Eadbald of Kent facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Eadbald |

|

|---|---|

Coin of Eadbald of Kent

|

|

| King of Kent | |

| Reign | 24 February 616 – 20 January 640 |

| Predecessor | Æthelberht |

| Successor | Eorcenberht |

| Died | 20 January 640 |

| Spouse | Emma of Austrasia |

| Issue | Eormenred Eorcenberht Eanswith |

| Father | Æthelberht |

| Mother | Bertha |

Eadbald (Old English: Eadbald) was the King of Kent from 616 until he died in 640. He was the son of King Æthelberht and his wife Bertha. His father, Æthelberht, made Kent a very strong kingdom in England. Æthelberht was also the first Anglo-Saxon king to become a Christian after following Anglo-Saxon paganism.

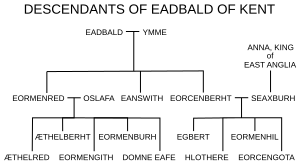

When Eadbald became king, it was a difficult time for the Christian church. He followed the old pagan religion and did not become Christian for a while. Later, he was converted by either Laurentius or Justus. The church also asked him to separate from his first wife, who had been his stepmother. Eadbald's second wife was Emma, who might have been a Frankish princess. They had two sons, Eormenred and Eorcenberht, and a daughter, Eanswith.

Eadbald was not as powerful as his father, but Kent was still strong. It was not controlled by Edwin of Northumbria, a powerful king from the north. Edwin married Eadbald's sister, Æthelburg. This created a good friendship between Kent and Northumbria. When Edwin died around 633, Æthelburg went back to Kent. She sent her children to Francia (modern-day France) to keep them safe. The royal family of Kent made many important marriages. For example, Eadbald's niece, Eanflæd, married Oswiu, and his son Eorcenberht married Seaxburh.

Eadbald died in 640. He was buried in the Church of St Mary in Canterbury, which he had built. His son Eorcenberht became the next king. Eormenred, Eadbald's other son, might have been an older son. If he ruled at all, it was only as a junior king alongside Eorcenberht.

Contents

Kent's Beginnings and Key Historical Records

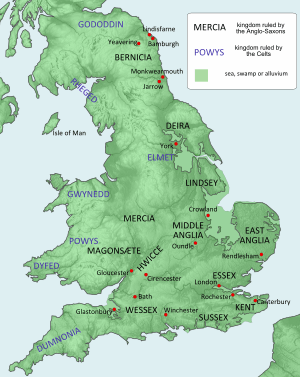

People from continental Europe, mainly the Jutes, settled in Kent by the end of the 500s. Eadbald's father, Æthelberht, likely became king around 589 or 590. It's hard to know the exact dates of his rule. An early writer named Bede said that Æthelberht had great power, called imperium, over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. This power brought wealth to Kent. Kent was a strong kingdom when Æthelberht died in 616. It had good trade connections with Europe.

Before the Anglo-Saxons, Roman Britain was Christian. But the Anglo-Saxons followed their own native religion. In 597, Augustine was sent by Pope Gregory I to England. His mission was to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Augustine landed in eastern Kent and soon converted King Æthelberht. Æthelberht gave Augustine land in Canterbury. Two other kings, Sæberht of Essex and Rædwald of East Anglia, also became Christian because of Æthelberht's influence.

An important book for learning about this time is The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. It was written in 731 by Bede, a Benedictine monk from Northumbria. Bede was most interested in how England became Christian. But he also wrote a lot about the history of the kings, including Æthelberht and Eadbald. Bede got some of his information from Albinus, who was the head of a monastery in Canterbury. Other texts, called the Legend of St Mildrith, also give details about Eadbald's children. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of historical records, also helps us understand this period. We also learn from letters from the Pope, lists of Kentish kings, and old documents called charters. Charters were used to record land given by kings to their followers or the church. No original charters from Eadbald's time still exist, but some later copies do.

Eadbald's Family and Ancestry

Bede wrote about the family of Æthelberht, Eadbald's father. He said Æthelberht came from a legendary founder of Kent, Hengist. However, many historians think Hengist and his brother Horsa were probably made-up characters. We know that Æthelberht married twice. Eadbald married his stepmother after his father died, which the church did not approve of.

Eadbald had a sister named Æthelburg. She was likely also Bertha's child. Æthelburg married Edwin, who was a very powerful Anglo-Saxon king. There might have been another brother named Æthelwald. A letter from the Pope to Justus, the archbishop of Canterbury, mentions a king named Aduluald. This king seems to be different from Eadbald. Scholars are not sure what this means. "Aduluald" might be "Æthelwald," suggesting another king, perhaps a ruler of west Kent. Or it might just be a mistake in the writing.

Archbishop Laurence of Canterbury convinced Eadbald to become Christian and leave his first wife. Eadbald then married his second wife, Ymme. Kentish stories say she was from the Frankish royal family. Some recent ideas suggest she might have been the daughter of Erchinoald, a powerful official in Francia.

East and West Kent Kingdoms

The lists of kings show that only one king ruled Kent at a time. However, it was common for Anglo-Saxons to have smaller kingdoms within a larger one. From the late 600s, during the rule of Hlothhere, Kent often had two kings. One king was usually more powerful. It's not as clear if this was true before Hlothhere. Some old documents, which are now known to be fake, suggest Eadbald ruled west Kent as a junior king while his father was alive. The Pope's letter that might mention Eadbald's brother, Æthelwald, calls him a king. If he existed, he would have been a junior king under Eadbald.

Kent was divided into east and west parts. West Kent has fewer old objects found by archaeologists than east Kent. The objects found in east Kent look different and show influences from the Jutes and Franks. This archaeological evidence, along with the idea of two kingdoms, suggests that the eastern part conquered the western part. The eastern part was likely settled first by the invaders.

Eadbald Becomes King and the Return to Paganism

|

|

| Front: Bust of Eadbald right. AVDV[ARLD REGES] | Back: Cross on globe within wreath. ++IÞNNBALLOIENVZI |

| Gold thrymsa coin of Eadbald of Kent, London (?), 616–40 | |

Eadbald became king when his father died on February 24, 616, or possibly 618. Even though his father Æthelberht and his mother Bertha were Christian, Eadbald was a pagan. Bertha died before Eadbald became king, and Æthelberht married again. We don't know the name of Æthelberht's second wife. But she was likely pagan because she married Eadbald, her stepson, after Æthelberht's death. The church did not allow a marriage between a stepmother and stepson.

Bede wrote that Eadbald turning away from Christianity was a "severe setback" for the church. Sæberht, the king of Essex, had become Christian because of Æthelberht. But when Sæberht died around the same time, his sons forced Mellitus, the bishop of London, to leave. Bede said Eadbald was punished for his lack of faith by "frequent fits of insanity" and being controlled by an "evil spirit." This might have meant he had epileptic fits or another illness. But he was eventually convinced to give up paganism and his first wife.

Eadbald's second wife, Ymme, was a Frank. Kent had strong connections with Francia, which might have helped Eadbald convert. The missionaries in Canterbury seemed to have support from the Franks. In the 620s, Eadbald's sister Æthelburg came to Kent. She sent her children to the court of King Dagobert I in Francia for safety. Besides family ties, trade with the Franks was very important for Kent. It is thought that Frankish pressure helped convince Æthelberht to become Christian. Eadbald's conversion and marriage to Ymme were likely connected to these important diplomatic decisions.

Two graves from an old Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Finglesham show objects from this time. They include a bronze pendant and a gold buckle. Their designs are similar and might be symbols of religious activities involving the Germanic god Woden. These objects probably date from the time when people returned to paganism.

Bede's Story of Conversion

Bede's story about Eadbald rejecting the church and then converting is quite detailed. Here is Bede's version of events:

- February 24, 616: Æthelberht dies, and Eadbald becomes king.

- 616: Eadbald leads a return to paganism. He marries his stepmother, which the church forbids. He refuses to be baptized. Around this time, Mellitus, bishop of London, is forced out by Sæberht's sons and goes to Kent.

- 616: Mellitus and Justus, bishop of Rochester, leave Kent for Francia.

- 616/617: After Mellitus and Justus leave, Laurence, the archbishop of Canterbury, plans to leave too. But he has a vision where St Peter whips him. In the morning, he shows the scars to Eadbald. Eadbald then becomes Christian.

- 617: Justus and Mellitus return from Francia "the year after they left." Justus goes back to Rochester.

- Around 619: Laurence dies, and Mellitus becomes archbishop of Canterbury.

- 619–624: Eadbald builds a church, and Archbishop Mellitus dedicates it.

- April 24, 624: Mellitus dies, and Justus becomes archbishop of Canterbury.

- 624: After Justus becomes archbishop, Pope Boniface writes to him. The Pope says he heard from King Aduluald (possibly Eadbald) that the king converted to Christianity. Boniface sends a special cloth called a pallium with this letter.

- By 625: Edwin of Deira, king of Northumbria, asks to marry Æthelburg, Eadbald's sister. Edwin is told she must be allowed to practice Christianity. He also has to think about becoming Christian himself.

- July 21, 625: Justus makes Paulinus a bishop in York.

- July or later in 625: Edwin agrees to the marriage terms. Æthelburg travels to Northumbria with Paulinus.

- Easter 626: Æthelburg gives birth to a daughter, Eanflæd.

- 626: Edwin finishes a war against the West Saxons. Around this time, Pope Boniface writes to both Edwin and Æthelburg. The letter to Edwin encourages him to become Christian and mentions Eadbald's conversion. The letter to Æthelburg says the Pope recently heard about Eadbald's conversion. It encourages her to help her husband Edwin convert.

Kent's Connections with Other Kingdoms

Eadbald's power over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was less than his father Æthelberht's. Eadbald could not help Mellitus return to London. Bede said Eadbald's power in Essex "was not so effective as that of his father." However, Kent was still strong enough that other kingdoms wanted to be allies with Eadbald's family. Edwin's marriage to Eadbald's sister, Æthelburg, probably helped him get better access to trade with Europe. This alliance was also good for Eadbald. It might be why Edwin's power over Britain did not include Kent.

Another reason Edwin treated Kent well might be because Canterbury was where the archbishop lived. Edwin knew how important Canterbury's church status was. He even planned to make York an archbishopric too, with Paulinus as the first archbishop. Paulinus later returned to Kent. At Eadbald's and Archbishop Honorius's request, he became bishop of Rochester. York did not become an archbishopric for another hundred years.

Within a year of Edwin's death in 633 or 634, Oswald became king of Northumbria. It seems his relationship with Eadbald was similar to Edwin's. Oswald's successor, Oswiu, married Eanflæd. She was Edwin's daughter and Eadbald's niece. This marriage gave Oswiu connections to both Deira and Kent.

Eadbald and Ymme had a daughter, Eanswith. She started the first nunnery in England at Folkestone, near Canterbury. They also had two sons, Eorcenberht and Eormenred. Eormenred was the older son. He might have been a junior king of Kent. He seems to have died before his father, so Eorcenberht became king. An extra son, Ecgfrith, is mentioned in a document from Eadbald's time. But this document is a fake, probably from the 1000s.

Many of Eadbald's close relatives married into other royal families. King Anna of East Anglia's daughter, Seaxburh, married Eorcenberht. Their daughter Eormenhild married Wulfhere of Mercia, a very powerful king. Eanflæd, Eadbald's niece, married Oswiu. He was king of Northumbria and the last northern Angle king Bede said had imperium over southern England. Eadbald's granddaughter Eafe married Merewalh, king of the Magonsæte.

Trade and Connections with the Franks

We don't have many written records about trade during Eadbald's rule. We know that the kings of Kent controlled trade by the late 600s. But we don't know how early this control started. Archaeological finds suggest that royal influence over trade began even before written records. It might have been Eadbald's father, Æthelberht, who took control of trade from the nobles and made it a royal business. Trade with Europe brought luxury goods to Kent. This was an advantage when trading with other Anglo-Saxon nations. The money from trade was also very important. Kent traded local glass and jewelry with the Franks. Kentish goods have been found as far south as the mouth of the Loire in France. There was probably also a busy slave trade. The wealth from this trade might be why Kent remained important, even if its power was less than before.

Coins were probably first made in Kent during Æthelberht's rule, but none have his name on them. These early gold coins were likely the shillings (Old English: scillingas) mentioned in Æthelberht's laws. Coin experts also call these coins "thrymsas." Thrymsas from Eadbald's rule are known, but few have his name. One such coin was made in London and says "AVDVARLD." Some think that kings did not have complete control over making coins at that time.

Connections with Francia were more than just trade and royal marriages. Eadbald's granddaughter, Eorcengota, became a nun at Faremoutiers. His great-granddaughter, Mildrith, was a nun at Chelles. When Edwin was killed around 632, Æthelburg, with Paulinus, sailed to Eadbald's court in Kent. But to keep her children safe from Eadbald and Oswald of Northumbria, she sent them to the court of King Dagobert I of the Franks. This shows how strong her family's ties were across the English Channel.

Succession to the Throne

Eadbald died in 640. Most stories in the Kentish Royal Legend say his son Eorcenberht became king alone. However, an old text calls Eormenred "king." This might mean he was a junior king under Eorcenberht, or that they shared the kingship. One idea is that the other version of the story, which doesn't give him a title, might have been an attempt to make royal claims from Eormenred's family seem less important.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |