The Masses facts for kids

| First issue | 1911 |

|---|---|

| Final issue | 1917 |

| Country | United States |

| OCLC | 1756843 |

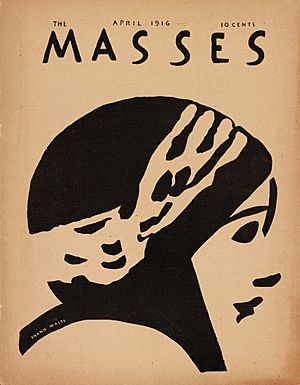

The Masses was a special magazine published every month in the United States from 1911 to 1917. It was known for its amazing artwork and its focus on socialist ideas. These ideas are about making society fairer for everyone.

The magazine had to stop publishing in 1917. This happened because the government said its editors were trying to stop people from joining the army during World War I. After The Masses closed, it was followed by other magazines like The Liberator and New Masses. Many famous writers and artists of that time, like Max Eastman and John Reed, shared their stories, poems, and art in The Masses.

Contents

A Magazine for Change

How The Masses Started

A unique Dutch immigrant named Piet Vlag started The Masses in 1911. For its first year, a kind supporter named Rufus Weeks paid for the magazine's printing. Piet Vlag wanted the magazine to be run by everyone who worked on it, but this idea didn't quite work out. After a few issues, he left.

However, his dream of an illustrated magazine about socialist ideas had already attracted young artists and writers. Many of these creative people lived in Greenwich Village, a famous artsy neighborhood in New York City. They included artists from the Ashcan School, like John French Sloan.

These artists and writers asked Max Eastman, who was studying at Columbia University, to be their editor. In August 1912, they sent him a short letter: "You are elected editor of The Masses. No pay."

In the very first issue he edited, Max Eastman wrote about what the magazine stood for:

A Free Magazine — This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers — There is a field for this publication in America. Help us to find it.

This meant The Masses wanted to be a free and honest magazine. It aimed to print truths that other money-focused newspapers might avoid. It wanted to challenge old ideas and not care what "important" people thought.

The Masses was closely connected to the art scene in New York City. It was different from other socialist newspapers, like the Appeal to Reason, which was printed in a small town in Kansas. The Masses was part of the lively, creative spirit of Greenwich Village.

The magazine had a special place among American left-wing publications. It supported new ideas like women's right to vote. But it also criticized other left-wing magazines for not being radical enough.

Challenges and Court Cases

After Max Eastman became editor, especially after 1914, The Masses often spoke out strongly against World War I. In September 1914, Eastman wrote that the war was like a "gambler's war." He believed it was caused by business interests and would not have a true winner.

By May 1916, the magazine's strong opinions caused problems. Two big magazine distribution companies stopped selling it. It was also banned from Canadian mail, university libraries, and even New York City subway newsstands.

Lawsuits Against The Masses

In July 1913, Max Eastman wrote an article in The Masses. He said that the Associated Press (AP), a major news agency, was hiding and changing news. This was about a coal miners' strike in West Virginia. Eastman claimed the AP was favoring the mine owners.

The AP sued Eastman and Art Young, an artist for the magazine. They said the magazine had unfairly criticized them. Art Young had drawn a cartoon called "Poisoned at the Source." It showed the AP poisoning the news with "Lies" and "Hatred of Labor Organization."

Eastman and Young were arrested but later released. They faced the possibility of jail time. Many people supported them, including famous activists like Lincoln Steffens and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. After two years, the lawsuits were quietly dropped.

Government Trials

In 1917, the United States passed the Espionage Act. This law made it illegal to say things that might hurt the war effort. The Masses tried to follow the new rules so it could still be sent through the mail. However, the government still stopped its mail.

The government then said the August 1917 issue had "treasonable material." Soon after, they brought charges against Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, John Reed, and other staff members. They were accused of trying to stop people from joining the military. If found guilty, they could face large fines and many years in prison.

The first trial began on April 15, 1918. The defendants were not too worried, even though the situation was serious. They even joked around in court. For example, when a band outside played "The Star-Spangled Banner" to sell war bonds, Merrill Rogers, the business manager, would jump up and salute the flag every time.

The judge, Learned Hand, told the jury that everyone has the right to their own opinions, even if they are socialist. After much discussion, the jury could not agree on a decision. This meant there was a "mistrial," and the case had to be tried again.

The second trial happened in September 1918. John Reed, who had been in Russia, came back to be there. The trial was very similar to the first one. The prosecutor gave a strong speech, saying the defendants should be punished for soldiers who died in the war. Art Young, who often slept during the trial, woke up and asked, "What? Didn't he die for me?" John Reed joked back, "Cheer up Art, Jesus died for you." Again, the jury could not agree, and it was another mistrial.

After The Masses closed, Max Eastman and others started a new magazine in March 1918. They called it The Liberator. The Masses continued to inspire people who wanted social change for many years.

Important People Who Wrote for The Masses

Many well-known writers and artists contributed to The Masses. Here are some of them:

- Sherwood Anderson

- Cornelia Barns

- George Bellows

- Louise Bryant

- George Creel

- Arthur B. Davies

- Dorothy Day

- Floyd Dell

- Max Eastman

- Wanda Gág

- Jack London

- Amy Lowell

- Mabel Dodge Luhan

- Inez Milholland

- Robert Minor

- Pablo Picasso

- John Reed

- Boardman Robinson

- Carl Sandburg

- John French Sloan

- Upton Sinclair

- Louis Untermeyer

- Mary Heaton Vorse

- Art Young

Magazine Topics

Focus on Workers' Rights

The Masses reported on many important labor struggles of its time. These included the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike of 1912 and the Ludlow Massacre. The magazine strongly supported workers' unions like the IWW and political leaders like Eugene V. Debs. It also followed the events after the Los Angeles Times bombing.

Stories and Book Reviews

Many leading writers of the time contributed to the magazine without pay. Sherwood Anderson was one of the most famous. The magazine's fiction editor, Floyd Dell, "discovered" Anderson. Anderson's stories in The Masses later became part of his famous book, Winesburg, Ohio.

The magazine's book review section was called "Books that Are Interesting." Floyd Dell wrote insightful reviews of many important books. These included novels by Theodore Dreiser and works by Carl Jung.

Artwork in The Masses

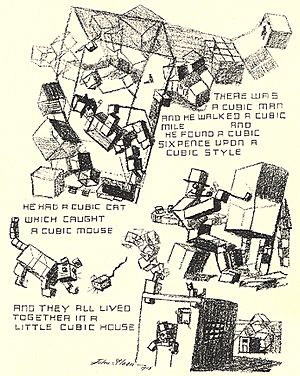

Even though modern art was becoming popular, The Masses mostly published realistic artwork. This style is now called the Ashcan School. Artists like Art Young, who was on the editorial board, used the term "ash can art." These artists wanted to show real life and create honest pictures. They often used a crayon technique that made their drawings look like quick sketches.

This style was common in The Masses from 1912 to 1916. However, it became less common after a "strike" by some artists in 1916. This happened when Max Eastman started to have more control over what was published. He sometimes printed things without asking the editorial board first.

One big issue was that Eastman and Floyd Dell added captions to many illustrations without the artists' permission. John Sloan was especially upset. He felt the magazine was losing its original purpose. Sloan and other artists left the magazine in 1916.

In its later years, the magazine started to feature more modern art. But it still kept some realistic illustrations. Some covers from 1916 and 1917 show this change. They featured stylish "cover girls" instead of crayon drawings of everyday scenes.

The Masses was also famous for its many political cartoons. Art Young and Robert Minor were well-known for these. Their cartoons were sometimes controversial. After the United States entered World War I, their anti-war cartoons were even seen as disloyal.

The illustrations in The Masses often promoted the magazine's socialist ideas. For example, John Sloan's drawings of working-class people supported labor rights. Alice Beach Winter's art showed the lives of mothers and working children. Maurice Becker's city scenes made fun of the rich. While many illustrations had a political message, Max Eastman also wanted to publish art just for its beauty. He wanted The Masses to combine revolutionary ideas with great literature and art.

See also

In Spanish: The Masses para niños

In Spanish: The Masses para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |