Sticky bomb facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sticky bomb |

|

|---|---|

Sticky bombs being manufactured

|

|

| Type | Anti-tank hand grenade |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| Used by | United Kingdom Canada Australia France |

| Wars | Second World War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Stuart Macrae |

| Designed | 1940 |

| Manufacturer | Kay Brothers Company |

| Produced | 1940-1943 |

| No. built | 2.5 million |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2.25 lb (1.02 kg) |

| Length | 9 in (230 mm) |

| Diameter | 4 in (100 mm) |

|

|

|

| Filling | Nitroglycerine (Nobel's No. 823 explosive) |

| Filling weight | 1.25 lb (0.57 kg) |

|

Detonation

mechanism |

Timed, 5 seconds |

The "Grenade, Hand, Anti-Tank No. 74", often called the S.T. grenade or simply sticky bomb, was a special hand grenade made in Britain during World War II. It was one of many quick-fix anti-tank weapons created for the British Army and Home Guard. These weapons were needed after Britain lost many of its anti-tank guns in France, following the evacuation from Dunkirk.

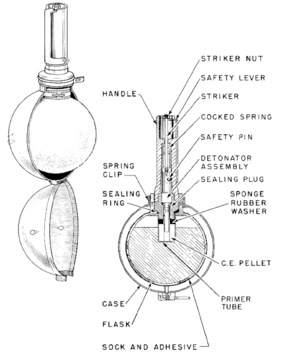

The sticky bomb was designed by a team including Major Millis Jefferis and Stuart Macrae. It had a glass ball filled with an explosive called nitroglycerin. To use it, a soldier would pull a pin, which made the outer casing fall off, showing the sticky ball. Pulling another pin armed the bomb. The soldier would then try to stick it onto an enemy tank. When the handle was let go, a lever started a five-second timer, and then the bomb exploded.

The sticky bomb had some problems. The army's weapons board didn't approve it at first. However, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, insisted it be made. About 2.5 million sticky bombs were produced between 1940 and 1943. They were mostly given to the Home Guard, but British and Commonwealth soldiers also used them in North Africa and by Allied forces in Italy and New Guinea. The French Resistance also received some.

Contents

How the Sticky Bomb Was Developed

In 1938, Major Millis Jefferis thought of a new anti-tank weapon. He wanted an explosive that would flatten out when it hit a tank. This way, the explosion's power would focus on a small spot and break through the tank's armor. This type of explosive is sometimes called a "squash head" charge.

Jefferis worked with scientists from Cambridge University. They experimented with bicycle inner tubes filled with plasticine to act like the explosive. These were made sticky and had wooden handles. Early tests showed it was hard to aim them, and they only stuck to metal bins, not real tanks.

Why Britain Needed New Weapons

After the Battle of France and the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940, Britain feared a German invasion. The British Army didn't have enough weapons to defend the country. Many anti-tank guns were left behind in France. Only 167 were left in Britain, and there was very little ammunition.

Because of this, Jefferis realized his sticky bomb idea could be very useful. He led a department called MIR(c), which usually developed weapons for resistance groups in Europe. Now, {{nowrap|MIR(c)]] was tasked with creating the sticky bomb for Britain's defense. Robert Stuart Macrae was put in charge of designing it.

Designing the Sticky Part

A printer named Gordon Norwood suggested using a fragile container for the explosive gel. He showed how a light bulb inside a wool sock could work. When thrown, the glass would break, and the bomb would flatten out. Tests with glass flasks filled with cold porridge showed this was a good idea.

The bomb needed a delay fuse so the thrower could get away safely. The wool sock was covered in a sticky substance to make sure the bomb stayed on the target. A special non-sticky handle was added. Inside the handle, a lever started a five-second timer when released, just like other hand grenades.

Macrae found a company called Kay Brothers Ltd. in Stockport that made a sticky substance called birdlime. Their chief chemist quickly developed a suitable adhesive for the bomb.

The Explosive and Early Problems

The explosive inside the bomb was developed by ICI. It was based on nitroglycerin but had special ingredients to make it safer and thicker, like Vaseline. The glass flask held about 1.25 pounds (0.57 kg) of this explosive. A light metal casing protected the sticky surface and was removed by pulling a safety pin.

Early sticky bombs had problems. They sometimes leaked or broke during transport. The explosive, pure nitroglycerin, is usually very sensitive. However, the ICI mixture proved to be very safe.

The army's Ordnance Board still didn't approve the bomb for regular use. But Prime Minister Winston Churchill was worried about Britain's defenses. He learned about the sticky bomb and pushed for it to be developed. In October 1940, he famously ordered: "Sticky bomb. Make one million."

Tests showed the bomb didn't stick well to wet or muddy tanks. Churchill was not happy about this. He told his generals to keep working on it and warned them not to be lazy.

Despite the problems, the sticky bomb was important because Britain had few other weapons to fight tanks. It could punch through tank armor, which other simple weapons like Molotov cocktails couldn't do.

Churchill believed soldiers and even civilians would bravely run up to tanks and stick the bomb on them, even if it cost their lives. He planned to use the slogan "You can always take one with you."

After many delays and improvements, including changing the glass flask to plastic, the sticky bomb (now called the No. 74 grenade Mk II) was finally approved. Production increased, and it became a standard weapon. Between 1940 and 1943, about 2.5 million were made.

How the Sticky Bomb Was Designed

The sticky bomb had a glass ball filled with 1.25 pounds (0.57 kg) of a thick nitroglycerin explosive. This ball was covered in a fabric called stockinette and then coated with a very sticky substance. A thin metal casing, made of two halves, went around the ball and was held by a wooden handle. Inside the handle was a five-second fuse.

The handle also had two pins and a lever. To use it, a soldier would pull out the pins. This made the metal casing fall away and armed the bomb. The soldier would then run up to a tank and stick the grenade firmly onto its side. The goal was to break the glass ball and spread the sticky explosive onto the tank. When the lever was released, the fuse would start, and the bomb would explode after five seconds.

Design Challenges

The sticky bomb had several design problems. Soldiers were told to place the bomb by hand, not throw it. This meant the sticky part could easily get stuck to their uniform. If this happened, they would have to try to pull it off while still holding the lever, which was very dangerous.

Also, over time, the nitroglycerin inside could become unstable, making the bomb even harder and more dangerous to use. Since it was a short-range weapon, soldiers were trained to hide until a tank passed them. Then, they would stick the bomb to the rear of the tank, where the armor was thinnest. Soldiers were relatively safe a few yards away, as long as they were not in the path of the handle when it exploded. The improved Mark II version used a plastic casing instead of glass and a different detonator.

How the Sticky Bomb Was Used in War

A training guide from August 1940 said the sticky bomb was a portable explosive device that could be "quickly and easily applied." It was believed to work against armor up to one inch (25 mm) thick. It was good for small tanks, armored cars, and weak spots on larger tanks.

Soldiers could drop it from an upstairs window or place it by hand with enough force to break the glass and spread the explosive. It could also be placed first and then pulled away using a string. The Australian Army is credited with developing the technique of placing the bomb directly onto a tank instead of throwing it. This was safer because the explosion would shoot the handle away like a bullet, keeping the soldier safe if they were not in its path. Placing the bomb by hand also made it stick better and penetrate thicker armor.

By July 1941, 215,000 sticky bombs had been made. Almost 90,000 were sent overseas to North Africa, South Africa, the Middle East, and Greece, where they were useful. The rest were stored or given to army and Home Guard units.

The sticky bomb was first given to Home Guard units in 1940. Even with its flaws, they seemed to like it. Although the army's board didn't approve it for regular units, some were used for training. However, many sticky bombs did make their way to British and Commonwealth soldiers fighting in the North African campaign. In February 1943, during a German advance, sticky bombs destroyed six German tanks.

Australian Army units also used them during the Battle of Wau and the Battle of Milne Bay. Various Allied units, including the First Special Service Force, used them at the Anzio Beachhead in Italy. A large number were also given to the French Resistance.

Recognition for the Inventors

In 1947, a special commission looked at claims from Macrae and the managing director of Kay Brothers. Macrae said he didn't invent the bomb but developed it as part of his job. In 1951, the commission decided that Macrae should receive £500 (about £17,000 today) and Gordon Norwood received £250 (about £8,500 today) for their contributions.

Who Used the Sticky Bomb

See also

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |