Charlotte Perkins Gilman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 3, 1860 Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | August 17, 1935 (aged 75) Pasadena, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

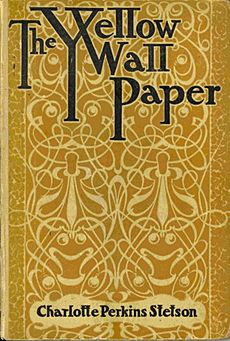

| Notable works | "The Yellow Wallpaper" Herland Women and Economics |

| Signature | |

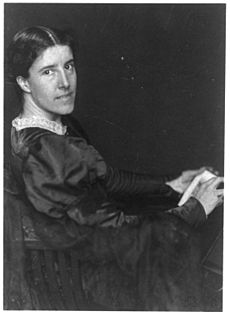

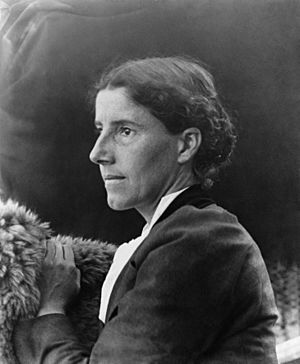

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (born Perkins; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935) was an American writer, lecturer, and social reformer. She also used her first married name, Charlotte Perkins Stetson. She was known for her unique ideas and lifestyle, especially about women's roles. She is recognized in the National Women's Hall of Fame. Her most famous work is the short story "The Yellow Wallpaper". She wrote this story after experiencing severe sadness and mental health struggles following the birth of her child.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was born on July 3, 1860, in Hartford, Connecticut. Her parents were Mary Perkins and Frederic Beecher Perkins. She had one older brother, Thomas Adie. Her father left the family when Charlotte was very young. This meant her childhood was often spent in poverty.

Because her mother struggled to support the family, Charlotte often stayed with her father's aunts. These included Isabella Beecher Hooker, who fought for women's right to vote. Another aunt was Harriet Beecher Stowe, who wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin. Her aunt Catharine Beecher was an important educator.

Charlotte's schooling was not regular. She went to seven different schools for only about four years in total, finishing when she was fifteen. Her mother was not very loving. She tried to protect her children by stopping them from making close friends or reading fiction. In her autobiography, Charlotte wrote that her mother only showed affection when she thought Charlotte was asleep.

Despite a lonely childhood, Charlotte prepared herself for the future. She often visited the public library and studied ancient civilizations on her own. Her father, who loved books, later sent her a list of books he thought she should read.

Much of Charlotte's youth was spent in Providence, Rhode Island. Most of her friends were boys, and she proudly called herself a "tomboy."

Her teachers were impressed by her intelligence and knowledge, even though she was not a top student. She especially liked "natural philosophy", which is now called physics. In 1878, at age eighteen, she studied at the Rhode Island School of Design. Her absent father helped pay for her studies. She then earned money by creating art for trade cards. She also tutored others and painted.

Adulthood and Personal Life

In 1884, Charlotte married the artist Charles Walter Stetson. She had first said no to his proposal because she felt it wasn't right for her. Their only child, Katharine Beecher Stetson, was born on March 23, 1885. After Katharine's birth, Charlotte experienced a very difficult period of sadness and mental health challenges. At that time, women's health issues were often misunderstood.

In 1888, Charlotte separated from her husband. This was very unusual in the late 1800s. They officially divorced in 1894. After their divorce, Charles Stetson married Charlotte's friend, Grace Ellery Channing. Charlotte moved to Southern California with her daughter Katharine and lived with Grace for a time.

After separating from her husband, Charlotte moved with her daughter to Pasadena, California. There, she became active in groups that worked for women's rights and social change. She wrote and edited the Bulletin, a journal for one of these groups.

In 1894, Charlotte sent her daughter Katharine to live with her former husband and his new wife, Grace. Charlotte wrote in her memoir that she was happy for them. She felt Katharine's "second mother was fully as good as the first." Charlotte also believed her ex-husband had a right to spend time with Katharine, and Katharine had a right to know her father.

After her mother passed away in 1893, Charlotte moved back to the East Coast. She reconnected with her first cousin, Houghton Gilman, a lawyer. They quickly became close and fell in love. They wrote letters to each other when Charlotte was on lecture tours. They married in 1900 and lived in New York City until 1922. Their marriage was very different from her first one.

In 1922, Charlotte moved to Houghton's old family home in Norwich, Connecticut. After Houghton suddenly died in 1934, Charlotte moved back to Pasadena, California, to be near her daughter.

In January 1932, Charlotte was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer. On August 17, 1935, she chose to end her life. In her autobiography and a note she left, she wrote that she "chose chloroform over cancer" and died quickly.

Career as a Writer and Speaker

Charlotte Perkins Gilman became very active in social reform movements after moving to Pasadena. In 1896, she represented California at important meetings. These included the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in Washington, D.C., and a large international meeting in London.

In 1890, she discovered the Nationalist Clubs movement. This group wanted to end "capitalism's greed" and differences between social classes. Her poem "Similar Cases," published in Nationalist magazine, made fun of people who resisted social change. Critics liked it. That same year, she wrote many essays, poems, a novella, and her famous short story The Yellow Wallpaper.

Her career really took off when she started giving talks about Nationalism. Her first book of poems, In This Our World, came out in 1893. As a popular speaker, she earned money from her talks. Her fame grew, and she met many other activists and writers who supported the feminist movement.

The Yellow Wallpaper

In 1890, Charlotte Gilman wrote her short story "The Yellow Wallpaper". It is now a very popular book published by the Feminist Press. She wrote it quickly in June 1890 at her home in Pasadena. It was printed about a year and a half later in the January 1892 issue of The New England Magazine.

This story has been included in many collections of women's literature and American literature. The story is about a woman who struggles with her mental health. Her husband, who is also her doctor, keeps her confined to a room for her health. She becomes obsessed with the room's strange yellow wallpaper.

Gilman wrote this story to show how women's lack of freedom affected their mental and emotional well-being. She wanted to change how people thought about women's roles in society. The story was inspired by her own difficult experience with a doctor who tried to cure her sadness with a "rest cure". In the story, the main character must follow her husband's orders, even though what she really needs is mental activity and freedom. Gilman even sent a copy of the story to the doctor who had treated her.

Other Important Writings

Gilman's first book was Art Gems for the Home and Fireside (1888). But her collection of satirical poems, In This Our World (1893), brought her first real fame. For the next twenty years, she became well-known for her lectures. She spoke about women's issues, ethics, work, human rights, and social reform. Her lecture tours took her all over the United States. She often included these topics in her stories.

From 1894 to 1895, Gilman edited a magazine called The Impress. She wrote poems, editorials, and other articles for it. The magazine stopped printing because of social disapproval of her lifestyle. She was seen as an unconventional mother and a woman who had divorced.

In 1898, Gilman finished her book Women and Economics. This book talked about women's roles in the home. She argued for changes in how children were raised and how housework was done. She believed these changes would help women and allow them to work outside the home. The book was published the next year and made Gilman famous around the world. In 1903, she spoke at a major international meeting for women in Berlin. The next year, she toured several European countries.

In 1903, she wrote another important book, The Home: Its Work and Influence. This book expanded on her ideas from Women and Economics. She argued that women were held back in their homes and that home environments needed to change to support women's mental health.

From 1909 to 1916, Gilman wrote and edited her own magazine, The Forerunner. Many of her stories appeared in it. She wanted her magazine to "stimulate thought" and "arouse hope." The magazine had nearly 1,500 subscribers. It featured stories like "What Diantha Did" (1910), The Crux (1911), Moving the Mountain (1911), and Herland. The Forerunner is considered one of her greatest achievements. After her magazine, she wrote many articles for newspapers. Her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, was published after she died in 1935.

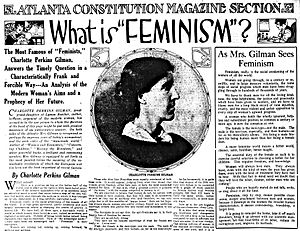

Her Ideas on Society and Women

Women's Role in Society

Gilman believed that the traditional home environment limited women. She argued that society's old beliefs about men and women held women back. She felt that men's aggressive behavior and women's roles as only mothers were not needed for survival anymore. She famously wrote, "There is no female mind. The brain is not an organ of sex."

Her main point was that women had to please their husbands to get financial support. From a young age, girls were taught to be mothers through toys and clothes. She believed there should be no difference in how boys and girls dress, what toys they play with, or what activities they do. She saw "tomboys" as ideal humans who moved freely and healthily.

Gilman argued that women's contributions to society throughout history had been stopped by a male-focused culture. She believed that women were the undeveloped half of humanity. She felt that women needed to improve to prevent society from getting worse. Gilman thought that women needed to be financially independent to truly be free and equal to men.

In Women and Economics, she argued that women were controlled by men. She also said that being a mother should not stop a woman from working outside the home. She believed that housework, cooking, and childcare should be done by professionals. Gilman wrote that the "ideal woman" was expected to be happy and cheerful while being stuck at home. She believed that when women gained financial independence, home life would improve. This is because frustration in relationships often came from wives not having enough contact with the outside world.

Gilman became a spokesperson for women's work, clothing reform, and family issues. She argued that housework should be shared equally by men and women. She also believed that young girls should be encouraged to be independent. In many of her major works, she supported women working outside the home.

Gilman thought that the idea of "home" should change. It should move from being a place where couples live together for money to a place where groups of men and women can share a "peaceful and permanent expression of personal life." She believed that everyone, not just married couples, deserved a comfortable home. She suggested building shared housing where people could live alone but still have company and comfort. This would allow both men and women to be financially independent. Marriage could then happen without anyone's money situation having to change.

Gilman also wanted to change the layout of homes. She suggested removing the kitchen from the home. This would free women from having to prepare all meals at home. The home would then truly be a personal expression of the person living in it. Ultimately, these changes would allow individuals, especially women, to become a "part of the social structure." This would be a huge change for women, who often felt limited by family life because they depended on men for money.

Feminism in Her Stories

Gilman often created worlds in her stories that showed her feminist views. Two of her stories, "What Diantha Did" and Herland, are good examples. They show that women are not just stay-at-home mothers. They are people with dreams who can travel and work like men. Their goals include a society where women are as important as men. The worlds and characters Gilman created showed the changes needed in the early 1900s, which we now call feminism.

In Herland, Gilman created a world to show the equality she wanted to see. The women of Herland are the providers. This makes them seem like the dominant sex, taking on roles usually given to men. In this society, women focus on leading the community and doing jobs usually seen as male roles. They run an entire community without the same attitudes that men often have about work. Gilman used Herland to challenge stereotypes and create a kind of paradise. She showed that qualities often seen as less valuable in women are actually strong. She used this story to show a world where women held all the power, hinting at the changes she wanted to see in her lifetime.

Gilman's feminist ideas are different in "What Diantha Did." In this story, a character named Diantha breaks away from traditional expectations for women. This shows Gilman's hopes for what women could do in real life. Diantha challenges gender norms and roles. She believes that women can solve problems in big businesses. Gilman chose for Diantha to have a career not typically for women. By doing this, she showed that the pay for traditional women's jobs was unfair. Diantha's choice to run a business allowed her to step out and join society. Gilman's works, especially "What Diantha Did," were a call for change. They were a way to reach women and encourage them to move towards freedom.

Views on Animals

Gilman's feminist writings often included ideas about how people treated domesticated animals. In Herland, her perfect society does not have any domesticated animals, including farm animals. In Moving the Mountain, Gilman talks about the problems of inbreeding in domesticated animals. In her story "When I Was a Witch," the main character helps free work horses, cats, and lapdogs. She wrote in a letter to the Saturday Evening Post that cars would stop the cruelty to horses used to pull carriages.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charlotte Perkins Gilman para niños

In Spanish: Charlotte Perkins Gilman para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |