Yeavering facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Yeavering |

|

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | NT935305 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority |

|

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WOOLER |

| Postcode district | NE71 |

| Dialling code | 01668 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Northumberland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| EU Parliament | North East England |

| UK Parliament |

|

Yeavering is a small village, also called a hamlet, in the north-east part of Northumberland, England. It sits by the River Glen, right at the edge of the Cheviot Hills. Yeavering is famous because it was once a very important Anglo-Saxon settlement. Archaeologists believe it was a royal home for the kings of Bernicia in the 600s AD.

People have lived in this area for a very long time, even during the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age periods. But it was in the Iron Age that a large settlement really grew here. During that time, a big hillfort was built on Yeavering Bell, which was a major center back then.

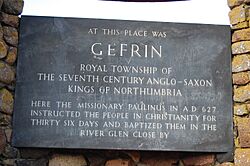

A famous monk named Bede (who lived from 673 to 735 AD) wrote about Yeavering in his book, Ecclesiastical History. He said that in 627 AD, a bishop named Paulinus of York visited the royal home, called Adgefrin. Paulinus spent 36 days there, teaching and baptizing people in the River Glen.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Yeavering first appeared in Bede's book in 731 AD as ad gefrin. This name comes from old British words: gevr meaning 'goats' and brïnn meaning 'hill'. So, Yeavering means 'hill of the goats'.

Yeavering's Landscape

Yeavering is located at the western end of a valley called Glendale. Here, the Cheviot foothills meet the flat, fertile land of the Tweed Valley. The most noticeable feature is Yeavering Bell, a hill with two peaks that is 1158 feet (353 meters) high. This hill was used as an hillfort in the Iron Age.

North of Yeavering Bell, the land drops down to a flat area called the 'whaleback'. This is where the Anglo-Saxon settlement was built. The River Glen flows through this area. In the past, much of the land around the whaleback was wet and boggy, making it hard to live on. Today, modern drainage has mostly fixed this, leaving only a few marshy spots. Strong winds often blow through the area, sometimes reaching gale or even hurricane force.

Ancient Settlements at Yeavering

Early People: Stone and Bronze Ages

Archaeologists have found signs that people lived in the Glen Valley during the Mesolithic period. These early Britons were hunter-gatherers. They moved around in small groups, looking for food and resources. They used stone tools, and some of these tools have been found in the Glen Valley.

Later, in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, people in Britain started to settle down. They formed permanent communities and began farming. Evidence of their activity, like 'ritual' pits and cremation burials, has also been found in the valley.

Iron Age and Roman Times

The Yeavering area was settled even before the Early Medieval period. During the British Iron Age, a large hill fort was built on Yeavering Bell. This fort was the biggest of its kind in Northumberland. It had stone walls around both peaks of the hill. More than a hundred roundhouses were built on the hill, showing that many people lived there. The local tribe was called the Votadini.

In the 1st century AD, the Roman Empire took over southern and central Britain. This period of Roman rule lasted until about 410 AD, when the Romans left Britain. Archaeologists have found Roman-British items near the roundhouses, including coins and pottery pieces.

Archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor thought that by the 1st century AD, the settlement on Yeavering Bell was "a major political center." It might have been important for the whole region between the Tyne and Tweed rivers.

Early Medieval Royal Settlement

In the Early Medieval period, the Yeavering area became home to Gefrin, a royal settlement in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia. It's been called an 'Anglo-British center' because it had influences from both native British people and Anglo-Saxons.

Why Yeavering?

Archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor believed that the kings of Bernicia ruled over two main groups of people. There were native Britons, who were descendants of the Roman-British population. And there were Anglo-Saxons, who had moved from Europe. He thought Anglo-Saxons lived mostly near the coast, while Britons were more common inland.

Hope-Taylor suggested that the Bernician kings had two main royal homes. One was at Bamburgh on the coast. The other was at Yeavering, which was in the British-dominated central area. This way, they could rule both groups of people.

He also thought that Yeavering was chosen because it had been an important place in the Iron Age and Roman times. Building a royal site there was like connecting to the area's old traditions. Plus, the soil around Yeavering was very good for farming, which was important for feeding a large settlement.

Buildings at Gefrin

Archaeologists dug up many timber buildings at Gefrin in the mid-1900s.

- Building A1 was a large hall with doors on every wall. Its timber walls were very thick and set deep in the ground. It burned down twice but was rebuilt each time.

- Building A2 was a Great Hall with dividing walls inside. It wasn't destroyed by fire but was taken down on purpose, probably to make way for new buildings. This hall was built on top of an older prehistoric burial pit.

- Building A3 was another Great Hall, even bigger than A1. It also burned down but was rebuilt.

- Building A4 was similar to A2, but with only one dividing wall.

- Building A5 was smaller, like a "house or cottage," with a door on each wall. Buildings A6 and A7 were similar in size but older.

- Building B was another hall with an annex on its western side.

Other buildings included:

- Building C1: A rectangular pit, possibly a water tank, which showed signs of burning.

- Building C2: Another rectangular building with four doors, but no fire damage.

- Building C3: A larger rectangular timber hall with unusual double rows of post-holes.

- Building C4: The largest hall in this group, which had been rebuilt after a fire.

Building D1 seemed to have been built with some mistakes, ending up as a diamond shape instead of a rectangle. It likely collapsed or was taken down soon after it was built, and another hall with wobbly walls replaced it.

Building D2 was built to match D1 in size and shape. It was later taken down and replaced by a "massive and elaborate" new version. Building D2 is thought to be a temple or shrine for Anglo-Saxon gods. Archaeologists believe this because they found no normal household items there. Instead, they found a large pit filled with animal bones, mostly ox skulls.

Building E was in the center of the settlement. It had nine circular trenches, suggesting it was a large tiered seating area facing a platform, perhaps for a king's throne.

There was also a Great Enclosure, a circular earthwork with a building (Building BC) inside. This enclosure might have been a meeting place or a cattle pen.

Burials at Yeavering

Archaeologists found an Anglo-Saxon burial from the early 600s, called Grave AX, among the buildings. It contained the outline of an adult body lying east-west. Metal objects and a goat skull were found with the body. One metal object was a seven-foot-long bronze-bound wooden pole, possibly a ceremonial staff.

A group of graves, called the Eastern Cemetery, was found at the eastern end of the site. This cemetery was used for a long time, showing five different phases of burials.

Bede's Story of Yeavering

One of the best sources of information about Anglo-Saxon England comes from a monk named Bede (672/673-735). Bede lived in a monastery in Jarrow. He is often called "the Father of English History." Around 731 AD, Bede finished his most famous book, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People).

In this book, Bede wrote about a royal town called Ad Gefrin, located by the River Glen. He described how King Edwin of Bernicia, after becoming a Christian, brought a preacher named Paulinus to Ad Gefrin. Paulinus then converted the local people from their old pagan religion to Christianity.

Bede wrote: "So great was then the passion for the faith [Christianity]... that Paulinus, coming with the king and queen to the royal country-seat, which is called Ad Gefrin, stayed with them thirty-six days, fully busy teaching and baptizing. During these days, from morning till night, he did nothing else but teach the people... in Christ's saving word; and when taught, he washed them with the water of cleansing in the river Glen which is close. This town, under the following kings, was left, and another was built instead of it, at the place called Melmin."

Archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor was sure that Yeavering was indeed Bede's Ad Gefrin.

How Yeavering Was Discovered

In the early 1900s, Dr. John Kenneth Sinclair St Joseph, a Cambridge University expert in Aerial Photography, flew over Yeavering. He was taking pictures of Roman forts. During a very dry period, he photographed some unusual marks in oat fields. These marks, called cropmarks, showed outlines of buried structures.

In 1951, archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor looked at these photos. He thought they might show the 7th-century royal town that Bede called Ad Gefrin. He started planning to dig at the site. In 1952, the site was almost damaged by nearby quarrying. But Sir Walter de L. Aitchison told St Joseph, who was then the Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments. St Joseph stepped in to protect the site, allowing Hope-Taylor to start his excavations in 1953. His first digs ended in 1957. He returned to dig again from 1960 to 1962.

Hope-Taylor's excavations revealed many important features:

- A large, double-fenced area called the Great Enclosure. It wasn't for defense but likely a meeting place.

- Several rectangular buildings, called Great Halls, with very deep foundations. Some were as large as 300 square meters.

- A set of nine curved trenches, which Hope-Taylor thought was a tiered seating area, like an auditorium, that could hold about 300 people.

- Other rectangular buildings in different parts of the site.

- Human burials at both ends of the site, some placed in older prehistoric burial mounds.

These buildings, especially the Great Halls, were very well built. They were made with carefully measured timbers. Hope-Taylor believed that a standard unit of measurement, the 'Yeavering foot' (about 300 mm), was used for all the buildings and the site's layout.

Hope-Taylor saw Yeavering as a place where native British people and the new Anglian rulers met and mixed. He thought the site showed a long history of use, not just from the 600s. He believed that the Bernician kings worked peacefully with the Britons inland, rather than just fighting them.

Evidence for this idea included:

- The buildings showed different styles, from British to a mix of British and Anglo-Saxon.

- The burials seemed to continue old traditions from the Bronze Age.

- The Great Enclosure also seemed to have developed from older local traditions.

The auditorium building was unique in post-Roman Britain. Hope-Taylor thought it was like a Roman theater, but built from timber. This showed Roman influence.

Building D2a, thought to be a temple, had cattle bones piled up, suggesting animal worship. Other graves, like one with a child buried with a cow's tooth, also hinted at animal cults. A goat's skull in a grave near Great Hall A4 might relate to the name 'goat's hill'.

The site also had two prehistoric burial mounds, which were reused. Posts were put in their centers, and burials were placed around them. Some burials were pagan, but Yeavering was also where Christianity arrived. Bede's story tells of the conversion in 627 AD.

Hope-Taylor believed that a fire that destroyed Great Hall A4 and other buildings was due to an attack after King Edwin died in 633 AD. Another fire was blamed on King Penda of Mercia in the 650s. He thought the four Great Halls in Area A were built by four different kings: Æthelfrith, Edwin, Oswald, and Oswiu. However, there's no written proof that Yeavering was attacked in 633 or the 650s.

The Gefrin Trust

In April 2000, archaeologist Roger Miket learned that the site of Ad Gefrin was for sale. He bought the land to protect it.

Roger's goal was to set up an independent charity to manage the site. This charity, called The Gefrin Trust, was formed in 2004. It includes experts from local government, English Heritage, and universities. Community involvement is also very important to the Trust.

The Trust meets regularly to plan for the site's future. They have improved public access by fixing fences, adding new gates and paths, and putting up information panels. The Trust has a very long lease for the site and makes all management decisions.

Local artist Eddie Robb created the beautiful goat-head gateposts and other carvings you can see at the site today. These carvings also include a Saxon warrior's head and the 'Bamburgh Beast'. They are inspired by Brian Hope-Taylor's own drawings.

The Gefrin Trust has a website, www.gefrintrust.org, with news and information. You can find out about their work, like using special equipment to find more structures underground. They also have new aerial photos and information about objects found during Hope-Taylor's excavations. You can even watch a TV program by Brian Hope-Taylor about the site.

The Trust held its first Open Days at the site in June 2007. They wanted to meet visitors, explain how they find things underground, and give guided tours. They even offered a guided walk up Yeavering Bell.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |