Mellitus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mellitus |

|

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

| Appointed | 619 |

| Reign ended | 24 April 624 |

| Predecessor | Laurence |

| Successor | Justus |

| Other posts | Bishop of London |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 604 by Augustine |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 24 April 624 Canterbury |

| Buried | St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 24 April |

| Venerated in | |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

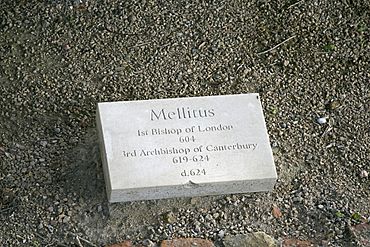

Mellitus (died 24 April 624) was an important early Christian leader in England. He was the first bishop of London during the Saxon period and later became the third Archbishop of Canterbury. Mellitus was part of the Gregorian mission, a group sent by Pope Gregory I to England. Their goal was to help the Anglo-Saxons change from their traditional beliefs to Christianity.

Mellitus arrived in England in 601 AD with more clergy to help the mission. In 604, he was made the Bishop of London. Pope Gregory I sent him a famous letter, the Epistola ad Mellitum, which suggested converting the Anglo-Saxons slowly. This letter said they could mix some pagan customs with Christian ones. In 610, Mellitus traveled to Italy for a meeting of bishops. He returned to England with letters from the Pope for the missionaries.

After King Sæberht of Essex died around 616, his pagan sons forced Mellitus to leave London. King Æthelberht of Kent, another supporter of Mellitus, also died around this time. Mellitus had to find safety in Gaul (modern-day France). He came back to England the next year after Æthelberht's successor became Christian. However, Mellitus could not return to London because its people were still pagan. In 619, Mellitus became the Archbishop of Canterbury. People believed he miraculously saved the cathedral and much of Canterbury from a fire. After he died in 624, Mellitus was honored as a saint.

Mellitus's Early Life

The old writer Bede said that Mellitus came from a noble family. In his letters, Pope Gregory I called Mellitus an abbot. It is not clear if Mellitus was already an abbot of a monastery in Rome. Or if this title was given to him to make his journey to England easier. This would have made him the leader of the group.

The Pope's records describe him as an "abbot in Frankia." But the letter itself just says "abbot." The first time Mellitus is mentioned in history is in Gregory's letters. We don't know anything else about his background. It seems likely he was from Italy, just like all the other bishops that Augustine had made.

Journey to England

Pope Gregory I sent Mellitus to England in June 601. This was because Augustine, the first Archbishop of Canterbury, had asked for more help. Augustine needed more clergy to join the mission that was converting the kingdom of Kent. King Æthelberht ruled Kent at that time.

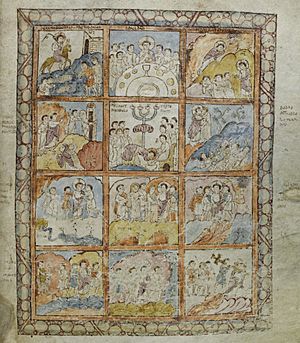

The new missionaries brought gifts like books and "all things which were needed for worship." A writer from the 1400s, Thomas of Elmham, said that some of the books Mellitus brought were still in Canterbury in his day. Experts have looked at the remaining old books. They think that one book that might have survived is the St Augustine Gospels. This book is now in Cambridge.

Along with a letter for Augustine, the missionaries brought a letter for King Æthelberht. This letter urged the King to be like the Roman Emperor Constantine I. It encouraged him to make his people become Christians. The king was also told to destroy all pagan shrines.

While Mellitus was traveling to England, he received another letter from Pope Gregory. This letter allowed Augustine to change pagan temples into Christian churches. It also allowed them to turn pagan animal sacrifices into Christian feasts. This was to make the change to Christianity easier for people. This letter was a big change in how the mission worked. It was later included in Bede's book Ecclesiastical History of the English People. This letter is usually called the Epistola ad Mellitum.

Bishop of London

We don't know exactly when Mellitus and his group arrived in England. But he was definitely there by 604. That year, Augustine made him a bishop in the area of the East Saxons. This made Mellitus the first Bishop of London after the Romans left. London was the capital of the East Saxons.

London was a good choice for a new bishopric (an area led by a bishop). It was a main city for the southern roads. It was also an old Roman town. Many of the mission's efforts focused on such places. Before he became bishop, Mellitus baptized Sæberht, King Æthelberht's nephew. Sæberht then allowed the bishopric to be set up. King Æthelberht probably built the church in London, not Sæberht. Bede wrote that Æthelberht gave land to support the new bishopric. However, a document that claims to be a land grant from Æthelberht to Mellitus is a later fake.

Pope Gregory had wanted London to be the main archbishopric for the southern part of the island. But Augustine never moved his main church to London. Instead, he made Mellitus a regular bishop there. After Augustine died in 604, Canterbury remained the site of the southern archbishopric. London stayed a bishopric. Maybe the King of Kent did not want a higher church authority outside his own kingdom.

Mellitus went to a meeting of bishops in Italy in February 610. Pope Boniface IV called this meeting. One reason Mellitus might have gone was to show that the English Church was independent from the Frankish Church. Boniface had Mellitus take two letters back to England. One was for Æthelbert and his people. The other was for Laurence, the Archbishop of Canterbury. He also brought back the decisions from the meeting.

During his time as a bishop, Mellitus joined Justus, the Bishop of Rochester. They signed a letter that Laurence wrote to the Celtic bishops. This letter urged the Celtic Church to use the Roman way of figuring out the date of Easter. This letter also said that Irish missionary bishops, like Dagan, would not eat with the Roman missionaries.

Both King Æthelberht and King Sæberht died around 616 or 618. This caused big problems for the mission. Sæberht's three sons had not become Christian. They drove Mellitus out of London. Bede says that Mellitus was exiled because he would not give the brothers some of the sacramental bread.

Mellitus first ran to Canterbury. But Æthelberht's new king, Eadbald, was also pagan. So Mellitus, with Justus, found safety in Gaul. Laurence, the second Archbishop of Canterbury, called Mellitus back to Britain. This happened after Laurence converted King Eadbald to Christianity. We don't know how long Mellitus was exiled. Bede says it was a year, but it might have been longer. Mellitus did not go back to London because the East Saxons were still pagan. The bishopric in London was not filled again until Cedd became bishop around 654.

Archbishop and Death

Mellitus became the third Archbishop of Canterbury after Laurence died in 619. During his time as archbishop, Mellitus was said to have done a miracle in 623. A fire started in Canterbury and threatened the church. Mellitus was carried into the flames. Then, the wind changed direction, saving the building. Bede praised Mellitus's good sense. But other than this miracle, not much else happened during his time as archbishop. Bede also said that Mellitus suffered from gout. Pope Boniface wrote to Mellitus, encouraging him in his mission. This might have been because of the marriage of Æthelburh of Kent to King Edwin of Northumbria. We don't know if Mellitus received a pallium, which is a symbol of an archbishop's power, from the pope.

Mellitus died on 24 April 624. He was buried at St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury on the same day. After his death, he was honored as a saint. His feast day is 24 April. In the 800s, Mellitus's feast day was mentioned in a prayer book called the Stowe Missal. He was still honored at St Augustine's in 1120, along with other local saints. There was also a special place for him at Old St Paul's Cathedral in London.

After the Norman Conquest, a writer named Goscelin wrote about Mellitus's life. This was the first of several such writings around that time. But none of them had new information not already in Bede's earlier works. However, these later writings show that during Goscelin's time, people with gout were told to pray at Mellitus's tomb. Goscelin wrote that Mellitus's shrine was next to Augustine's and Laurence's in the eastern part of the church.

See also

In Spanish: Melito de Canterbury para niños

In Spanish: Melito de Canterbury para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |