Benedictines facts for kids

|

Latin: Ordo Sancti Benedicti

|

|

Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

|

|

| Abbreviation | OSB |

|---|---|

| Motto | Ora et Labora (English: 'Pray and Work') |

| Formation | 529 |

| Founder | Benedict of Nursia |

| Founded at | Subiaco Abbey |

| Type | Catholic religious order |

| Headquarters | Sant'Anselmo all'Aventino |

|

Members

|

6,802 (3,419 priests) as of 2020[update] |

|

Abbot Primate

|

Gregory Polan, OSB |

|

Main organ

|

Benedictine Confederation |

|

Parent organization

|

Catholic Church |

The Benedictines, also known as the Order of Saint Benedict (or OSB), are a group of Christian monks and nuns in the Catholic Church. They follow a special set of rules called the Rule of Saint Benedict. People sometimes call them the Black Monks because of the dark clothes they wear. This group was started in the year 529 by Benedict of Nursia, a monk who created the rules they live by.

Even though they are called an "order," Benedictines don't have one single leader or a main headquarters that controls everything. Instead, each Benedictine monastery is independent and runs itself. They do have an international group called the Benedictine Confederation. This group was formed in 1893 to help all the different monasteries work together. They choose an Abbot Primate to represent them to the Vatican and the rest of the world.

Contents

History of the Benedictines

The first monastery founded by Benedict of Nursia was in Subiaco, Italy, around 529. He later started the famous Abbey of Monte Cassino. Benedict didn't plan to create a large "order" with many monasteries under one leader. His rules meant that each community should be independent.

When Monte Cassino was attacked around 580, the monks went to Rome. This helped spread the knowledge of Benedict's way of life. Copies of Benedict's Rule survived, and around 594, Pope Gregory I spoke highly of it. Over time, Benedict's Rule became very popular and was adopted by many monasteries across Western Europe. This was largely thanks to the efforts of Benedict of Aniane.

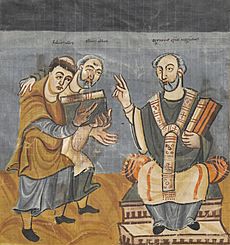

Monasteries and Books

From the 800s to the 1100s, monasteries were busy places where monks copied books by hand. This was called a scriptorium. The Bible was always the most important book. Monks who were good writers spent many hours each day copying texts. This was a very important job in the Middle Ages, as it helped preserve knowledge and stories.

In the Middle Ages, rich families often helped start monasteries. For example, Cluny Abbey was founded in 910. It was known for strictly following the Rule of Saint Benedict. The abbot (leader) of Cluny was in charge of all the smaller monasteries connected to it.

Over time, new groups of monks started, like the Camaldolese and the Cistercians. The Cistercians are sometimes called the "White Monks."

By the late 1100s, the Benedictine way of life became less dominant. New groups like the Franciscans and Dominicans became more popular. Benedictine monks promised to stay in one monastery for life. But the new groups could travel, which helped them connect with people in growing cities. Also, sometimes rich people would take control of monasteries' money, which hurt the communities.

Benedictines in England

The English Benedictine Congregation is the oldest group of Benedictine monasteries. Thanks to people like Wilfrid and Dunstan, the Benedictine Rule quickly spread in England. Many important churches and cathedrals were run by Benedictine monks. Monasteries also acted as hospitals and safe places for people who were sick or homeless. Monks studied plants and minerals to find ways to help people feel better.

During the English Reformation, all monasteries in England were closed, and their lands were taken by the King. Monks and nuns who wanted to continue their way of life had to leave the country. In the 1800s, English Benedictines were able to return to England.

Today, there are several Benedictine monasteries in England. For example, Minster in Thanet Priory is home to Benedictine nuns. Other famous abbeys include Downside Abbey, Douai Abbey, Ealing Abbey, and Worth Abbey. Prinknash Abbey was returned to the Benedictines in 1928 after being used by King Henry VIII.

Ampleforth Abbey in Yorkshire was founded in 1802. It even started a daughter house in the United States, Saint Louis Abbey.

As of 2015, the English Congregation has three abbeys for nuns and ten for monks. They have members in England, Wales, the United States, Peru, and Zimbabwe.

Monastic Libraries in England

The Rule of Saint Benedict says that monks should spend a lot of time reading holy books. Monks would read privately, and also publicly during church services and meals. Monasteries were important centers for learning. Monks and nuns were encouraged to read and pray according to the Benedictine Rule. During meals, one monk would read aloud while the others ate in silence.

Benedictine monks were not allowed to own personal items. So, they collected and kept sacred books in libraries for everyone to use. Books were kept in different places: in the sacristy for church services, in the rectory for public readings like sermons, and in the main library, which had the largest collection.

The first record of a monastic library in England was in Canterbury. To help Augustine of Canterbury with his mission, Pope Gregory I gave him nine books. Later, Theodore of Tarsus brought Greek books to Canterbury when he started a school there.

Benedictines in France

During the French Revolution, many Catholic Church institutions, including monasteries, were closed. Monasteries were allowed to form again in the 1800s. However, later in that century, laws were passed that made it hard for religious groups to teach. This led to Benedictine teaching monks being forced to leave France, a process that finished in 1901.

Benedictines in Germany

Saint Blaise Abbey in Germany's Black Forest was likely founded in the late 900s. It was influenced by reforms from other monasteries, especially those following the Cluny style. Saint Blaise Abbey then helped reform or found other monasteries in the region, including Muri Abbey and Göttweig Abbey.

Benedictines in Switzerland

Kloster Rheinau was a Benedictine monastery in Switzerland, founded around 778. The abbey of Our Lady of the Angels was founded in 1120.

Benedictines in the United States

The first Benedictine in the United States was Pierre-Joseph Didier, who arrived in 1790. The first Benedictine monastery was Saint Vincent Archabbey in Pennsylvania, founded in 1832 by Boniface Wimmer. He was a German monk who wanted to help German immigrants in America. Wimmer also started St. John's Abbey in Minnesota in 1856. By the time he died in 1887, he had sent Benedictine monks to many states.

Wimmer also asked for Benedictine nuns to come to America. In 1852, Sister Benedicta Riepp and two other sisters founded a community in St. Marys, Pennsylvania. They soon sent sisters to other states.

Swiss monks also came to America, founding St. Meinrad Archabbey in Indiana in 1854. They also spread to Arkansas and Louisiana, followed by Swiss sisters.

Today, there are over 100 Benedictine houses in America. Most belong to one of four main groups, like the American-Cassinese congregation, which includes 22 monasteries started by Boniface Wimmer.

Benedictine Vows and Daily Life

A strong sense of community has always been important for Benedictines. When someone joins a Benedictine community, they make a special promise. This promise includes staying with that community for life, living a monastic way of life, and obeying the community's leader. This is known as the "Benedictine vow."

The leaders of Benedictine monasteries, called abbots (for monks) and abbesses (for nuns), have full authority over their communities. They decide what duties people have, what books can be read, and how the community lives day-to-day.

Benedictines follow a strict daily schedule called the horarium. This schedule makes sure that time is used well for prayer, work, meals, spiritual reading, and sleep. The Benedictine motto, Ora et Labora, means "Pray and Work," which sums up their way of life.

While Benedictines don't take a vow of silence, they have specific times for strict silence. At other times, they try to be as quiet as possible. Social conversations are usually limited to special recreation times. Each Benedictine house has its own 'customary,' which explains how they adapt the Rule of Saint Benedict to their specific needs.

In the Catholic Church, Benedictine monasteries are considered "religious institutes." Their members are part of the "consecrated life." While many Benedictine monks are not priests, some can be ordained.

Some monasteries are very active in their communities, running schools or parishes. Others focus more on quiet prayer and work within their monastery walls.

Benedictines also played a role in the development of spas. Their rules included practices for cleanliness and encouraged therapeutic bathing.

How Benedictines are Organized

Benedictine monasteries are different from many other religious orders. Each Benedictine house is independent and led by its own abbot or abbess. They don't have a single leader who controls all monasteries worldwide.

However, in modern times, different groups of independent monasteries have formed "congregations" (like the Cassinese or English Congregations). These congregations are part of the Benedictine Confederation, which was created by Pope Leo XIII in 1893. The Confederation has an Abbot Primate who represents all Benedictines to the Vatican and the world. The main office for the Benedictine Confederation is in Rome, Italy.

In 1313, Bernardo Tolomei started the Order of Our Lady of Mount Olivet. This community also follows the Rule of Saint Benedict and is part of the Benedictine Confederation.

Other Groups Following the Rule

The Rule of Saint Benedict is also used by other religious orders that started as reforms of the Benedictine tradition. Examples include the Cistercians and Trappists. These groups are separate from the Benedictine Confederation.

While Benedictines are traditionally Catholic, some communities in the Anglican Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, and Lutheran Church also follow the Rule of Saint Benedict.

Famous Benedictines

Many people have been part of the Benedictine order throughout history. Here are some of the most well-known:

Saints and Blesseds

- Boniface (around 680–755)

- Willibrord (around 658–739)

- Rupert of Salzburg (c. 660–710)

- Suitbert of Kaiserwerdt (d. 713)

- Sturm (c. 705–79)

- Ansgar (801–65)

- Wolfgang of Regensburg (934–994)

- Adalbert of Prague (c. 956 – 997)

- Gerard of Csanád (c. 980 – 1046)

- Pope Gregory VII (c. 1020 – 1085)

- Pope Victor III (c. 1026–87)

- Pope Celestine V (1215–96)

- Pope Urban V (1310–70)

- Ambrose Barlow (1585–1641)

- Pope Pius VII (1742–1823)

Popes

- Pope Sylvester II (c. 946–1003)

- Pope Paschal II (d. 1118)

- Pope Gelasius II (d. 1119)

- Pope Clement VI (1291–1352)

- Pope Gregory XVI (1765–1846)

Founders of Abbeys and Reformers

- Earconwald (c. 630 – 693)

- Benedict Biscop (c. 628 – 690)

- Leudwinus (c. 665 – 713)

- Benedict of Aniane (747–821)

- Berno of Cluny (c. 850 – 927)

- Odo of Cluny (c. 878 – 942)

- Majolus of Cluny (c. 906 – 94)

- Odilo of Cluny (c. 962 – c. 1048)

- Walter of Pontoise (c. 1030 – c. 1099)

- Bernard of Cluny (d. 1109)

- Peter the Venerable (c. 1092 – 1156)

- Romuald (c. 956 – c. 1026)

- Robert of Molesme (c. 1028 – 1111)

- Alberic of Cîteaux (d. 1109)

- Stephen Harding (d. 1134)

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153)

- William of Hirsau (c. 1030 – 91)

- John Gualbert (995–1073)

- Stephen of Obazine (1084–1154)

- Robert of Arbrissel (c. 1045 – 1116)

- William of Montevergine (1085–1142)

- Nicholas Justiniani (fl. 1153–1179)

- Sylvester Gozzolini (1177–1267)

- Bernardo Tolomei (1272–1348)

- Laurent Bénard (1573–1620)

- Prosper Guéranger (1805–1875)

- Jean-Baptiste Muard (1809–1854)

- Boniface Wimmer (1809–1887)

- Maurus Wolter (1825–1890)

- Martin Marty (1834–1896)

- Andreas Amrhein (1844–1927)

- Lambert Beauduin (1873–1960)

- Anscar Vonier (1875–1938)

- Margit Slachta (1884–1974)

Scholars, Historians, and Writers

- Jonas of Bobbio (600–659)

- Bede (673–735)

- Aldhelm (c. 639 – 709)

- Alcuin (d. 804)

- Rabanus Maurus (c. 780 – 856)

- Paschasius Radbertus (785–865)

- Ratramnus (d. 866)

- Walafrid Strabo (c. 808 – 49)

- Notker Labeo (c. 950 – 1022)

- Guido of Arezzo (991–1050)

- Hermann of Reichenau (1013–54)

- Paul the Deacon (c. 720 – 99)

- Hincmar (806–82)

- Maurus of Pécs (c. 1000 – c. 1075)

- Peter Damian (c. 1007 – 1072)

- Lanfranc (c. 1005 – 1089)

- Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033 – 1109)

- Eadmer (c. 1060 – c. 1126)

- Florence of Worcester (d. 1118)

- Symeon of Durham (d. 1130)

- Jocelyn de Brakelond (d. 1211)

- Matthew Paris (c. 1200 – 1259)

- William of Malmesbury (c. 1095 – c. 1143)

- Gervase of Canterbury (c. 1141 – c. 1210)

- Roger of Wendover (d. 1236)

- Peter the Deacon (d. 1140)

- Adam Easton (d. 1397)

- Honoré Bonet (c. 1340 – c. 1410)

- John Lydgate (c. 1370 – c. 1451)

- John Whethamstede (d. 1465)

- Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516)

- Louis de Blois (1506–66)

- Benedict van Haeften (1588–1648)

- Augustine Baker (1575–1641)

- Anthony Batt (d. 1651)

- Jean Mabillon (1632–1707)

- Mariano Armellino (1657–1737)

- Antoine Augustin Calmet (1672–1757)

- Magnoald Ziegelbauer (1689–1750)

- Marquard Herrgott (1694–1762)

- Luigi Tosti (1811–97)

- Jean Baptiste François Pitra (1812–89)

- Oswald William Moosmuller (1842–1901)

- Suitbert Bäumer (1845–94)

- Francis Aidan Gasquet (1846–1929)

- Fernand Cabrol (1855–1937)

- Germain Morin (1861–1946)

- Henri Quentin (1872-1935)

- John Chapman (1865–1933)

- Cuthbert Butler (1858–1934)

Maurists

These were Benedictine scholars from a French group known for their learning:

- Nicolas-Hugues Ménard (1585–1644)

- Luc d'Achery (1609–85)

- Antoine-Joseph Mège (1625–91)

- Thierry Ruinart (1657–1709)

- François Lamy (1636–1711)

- Pierre Coustant (1654–1721)

- Edmond Martène (1654–1739)

- Ursin Durand (1682–1771)

- Bernard de Montfaucon (1655–1741)

- René-Prosper Tassin (1697–1777)

Bishops and Martyrs

- Ernest (d. 1148)

- Laurence of Canterbury (d. 619)

- Mellitus (d. 624)

- Justus (d. 627)

- Paulinus of York (d. 644)

- Leudwinus (c. 665 – 713)

- Oda of Canterbury (d. 958)

- Bertin (c. 615 – c. 709)

- Wilfrid (c. 633 – c. 709)

- Cuthbert (c. 634 – 687)

- John of Beverley (d. 721)

- Swithun (d. 862)

- Æthelwold of Winchester (d. 984)

- Edmund Rich (1175–1240)

- Abbot Suger (c. 1081 – 1151)

- John Beche (d. 1539)

- Richard Whiting (d. 1539)

- Hugh Cook Faringdon (d. 1539)

- Sigebert Buckley (c. 1520 – c. 1610)

- John Roberts (1577–1610)

- Gabriel Gifford (1554–1629)

- Alban Roe (1583–1642)

- Philip Michael Ellis (1652–1726)

- Charles Walmesley (1722–97)

- William Placid Morris (1794–1872)

- John Polding (1794–1877)

- William Bernard Ullathorne (1806–89)

- Roger Vaughan (1834–83)

- Guglielmo Sanfelice d'Acquavilla (1834–1897)

- Joseph Pothier (1835–1923)

- John Cuthbert Hedley (1837–1915)

- Domenico Serafini (1852–1918)

- Placidus Nkalanga (1918–2015)

Twentieth Century Benedictines

- Lambert Beauduin (1873–1960)

- Alfredo Schuster (1880–1954)

- Bede Griffiths (1906–1993)

- Paul Augustin Mayer (1911–2010)

- Hans Hermann Groër (1919–2003)

- Basil Hume (1923–1999)

- Rembert Weakland (1927–2022)

- Daniel M. Buechlein (1938–2018)

- Jerome Hanus (1940-)

- Anselm Grün (1945–)

- Knut Ansgar Nelson (1906–1990)

Nuns

- Scholastica (c. 480 – 547)

- Æthelthryth (c. 636 – 679)

- Hilda of Whitby (c. 614 – 680)

- Werburh (d. 699)

- Mildrith (d. early 7th century)

- Walpurga (c. 710 – 779)

- Wulfthryth of Wilton (c. 937 – 1000)

- Edith of Wilton (c. 961 – 984)

- Cunigunde of Luxembourg (c. 975 – 1040)

- Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179)

- Gertrude the Great (1256 – c. 1302)

- Joan Chittister (1936–)

- Thomas Welder (1940–2020)

- Noella Marcellino (1951–)

- Teresa Forcades (1966–)

Oblates

Benedictine Oblates are people who live in the world but try to follow the spirit of the Benedictine way of life. They are connected to a specific monastery.

- Emperor Henry II (972–1024)

- Frances of Rome (1384–1440)

- Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848–1907)

- Jacques Maritain (1882–1973)

- Romano Guardini (1885–1968)

- Dorothy Day (1897–1980)

- Walker Percy (1916–1990)

- Kathleen Norris (1947– )

See also

In Spanish: Orden de San Benito para niños

In Spanish: Orden de San Benito para niños

- Dom Pierre Pérignon

- Benedictine Confederation

- Catholic religious order

- Cistercians

- French Romanesque architecture

- Sisters of Social Service

- Trappists

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |