Alice Paul facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alice Paul

|

|

|---|---|

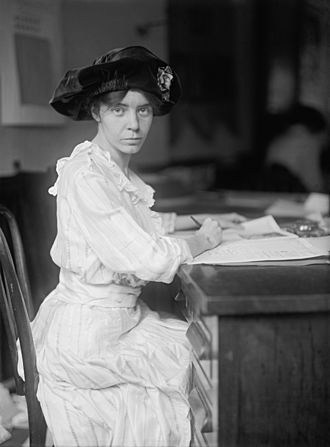

Paul in 1918

|

|

| Born |

Alice Stokes Paul

January 11, 1885 Mount Laurel, New Jersey, U.S.

|

| Died | July 9, 1977 (aged 92) Moorestown, New Jersey, U.S.

|

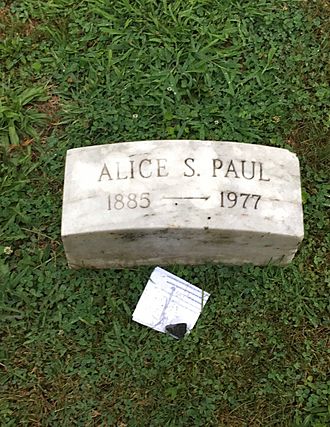

| Resting place | Westfield Friends Burial Ground, Cinnaminson, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Education | Swarthmore College (BS) Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre London School of Economics University of Pennsylvania (MA, PhD) American University (LLB, LLM, DCL) |

| Occupation | Suffragist |

| Political party | National Woman's Party |

| Parent(s) | William Mickle Paul I Tacie Parry |

Alice Stokes Paul (born January 11, 1885 – died July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker and a very important leader for women's rights. She was a key person in the fight for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This amendment made it illegal to stop someone from voting because of their gender.

Alice Paul, along with Lucy Burns and others, planned big events like the Woman Suffrage Procession and the Silent Sentinels. These actions helped women win the right to vote when the 19th Amendment passed in August 1920.

Alice Paul often faced rough treatment for her activism. But she always responded peacefully and bravely. In 1917, she was jailed in bad conditions for protesting outside the White House. She had also been jailed several times in England for fighting for women's voting rights there.

After 1920, Paul led the National Woman's Party for 50 years. This group worked for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which Alice Paul helped write. The ERA aimed to give women equal rights under the Constitution. She also helped make sure women were protected from discrimination in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Contents

Alice Paul's Early Life and School

Alice Stokes Paul was born on January 11, 1885. Her family lived at a place called Paulsdale in Mount Laurel Township, New Jersey. She was named after her grandmother, Alice Stokes. Alice had three younger brothers and sisters.

Her family were Quakers, a religious group that believes in public service. Alice learned about women's right to vote from her mother. Her mother was a member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Sometimes, Alice would go with her mother to meetings about women's suffrage.

Alice went to Moorestown Friends School and was a top student. In 1901, she went to Swarthmore College, which her grandfather helped start. While there, she was on the student government board. This experience may have sparked her interest in political action. She graduated in 1905 with a degree in biology.

After college, Alice worked at a settlement house in New York City. This work showed her the unfairness in America. But she soon realized that social work alone couldn't fix big problems. She felt that bigger changes were needed.

Alice then earned a Master of Arts degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1907. She studied political science, sociology, and economics. She continued her studies in England at the Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre.

Alice Paul's Work in England

Fighting for Women's Vote in Britain

In 1907, Alice Paul moved to England. There, she joined the British women's suffrage movement. This group was called the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She was inspired after hearing Christabel Pankhurst speak.

Alice started by selling a suffrage magazine on the streets. This was hard work and showed her how badly women activists were treated. These experiences made her believe that only equal legal rights for women could bring real change.

In London, Alice met Lucy Burns, another American activist. Lucy became a very important friend and helper in the fight for women's votes. They worked together in England and later in the United States.

Alice quickly earned the trust of the WSPU leaders. She was good at showing their message and was brave enough to put herself in danger. She and Lucy Burns helped organize events and offices for the movement.

Alice and other suffragists planned to protest a speech by a government minister. They spoke to people on the streets for a week before the event. At the meeting, Alice stood up and asked why women weren't included in the minister's ideas of progress. Police dragged her out and arrested her. This act got a lot of attention and sympathy from the public.

Later, Alice took even bigger risks. In 1909, she climbed onto a hall roof in Glasgow to speak to a crowd below. Police made her come down, but the crowd cheered her on. When she and others tried to enter the event, police beat them. Crowds gathered outside the police station, demanding their release.

In November 1909, Alice planned a protest at a fancy banquet in London. She and a friend dressed as cleaning women to get inside. When the Prime Minister began to speak, they yelled "Votes for women!" and threw a shoe. They were arrested and sentenced to a month of hard labor. Alice was sent to Holloway Prison in London.

Protests and Hunger Strikes

Alice Paul was arrested seven times and jailed three times while with the WSPU. In prison, she learned about civil disobedience from Emmeline Pankhurst. This meant demanding to be treated as a "political prisoner." This showed the public that their cause was serious. Political prisoners often got better treatment in jail.

Even though suffragettes were often denied this status, their actions got a lot of press. For example, Alice refused to wear prison clothes. When guards tried to force her, it caused a scandal and got a lot of news coverage.

Another protest method was the hunger striking. This meant refusing to eat in prison. It was effective in getting them released early and showing how badly they were treated. Alice was released early during her first two arrests because of hunger strikes. But during her third time in prison, the warden force-fed her twice a day.

Force-feeding was painful and torturous. Alice described it as terrible. After her month in prison, her health was permanently damaged. She often got sick and sometimes needed to go to the hospital. The WSPU gave Alice a special 'Hunger Strike Medal' for her bravery.

Alice Paul's Work in the United States

After her difficult time in a London prison, Alice Paul returned to the United States in 1910. She wanted to continue fighting for women's rights at home. Her experiences in England were well-known, and the American news media followed her actions.

Alice decided to focus on one main goal: getting women recognized as equal citizens. She went back to the University of Pennsylvania for her Ph.D. She also spoke to groups about her experiences in the British suffrage movement.

In 1910, Alice and Lucy Burns suggested to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) that they push for a federal amendment. This was different from NAWSA's plan to get states to allow women to vote one by one. NAWSA leaders laughed at their idea, except for Jane Addams. Alice then asked to join the organization's Congressional Committee.

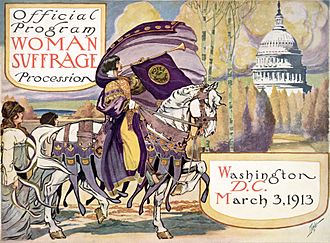

1913 Woman Suffrage Parade

One of Alice Paul's first big projects was organizing the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession. This huge parade took place in Washington, D.C., the day before President Wilson's inauguration. Alice wanted to pressure President Wilson because he had the most influence on Congress.

She got volunteers to contact suffragists across the country. In just a few weeks, Alice gathered about 8,000 marchers from most states. Alice insisted the parade go along Pennsylvania Avenue, right before President Wilson. This would show that the fight for women's votes was important and would continue.

Washington, D.C. officials didn't want the parade on that route. But Alice was determined. Congress even passed a special rule to make sure the parade could happen safely.

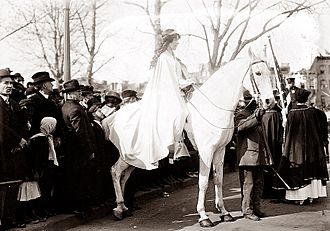

On March 3, 1913, the parade went along Alice's chosen route. It was led by lawyer Inez Milholland, who rode a horse and wore white. The New York Times called it "one of the most impressively beautiful spectacles ever staged." The parade included bands, banners, and floats. The main banner said, "We Demand an Amendment to the United States Constitution Enfranchising the Women of the Country."

Some groups wanted black and white women to march separately. After much talk, NAWSA decided black women could march where they wished. But Ida B. Wells was asked not to march with the Illinois group. She ended up joining the Chicago group and marched with them.

Over half a million people came to watch the parade. But there wasn't enough police protection. The crowd pressed in so much that the women couldn't move. Police did little to help. Eventually, the National Guard and college students stepped in to protect the marchers. Some Boy Scouts even gave first aid to those hurt. This event made many people more aware of and sympathetic to the suffrage cause.

After the parade, NAWSA focused on getting a constitutional amendment for women's voting rights. This idea had been started by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton years before.

National Woman's Party

Alice Paul's strong methods caused some disagreement with NAWSA leaders. They felt she was moving too fast. Because of these differences, Alice left NAWSA. She then formed the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. Later, in 1916, she created the National Woman's Party (NWP).

The NWP used some of the protest methods from Britain. They focused only on getting a constitutional amendment for women's suffrage. Alva Belmont, a very rich socialite, was a big supporter of Alice's efforts. The NWP also published a weekly newspaper called The Suffragist.

Silent Sentinels

In 1916, Alice Paul and the NWP campaigned against President Woodrow Wilson. He and other Democrats refused to support the Suffrage Amendment. In January 1917, the NWP started the first political protest outside the White House.

These protesters were called the "Silent Sentinels". They dressed in white and stood silently, holding banners demanding the right to vote. Over two years, 2,000 women took part, protesting six days a week. Alice knew that showing the President's attitude toward suffrage was key.

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, many people thought the Silent Sentinels were disloyal. But Alice Paul made sure the protests continued. In June 1917, protesters were arrested for "obstructing traffic." Over the next six months, many, including Alice, were jailed.

When the public heard about the arrests, they were surprised. Important women were going to prison for peaceful protest. President Wilson got bad publicity. He quickly pardoned the first women arrested. But news of the arrests and mistreatment continued.

Suffragists kept picketing the White House during World War I. Their banners asked, "Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait For Liberty?" They also used Wilson's own quotes to make their point. Even though they protested peacefully, they were sometimes attacked. Young men would harass and beat the women. Police often did not help the protesters and sometimes arrested men who tried to help them. More protesters were arrested and jailed.

Prison, Hunger Strikes, and the 19th Amendment

Alice Paul purposely got a seven-month jail sentence starting in October 1917. She wanted to show support for other activists. She was sent to the District Jail.

The women in jail were not treated as political prisoners. They lived in harsh conditions with poor hygiene and bad food. To protest these conditions, Alice Paul started a hunger strike. Because of this, she was moved to the prison's mental ward. There, she was force-fed raw eggs through a tube. Alice later said it was "shocking that a government of men could look with such extreme contempt on a movement that was asking nothing except such a simple little thing as the right to vote."

On November 14, 1917, the suffragists at Occoquan Workhouse faced brutal treatment. This event became known as the "Night of Terror". The National Woman's Party went to court to protest this treatment. Despite the harshness she faced, Alice Paul remained strong. On November 27 and 28, all the suffragists were released from prison. Within two months, President Wilson announced his support for a bill on women's right to vote.

After Women Gained the Vote

After women won the right to vote in 1920, the National Woman's Party (NWP) kept working for women's legal equality. Alice Paul and NWP members helped include equality for women in the United Nations charter. The NWP is credited with helping to write over 300 laws. Alice Paul remained a leader until she moved to Connecticut in 1974.

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

Once women could vote, Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party focused on the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman wrote the ERA. It was first presented to Congress in 1923. The original text said, "Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States."

In 1943, the amendment was renamed the "Alice Paul Amendment." Its wording changed to what it is today: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex." For Alice Paul, the ERA was important because it was a constitutional amendment. She believed it could unite women around a common goal.

Not everyone agreed about the ERA. Some of Alice's allies worried it would remove laws that protected women in the workplace. These laws set limits on working hours or conditions for women. Opponents argued that if the ERA guaranteed equality, these protective laws would disappear. The League of Women Voters (LWV) opposed the ERA for this reason.

But Alice Paul and the NWP believed that sex-based workplace laws actually hurt women. They felt these laws stopped women from getting good jobs and earning fair wages. Alice believed that women should be treated equally under the law, not as a group that needed special protection. She called such protections "legalized inequality." For Alice, the ERA was the best way to ensure legal equality for all women.

Alice Paul continued to work with the NWP. She also pushed for similar efforts in state laws and international agreements. She helped make sure the United Nations included equality for women in its statements. She hoped this would encourage the United States to do the same.

She also worked to change laws that affected a woman's citizenship if she married a foreign man. Before, American women who married foreign men could lose their U.S. citizenship. Alice saw this as unfair. She worked for the international Equal Nationality Treaty in 1933. In the U.S., she helped pass the Equal Nationality Act in 1934. This law allowed women to keep their citizenship after marriage.

The ERA was introduced in Congress in 1923. It gained and lost support over the years. In the late 1930s, more women worked in jobs usually held by men during the war. This increased public support for the ERA. In 1946, the ERA passed the Senate but not by enough votes to move forward. Four years later, it passed the Senate again but failed in the House.

Alice Paul was happy when the women's movement grew in the 1960s and 1970s. She hoped this would lead to the ERA's victory. When the bill finally passed Congress in 1972, Alice was unhappy about new changes. It now included a time limit for states to approve it. Alice correctly predicted that this time limit would cause its defeat. The ERA did get a three-year extension, but it still fell short of the states needed for approval.

States continued to try and approve the ERA even after the deadline. In 2017 and 2019, resolutions were introduced in Congress to remove the deadline. If these pass, some experts believe the amendment could become law.

1964 Civil Rights Act

Alice Paul played a big part in adding protection for women to the Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This was done despite some opposition. Howard W. Smith, a powerful politician, added the rule against sex discrimination to the Civil Rights Act.

Smith had supported the Equal Rights Amendment for 20 years because he believed in equal rights for women. Alice Paul and other feminists had worked with Smith since 1945. They wanted to find a way to include sex as a protected group in civil rights laws.

Alice Paul's Personal Life and Death

Alice Paul had an active social life until she moved to Washington, D.C., in 1912. She had close friendships with women and sometimes dated men. She didn't keep many personal letters, so we don't know much about her private life. Once she focused on winning the vote for women, that became her main priority.

However, Elsie Hill and Dora Kelly Lewis, two women she met early in her work, remained close friends throughout her life. She also knew William Parker, a scholar, for several years. He may have asked her to marry him in 1917.

Alice Paul became a vegetarian around the time of the suffrage campaign.

In 1974, Alice Paul had a stroke. She was placed in a nursing home. News of her financial struggles reached friends, and a fund for Quakers quickly helped her. Alice Paul died at age 92 on July 9, 1977. She passed away at a Quaker facility in Moorestown, New Jersey, close to where she was born. She is buried at Westfield Friends Burial Ground in Cinnaminson, New Jersey. People often leave notes at her tombstone to thank her for her work for women's rights.

Alice Paul's Legacy

Alice Paul was honored in the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1979. In 2010, she was also added to the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

Her college, Swarthmore College, named a dormitory Alice Paul Residence Hall after her. Montclair State University in New Jersey also has an Alice Paul Hall. In 2016, President Barack Obama named the Sewall-Belmont House the Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument. It was named for Alice Paul and Alva Belmont. The University of Pennsylvania has the Alice Paul Center for Research on Gender, ***, and Women.

Two countries have honored her with postage stamps: Great Britain in 1981 and the United States in 1995.

Alice Paul appeared on a United States gold coin in 2012. In 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department announced that her image would be on the back of a new $10 bill. She will be shown with other important women like Lucretia Mott and Susan B. Anthony. The new designs for U.S. bills will be shown in 2020. This will be for the 100th anniversary of American women winning the right to vote.

In 1987, a group of New Jersey women bought Alice Paul's papers at an auction. They wanted to create an archive of her work. Her papers are now kept at Harvard University and the Smithsonian Institution. In 1990, the same group, now called the Alice Paul Institute, bought her childhood home, Paulsdale. Paulsdale is a National Historic Landmark. The Alice Paul Institute shares her story and promotes gender equality.

Hilary Swank played Alice Paul in the 2004 movie Iron Jawed Angels. This film showed the women's suffrage movement in the 1910s. In 2018, Alice Paul was a main character in an episode of the TV show Timeless. On January 11, 2016, Google Doodle honored her 131st birthday.

See also

In Spanish: Alice Paul para niños

In Spanish: Alice Paul para niños

- Iron Jawed Angels, a 2004 film about Alice Paul and Lucy Burns and their work for the 19th Amendment.

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

- Women's suffrage organizations

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |