Ludlow Massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ludlow Massacre |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Colorado Coalfield War | |||

Ruins of the Ludlow Colony in the aftermath of the massacre

|

|||

| Date | April 20, 1914 | ||

| Location |

Ludlow, Colorado, U.S.

37°20′21″N 104°35′02″W / 37.33917°N 104.58389°W |

||

| Methods | Machine guns, fire | ||

| Resulted in | Tent colony burned, Tikas and roughly 20 other residents killed. Ten days of increased fighting followed by federal military intervention. | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|

|||

| Arrests, etc | |||

|

|||

The Ludlow Massacre was a terrible event where many people were killed during the Colorado Coalfield War. It happened on April 20, 1914, in Ludlow, Colorado. Soldiers from the Colorado National Guard and private guards hired by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) attacked a camp of about 1,200 striking coal miners and their families.

Around 21 people, including miners' wives and children, died. Many people blamed John D. Rockefeller Jr., who partly owned CF&I, for the massacre. He had recently spoken to the U.S. Congress about the strikes.

This massacre was a key moment in the 1913–1914 Colorado Coalfield War. This war started because the United Mine Workers of America called a strike. Miners wanted better working conditions in CF&I's coal mines in southern Colorado. The Ludlow Massacre was the deadliest single event of the war. It led to ten days of even more violence across Colorado.

After the massacre, armed miners attacked many anti-union places. They destroyed property and fought with the Colorado National Guard. From September 1913 to April 29, 1914, when federal soldiers stepped in, about 69 to 199 people died during the strike. Historian Thomas G. Andrews called it the "deadliest strike in the history of the United States."

The Ludlow Massacre changed how people saw labor relations in America. Historian Howard Zinn called it a major event in the fight between big companies and workers. After public outrage, Congress investigated the events. Their report in 1915 helped lead to new child labor laws and the idea of an eight-hour workday.

Today, the Ludlow townsite and the camp location are a ghost town. The United Mine Workers of America owns the massacre site. They built a granite monument there to remember those who died. The Ludlow tent colony site became a National Historic Landmark in 2009.

Contents

Why the Miners Went on Strike

Areas in the Rocky Mountains have a lot of coal close to the surface. This made coal easy to get. In 1867, William Jackson Palmer noticed these coal deposits. He was planning a route for the Kansas Pacific Railway. Coal became very valuable as train travel grew quickly in the U.S.

At its busiest in 1910, Colorado's coal mining industry employed almost 16,000 people. This was 10% of all jobs in the state. A few large companies controlled Colorado's coal industry. Colorado Fuel and Iron was the biggest coal company in the West. It was one of the most powerful companies in the nation. At one point, it employed over 7,000 people.

John D. Rockefeller bought a controlling share of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company in 1902. Nine years later, he gave control to his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr.. His son managed the company from his offices in New York.

Dangers of Coal Mining

Mining was very dangerous and hard work. Miners in Colorado constantly faced dangers. These included explosions, not enough air, and collapsing mine walls. In 1912, the death rate in Colorado's mines was very high. It was 7.055 deaths for every 1,000 employees. The national rate was much lower, at 3.15.

Miners were usually paid based on how much coal they dug. But "dead work," like making sure roofs were safe, was often not paid. This system made many poor miners take risks with their lives. They would skip safety steps, which often led to deadly accidents. Between 1884 and 1912, over 1,700 miners died in Colorado accidents. In 1913 alone, 110 men died in mine-related accidents.

Life in Company Towns

Miners had few chances to complain about their problems. Many lived in company towns. In these towns, the mine owner owned all the land, houses, and services. These towns were designed to make workers loyal and stop them from complaining. Some believed that making miners' lives better would stop anger and unrest.

Company towns did bring some good things to miners' lives. They had bigger houses, better medical care, and more access to education. But owning the towns gave companies a lot of control over workers' lives. They did not always use this power for the good of the workers.

Historian Philip S. Foner said company towns were like "feudal domains." The company was like the lord and master. The "law" was just the company's rules. There were curfews. Company guards would not let any "suspicious" strangers into the camp. They also would not let any miner leave. Miners who disagreed with the company were often kicked out of their homes.

Miners Form Unions

Miners were frustrated by unsafe and unfair working conditions. They increasingly turned to unions. Across the country, organized mines had 40% fewer deaths than non-union mines. Colorado miners tried many times to form unions after the state's first strike in 1883.

Starting in 1900, the United Mine Workers of America began organizing coal miners in western states, including southern Colorado. The union decided to focus on the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. This was because of its harsh management under the Rockefellers. To stop strikes, coal companies hired strike breakers. These workers were mainly from Mexico and southern and eastern Europe. The Colorado Fuel & Iron Company mixed immigrants of different backgrounds in the mines. This was to make it harder for them to talk and organize.

The Strike Begins

Even though companies tried to stop union activity, the United Mine Workers of America secretly continued its efforts. Finally, in 1913, the union made a list of seven demands:

- The union should be recognized as the workers' voice.

- Miners should be paid for digging coal based on a 2,000-pound ton. (Before, they were paid for longer tons of 2,200 pounds).

- The eight-hour workday law should be followed.

- Miners should be paid for "dead work" (like laying tracks or supporting roofs).

- Workers should be able to choose their own weight checkmen. (This was to make sure company weightmen were honest).

- Miners should have the right to use any store, and choose their own homes and doctors.

- Colorado's laws (like mine safety rules and ending company money) should be strictly followed. The company guard system should end.

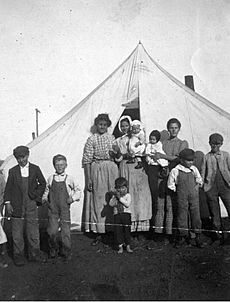

The big coal companies said no to these demands. In September 1913, the United Mine Workers of America called a strike. Miners who went on strike were kicked out of their company homes. They moved into tent villages that the union had set up. The union had leased land and built tents on wooden platforms. These tents had cast-iron stoves.

The union chose locations for the tents near canyon entrances. These canyons led to the coal camps. This was to block any strikebreakers' traffic. The company hired the Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency to protect new workers and bother the strikers.

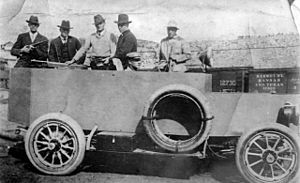

Baldwin–Felts was known for aggressive strike breaking. Their agents would shine searchlights on the tent villages at night. They also fired bullets into the tents randomly, sometimes killing or hurting people. They used an armored car with a machine gun. The union called this car the "Death Special." It was built at the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company plant.

Fights between striking miners and working miners (called "scabs" by the union) sometimes led to deaths. Frequent sniper attacks on the tent camps made miners dig pits under their tents for safety. There were also armed battles between strikers and sheriffs. These sheriffs had recently been given power to stop the strike. This was the Colorado Coalfield War.

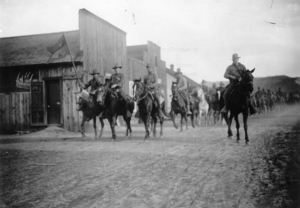

As violence grew, Colorado Governor Elias M. Ammons called in the Colorado National Guard on October 28. At first, the Guard seemed to calm things down. But the Guard leaders supported the company. Guard Adjutant-General John Chase had been involved in another violent strike years before. He set up a very strict system.

On March 10, 1914, a replacement worker's body was found near Forbes, Colorado. The National Guard said strikers had killed him. In response, General Chase ordered the Forbes tent colony destroyed. The attack happened while residents were at a funeral for two babies who had died earlier. Photographer Lou Dold saw the attack. His pictures of the destruction are often used in stories about the strike.

The strikers kept going until the spring of 1914. By then, the National Guard had mostly broken the strike. They helped mine operators bring in non-union workers. The state also ran out of money to keep the Guard there. Governor Ammons decided to call them back. But he and the mining companies feared chaos. So, they left one company of Guardsmen in southern Colorado. They formed a new group called "Troop A." This group was mostly made up of Colorado Fuel & Iron Company mine guards and Baldwin–Felts guards. They were given National Guard uniforms.

The Massacre at Ludlow

On the morning of April 20, 1914, the day after some in the tent colony celebrated Orthodox Easter, three Guardsmen came to the camp. They demanded the release of a man they said was being held against his will. The camp leader, Louis Tikas, went to meet with Major Patrick J. Hamrock at the train station. This station was about half a mile from the camp.

While they met, two groups of militia set up a machine gun on a ridge near the camp. They also took positions along a rail line. At the same time, armed Greek miners moved into a dry creek bed. Two dynamite explosions from the militia alerted the Ludlow tent colony. The miners then took positions at the bottom of the hill. When the militia started shooting, hundreds of miners and their families ran for cover.

The fighting lasted all day. More non-uniformed mine guards joined the militia later in the afternoon. As evening came, a freight train stopped on the tracks in front of the Guard's machine-gun positions. This allowed many miners and their families to escape to some hills to the east. By 7 p.m., the camp was on fire. The militia went into the camp to search and steal things.

Tikas had stayed in the camp all day. He was still there when the fire started. He and two other men were captured by the militia. Tikas and Lt. Karl Linderfelt, a Guard commander, had argued many times before. While two militiamen held Tikas, Linderfelt hit him with a rifle butt. Tikas and the other two captured miners were later found shot dead. Tikas had been shot in the back. Their bodies lay near the Colorado and Southern Railway tracks for three days. Passing trains could see them clearly. Militia officers refused to move them until a railway union member demanded they be buried.

During the battle, four women and 11 children hid in a pit under one tent. They were trapped when the tent above them caught fire. Two of the women and all the children died from smoke. These deaths became a strong reason for the United Mine Workers of America to fight. They called the event the Ludlow Massacre.

Some reports say a second machine gun was used to support the estimated 200 Guardsmen. Also, a Colorado and Southern train's operators purposely put their engine between a machine gun and the strikers. This acted as a shield against the National Guard's fire.

A board of Colorado military officers said the events started with the killing of Tikas and other strikers who were captured. They said gunfire mostly came from the southwestern part of the Ludlow Colony. Guardsmen on "Water Tank Hill" (where the machine gun was) fired into the camp. The Guardsmen said they had seen women and children leave the morning before the battle. They thought the strikers would not have started firing if women were still there. The board's official report praised the "heroic behavior" of Linderfelt and the guardsmen. They blamed the strikers for any civilian deaths, even though those killed were family members of the strikers. The report also blamed the looting that happened afterward on "Troop 'A'." This unit was mostly made up of non-uniformed mine guards who had joined the Guard.

Besides the miners and their families, three regular National Guard members and one other militiaman were reported killed. However, modern historians say only one militiaman, a private named Martin, died. Martin was shot in the neck, likely by strikers.

Aftermath of the Massacre

After the massacre, the "Ten Day War" began. This was part of the larger Colorado Coalfield War. When news of the deaths of women and children spread, union leaders called for action. They told union members to get "all the arms and ammunition legally available."

Coal miners then started a large-scale fight against mine guards and facilities across southern Colorado's coalfields. In Trinidad, the United Mine Workers of America openly gave weapons and ammunition to strikers. Over the next ten days, 700 to 1,000 strikers "attacked mine after mine." They drove off or killed guards and set buildings on fire. At least 50 people, including those at Ludlow, died during these ten days of fighting. Hundreds of state militia reinforcements were sent to the coalfields to regain control. The fighting only stopped after President Woodrow Wilson sent in federal troops. The troops took weapons from both sides. They also removed and often arrested the militia. The Colorado Coalfield War resulted in about 75 deaths in total.

The United Mine Workers of America eventually ran out of money. They called off the strike on December 10, 1914. In the end, the strikers' demands were not met. The union did not get recognized. Many striking workers were replaced. 408 strikers were arrested, and 332 were accused of murder.

Of those at Ludlow during the massacre, only John R. Lawson, a strike leader, was found guilty of murder. But the Colorado Supreme Court later overturned his conviction. Twenty-two National Guardsmen, including 10 officers, faced a court-martial. Linderfelt was found responsible for the deaths of Tikas and other strikers who had been executed. However, he and all others were found not guilty.

Reverend John O. Ferris, an Episcopalian minister, was one of the few pastors in Trinidad allowed to find and give Christian burials to the victims of the Ludlow Massacre.

Victims of the Ludlow Massacre

| Name | Also reported as | Age (years) | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardelima Costa | Fedelina/Cedilano Costa | 27 | asphyxiation, fire, or both |

| Charles Costa | Charlie Costa | 31 | shot |

| Cloriva Pedregone | Gloria/Clovine Pedregon[e] | 4 months | asphyxiation, fire, or both |

| Elvira Valdez | 3 months | asphyxiation, fire, or both | |

| Eulala Valdez | Eulalia Valdez | 8 | asphyxiation, fire, or both |

| Frank Bartolotti | Frank Bartoloti/Bartalato | Unknown | shot |

| Frank Petrucci | 6 months | asphyxiation, fire, or both | |

| Frank Rubino | 23 | shot | |

| Frank Snyder | William Snyder Jr. | 11 | shot |

| James Fyler | 43 | shot | |

| Joseph "Joe" Petrucci | 4 | asphyxiation, fire, or both | |

| Louis Tikas | Elias Anastasiou Spantidakis,

Ηλίας Αναστασίου Σπαντιδάκης, |

29 | shot |

| Lucy Costa | 4 | asphyxiation, fire, or both | |

| Lucy Petrucci | 2.5 | asphyxiation, fire, or both | |

| Mary Valdez | 7 | asphyxiation, fire, or both | |

| Onafrio Costa | Oragio Costa | 6 | asphyxiation, fire, or both |

| Patria Valdez | Patricia/Petra Valdez | 37 | asphyxiation, fire, or both |

| Primo Larese (bystander) | Presno Larce | Unknown | shot |

| Rodgerlo Pedregone | Roderlo/Rogaro Pedregon[e] | 6 | asphyxiation, fire, or both |

| Rudolph Valdez | Rodolso Valdez | 9 | asphyxiation, fire, or both |

The Legacy of Ludlow

The massacre caused anger across the country, especially against the Rockefellers. Protesters demonstrated outside the Rockefeller building in New York City. When Rockefeller Jr. went to his family estate, protesters followed him.

Even though the UMWA did not get recognized by the company, the strike had a lasting impact. It changed conditions at the Colorado mines and labor relations across the nation. John D. Rockefeller Jr. hired W. L. Mackenzie King, an expert in labor relations. King later became the Prime Minister of Canada. He helped Rockefeller develop changes for the mines and towns.

Improvements included paved roads and places for fun. Workers also got to be on committees that dealt with working conditions, safety, health, and recreation. Rockefeller Jr. said companies could not treat workers unfairly for being in unions. He also ordered the creation of a company union. The miners voted to accept Rockefeller's plan.

Rockefeller Jr. also brought in a public relations expert named Ivy Lee. Lee warned that the Rockefellers were losing public support. He created a plan for Rockefeller to fix his image. Rockefeller had to overcome his shyness. He went to Colorado to meet the miners and their families. He looked at their homes and the factories. He attended social events and listened carefully to their complaints. This was new advice and got a lot of media attention. The Rockefellers were able to solve the conflict and show a more human side of their leaders.

Over time, Ludlow became very important in how some historians saw U.S. history. Historian Howard Zinn wrote his master's thesis and several book chapters about Ludlow. George McGovern, who ran for U.S. president, also wrote his doctoral paper on the topic.

A U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations (CIR) held hearings. They gathered information and heard from everyone involved, including Rockefeller Sr. He said that even after knowing his guards had harmed strikers, he "would have taken no action" to stop them. The commission's report supported many of the changes unions wanted. It also helped bills that created a national eight-hour workday and a ban on child labor.

The last survivor of the Ludlow Massacre, Ermenia "Marie" Padilla Daley, was only 3 months old when it happened. Her father was a miner, and she was born in the camp. Her mother took her and her siblings away as the violence grew. They traveled by train to Trinidad, Colorado. The family had to split up afterward. Daley was cared for by different families and also lived in orphanages. She worked as a housekeeper and later married a consultant. His work allowed them to travel the world. Daley died on March 14, 2019, at age 105.

Ludlow in Books and Songs

Many popular songs have been written about the events at Ludlow. These include American folk singer Woody Guthrie's "Ludlow Massacre" and Red Dirt country singer Jason Boland's "Ludlow." Irish musician Andy Irvine also wrote "The Monument (Lest We Forget)."

Upton Sinclair's novel King Coal is partly based on the Ludlow Massacre. Thomas Pynchon's 2006 novel Against the Day has a chapter about the massacre.

American writer and Colorado Poet Laureate David Mason wrote a verse-novel called Ludlow (2007). It was inspired by the labor dispute. Composer Lori Laitman's opera Ludlow is based on Mason's book.

Remembering Ludlow

|

Ludlow Tent Colony Site

|

|

| Area | 40 acres (16 ha) |

|---|---|

| Built | 1913 |

| Architect | Sullivan, Hugh |

| NRHP reference No. | 85001328 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 19, 1985 |

| Designated NHL | January 16, 2009 |

The Ludlow Monument

In 1916, the United Mine Workers of America bought the land where the Ludlow tent colony was. Two years later, they built the Ludlow Monument to remember those who died. It was made from local granite. The monument was damaged in May 2003 by unknown vandals. It was repaired and unveiled again on June 5, 2005.

National Historic Landmark Site

The tent colony site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. It was named a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 2009. Even though people lived in the area after May 1914, they moved, leaving the original camp site mostly untouched. This means the site is one of the best-preserved examples of such a camp. The monument is also one of the first to remember a labor event like this. This site is the first of its kind to be studied by archeologists.

On May 7, 2003, vandals attacked the monument. They cut off the head of the male figure and the arm of the female figure. The missing parts were never found. But new ones were added in 2005 with money from donations.

Centennial Commemoration

On April 19, 2013, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper signed an order. This created the Ludlow Centennial Commemoration Commission. This group worked to create programs in the state. These included talks and exhibits to remember the Ludlow workers' struggle. They also aimed to raise awareness of the massacre. The commission worked with Colorado museums, historical societies, churches, and art galleries. They provided programs in 2014.

Studying the Past: Archaeology

In 1996, the 1913–1914 Colorado Coalfield War Project began. It was led by Randall H. McGuire, Dean Saitta, and Philip Duke. Their team later formed the Ludlow Collective. They dug up parts of the former tent colony and nearby areas to learn more about what happened.

Images for kids

-

Jesse F. Welborn, president of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company.

-

Karl Linderfelt, center. Photo caption reads: "Officers of the Colorado National Guard. From left to right: Captain R. J. Linderfelt, Lieut. T. C. Linderfelt, Lieut. K. E. Linderfelt, (who faced the charge of assault upon Louis Tikas, the dead strike leader), Lieut. G.S. Lawrence and Major Patrick Hamrock. The last three were in the Ludlow battle of April 20, 1914."

See also

In Spanish: Masacre de Ludlow para niños

In Spanish: Masacre de Ludlow para niños

- Coal Wars

- Colorado Labor Wars

- Columbine Mine Massacre of 1927

- Labor history of the United States

- Labor movement

- Labor unions

- Labor unions in the United States

- List of battles fought in Colorado

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of massacres in the United States

- List of worker deaths in United States labor disputes

- Ludlow Massacre (song)

- Mary Thomas O'Neal

- Union violence

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |