, and attack German forces. This difference in ideas caused morale problems. Many members complained that the government was leaving them defenceless. In August, the government changed the LDV's role to include delaying and stopping German forces in any way possible.

Around this time, Churchill, who was now Prime Minister, got involved. He thought the name "LDV" was boring. He suggested renaming it the "Home Guard." Despite some resistance, the LDV was officially renamed the Home Guard on 22 July. Churchill made it clear that volunteers should actively fight German forces, even if it meant breaking old "rules of war." He believed that fighting to the end was better than giving in to the Nazis.

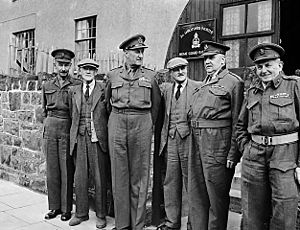

How the Home Guard Was Organized and Fought

By the end of 1940, the Home Guard had 1,200 battalions, 5,000 companies, and 25,000 platoons. Each section was trained to act as a small, independent "battle platoon." They usually had 25 to 30 men on duty at any time. Since volunteers also had full-time jobs, each section had about twice that number of members.

If an invasion happened, Home Guard platoons in a town would be controlled by an army commander. They would use a "runner" (often someone with a motorbike) to send messages. Home Guard units were not given radios until 1942. Each platoon would defend a specific local area and report on enemy activity. They were not expected to join up with the regular army.

Each Home Guard unit would set up a strongpoint, like a fortified building. They would try to defend this strongpoint for as long as possible. They might retreat to another strongpoint but would not surrender as long as they had ammunition. Larger towns would have several Home Guard units, each defending its own strongpoint. These strongpoints were placed to help each other and control roads.

Each battle platoon had a headquarters section with a commander, second-in-command, runner, and at least one sniper. The fighting part of the platoon had three squads of about 8 men. Each squad had an automatic weapons group (with a BAR or Lewis gun) and a rifle/bomb group with rifles, grenades, and sticky-bombs. They would also have a Thompson or Sten sub-machine gun if possible. Men without rifles would use shotguns.

The main idea was "aggressive defence." They would wait until the enemy was close, then attack with bombs, grenades, shotguns, and automatic weapons. They would try to attack from above or from behind to force the enemy to take cover. If the enemy retreated, they would counterattack. The goal was to kill as many Germans as possible.

Their fighting methods were inspired by the Spanish Civil War. They focused on fighting in city areas at close range. Stone buildings would provide cover, and communication between units would be easy. Their shotguns, bombs, and grenades would be most effective in narrow streets, where German tanks would be limited.

Secret Roles of the Home Guard

The Home Guard also had some secret roles. This included sabotage units that would disable factories and petrol stations if an invasion happened. Members with outdoor survival skills, like gamekeepers or poachers, could join the Auxiliary Units. This was a very secret force of highly trained guerrilla fighters. Their job was to hide behind enemy lines after an invasion. They would then attack supply dumps, disable tanks, assassinate collaborators, and kill German officers. They operated from secret underground bases hidden in woods or caves.

These hidden bases, over 600 of them, could support units of different sizes. If an invasion happened, the Auxiliary Units would disappear into their bases. They would not contact local Home Guard commanders, who wouldn't even know they existed. So, even though Auxiliaries were Home Guard volunteers and wore their uniforms, they wouldn't fight in the first defence of their town. They would activate later to cause as much trouble as possible.

Actual Fighting

It's a common mistake to think the Home Guard never fought during the war. In fact, individual Home Guardsmen helped operate anti-aircraft guns as early as the Battle of Britain in 1940. By 1943, the Home Guard ran its own anti-aircraft guns and rockets. They also operated coastal defence artillery and shot at German planes with machine guns. They are credited with shooting down many Luftwaffe aircraft and V-1 flying bombs in 1944. The Home Guard's first official kill was a plane shot down in Tyneside in 1943. The Home Guard in Northern Ireland also fought in gun battles with the Irish Republican Army.

After the German bombing campaign, the Blitz, in 1940 and 1941, many unexploded bombs were left in cities. Home Guard units took on the dangerous job of finding these bombs. If a bomb was found, they would help seal off the area and evacuate civilians. Most Home Guard deaths during the war happened while doing this task. Besides accidents, 1,206 Home Guard members died on duty from unexploded bombs, air attacks, and rocket attacks.

Equipment and Training

For the first few weeks, the LDV had very few weapons. The regular army had priority for all equipment. The government couldn't admit how few weapons the regular troops had. This made the public frustrated that the LDV wasn't getting rifles. Rifles were a big problem because production of new Lee-Enfield rifles had stopped after the First World War. In 1940, there were only about 1.5 million usable military rifles in total. New factories were being built for an updated rifle, but they were not ready yet.

The LDV's original job was to observe and report enemy movements. But this quickly changed to a more active fighting role. Despite this, they had very little training and only basic weapons. These included homemade bombs, shotguns (with special solid ammunition), personal handguns, and even old museum firearms. Patrols were done on foot, by bicycle, or even on horseback. Often, volunteers didn't have uniforms, only an armband with "LDV" on it. Some even used private boats for river patrols.

Many officers from the First World War used their old Webley revolvers. There were also many attempts to make armored vehicles by adding steel plates to cars or trucks. These improvised vehicles included the Armadillo armoured truck and the Bison mobile pillbox.

Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Aircraft Production, helped create the "Car Armoured Light Standard," known as the Beaverette. This was a commercial car with simple armor and a light machine gun. He made sure many of these went to Home Guard units guarding important aircraft factories. LDV units even broke into museums to find weapons. Many veterans had kept German handguns as trophies, but ammunition was hard to find. People also lent their hunting rifles to the LDV. But all these efforts only provided about 8,000 rifles.

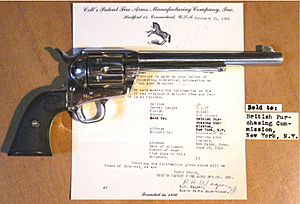

Weapon supplies for the Home Guard greatly improved after July 1940. US President Franklin Roosevelt helped the British government buy 500,000 M1917 Enfield Rifles and 25,000 M1918 Browning Automatic Rifles from US army reserves. The M1917 Enfield rifles were more modern than the Lee-Enfield rifles used by the regular British forces. They hit harder and were more accurate, but they were also heavier. The Browning Automatic Rifles, when used as semi-automatic rifles, gave a lot of extra firepower. Also, the British government bought many Thompson submachine guns, which were first given to the Home Guard starting in 1941.

The British army had lost almost all its Bren Guns at Dunkirk. So, the regular army first used older American Lewis guns. By the end of 1940, about 14,000 American Lewis guns were given to the Home Guard. The Home Guard also received about 4,000 American M1917 Browning machine guns. These American guns used different ammunition than British guns. A red band was painted on the American rifles as a warning.

Within a few months, the Home Guard started getting proper uniforms and equipment. Priority was given to units on the South Coast and those defending key factories. If an invasion had happened in September or October 1940, these Home Guard units would have been well-equipped for defence. After September 1940, the army took over Home Guard training.

However, Home Guard members were still not happy with their weapons until 1943. Not all 1.5 million members could get their own rifle or pistol. The American guns had to be cleaned of thick grease by the Home Guard units themselves. Each gun came with enough ammunition, but Home Guard units were often not allowed to fire them in practice. This was because there were no extra ammunition stocks until America joined the war.

From 1942, Thompson guns were taken from the Home Guard and given to Commando forces. But they were replaced by many Sten submachine guns. For the first time, all Home Guard members could have their own firearm.

Home Guard training taught them to use improvised grenades and bombs in city fighting against tanks. Two main weapons were recommended: the satchel bomb (an explosive in a canvas bag) and the Molotov cocktail (a bottle with petrol and a gelling agent).

The Home Guard also received weapons the regular army didn't want anymore, like the Blacker Bombard anti-tank weapon and the Sticky bomb. They also used weapons that were cheap to make, like the Northover Projector (a mortar), the No. 76 Special Incendiary Grenade (a glass bottle with flammable material), and the Smith Gun (a small artillery gun that could be towed by a car).

"Croft's Pikes"

By late 1940, the Home Guard had many rifles and machine guns, but 739,000 men were still unarmed. In June 1941, Churchill said that "every man must have a weapon of some sort, be it only a mace or a pike." Government workers took him seriously and ordered 250,000 pikes. These were long steel tubes with old bayonets welded to the end. When the first pikes arrived, there was an uproar, and it's thought none were actually used.

Captain Godfrey Nicholson, an MP, said in Parliament that the pikes were "an insult" if not a joke. Lord Croft, a government official, defended the decision, saying the pike was "a most effective and silent weapon." His name became linked to the pikes. The weapon shortage was finally solved when the first mass-produced Sten submachine guns became available in early 1942.

Dealing with Spies and Paratroopers

The German invasion of Poland in 1939 used special units that looked like civilians or wore enemy uniforms. In 1940, German paratroopers landed in the Netherlands and took over key points. British people thought these quick German victories were due to German paratroopers working with a "fifth column" – secret Nazi supporters – in each country.

The British press suggested that the German Gestapo had lists of British civilians. "The Black Book" was for anti-Nazis and Jews to be rounded up. "The Red Book" was for Nazi sympathizers who would help the invaders. The police received many reports about suspected spies. General Edmund Ironside, head of Home Forces, even believed that rich landowners had prepared secret landing strips for German paratroopers.

The government's fears seemed confirmed in May 1940 when Tyler Kent, an American spy for Germany, was caught. He had a list of 235 names from a pre-war anti-war group. This was not made public, but people wanted the names of suspected spies given to local Home Guard units. Many British fascists, including Oswald Mosley, were arrested.

However, the government soon realized there was no real organized "fifth column" in Britain. Churchill later said he always thought the threat was exaggerated. From then on, the main way to deal with fears of spies was to put suspicious names on an "Invasion List." The Home Guard was expected to counter any spy activity.

Even though there was no active German spy network in Britain, Home Guard volunteers still believed a big part of their job was to catch potential spies. They also thought they would hunt down and kill any spies who helped an invasion and stop them from meeting German paratroopers.

Defence Against Paratroopers

The use of German paratroopers in Rotterdam, where they landed in a football stadium and then used private transport to reach the city centre, showed that no place was safe. It was widely reported that paratroopers in the Netherlands were helped by German servants. From July 1940, the Home Guard set up observation posts. Soldiers watched the skies every night. They were first armed with shotguns, then with M1917 rifles.

British intelligence reports in 1940 suggested that German paratroopers often used "dirty tricks." They might wear enemy uniforms or pretend to be civilians. It was claimed that lone paratroopers would fake surrender to kill their captors. Early Home Guard training manuals warned about this, advising that "pretenders should be promptly and suitably dealt with."

After the German capture of Crete in May 1941, the Home Guard learned more about paratrooper tactics. They realized that paratroopers were very vulnerable for a while after landing, as they only had a pistol and knife until they found their equipment containers. This role of quickly responding to paratrooper drops was perfect for local Home Guard units. So, defence against paratroopers was a major focus of Home Guard training. Even after the immediate invasion threat passed, Home Guard units guarding important factories received extra equipment, like Beaverette armored cars, specifically for paratrooper raids.

To spread the word during an invasion, the Home Guard created a simple code. For example, the word "Cromwell" meant a paratrooper invasion was about to happen. "Oliver" meant the invasion had started. The Home Guard also planned to use church bells as a call to arms. This led to strict rules about who had keys to bell towers, and church bells were forbidden at all other times.

Uniforms

On 22 May 1940, eight days after the LDV was formed, the War Office announced that 250,000 field service caps would be the first part of the new uniform. They also said that khaki armbands with "LDV" in black were being made. In the meantime, LDV units made their own armbands from whatever materials they could find. Local Women's Voluntary Service groups often helped make them, sometimes using old leg wraps donated by veterans.

The British Army used loose-fitting work clothes called "Denim Overalls." These were made of khaki cotton fabric and included a short jacket and trousers. They were designed to be worn over the 1938 pattern Battle Dress. It was announced that 90,000 sets of denim overalls would be given out immediately, with more to follow.

On 25 June, Anthony Eden announced that the LDV uniform would include "one suit of overalls... a field service cap, and an armlet bearing the letters 'L.D.V.'" On 30 July 1940, Eden also announced that the Home Guard (as the LDV was renamed) would receive military boots when available.

Getting uniforms was slow because of shortages. The army also needed to be re-equipped after the Fall of France. In August, Eden announced that there wasn't enough material for denim overalls. So, regular battle dress uniforms would be given to the Home Guard instead. By the end of 1940, the government had approved spending £1 million to provide battle dress to the entire force. They also announced that blankets and greatcoats would be issued.

As winter came, many Home Guardsmen complained about patrolling without warm overcoats. So, a large cape made of heavy fabric was quickly designed and given out. There weren't enough 1937 Pattern Web Equipment sets (which included a belt, ammunition pouches, and a haversack) for the Home Guard. So, a simpler set made of leather and canvas was produced. The awkward leather "anklets" were especially unpopular. They were worn instead of the webbing gaiters used by the army. The lack of steel helmets was also a big concern, especially for those on guard duty during the Blitz, when there was a high risk of being hit by bomb fragments. This problem was slowly fixed over time.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, the LDV was controlled by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. They were known as the Ulster Defence Volunteers, and later the Ulster Home Guard. The police had large amounts of black cloth. This cloth was quickly made into uniforms similar to the denim overalls by local clothing factories. The Ulster Home Guard wore their black uniforms until Battle Dress uniforms were issued in April 1941.

Ranks

When the Home Guard first started, it had its own rank system. Since it was a volunteer group, officers were appointed and did not hold a King's Commission (a formal military appointment).

In November 1940, it was decided to make the Home Guard ranks similar to the regular army. From February 1941, officers and men used regular army ranks. The rank of "Volunteer" was changed to "Private" in the spring of 1942.

After November 1940, officers were given a King's Commission. However, they were considered lower in rank than a regular army officer of the same rank, but higher than regular army officers of a lower rank.

| Home Guard Pre-November 1940 | Zone Commander | Group Commander | Battalion Commander | Company Commander | Platoon Commander | No equivalent | Squad Commander | Volunteer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home Guard Post-November 1940 | Brigadier | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant | Warrant Officer Class I | Warrant Officer Class II | No equivalent | Sergeant | Corporal | Lance Corporal | Volunteer |

| Rank insignia Post-November 1940 |  |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Regular Army Equivalents | Brigadier | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant | Warrant Officer Class I | Warrant Officer Class II | Colour Sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Lance Corporal | Private |

American Help

Churchill saw the Home Guard as a great way to encourage pro-British feelings in the United States. He hoped that if Americans were interested in the Home Guard, it might help bring the US into the war against Germany. Giving many modern American rifles and machine guns to the Home Guard was also good for British propaganda. This propaganda showed that "Britain can take it" and would never give in to the Nazis. It also showed Britain as a place of traditional values. This led to films like Mrs. Miniver showing the Home Guard defending ideal rural English villages. However, most Home Guard units were actually in towns and cities, and most volunteers were factory workers.

Committee for American Aid

In November 1940, a committee was formed to collect donations of weapons and binoculars from American civilians. These were given to Home Guard units. Police revolvers from US city police departments were especially useful. Many of these went to help the secret Home Guard Auxiliary units.

1st American Squadron of the Home Guard

On 17 May 1940, the United States Embassy told the 4,000 Americans living in Britain to go home. A stronger message in June warned that it might be their last chance to leave until after the war. Many Americans chose to stay. On 1 June 1940, the 1st American Squadron of the Home Guard was formed in London. They usually had 60–70 members and were led by General Wade H. Hayes.

The US ambassador in London, Joseph Kennedy, was against Americans from a neutral country joining. He worried that if there was an invasion, these American civilians might be shot by the Germans.

End of the Home Guard

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 made it clear that an immediate invasion of Britain was no longer expected. But at first, the British military thought the Soviets might not last long. So, the Home Guard had to stay ready in case the German threat returned. The Home Guard continued to guard posts and perform other duties. This freed up regular troops for fighting overseas. They also took over operating coastal artillery and anti-aircraft batteries. In 1942, a law allowed for compulsory enrollment in the Home Guard for men aged 42 to 51 if units were low on members.

Disbandment

Only when the war on the Eastern Front clearly turned against Germany in 1943 did the need for the Home Guard lessen. Even then, military planners and the public still worried that the Germans might launch raids on Southern England. These raids could disrupt preparations for the Second Front (the Allied invasion of Europe) or try to assassinate Allied leaders. After the successful Allied landings in France, the Home Guard was formally stood down on 3 December 1944. They were finally disbanded on 31 December 1945.

Recognition

Male members received a certificate that thanked them for their service. If they had served more than three years and asked for it, they would also get the Defence Medal. It wasn't until 1945 that women who had helped as auxiliaries received their own certificate.

Social Impact

Anthony Eden said in November 1940 that the Home Guard "was a miracle of improvisation." He believed it showed the special spirit of the British people. General Sir John Burnett-Stuart said the Home Guard "was the outward and visible sign of the spirit of resistance."

Home Guard in Popular Culture

The Home Guard has appeared in many books, films, and TV shows.

- Alison Uttley included the Home Guard in her Little Grey Rabbit children's stories with Hare Joins The Home Guard in 1942.

- The wartime Hollywood film Mrs. Miniver shows a father joining the Local Defence Volunteers and helping with the Dunkirk evacuation.

- The British wartime film Went the Day Well? (1942) shows how a village's Home Guard and people defeat German paratroopers and local spies.

- Noël Coward wrote a song in 1943, "Could You Please Oblige Us with a Bren Gun?" This song made fun of the disorganization and lack of supplies in the Home Guard.

- The Home Guard also played a big part in the 1943 film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. The main character, an old soldier, joins the Home Guard and becomes a leader. The film celebrates the Home Guard's idea that old "rules of war" were no longer important against Nazism.

- The 1943 British film Get Cracking stars George Formby as a Home Guard lance corporal. His platoon is rivals with other local Home Guard sections.

- The Home Guard was also featured in the 1971 Disney film Bedknobs and Broomsticks.

- The film Hope and Glory (1987) shows a Home Guard unit shooting down a runaway barrage balloon.

- The British detective series Foyle's War (2003) has an episode called "War Games" set in World War II Hastings, featuring the Home Guard.

- An episode of the Doctor Who spin-off The Sarah Jane Adventures in 2010 featured the Home Guard.

Dad's Army

The Home Guard became famous through the British television comedy Dad's Army. This show followed a platoon in the fictional town of Walmington-on-Sea. It is widely seen as keeping the Home Guard's efforts in public memory. The show was written by Jimmy Perry and David Croft. It was loosely based on Perry's own experiences in the Home Guard.

Dad's Army was broadcast on BBC Television from 1968 to 1977. It had 9 series and 80 episodes. There was also a radio version, two films, and a stage show. The series often had 18 million viewers and is still shown worldwide.

Dad's Army mainly focused on Home Guard volunteers who couldn't join the regular army because of their age. So, the show featured older British actors like Arthur Lowe, John Le Mesurier, Arnold Ridley, and John Laurie. (Ridley and Laurie had actually served in the Home Guard during the war).

In 2004, Dad's Army was voted the fourth best British sitcom in a BBC poll. It has influenced British popular culture, with its catchphrases and characters being well known. It also highlighted a forgotten part of defence during the Second World War. A film featuring Bill Nighy, Sir Michael Gambon, Toby Jones, and Sir Tom Courtenay was released in 2016.

Home Guard Honours

| Awarded to the Home Guard |

Ribbon | Medal | Notes |

| 2 (Section Commander George Inwood), (Lieutenant William Foster) | George Cross (GC) | Both Posthumous (awarded after death) | |

| 24 | Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) | Military Division | |

| 129 | Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) | Military Division | |

| 396 | Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) | Military Division | |

| 13 | George Medal (GM) | ||

| 408 | British Empire Medal (BEM) | Military Division | |

| 1 | British Empire Medal (BEM) | Civil Division | |

| 1 | Military Medal (MM) | ||

| ? | Defence Medal (United Kingdom) | ||

| 1 | Mentioned in dispatches | ||

| 58 | King's Commendation for Brave Conduct | 2 were Posthumous |

Later Versions of the Home Guard

Home Guard: 1952–1957

After the original Home Guard was disbanded, people suggested bringing it back because of a new threat from the Soviet Union. Planning started in 1948. The idea was for the Home Guard to guard important places and help against invasion.

Nothing concrete happened until Winston Churchill became Prime Minister again in 1951. Churchill believed there could be an attack on Britain by Soviet paratroopers.

A law was passed in December 1951 to bring back the Home Guard. Enrollment started on 2 April 1952. The goal was to recruit 170,000 men in the first year. However, by November 1952, only 23,288 had joined.

The new Home Guard wore standard army uniforms and a midnight blue beret. They also received helmets, greatcoats, and webbing. Their weapons included the Lee-Enfield No 4 Mk 1 rifle, the Mk II Sten sub-machine gun, and the Bren gun. They also had older anti-tank weapons and mortars. A group of the Home Guard even marched in the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953.

There was a lot of criticism about the cost of the Home Guard. So, in December 1955, it was announced that the Home Guard would be reorganized. All battalions would be reduced to a small core staff. On 26 June 1957, it was announced that the Home Guard would be disbanded on 31 July, saving £100,000 that year.

Home Service Force: 1982–1993

During the Cold War, the Home Service Force was created in 1982. Recruitment began in 1984, but only those who had served in the armed forces before could join. About 48 units were formed. After the Cold War ended, the force was disbanded in 1992.

Famous Home Guards

- Tony Benn, a Labour politician (Bromyard and Oxted Home Guard)

- Zulfiqar Ali Bukhari, a famous broadcaster (BBC Home Guard)

- Cecil Day-Lewis, a poet and later Poet Laureate (Musbury Home Guard)

- George Formby, actor, singer, and comedian (Blackpool Home Guard)

- John Laurie, actor, known for Dad's Army (Paddington Home Guard)

- C S Lewis, writer (Oxford Home Guard)

- Patrick Moore, astronomer and broadcaster (East Grinstead Home Guard)

- George Orwell, author and journalist (Sergeant, Greenwich Home Guard)

- Jimmy Perry, scriptwriter for Dad's Army (Barnes and Watford Home Guard)

- Arnold Ridley, actor, known for Dad's Army (Caterham Home Guard)

See also

In Spanish: Home Guard para niños

In Spanish: Home Guard para niños

- Operation Sea Lion, Germany's plan to invade Britain

- Auxiliary Units, a secret British force of 1940

- Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

- Volunteer Training Corps (World War I), the British home defence force of World War I

International:

- Volkssturm, German national militia in World War II

- Volunteer Defence Corps, Australian Home Guard

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |