PIAT facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Projector, Infantry, Anti Tank |

|

|---|---|

PIAT at the Museum of Army Flying

|

|

| Type | Anti-tank weapon |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1943–1950 |

| Used by | British Empire & Commonwealth |

| Wars | |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Major Millis Jefferis |

| Designed | 1942 |

| Manufacturer | Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd., various others. |

| Produced | August 1942 |

| No. built | 115,000 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 32 lb (15 kg) |

| Length | 39 in (0.99 m) |

|

|

|

| Calibre | 83 mm (3.3 in) |

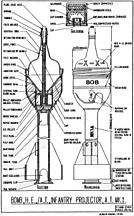

| Action | Spigot mortar |

| Muzzle velocity | 250 ft/s (76 m/s) |

| Effective firing range | 115 yd (105 m) |

| Maximum firing range | 350 yd (320 m) |

| Sights | Aperture sight |

| Filling | Shaped charge |

| Filling weight | 2.5 lb (1.1 kg) |

|

Detonation

mechanism |

Impact |

The Projector, Infantry, Anti Tank (PIAT) Mk I was a special weapon used by soldiers during the Second World War. It was made in Britain to help infantry (foot soldiers) fight against enemy tanks. The PIAT was designed in 1942 and started being used in 1943.

This weapon worked like a spigot mortar. It launched a 2.5-pound (1.1 kg) bomb that used a special type of explosive called a shaped charge. This bomb could hit targets up to 115 yards (105 m) away when aiming directly at a tank. It could also fire bombs up to 350 yards (320 m) for other targets, like buildings.

The PIAT had some good points. It could punch through tank armor much better than older anti-tank rifles. It also didn't have a "back-blast," which is a dangerous burst of gas that comes out the back of some rocket launchers. This meant soldiers could use it without giving away their position or hurting their friends nearby. It was also fairly simple to build.

However, the PIAT also had its downsides. It had a strong kick when fired, and it was hard to get ready to shoot (cocking it). Also, the early bombs sometimes didn't work as they should.

The PIAT was first used in 1943 during the Tunisian campaign. British and other Commonwealth soldiers used it until the early 1950s. Other countries and groups, like the Soviet Union and the French resistance, also got and used PIATs. Six soldiers even won the Victoria Cross, Britain's highest award for bravery, for using the PIAT in battle.

Contents

How the PIAT Was Developed

At the start of the Second World War, British soldiers didn't have very good weapons to fight tanks. They had the Boys anti-tank rifle and the No. 68 AT grenade. But these weapons weren't strong enough. The No. 68 grenade was too small to do much damage. The Boys rifle was heavy and only worked against light tanks from a very short distance. By 1941, it was clear that a new, better weapon was needed.

The Idea of Shaped Charges

The idea behind the PIAT started a long time ago, in 1888. An American engineer named Charles Edward Munroe found that explosives caused more damage if they had a hollow space facing the target. This is called the 'Munroe effect'. Later, a German scientist found that lining this hollow space with metal made it even more powerful.

By the 1930s, a Swiss engineer named Henry Mohaupt improved this idea. He created "shaped charge" ammunition. This kind of bomb had a metal cone inside its explosive warhead. When the bomb hit a target, the explosive turned the cone into a super-fast spike of metal. This spike could punch a small hole in armor and send a shockwave and pieces of metal inside the tank, causing a lot of damage. The No. 68 anti-tank grenade used this technology.

The Spigot Mortar Idea

While shaped charges were being developed, a British officer named Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Blacker was working on a new type of mortar. Instead of firing a shell from a long barrel, he wanted to use a "spigot mortar" system. This system had a steel rod (the spigot) fixed to a base. The bomb itself had the propellant (the stuff that makes it fly) in its tail. When the bomb was pushed onto the spigot, the propellant fired, launching the bomb. This design allowed for larger bombs because the "barrel" was inside the bomb itself.

Blacker first made a light mortar called the 'Arbalest', but it wasn't chosen by the army. He then tried to make a hand-held anti-tank weapon using the spigot idea. He found it hard to make the bomb go fast enough to pierce armor. But he kept working and created the Blacker Bombard. This was a larger spigot system that could launch a 20-pound (9 kg) bomb about 100 yards (90 m). These bombs couldn't pierce armor, but they could still damage tanks. Many Blacker Bombards were given to the Home Guard in 1940 to defend against invasion.

The Birth of the PIAT

When Blacker learned about shaped charge ammunition, he realized it was perfect for a hand-held anti-tank weapon. Shaped charges didn't need to be fired at super high speeds to work. He then designed a shaped charge bomb with propellant in its tail. This bomb fit into a shoulder-fired launcher. The launcher had a metal case with a big spring and a spigot inside. When the trigger was pulled, the spigot hit the bomb's tail, firing it up to 140 metres (150 yd) away. Blacker called this weapon the 'Baby Bombard'.

However, when the Baby Bombard was tested in 1941, it had many problems. The casing was weak, the spigot didn't always fire, and the bombs often didn't explode when they hit the target.

Blacker moved to other projects, and his colleague, Major Millis Jefferis, took over the Baby Bombard. Jefferis took the weapon apart and rebuilt it. He combined it with a shaped charge mortar bomb to create what he called the 'Jefferis Shoulder Gun'. He made some special armor-piercing bombs and tested the weapon. It successfully pierced the target, but a piece of metal flew back and hurt a soldier. Jefferis then fired it himself, and it worked without hurting him.

The army was impressed. They fixed the problems with the ammunition and renamed the Shoulder Gun the Projector, Infantry, Anti Tank (PIAT). Production of the PIAT started in August 1942.

How the PIAT Was Designed

The PIAT was 39 inches (0.99 m) long and weighed 32 pounds (15 kg). It could hit targets directly up to 115 yards (105 m) away and up to 350 yards (320 m) for indirect shots. One soldier could carry and use it, but it was usually used by a two-person team. The second soldier would carry extra bombs and help load.

The main part of the PIAT was a steel tube. Inside were the spigot, the trigger, and a large spring. At the front, there was a small tray where the bomb was placed. The spigot moved forward into this tray. There was a padded rest for the soldier's shoulder and simple sights for aiming. The bombs had hollow tails with a small propellant cartridge inside and a shaped charge warhead.

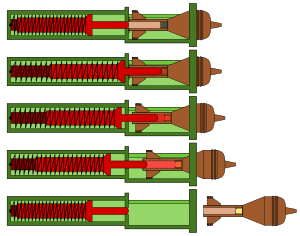

Getting Ready to Fire

Getting the PIAT ready to fire (cocking it) was tricky. The soldier had to stand the PIAT on its butt, step on the shoulder pad, and twist the weapon to unlock it. Then, they had to pull the main body of the weapon upwards. This pulled the big spring back until it locked into place. After that, they would lower the body and twist it back to lock it. This process was hard for smaller soldiers or when lying down.

However, soldiers were taught to cock the PIAT before they expected to use it in battle. So, they usually carried it ready to fire, but unloaded. If it fired correctly, the recoil would automatically cock the weapon for the next shot.

Using the PIAT in Battle

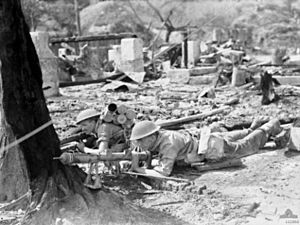

Soldiers were trained to use the PIAT by surprise, hiding from the enemy. They tried to attack enemy tanks from the sides or rear, where the armor was weaker. Because the bomb was powerful and used at close range, soldiers needed good cover, like a trench, to protect themselves from the explosion. The PIAT was also useful for destroying enemy positions in buildings or bunkers. It could even be used like a simple mortar by resting the shoulder pad on the ground.

Despite being heavy and hard to cock, the PIAT had important advantages. Its spigot design allowed it to fire a large, powerful shaped charge bomb. This meant it could penetrate almost any tank armor throughout the war. It was also simple and strong. Unlike the American bazooka, the PIAT had no back-blast. This was a big plus because it meant soldiers could use it safely in tight spaces, like in cities, without giving away their position.

However, it was still very heavy and bulky, which soldiers didn't like carrying. Early bombs also had problems with reliability and accuracy. Even though the PIAT could theoretically punch through about 100 millimetres (4 in) of armor, it was often hard to hit targets accurately. Tests in 1944 showed that even skilled users only hit a target 60% of the time at 100 yards (90 m). Also, about 25% of the bombs didn't explode when they hit.

Ammunition and Its Effects

The PIAT's bombs used the shaped charge principle. If the bomb hit the target correctly, this allowed it to punch through almost all types of enemy armor at close range.

Here are the main types of ammunition used in 1943:

- Service Bomb: This was the main anti-tank bomb. It had the shaped charge warhead.

- Drill Bomb: This was a black bomb, marked "Drill." It was used for practice loading the weapon, but it couldn't be fired.

- Practice Bomb: This was a white, heavy steel cylinder. It was a smaller practice round that could be fired many times with new propellant.

- Inert Bomb: This was a black bomb with a yellow ring, marked "Inert." It was the same size and weight as a live bomb and had a live propellant cartridge, but no explosive warhead. It could be fired once for training.

The bombs came in cases that held three rounds. The propellant was already in the bomb, but the fuses (which make it explode) were kept separate until needed.

Early on, it was hard to make the bomb explode reliably when hitting tanks at an angle. This problem was fixed with improved fuses. The PIAT's manual from 1943 said the bomb had "Excellent penetration" and could go through tank armor and thick concrete. It also noted that it could be used "as a house-breaker," meaning it could destroy buildings.

Operational History

The PIAT was used by British and Commonwealth forces in all the places they fought during World War II.

World War II Use

It started being used in early 1943, first seeing action in March during the Tunisia Campaign. Each British infantry platoon (a small group of soldiers) usually had one PIAT. Larger companies had three PIATs at their headquarters to give out as needed. British Commandos also used PIATs.

In the Australian Army, the PIAT was sometimes called "Projector Infantry Tank Attack" (PITA). Australian soldiers used it against Japanese tanks, vehicles, and bunkers during the Borneo campaign of 1945.

A Canadian Army study in 1944-45 asked 161 officers about different infantry weapons. The PIAT was ranked as the most "outstandingly effective" weapon.

After the Invasion of Normandy, British officers found that PIATs destroyed 7% of all German tanks knocked out by British forces. However, when German tanks started adding "armored skirts" (extra armor that made shaped charges explode too early), the PIAT became less effective.

The Soviet Union received 1,000 PIATs and 100,000 rounds of ammunition from Britain. Resistance groups in Occupied Europe also used the PIAT. During the Warsaw Uprising, Polish fighters used it against German forces. The French resistance used it when they didn't have mortars or artillery.

Six soldiers won the Victoria Cross for their brave actions using the PIAT:

- In Italy, on May 16, 1944, Fusilier Frank Jefferson used a PIAT to destroy a German tank and stop an enemy attack.

- On June 6, 1944, Company Sergeant Major Stanley Hollis used a PIAT to attack a German field gun.

- On June 12, 1944, Rifleman Ganju Lama used a PIAT to destroy two Japanese tanks attacking his unit in Manipur. He got very close to the tanks, within thirty yards (27 m), because he wasn't sure he could hit them from farther away.

- During the Battle of Arnhem (September 19-25, 1944), Major Robert Henry Cain used a PIAT to disable an enemy assault gun and force three other tanks to retreat.

- On the night of October 21/22, 1944, Private Ernest Alvia ("Smokey") Smith used a PIAT to destroy a German tank. He then fought off about 30 enemy soldiers.

- On December 9, 1944, Captain John Henry Cound Brunt used a PIAT and other weapons to help stop a German attack in Italy.

After World War II

The PIAT was used until the early 1950s. It was then replaced by newer weapons like the ENERGA anti-tank rifle grenade and the American M20 "Super Bazooka". The Australian Army used PIATs briefly at the start of the Korean War before switching to the M20 "Super Bazooka."

The Haganah and the new Israel Defence Force (IDF) used PIATs against Arab tanks during the 1947–1949 Palestine war. French and Việt Minh forces also used PIATs during the First Indochina War.

Users

Australia

Australia Belgium

Belgium Canada

Canada Free French Forces

Free French Forces Kingdom of Greece

Kingdom of Greece India

India Israel

Israel Italy (Co-Belligerent Army and partisans)

Italy (Co-Belligerent Army and partisans) Luxembourg

Luxembourg The Netherlands (known as granaatwerper tp (tegen pantser))

The Netherlands (known as granaatwerper tp (tegen pantser)) New Zealand

New Zealand Polish Underground

Polish Underground Soviet Union

Soviet Union United Kingdom

United Kingdom Yugoslavia Used by Yugoslav partisans

Yugoslavia Used by Yugoslav partisans Malaysia

Malaysia Philippines

Philippines North Vietnam

North Vietnam

Combat Use

World War II:

- Battle of Normandy (France 1944)

- Battle of Arnhem (Netherlands, 1944)

- Battle of Ortona (Italy, 1943)

- Battle of Villers-Bocage (Normandy, France, 1944)

- Operation Epsom (Normandy, France, 1944)

- Operation Perch (Normandy, France, 1944)

- Warsaw Uprising (1944)

- Battle of Yad Mordechai (Israel, 1948)

- Battles of the Kinarot Valley (Israel, 1948)

- Battle of Longewala (India, 1971)

See also

- Panzerfaust

- Bazooka

- RPG-1

- Type 4 70 mm AT Rocket Launcher

- Blacker Bombard

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |