Anglo-Saxon paganism facts for kids

Anglo-Saxon paganism was the main religion of the Anglo-Saxons in England from the 5th to the 8th centuries AD. It was a type of Germanic paganism found across northern Europe. This religion had many different beliefs and practices, which varied from region to region.

It came to Britain with the Anglo-Saxon people in the mid-5th century. It was the main religion until the Anglo-Saxons became Christian between the 7th and 8th centuries. Some parts of it later mixed into English folklore. The words "paganism" and "heathenism" were first used by Christians to describe this religion. The Anglo-Saxons themselves didn't have a name for their own beliefs.

We learn about Anglo-Saxon paganism from three main sources:

- Written texts by Christian Anglo-Saxons like Bede.

- Place names (names of towns or areas).

- Archaeological finds, like burial sites.

We can also learn about it by comparing it to the pre-Christian beliefs of nearby groups, like the Norse.

Anglo-Saxon paganism was a religion with many gods, called ése (singular ós). The most important god was probably Woden. Other important gods included Thunor and Tiw. People also believed in other magical creatures living in the land, such as elves, nicors, and dragons.

Religious practices often involved showing respect to these gods. This included offering things like objects and animals, especially during special festivals throughout the year. There is some proof of wooden temples, but other holy places might have been outdoors. These could have included special trees and large stones.

We don't know much about what pagans believed about life after death. However, these beliefs likely shaped their burial practices. The dead were either buried or cremated, usually with special items called grave goods. This religion also likely included ideas about magic and witchcraft. Some parts of it might even be called a form of shamanism.

The names of the days of the week in English come from these gods. What we know about this religion and its stories has also influenced literature and Modern Paganism.

Contents

Understanding Anglo-Saxon Paganism

The word pagan comes from Latin. Christians in Anglo-Saxon England used it for people who were not Christian. In Old English, the word was hæðen ("heathen"). Both "pagan" and "heathen" were often used in a negative way. Hæðen was also used for criminals in later Anglo-Saxon writings.

There is no proof that Anglo-Saxons called themselves "pagans." They didn't see their beliefs as one single religion that was different from Christianity. Their beliefs were a part of their daily lives. Experts like Martin Carver say Anglo-Saxon paganism was "not a religion with rules for everyone." Instead, it was a mix of local ideas about the world.

Historian Marilyn Dunn called Anglo-Saxon paganism a "world accepting" religion. This means it focused on life here and now. It cared about family safety, wealth, and avoiding problems like drought or hunger. She also called it a "folk religion." This means followers focused on surviving and doing well in this world.

Using terms like "paganism" or "heathenism" can be tricky. Early scholars used them for beliefs before Christianity in the 7th century. But some experts now say using "pagan" makes us see things from the Christian missionaries' point of view. This can hide what the Anglo-Saxons themselves believed.

Today, some scholars avoid "paganism." Others still use it because it helps describe non-Christian religious beliefs. "Traditional religion" or "pre-Christian religion" are other terms used. However, "traditional" might not be right because Anglo-Saxon England was full of new ideas. "Pre-Christian" is better, but not always correct for timing.

How We Know About This Religion

The Anglo-Saxons before Christianity did not write things down. So, we don't have their own written records. Our main written information comes from later Christian writers. These include Bede and the author of the Life of St Wilfrid. They wrote in Latin, not Old English. These writers were not trying to fully describe pagan beliefs. So, our written information is incomplete.

Writings from Christian Anglo-Saxon missionaries are also helpful. These missionaries worked to convert pagan groups in Europe. The Roman writer Tacitus also wrote about the pagan religions of the Anglo-Saxons' ancestors. Historian Frank Stenton said the texts give us only "a dim impression" of pagan religion.

There are fewer written records about Anglo-Saxon paganism than for nearby places like Ireland or Scandinavia. There is no clear, formal book of Anglo-Saxon pagan beliefs. Many scholars use Norse mythology to understand Anglo-Saxon beliefs. But some warn against this, as the two might have been different.

Old English place names also give us clues about pre-Christian beliefs. Some names refer to gods, while others describe religious practices. These names are mostly in central and south-east England. It's not clear why they are rare in other areas. This might be due to later Scandinavian settlers or Christian efforts. In 1941, Frank Stenton found about 50 to 60 possible pagan worship sites from place names.

Archaeological finds are very useful for studying paganism. Archaeologist David Wilson says they are "prolific." We can only find religion, ritual, and magic in archaeology if they left physical traces. So, our understanding relies on rich burials and large buildings. Metal objects found by metal detectorists also help. It's hard for scholars to separate religious activities from daily life. Much of the archaeological material comes from when Christianity was replacing paganism.

Expert Audrey Meaney said there is "very little undoubted evidence for Anglo-Saxon paganism." She noted we still don't know many important details.

How the Religion Changed Over Time

Coming to Britain and Becoming Established

For most of the 4th century, Britain was part of the Roman Empire. Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380 AD. But in Britain, Christianity was likely a minority religion. It was mostly in cities. In the countryside, older polytheistic beliefs probably continued.

Britons living in Anglo-Saxon areas might have adopted the Anglo-Saxons' pagan religion. This could have helped them get ahead. It was easier for Britons who already practiced polytheistic beliefs. Their old beliefs might have mixed with the new Anglo-Saxon religion.

Some small signs suggest Roman Christianity survived a little. For example, place names like ecclēs (meaning 'church') are found in Norfolk and Kent. But historian John Blair thinks Roman Christianity had only a "ghost-life" in Anglo-Saxon areas. British Christians were likely seen as lower class. They probably didn't influence the pagan kings much.

Earlier scholars thought Anglo-Saxon paganism came from an older "Germanic paganism." But Michael Bintley warns that this "Germanic paganism" was never one single thing.

The Shift to Christianity

Anglo-Saxon paganism lasted for a relatively short time, from the 5th to the 8th centuries. We learn about the shift to Christianity from Christian writings. In 596, Pope Gregory I sent a mission to convert the Anglo-Saxons. Augustine, the mission leader, arrived in Kent in 597.

Christianity first spread in Kent. Then, it grew a lot between 625 and 642. Kings like Eadbald and Oswald supported Christian missions. The next phase was from about 653 to 664. During this time, rulers of other kingdoms became Christian. Finally, in the 670s and 680s, the last two pagan Anglo-Saxon kingdoms became Christian.

Like in other parts of Europe, the change to Christianity was helped by the ruling class. These rulers might have felt behind compared to Christian kingdoms in Europe. The speed of conversion varied. Most Anglo-Saxon kingdoms went back to paganism for a short time after their first Christian king died. But by the late 680s, all Anglo-Saxon peoples were at least officially Christian.

It's hard to know how popular old beliefs stayed among common people. Laws from 695 punished those who offered things to "demons." But later, Bede wrote as if paganism had died out. This suggests it was no longer a big problem for the church.

Viking Arrivals

In the late 9th century, Scandinavian settlers came to Britain. They brought their own similar pre-Christian beliefs, called Norse paganism. No pagan worship sites from these settlers have been found by archaeologists. However, some place names suggest possible examples. For instance, Roseberry Topping was once called 'Hill of Óðin'.

Many pendants shaped like Mjolnir, the hammer of the god Thor, have been found. This shows Thor was likely worshipped by the Anglo-Scandinavian people. Some experts think only Odin and Thor were actively worshipped.

Archaeological finds, especially burials, show the arrival of Norse paganism. New Scandinavian burial styles appeared. These were different from Christian churchyard burials. Norse stories are also seen on stone carvings, like the Gosforth Cross.

The English church had to convert these new Scandinavian people. It's not clear how they did it. But it seems the settlers became Christian within a few decades.

Historian Judith Jesch suggests these beliefs survived as "cultural paganism." This means people knew about old myths, but it wasn't an active religion. It was more about their cultural background. For example, many Norse myths are in poems for King Cnut the Great. He was an 11th-century Anglo-Scandinavian king who was Christian.

Old Beliefs in Later Stories

Even after Christianity was adopted, many old customs continued. Some experts believe parts of Anglo-Saxon paganism became foundations for Anglo-Saxon Christianity. Old beliefs influenced folklore in the Anglo-Saxon period. This kept them alive in popular religion. The change to Christianity didn't erase old traditions. Instead, it often mixed them. The Franks Casket shows this, with both pagan and Christian stories.

Both church and government leaders spoke out against non-Christian practices. They condemned worshipping wells, trees, and stones. This continued into the 11th century. However, many of these condemnations were around the year 1000. This might mean they were reacting to Norse pagan beliefs, not older Anglo-Saxon ones.

Some English folklore from the Middle Ages is thought to come from Anglo-Saxon paganism. For example, the Yule log custom was believed to be a leftover. But some research suggests it came from Flanders in the 17th century. The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance is also sometimes linked to Anglo-Saxon paganism. The antlers used in the dance are from the 11th century. They likely came from Norway, as reindeer were gone from Britain by then.

Anglo-Saxon Stories and Gods

How the World Was Seen

We know little about how Anglo-Saxon pagans saw the universe. Some experts think each community had its own ideas. But there might have been a shared basic system. The later Nine Herbs Charm mentions seven worlds. This might be a hint about older pagan beliefs.

Bede said the Christian king Oswald of Northumbria won a battle at a sacred place called Heavenfield. This name might refer to a pagan belief in a heavenly plain. The Anglo-Saxon idea of fate was called wyrd. Some debate if this was a pagan idea. It might be linked to the Norse idea of three sisters, the Nornir, who control fate. It's possible Anglo-Saxons believed in an end of the world, like the Norse myth of Ragnarok.

Some scholars also think Anglo-Saxons might have believed in a world tree. This idea might come from a common ancient Indo-European belief. But any Anglo-Saxon world tree would likely be different from the Norse one.

Gods and Goddesses

Anglo-Saxon paganism was a religion with many gods. Christian writers usually didn't write about these gods. The Old English words for a god were ēs and ōs. These might be found in place names like Easole ("God's Ridge").

The god we know most about is Woden. Signs of his worship are found widely in England. Place names starting with Wodnes- or Wednes- are thought to refer to Woden. Examples include Woodnesborough and Wansdyke. Woden's name also appears in the family trees of royal families. This suggests he was later seen as a royal ancestor after Christianity arrived. Woden also leads the Wild Hunt. He is mentioned as a magical healer in the Nine Herbs Charm. He is similar to the Norse god Óðinn. His name is also the basis for Wednesday.

Some think Woden was also called Grim. This name appears in place names like Grimspound and Grimes Graves. In Norse myths, Odin is also called Grímnir. However, there are more Grim names than Woden names. So, Grim might not always have been linked to Woden.

The second most common god seems to be Thunor. The hammer and the swastika might have been his symbols. These symbols are found in Anglo-Saxon graves. Many Thunor place names include lēah (wood or clearing). Examples are Thunderley and Thundersley.

A third Anglo-Saxon god is Tiw. He might have been a war god. Some think Tiw was a distant creator god. His name is found in place names like Tuesley and Tysoe. The "T"-rune on some weapons might refer to Tiw. His name is also the basis for "Tuesday."

Perhaps the most important female god was Frig. We have little proof of her worship. She might have been a goddess of love or parties. Her name is suggested in place names like Frethern and Freefolk.

The East Saxon royal family claimed to come from Seaxnēat. He might have been a god. The monk Venerable Bede also mentioned two goddesses: Eostre, celebrated in spring, and Hretha.

Anglo-Saxon texts mention idols. No wooden carvings of human-like figures have been found in England. This is unlike Scandinavia. It's possible they were made of wood and didn't survive. Some human-like images have been found, but we can't link them to specific gods. A seated male figure on an urn lid might be Woden. Swastikas on urns are sometimes linked to Thunor.

Spirits and Creatures

Many experts think Anglo-Saxon paganism believed in spirits. They thought the landscape was full of different spirits and non-human beings. These included elves, dwarves, and dragons. For pagans, most daily interactions might have been with these "lesser supernatural beings." These creatures might be similar to later English beliefs in fairies.

Later Anglo-Saxon texts mention ælfe (elves). They are shown as male but with some female traits. Elves seem to have been part of older pagan beliefs. This is seen in Anglo-Saxon names like Ælfred (modern "Alfred"), meaning "elf counsel." Place names also mention þyrsas (giants) and dracan (dragons). But these names might have appeared later, not just during the pagan period.

Old Stories and Poems

In pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon England, stories were told, not written. So, very few survive today.

The mythological smith Weyland is mentioned in poems like Beowulf. He also appears on the Franks Casket. His stories are better known from Norse myths.

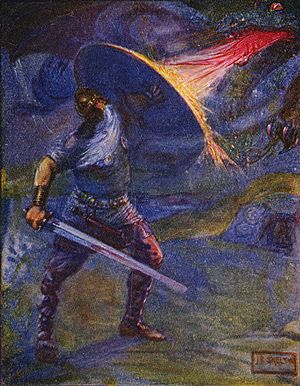

The only surviving Anglo-Saxon epic poem is Beowulf. It was written down by a Christian monk. The story is set in Scandinavia. It's about a warrior named Beowulf who fights monsters. He later becomes king and dies fighting a dragon.

For a long time, people thought Beowulf was a Scandinavian Christian tale. But in 1936, J. R. R. Tolkien argued it was an English poem. It was Christian, but it remembered pagan times. The poem mentions pagan practices like cremation. But it also talks about the Christian God and Bible stories. The author was likely a church person.

Some experts doubt if Beowulf tells us much about Anglo-Saxon paganism. Patrick Wormald said, "the harvest has been meagre." But others, like Richard North, think the poet knew more about paganism than he showed.

Religious Practices

Archaeologist Sarah Semple said Anglo-Saxon rituals included "votive deposits, furnished burial, monumental mounds, sacred natural phenomenon." They also had "constructed pillars, shrines and temples." These were similar to other pre-Christian religions in Europe.

Places of Worship

Clues from Place Names

Place names might point to where pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons worshipped. But we don't have clear archaeological proof for these sites. Two Old English words, hearg and wēoh, are thought to mean cult spaces. Hearg sites were usually on high ground. They might have been communal worship places for a group. Sarah Semple found that hearg sites often had activity from earlier periods. She suggested hearg might refer to something British in tradition.

Wēoh sites varied in location. Many were near old roads. David Wilson suggested wēoh meant a "small, wayside shrine." Some wēoh sites were linked to a person's name. This person might have owned or guarded the shrine.

Some place names combine a god's name with lēah (wood or clearing). This might mean there was a sacred grove for worship. Other names link a god's name with a high point like dūn or hōh. This suggests these spots were good for worship. Six examples link a god's name with feld (open land). These might have been holy places for farming.

Some Old English place names mention an animal's head. Examples include Gateshead ("Goat's Head"). These might have pagan religious roots. Perhaps they referred to a sacrificed animal's head on a pole. Or they could just be descriptions of the land.

Buildings for Worship

No pagan worship buildings from early Anglo-Saxon times have survived. We also don't have clear pictures or descriptions of them. But there are four mentions of pre-Christian cult buildings in Anglo-Saxon writings. Three are in Bede's Ecclesiastical History.

One is from a letter by Pope Gregory the Great. He said Christian missionaries should not destroy "the temples of the idols." Instead, they should clean them and turn them into churches. Another mention from Bede is about Coifi, a pagan priest. After becoming Christian, Coifi threw a spear into the temple at Goodmanham and burned it. The third account is about King Rædwald of East Anglia. He kept altars to both the Christian God and "demons" in one temple. Bede used the Latin word fanum for these places. He didn't say if they had roofs.

Archaeologist C. J. Arnold said that proof for shrines is "intangible." The best archaeological example of a cult building is Building D2 at Yeavering in Northumberland. Inside, ox skulls were found, possibly from sacrifices. Two post-holes might have held god statues. The building wasn't used for living, suggesting a special purpose.

Other possible temples have been found in cemeteries like Lyminge and Bishopstone. Pope Gregory suggested turning pagan sites into churches. But no firm archaeological proof of churches built on pagan temples has been found in England.

John Blair pointed to square enclosures from early Anglo-Saxon times. These often had standing posts. They were sometimes built on older prehistoric sites. He argued these were cultic spaces. They might have been based on older British traditions. Sarah Semple suggested these old burial mounds might have been seen as "the home of spirits, ancestors or gods."

Blair suggested that many cultic spaces didn't have buildings. He noted that some cultures use simple markers like logs or fabrics. These wouldn't leave archaeological traces. Arnold suggested that rituals might have happened in homes. He pointed to animal remains found in Anglo-Saxon settlements.

Sacred Trees and Stones

Old English writings have almost no mentions of sacred trees. But later Anglo-Saxon texts condemn worshipping trees, stones, and wells. In the 680s, Christian writer Aldhelm mentioned pagan use of pillars. He praised that many were turned into Christian worship sites. Aldhelm used the term ermula cruda ("crude pillars"). This might mean wooden totem poles or reused ancient standing stones.

It's hard to find where holy trees were. But some place names might refer to them. Blair suggested that names with bēam ("tree") or stapol ("post" or "pillar") could mean special trees. For example, Thurstable Hundred might come from 'Pillar of Þunor'. A large post found at Yeavering might have been religious. These poles could have been grave markers, group symbols, or sacred space markers. After Christianity, they could have become crucifixes.

Offerings and Sacrifices

Christian writings often said Anglo-Saxon pagans practiced animal sacrifice. Laws against pagan sacrifices appeared in the 7th century. The Paenitentiale Theodori set punishments for sacrifices. Archaeological finds show meat was often used in burials. Whole animal bodies were sometimes placed in graves. This suggests it was a common practice.

They seemed to prefer sacrificing oxen. This is suggested by both writings and archaeology. The Old English Martyrology says November (called Blōtmōnaþ or "sacrifice month") was for sacrifices. This was for offering to gods and getting food for winter.

| Old English | Translation |

|---|---|

| Sē mōnaþ is nemned Novembris on Lǣden, and on ūre ġeþēode "blōtmōnaþ", for þon þe ūre ieldran, þā hīe hǣðene wǣron, on þām mōnaþe hīe blēoton ā, þæt is þæt hīe betāhton and benemdon heora dēofolġieldum þā nēat þā þe hīe woldon sellan. | "The month is called Novembris in Latin, and in our language 'sacrifice month', because our ancestors, when they were heathens, always sacrificed in this month; that is, they took and devoted to their idols the cattle which they wished to offer." |

Priests and Kings

We know "virtually nothing" about pagan priests in Anglo-Saxon England. Only two mentions of pagan priests exist in surviving texts. One is about Coifi of Northumbria, mentioned by Bede.

Some experts believe kings acted as a link between gods and people. This is because there isn't much proof of a separate priesthood.

One burial at Yeavering might be a pagan priest's grave. It had a goat's skull and a wooden staff. Some think men buried in female clothes might have been magic-religious specialists. This is linked to an account by Tacitus about a male pagan priest wearing female clothing.

Anglo-Saxon society was structured with a chief or cyning (king). The king was a military leader, judge, and high priest. The tribe followed rules of proper behavior called sidu. The king was chosen from a royal family by an assembly of important people. The king was seen as having divine descent and bringing "luck" to the people. The importance of kingship is shown by the many words for "king" in Beowulf.

Burial Customs

Cemeteries are the most studied part of Anglo-Saxon archaeology. We know a lot about their burial customs from sites like Sutton Hoo and Spong Hill. There were about 1200 Anglo-Saxon pagan cemeteries.

There was no single way to bury the dead. Cremation was more common among the Angles in the north. Burial was more common among the Saxons in the south. But both were found everywhere. When cremated, ashes were put in an urn and buried, sometimes with grave goods. Burials usually faced west-east, with the head to the west.

Grave goods were common in both cremations and burials. Free Anglo-Saxon men were buried with at least one weapon. This was often a seax, but sometimes a spear, sword, or shield. Animal parts were also buried in graves. Most common were goat or sheep parts, but also ox parts. These items were likely food for the dead. Animal skulls, especially ox and pig, were also buried.

Archaeological digs show that small buildings were sometimes built in pagan cemeteries. These might have been shrines or sacred areas. Smaller structures were also built around individual graves. This suggests small shrines for the dead.

Later, in the 6th and 7th centuries, burial mounds appeared. Anglo-Saxons sometimes reused older mounds from earlier periods. We don't know why, but it might be from native British practices. Burial mounds remained important in early Anglo-Saxon Christianity. Many churches were built next to them.

Another burial type was ship burials. These were done by many Germanic peoples. Often, the body was placed in a ship that was burned at sea or on land. In Suffolk, ships were buried, not burned. Sutton Hoo is an example, believed to be the burial place of King Raedwald. Both ship and mound burials are described in the Beowulf poem.

It's hard to tell a pagan grave from a Christian one after Christianity spread.

Religious Festivals

All we know about pagan Anglo-Saxon festivals comes from Bede's book, De temporum ratione ("The Reckoning of Time"). Its goal wasn't to describe the pagan year. Little information can be checked with other sources. Bede gave explanations for festival names, but these might not be accurate.

The pagan Anglo-Saxons used a calendar with twelve lunar months. Sometimes, a 13th month was added to match the sun. Bede said the biggest pagan festival was Modraniht (meaning Mothers' Night). It was at the Winter solstice and marked the start of the Anglo-Saxon year.

In the month of Solmonað (February), Bede said pagans offered cakes to their gods. In Eostur-monath Aprilis (April), a spring festival honored the goddess Eostre. The Christian festival of Easter got its name from this month and goddess. September was Halegmonath, meaning Holy Month. November was Blōtmōnaþ, meaning Blót Month. It was for animal sacrifice to the gods and for winter food.

Historian Brian Branston said Bede's account shows a people closely connected to the changing year. They were "of the earth and what grows in it." James Campbell called it a "complicated calendar." He thought it would need "an organised and recognised priesthood" to manage it.

Symbols and Meanings

Various symbols appear on pagan Anglo-Saxon objects, especially grave goods. The swastika was common on cremation urns, jewelry, and weapons. Archaeologist David Wilson said it "undoubtedly had special importance." It was likely a symbol of the thunder god Thunor. On weapons, it might have offered protection. But its wide use might have made it just a decoration. Another symbol on artifacts, including swords, was the rune ᛏ. This rune stood for the letter T and might be linked to the god Tiw.

In the late 6th and 7th centuries, a symbol of a horn-helmeted man appeared. Tim Pestell said these were "one of the clearest examples of objects with primarily cultic or religious connotations." This symbol is also found in Scandinavia. On helmets and pendants, it might have been a protective charm. This figure is often thought to be Woden, but there's no strong proof.

Magic and Witchcraft

Some scholars now use the term "shamanism" for Anglo-Saxon paganism. Glosecki found signs of shamanic beliefs in later Anglo-Saxon writings. Williams also thought paganism had a shamanic part, based on burial rites. John Blair said it's "hard to doubt that something like shamanism lies ultimately in the background." But he noted it would be different from Siberian shamanism.

Anglo-Saxon pagans believed in magic and witchcraft. There were Old English words for "witch," like hæġtesse (which became "hag"). Belief in witchcraft was stopped in the 9th-10th centuries. The Laws of Ælfred (around 890) show this. Anglo-Saxons might not have seen a difference between magic and ritual, unlike modern society.

Christian leaders tried to stop witchcraft. The Paenitentiale Theodori condemned those who used "divinations" or "prophecies" like pagans. The word wiccan ("witches") is linked to healing rituals. One text says:

Some men are so blind that they bring their offering to earth-fast stone and also to trees and to wellsprings, as the witches teach, and are unwilling to understand how stupidly they do or how that dead stone or that dumb tree might help them or give forth health when they themselves are never able to stir from their place.

Pagan Anglo-Saxons also wore amulets. Many bodies were buried with them. David Wilson said they were part of their "world of 'belief'." One common amulet was the cowrie shell. It's thought to be a fertility symbol. These shells came from the Red Sea. Animal teeth, like boar, beaver, and even human teeth, were also used as amulets. Other amulets included amethyst and amber beads, quartz, and fossils. Amulets were much more common for women than men.

See Also

- Christianity and Paganism

- List of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |