Dorothy Day facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Servant of GodDorothy Day OblSB |

|

|---|---|

Day in 1916

|

|

| Born | November 8, 1897 New York City, U.S. |

| Hometown | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | November 29, 1980 (aged 83) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Cemetery of the Resurrection, New York City |

Dorothy Day (born November 8, 1897 – died November 29, 1980) was an American writer and social activist. She spent her early life exploring different ideas and ways of living. Later, she became a Catholic but continued her work for social justice and peace. Many people saw her as a leading voice for change among American Catholics.

Dorothy Day wrote about her journey to faith in her 1952 book, The Long Loneliness. She was also a busy journalist, using her writing to share her ideas about helping others. In 1917, she was arrested for joining Alice Paul's nonviolent group, the Silent Sentinels, who protested for women's right to vote. In the 1930s, Day worked with Peter Maurin to start the Catholic Worker Movement. This group believed in pacifism (peace, not war) and offered direct help to poor and homeless people. They also took part in peaceful protests. Dorothy Day was arrested several times for her peaceful actions, even when she was 75 years old.

As part of the Catholic Worker Movement, Day helped start the Catholic Worker newspaper in 1933. She was its editor until she died in 1980. In the newspaper, Day wrote about a Catholic idea called distributism. She saw this as a middle way between capitalism (where businesses are owned by individuals) and socialism (where the government controls many things). Pope Benedict XVI used her story as an example of finding faith in a modern world. Pope Francis also mentioned her to the United States Congress as one of four great Americans who helped build a better future.

The Catholic Church is now looking into whether Dorothy Day could become a saint. Because of this, the Church calls her a Servant of God.

Biography

Early Life and Learning

Dorothy May Day was born on November 8, 1897, in Brooklyn, New York. Her family was middle-class and patriotic. Her father, John Day, was a sportswriter. In 1904, his job moved the family to California. After the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 destroyed his newspaper, they moved to Chicago. Dorothy learned an important lesson from how people helped each other after the earthquake. She saw how neighbors sacrificed for one another in a crisis.

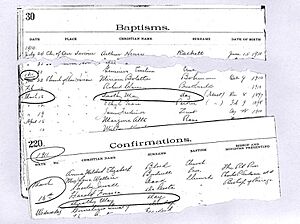

Dorothy's parents didn't go to church often, but Dorothy was very religious as a child. She read the Bible a lot. When she was ten, she started going to an Episcopal church in Chicago. She loved the church's services and music. She was baptized and confirmed there in 1911.

As a teenager, Dorothy loved to read. She especially liked books about social issues, like The Jungle by Upton Sinclair. She also read about anarchism from Peter Kropotkin. He believed that people could create a free society through cooperation and helping each other. She also enjoyed Russian literature. These books helped her understand and support social activism. Dorothy finished high school in 1914.

In 1914, Dorothy went to the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign on a scholarship. She mostly read books about Christian social ideas. She didn't join campus social groups and supported herself by buying clothes from discount stores. After two years, she left the university and moved to New York City.

Becoming an Activist

Dorothy settled in the Lower East Side of New York. She worked for several Socialist newspapers, like The Liberator and The Masses. She believed in peace, even in conflicts between social classes. She felt pulled in different directions by various ideas like Socialism, Syndicalism, and Anarchism.

In November 1917, she was arrested for protesting outside the White House. She was part of the Silent Sentinels campaign, which fought for women's right to vote. She was sentenced to 30 days in jail but was released after 15 days, during which she went on a hunger strike.

Dorothy lived in Greenwich Village and became friends with many writers and activists. She was close to Eugene O'Neill, who she said helped her feel more religious. She also knew important American Communists like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.

In 1924, she wrote a book called The Eleventh Virgin. It was partly about her own life and how women tried to find freedom. She later called it a "very bad book." With money from selling the movie rights, she bought a beach cottage on Staten Island, New York. There, she met Forster Batterham, a biologist and activist.

Dorothy was very happy when she became pregnant in 1925. Batterham, however, did not want to be a father. While she was away visiting her mother, Dorothy started exploring Catholicism more deeply. After her daughter, Tamar Teresa, was born in March 1926, Dorothy had her baby baptized in July 1927. Batterham did not like her growing religious faith. Their relationship ended, and Dorothy was baptized into the Catholic Church in December 1927.

In 1929, Dorothy moved to Los Angeles for a job writing movie dialogue. After the 1929 stock market crash, she lost her job. She returned to New York and worked as a journalist, writing for local papers and Catholic publications.

In 1932, she went to Washington D.C. to report on a "Hunger March." This experience made her want to do more for social justice. She prayed at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception to find a way to use her talents to help poor workers.

Starting the Catholic Worker Movement

In 1932, Dorothy Day met Peter Maurin. She always said he was the true founder of the Catholic Worker Movement. Maurin was a French immigrant who had studied to be a religious brother. He had strong ideas about social justice and helping the poor, inspired by St. Francis of Assisi. He also knew a lot about Catholic teachings on social issues. Maurin helped Dorothy understand how her desire for social action fit with Catholic beliefs.

The Catholic Worker Movement began on May 1, 1933, when the Catholic Worker newspaper was first published. It cost one cent and has been published ever since. It was for people suffering during the Great Depression, telling them that the Catholic Church had a plan to help. The newspaper did not have ads and its staff were not paid.

The Catholic Worker newspaper reported on strikes and working conditions, especially for women and African American workers. It also explained Catholic teachings on social issues. It encouraged readers to take action, like supporting unions. The newspaper's support for child labor laws sometimes caused disagreements with Church leaders.

The main competitor to the Catholic Worker was the Communist Daily Worker. Dorothy Day disagreed with the Communists' atheism and their belief in violent revolution. The Catholic Worker asked, "Is it not possible to be radical and not atheist?" Dorothy defended government programs that helped the poor, which the Communists made fun of. The Church leaders supported Dorothy's movement. Many Catholic writers joined the Catholic Worker, including Michael Harrington and Thomas Merton.

From the newspaper, the movement grew to include "houses of hospitality" (shelters providing food and clothing) and farms for communal living. The movement quickly spread across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. By 1941, over 30 Catholic Worker communities had started.

In 1935, the Catholic Worker began to strongly support pacifism, which meant they did not believe in war, even when the Church traditionally allowed for "just wars." This was especially difficult during the Spanish Civil War. Dorothy Day refused to support Francisco Franco, even though many Catholic leaders did. She believed in preparing for peace, not war. She wrote, "We must prepare now for martyrdom – otherwise, we will not be ready." Because of her stance, the newspaper's circulation dropped from 150,000 to 30,000.

In 1938, she published From Union Square to Rome, explaining how her activism became connected to her faith. She wrote about her journey to accept the Catholic faith.

Continuing Her Activism

In the early 1940s, Dorothy became connected with the Benedictines. In 1955, she became an oblate of St. Procopius Abbey. This gave her a spiritual practice that supported her for the rest of her life.

When the U.S. entered World War II in 1941, Dorothy reaffirmed her pacifism. She urged people not to support the war. Her January 1942 column was titled "We Continue Our Christian Pacifist Stand." She wrote that they would try to be peacemakers and would not take part in armed warfare or make weapons. She also said, "We love our country, and we love our President." The circulation of the Catholic Worker dropped again, and many houses of the movement closed as people joined the war effort.

In 1949, workers at cemeteries in New York went on strike. Cardinal Francis Spellman used seminary students to dig graves and called the strike "Communist-inspired." Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker staff joined the strikers. Dorothy wrote to Spellman, defending the workers' right to form a union and their "dignity as men." She asked him to resolve the conflict. The strike ended in March, and Dorothy wrote that it was a "temptation of the devil" for clergy and ordinary people to fight each other.

In 1951, the Archdiocese of New York told Dorothy to stop publishing or remove the word "Catholic" from her newspaper's name. She politely refused, saying she had as much right to publish as other Catholic groups. The Archdiocese did not take further action.

Her autobiography, The Long Loneliness, was published in 1952. It told the story of her life, from her early days to becoming a co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement.

From 1955 to 1960, Dorothy Day joined pacifists in refusing to take part in civil defense drills. These drills were meant to prepare for nuclear attacks. Dorothy saw her refusal as a way to do "public penance" for the U.S. using the first atomic bomb. She was arrested several times but often not jailed, as judges didn't want to make her a "martyr." One time, she did serve 30 days in jail.

In 1960, she praised Fidel Castro's "promise of social justice" in Cuba. She visited Cuba and wrote about her experiences in the Catholic Worker. She was interested in the religious life of the people and also saw how the government was trying to improve life for them.

Dorothy hoped the Second Vatican Council (a major meeting of Catholic leaders) would support nonviolence and speak out against nuclear weapons. She spoke to bishops in Rome and joined a ten-day fast. She was happy when the Council's document, Gaudium et spes (1965), said that nuclear warfare was not compatible with traditional Catholic teachings.

Her book about the Catholic Worker Movement, Loaves and Fishes, was published in 1963.

Dorothy had mixed feelings about the 1960s counterculture. She liked that some people called her the "original hippie" because she didn't care about material things. But she also thought some hippies were self-centered. She continued to lead the Catholic Worker houses, even though she didn't have direct control over them.

In 1966, Cardinal Spellman visited U.S. troops in Vietnam and said the war was "for civilization." Dorothy wrote a response in the Catholic Worker, asking why Americans were fighting in so many places around the world.

In 1970, during the Vietnam War, she described Ho Chi Minh as a "man of vision" and a "patriot." She always tried to find common ground with people, even those she disagreed with.

Later Years and Death

In 1971, Dorothy Day received the Pacem in Terris Award for her work for peace. The University of Notre Dame gave her its Laetare Medal in 1972. She also received the Poverello Medal in 1976.

Despite poor health, Dorothy visited India and met Mother Teresa. In 1971, she visited Eastern European countries and the Soviet Union as part of a peace group. She met with writers and defended Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a writer who was being harassed in his own country.

In 1972, the Jesuit magazine America dedicated an entire issue to Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement for her 75th birthday. They said she symbolized the best of American Catholicism.

Dorothy had supported Cesar Chavez's efforts to organize farm workers in California since the mid-1960s. In 1973, she joined Chavez in his campaign and was arrested for protesting. She spent ten days in jail.

In 1974, she received the Isaac Hecker Award for her commitment to building a more just and peaceful world.

Dorothy Day made her last public appearance at a Catholic event in Philadelphia in 1976. She spoke about peace and criticized the event for honoring the military on August 6, which was the day the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

Dorothy Day died of a heart attack on November 29, 1980, at Maryhouse in Manhattan. She was buried in the Cemetery of the Resurrection on Staten Island. Her gravestone says Deo gratias (Thanks be to God). Her daughter, Tamar, and Tamar's father, Forster Batterham, attended her funeral. Dorothy and Batterham remained friends throughout their lives.

Beliefs

Helping the Poor

Dorothy Day often wrote about poverty. She admired government efforts to help people, but she believed that personal acts of charity were also very important. She felt that helping others should come from the heart.

She also spoke out against actions that harmed the poor. She said that "depriving the laborer" was a serious wrong. She also criticized advertising that made people want things they didn't need, saying it could make the poor "sell their liberty and honor."

Views on Social Security

Dorothy Day did not support Social Security. In 1945, she wrote that it was a "great defeat for Christianity." She believed it forced people to help others, rather than choosing to do so out of kindness. She felt that businesses should take care of their workers, and if they didn't, the state had to step in. She thought this showed that big businesses had failed.

Anarchism and Cooperation

Dorothy Day learned about anarchism in college. She read about anarchists like Peter Kropotkin, who believed in cooperation and mutual aid. She also attended anarchist events. She was very sad when anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in 1927. She felt a connection with them, seeing how everyone is connected, like the idea of the Body of Christ in Catholicism.

She wasn't afraid to use the word "anarchism" for herself. She said that anarchists accepted her because she had been arrested many times for her protests and had never voted. But they were confused by her strong faith in the Catholic Church. Dorothy, in turn, saw Christ in them, even if they didn't believe in Him, because they were working to help the poor.

Views on Communism

In the early days of the Catholic Worker, Dorothy Day explained how her ideas differed from communism. She believed in widespread private property and individuals owning their land and tools. She was against "finance capitalism" (big, powerful corporations) but thought there could be a "Christian capitalism" or "Christian Communism." She said that while both Communism and Christianity cared for the poor, Communism wanted to make the poor richer, but Christianity wanted to make the rich humble and the poor holy.

In 1949, she explained why she protested when some Communists were denied bail. She said she had loved the people she worked with in the Communist movement and learned from them. She felt they helped her find God in the poor, even more than she had in Christian churches. She agreed with some Communist ideas, like "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need" and the idea of the "withering away of the State" (where the government would become less powerful). But she disagreed with their methods, especially violence. She believed that Christians should be pacifists and use "works of mercy" as their actions.

Regarding Fidel Castro's Cuba, she wrote in 1961 that she was "on the side of the revolution." She believed in new ideas about property, like farming communes and cooperatives. She wrote, "God bless Castro and all those who are seeing Christ in the poor."

Church Property

Dorothy Day believed in "smallness" and simplicity. She thought this applied to the Catholic Church's property too. She was glad that the Papal States (lands ruled by the Pope) were taken from the Church in the past. She believed that if people and the Church couldn't fix economic problems, God would step in.

Some critics, like Jesuit priest Daniel Lyons, said Dorothy Day sometimes simplified things too much and "distorted" the Pope's views.

Catholic Faith

Dorothy Day was very committed to her Catholic faith. She once told a Communist writer who asked how she could believe in things like the Immaculate Conception and the Resurrection: "I believe in the Roman Catholic Church and all she teaches. I have accepted Her authority with my whole heart." She saw faith as a gift from God.

Her commitment to Church rules was clear. Once, when a priest was about to celebrate Mass without the proper robes, Dorothy insisted he put them on. When he complained about the rules, she said, "On this farm, we obey the laws of the Church."

Contributions to Feminism

Helping the Oppressed

Dorothy Day's early work was very radical and focused on helping individuals and promoting social change. Even though she didn't always call herself a feminist, her work fits with feminist ideas. She fought against unfair systems and worked for the rights of oppressed people. Her lifelong support for the disadvantaged was feminist in nature. She helped poor communities, supported activists, and worked to fix injustices within Catholicism. Her beliefs didn't change when she became Catholic; instead, her faith made her even more determined to fight for equality.

Dorothy Day helped create a place for feminist ideas in a religious world where women's experiences were often ignored. She considered how gender, race, and class affected people in her writing and work. This helped create religious ideas that truly reflected the experiences of all people in the Church. Through her actions, Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement aligned with feminist principles. She lived through important times for feminism, like the fight for women's right to vote and movements for equality in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. She always stuck to the Church's teachings about the importance of human life from beginning to end.

Writing About Life

Dorothy Day wrote constantly throughout her life, keeping journals and writing for herself. She published several books about her life: The Eleventh Virgin, From Union Square to Rome, The Long Loneliness, and Loaves and Fishes. These books together tell the story of her life. Writing autobiographies, especially by women, can be seen as a feminist act because it shares women's stories and experiences directly.

The Eleventh Virgin, published in 1924, was her first autobiography. It told the story of a young woman's experiences that mirrored Dorothy's own youth. Dorothy later regretted this book because it showed her early life before she became Catholic, which she no longer felt represented her. However, it was unusual at the time for a woman to write so openly about her early experiences.

Rejecting Gender Roles

Dorothy Day was known for challenging traditional gender roles in her work, politics, and the Catholic Church. From a young age, her father tried to prevent her from being hired as a journalist because she was a woman. She started as an "office girl," a job that fit what her family and the Church thought was proper for women. She was told to "write like a woman," simply and clearly. But she developed her writing, focusing on women's and social issues from her own perspective. She rejected the idea that women should only write about certain topics.

She wanted to be a journalist and do the work of a man, like joining protests and going to jail, to make her mark on the world. She questioned how much of this was ambition and how much was self-seeking.

Radical Catholic Ideas

Dorothy Day is most remembered for her radical Catholic social activism. During the Second Vatican Council, a major meeting of the Catholic Church, Dorothy and the Catholic Worker Movement traveled to Rome. They wanted to convince the Pope and the council to reject the "just war" idea and support pacifism and not fighting in wars, based on Christian values. They also wanted them to speak out against nuclear weapons.

With the Catholic Worker Movement, Dorothy first focused on workers' rights and helping the poor. Eventually, she called for a non-violent change against the industrial economy, militarism, and fascism. She strongly believed that non-violence, pacifism, and anarchism, combined with Christianity, would lead to a new and better society. The American government noticed her fight against the system. The FBI watched the Catholic Worker Movement from 1940 to 1970, and Dorothy was jailed four times during this period.

Dorothy Day's involvement with the Catholic Worker and her commitment to liberation theology (a way of understanding faith that focuses on helping the poor and oppressed) aligns with feminist values. She fought for social and political equality for everyone, no matter their race, gender, or class. Her efforts against the Catholic Church and the military state helped promote equality and relieve the suffering of the oppressed.

Working for Social Justice

Throughout her life, Dorothy Day was concerned about how powerful people affected ordinary people. This concern is shared by both liberation theology and feminist ideology. Dorothy called for a shift towards anarchism, communism, and pacifism, all based on Christian teachings. Her main tool against unfair systems was her writing and her voice.

Dorothy wrote about important events like wars, labor strikes, and military drafts. Her goal was to highlight social injustices and speak for those who couldn't speak for themselves. She wanted to start a movement to fix problems and prevent future oppression. Her advocacy and charity were especially important during difficult times in American history, like the Great Depression, when the Catholic Worker Movement began.

Legacy

Dorothy Day's papers are kept at Marquette University, along with many records of the Catholic Worker Movement. Her diaries and letters have been published.

Sadly, attempts to save her beach cottage on Staten Island failed in 2001. Developers tore it down just as it was about to be declared a historic landmark. Now, several large homes stand where her cottage once was.

In 1983, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops recognized Dorothy Day's role in making non-violence a Catholic principle. In 2013, Pope Benedict XVI spoke about Dorothy Day as an example of someone who found faith in a modern world.

On September 24, 2015, Pope Francis spoke to the United States Congress. He mentioned Dorothy Day as one of four great Americans, along with Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and Thomas Merton. He said her activism and passion for justice were inspired by her faith.

Films About Dorothy Day

An independent film called Entertaining Angels: The Dorothy Day Story was released in 1996. Moira Kelly played Dorothy Day, and Martin Sheen played Peter Maurin. A documentary called Dorothy Day: Don't Call Me a Saint came out in 2005. Another film, Revolution of the Heart: The Dorothy Day Story, aired on PBS in 2020.

Music About Dorothy Day

A song called "Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin" was released in 2016. In 2021, it was reported that this song was included in materials sent to the Vatican as part of the process for Dorothy Day to become a saint.

Honors and Recognition

- In 1992, Dorothy Day received the Courage of Conscience Award.

- In 2001, she was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York.

- Several university dormitories and campus ministry centers are named in her honor, including at Lewis University, the University of Scranton, Loyola University Maryland, and Xavier University.

- A professorship at St. John's University School of Law is named after her.

- At Marquette University, a dormitory floor is reserved for students interested in social justice, bearing her name.

- Saint Peter's University named its Political Science Office the Dorothy Day House.

- A supportive housing building in New York City, the Dorothy Day Apartment Building, opened in 2003.

- The DC Comics character Leslie Thompkins is based on Dorothy Day.

- The Dorothy Day Center in Saint Paul, Minnesota, is a homeless shelter managed by Catholic Charities.

- One of the new Staten Island ferries is named the Dorothy Day.

- Sacred Heart University has a residence hall named Dorothy Day Hall.

- The University of Notre Dame has a room in Geddes Hall, home of the Center for Social Concerns, named for Dorothy Day.

- Manhattan College started a Dorothy Day Center for the Study and Promotion of Social Catholicism in 2022.

Path to Sainthood

The idea for Dorothy Day to become a saint was first suggested publicly in 1983. In March 2000, Pope John Paul II allowed the Archdiocese of New York to begin the process. This means she can now be called a "Servant of God" by the Catholic Church. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops supported this in 2012. In 2015, Pope Francis praised Dorothy Day to the U.S. Congress.

Currently, the process for Day's sainthood has moved from the local (diocesan) stage to the Roman stage. In December 2021, the Archdiocese of New York sent all the collected evidence of Dorothy Day's holiness to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in Rome. The next steps involve the Vatican reviewing this evidence and documenting two miracles attributed to her.

Some members of the Catholic Worker Movement believe that making Dorothy Day a saint goes against her own values. However, others, including her granddaughter Martha Hennessy, are actively working towards her sainthood.

See also

In Spanish: Dorothy Day para niños

In Spanish: Dorothy Day para niños

- List of peace activists

- Catholic social teaching

- Christian anarchism

- Christian pacifism

- Christian politics

- Christian socialism

- Distributism

- Mutualism (economic theory)

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |