Burial in Anglo-Saxon England facts for kids

Burial in Anglo-Saxon England is all about how the Anglo-Saxons buried their dead. This happened between the mid-400s and the 1000s CE in early England. They used two main ways to bury people: cremation (burning the body) and inhumation (burying the body in the ground).

Interestingly, rich and poor people were often buried together in the same cemeteries. Both types of burials usually included grave goods. These were items like food, jewelry, and weapons placed with the dead. Bodies, whether burned or not, were buried in different places. These included regular cemeteries, burial mounds (big piles of earth), or sometimes even ship burials.

Burial customs changed over time and in different parts of Anglo-Saxon England. Early Anglo-Saxons followed a pagan religion. Their burials showed this. Later, in the 600s and 700s CE, they became Christians. This change also affected how they buried people. Cremation stopped, and only inhumation was used. Burials then mostly happened in Christian cemeteries next to churches.

In the 1700s, people interested in old things, called antiquarians, started digging up these burials. More scientific digs began in the 1900s with the growth of archaeology. Famous Anglo-Saxon burial sites found include Spong Hill in Norfolk and the amazing Sutton Hoo ship burial in Suffolk.

Contents

History of Anglo-Saxon Burials

The early Anglo-Saxon period in England lasted from the 400s to the 700s CE. During this time, burying the dead was a common practice. Archaeologists believe that how the dead were treated was very important to Anglo-Saxons. This is because there were many different ways of burying people.

These different burial styles showed things like a person's importance, wealth, gender, age, or family group. Early Anglo-Saxon graves were very different from those in Roman Britain before them. Romans usually buried bodies, though some cremations did happen.

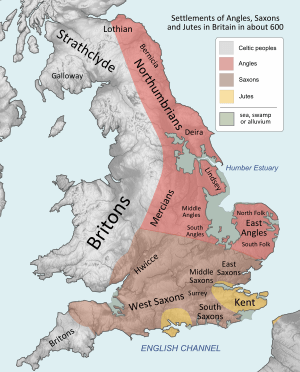

Around the 400s CE, Germanic-speaking tribes arrived in Britain. These included the Angles, Jutes, and Saxons. They brought their own culture, language, and pagan religion. Their way of life became common in much of eastern Britain. The people already living there, the Romano-Britons, either joined this new culture or moved west.

The Anglo-Saxons brought their own varied burial customs. These were different from the British people in western and northern Britain. Their customs were more like those in pagan Europe. However, not everyone buried in the Anglo-Saxon way was from these migrating tribes. Some might have been Romano-British people who adopted the Anglo-Saxon culture. For example, at Wasperton in Warwickshire, Anglo-Saxon graves were found next to Romano-British ones.

In the 600s, Christian missionaries came to Anglo-Saxon England. This led to big changes in burial practices. Cremation, which was common in the 400s and 500s, quickly stopped. The Christian Church didn't mind grave goods at first. But over time, people started to think they weren't important. Still, some rich grave goods continued to be buried until the 700s.

Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Styles

Burying Bodies (Inhumations)

The most common way Anglo-Saxons buried their dead was by inhumation. This means placing the body directly into the ground. These burials are a "super important" source for understanding early medieval society. In many cases, the soil has kept the bodies well preserved. This allows archaeologists to learn a lot from them.

From Anglo-Saxon inhumations, scientists can find out a person's gender or age. They can also learn about their health or how they lived. Special tests can even tell which region a person grew up in.

Graves for Anglo-Saxon inhumations varied a lot in size. Some were just shallow holes. Others were large pits, over 2 meters long and 1 meter deep. Most Anglo-Saxon inhumations were for single people. But it was "fairly common" to find graves with more than one person. These often contained a couple, or an adult and a child. Sometimes, three or more people were buried in one grave.

Burning Bodies (Cremations)

Besides inhumation, early Anglo-Saxons often cremated their dead. They burned the bodies and then buried the ashes in an urn. Cremation became less popular in the 600s. But it was still used at some places, like St Mary's Stadium in Southampton.

Archaeologist Audrey Meaney thought cremation was done to "free the spirit" from the body after death.

Burial Urns and Grave Goods

Anglo-Saxon burial urns were usually handmade from pottery. They often had different designs. These included bumps, stamped patterns, and carved lines. Sometimes they had freehand drawings. A very important design was the swastika. This symbol was on cremation urns, weapons, brooches, and jewelry.

Archaeologist David Wilson said the swastika "definitely had special meaning." He thought it might be a symbol for the pagan god Thunor. But he also thought it might have become just a decoration over time. Another symbol found on urns is the rune ᛏ. This letter T was linked to the god Tiw.

Sometimes, urns had lids. The most fancy one, from Spong Hill, has a sitting human figure with its head in its hands. Some urns used stones as lids. There were also "window urns" with glass pieces in the pottery. These were found at places like Castle Acre and Helpston. In a few rare cases, Anglo-Saxons reused older Roman urns for burials. Sometimes, bronze bowls were used instead of pottery urns. Examples were found at Sutton Hoo and Snape.

Like inhumations, cremated remains sometimes had grave goods. However, only about half of known cremations had them. Sometimes, these items were burned with the body. Then they were placed in the urn. Other times, grave goods were put into the urn without being burned. This meant they stayed whole.

Common grave goods in cremation graves were "toilet tools." These included bronze and iron tweezers, razors, blades, and ear-scoops. Some were full-sized, but others were tiny and not for real use. Bone and antler combs were also common. Some were broken on purpose before being buried.

Where Anglo-Saxons Were Buried

Cemeteries

Archaeologists have found about 1,200 Anglo-Saxon cemeteries across England.

Digs have shown that some pagan cemeteries had structures or buildings inside them. David Wilson noted that these might have been "shrines or sacred areas." In some cases, smaller structures were built around individual graves. This might mean they were small shrines for the person buried there. At Apple Down in Sussex, four-post structures were found over cremations. Experts think these were small, roofed huts holding the ashes of a single family.

Barrow Burials

In the late 500s, Anglo-Saxons started a new burial custom for rich and powerful people. They buried them in tumuli, also called barrows or burial mounds.

This practice was adopted from the Merovingian dynasty in Francia (modern France). In the 500s, they had more influence over the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Kent. This led to a marriage between the two groups. The Kentish leaders then started using barrow burials. From Kent, this practice spread north to other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Some also think Anglo-Saxons might have learned this from native Britons.

Barrows were built for burials in Britain long before the Anglo-Saxons arrived. This happened during the Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Romano-British times. Often, Anglo-Saxons reused these older mounds instead of building new ones. Barrow burials continued through the 600s but mostly stopped by the 700s.

Ship Burials

Another type of burial was ship burials. Many Germanic people in northern Europe used these. Often, the body was placed in a ship. The ship was then sent out to sea or left on land and set on fire. In Suffolk, however, ships were not burned but buried. This is what happened at Sutton Hoo. It is believed to be the resting place of King Rædwald of the East Angles. Both ship and mound burials are mentioned in the Beowulf poem.

Grave Goods

Both pagan and Christian Anglo-Saxons buried their dead with grave goods. Early Anglo-Saxons, who followed pagan beliefs, placed these items with both buried and cremated bodies.

Howard Williams suggested that grave goods helped people remember things in early medieval society.

Grave goods can tell archaeologists about cultural links and trade. For example, at Buckland Cemetery near Dover, over half the brooches found were from continental Europe. This shows the connections between the Kingdom of Kent and the Frankish area.

Middle Anglo-Saxon Period Burials

The Middle Anglo-Saxon period is from about 600 to 800 CE. Burial practices from this time are not as well understood as earlier or later periods. The first person to identify a cemetery from this time was James Douglas in the late 1700s. He found Christian symbols on items in Kentish barrow cemeteries. He realized these were Anglo-Saxons who had become Christian but lived before churchyard burials were common.

Later, archaeologist T. C. Lethbridge found more Middle Anglo-Saxon cemeteries in Cambridgeshire. He noticed they didn't have "pagan" items like weapons. He thought the people buried there were early Anglo-Saxon Christians.

Archaeologist Helen Geake divided burials from this period into four types. These were furnished, unfurnished, princely, and deviant. Some cemeteries had only one type, but others mixed them. The famous Middle Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Sutton Hoo had three types of burials.

The conversion of Anglo-Saxon England to Christianity in the 600s helped explain many changes in burial practices. For example, grave goods slowly disappeared. Also, bodies were increasingly buried facing west to east. These changes were linked to Christian beliefs about the afterlife.

Final Phase Burials

Cemeteries from this period are sometimes called "Final Phase." This term was created by archaeologist Edward Thurlow Leeds in 1936. He saw these cemeteries as the last sign of the pagan way of life before Christianity took over. In 1963, Miranda Hyslop listed what she thought defined Final Phase burials. These furnished burials are typical of cemeteries from the 600s and early 700s.

Boddington listed eight features of Final Phase burials. First, new cemeteries were started under Christian influence. Second, these cemeteries were often near settlements, unlike earlier ones. Third, almost all burials were inhumations, with very few cremations.

Fourth, these inhumations usually faced west to east. Fifth, some graves were in or under barrows. Sixth, many graves had few or no grave goods. Seventh, the items found were mostly useful clothing items or small personal tokens. Finally, some grave goods, like crosses, had Christian meaning.

There were different structures in and around the graves. These included beds or chambers inside the grave. Outside, there might be mounds, potholes, or boat parts.

Final Phase burials showed a growing difference in wealth. Most had grave goods, but fewer items than in the Early Anglo-Saxon period. The items themselves also changed. Brooches and long bead necklaces became less common in women's graves. Weapons became less common in men's graves. Men's graves often had small buckles, knives, and shoelace tags. Women's graves typically had pins, chatelaines (chains for tools), and necklaces with small beads or gold pendants.

The decline in grave goods was sometimes blamed on the Christian Church. But this idea is often questioned. There are no old laws from this time that forbid burying grave goods. Also, the decline was slow, not a sudden stop.

Another idea is that inheritance rules changed. Weapons, for example, might have been passed down to family instead of being buried. A third idea is that people wanted to save resources. They might have wanted to keep valuable items in use rather than burying them. This could be linked to more trade and new trading places like Ipswich.

The types of grave goods also spread over larger areas. This might mean that Anglo-Saxon people started to see themselves as part of a bigger group, the English.

Elite or Rich Burials

A special type of burial in Middle Anglo-Saxon England is called a "Rich Burial" or "Princely Burial." These have many high-quality grave goods. They are often found under a barrow mound. However, archaeologists don't have one clear definition of what makes a burial "princely." These rich burials are similar to other Final Phase burials in how the body is placed and the structures around the grave.

The most famous are male burials from the early 600s. These likely showed off kingly power. Sutton Hoo is the most famous. Other important examples include the ship burial at Snape and the 'Prittlewell Prince'. Later in the 600s, there were more lavish female burials, like at Swallowcliffe Down.

Unfurnished Burials

Some cemeteries from the 600s and 700s mostly contain unfurnished burials. This means they had few or no grave goods. These burials have been found in both country areas and towns.

The practice of unfurnished burial might have come from other parts of Britain, like Ireland or Northumbria.

Deviant Burials

These burials usually have very few or no grave goods. In some cases, like at Sutton Hoo, these burials were made around a barrow.

Late Anglo-Saxon Period Burials

In nearby Francia, laws in the late 700s and early 800s stopped the use of older, non-Christian cemeteries. They stressed the need for churchyard burials. This rule might have confirmed ideas already held by the Anglo-Saxon Church.

Archaeologist Andy Boddington said the change from rich graves in the Early Anglo-Saxon period to plain ones in the Late Anglo-Saxon period was "one of the most dramatic" changes.

After 900, a special ceremony for consecrating churchyards was created. It became required for people to be buried in the churchyard of their parish. Churchyards started to be enclosed in the 900s and 1000s. Church leaders also started to earn money from burials. They received a fee for the burial and for prayers for the dead.

Christian teaching said that after death, a person's soul would be judged. Those who were baptized and did good deeds could go to Heaven. Those who didn't would go to Hell. Texts from this time show that church leaders disagreed. Some thought judgment happened right after death. Others thought all souls waited for Judgement Day. The idea of Purgatory, a place between Heaven and Hell, had not yet been developed.

By the 700s, burying people in their clothes mostly stopped, except for priests. Most people were buried in a white cloth, called a shroud. This was like how Jesus Christ was described as being buried in the Gospels.

Graveyards

The usual way for graveyard burials was orderly. Bodies were buried facing west to east, without cutting into other graves.

Grave Markers

A tradition began of marking important graves, especially those of church leaders. These markers included flat slabs over the grave and tall crosses. Many of these crosses still stand today. Surviving marker stones show that different regions had their own styles. In Eastern England, Scandinavian art influenced many of them.

In areas of Scandinavian settlement in northeast England, hogback tombs were made. Scandinavian settlement also led to some furnished burials under barrows again. An example is at Ingleby.

Saints' Burials

Bede describes the burial of St Cuthbert. This account is seen as "an extreme case" but "not unusual for those considered holy."

Finding and Digging Up Burials

Early Investigations (Antiquarian)

Even with earlier digs, archaeologist Sam Lucy said the first real Anglo-Saxon cemetery excavators were two Kentish churchmen. The first was Reverend Bryan Faussett. Between 1759 and 1773, he dug at several cemeteries in Kent. He found about 750 graves and kept detailed notes. But like others, he wrongly thought they were Roman-British. After he died, his notes were published in 1856 by Charles Roach Smith.

The second Kentish churchman was James Douglas. He dug at sites like Chatham Lines from 1779 to 1793. He published his findings in a book called Nenia Britannica. Douglas was the first to realize these burials were Anglo-Saxon, not Roman-British. He figured this out because they were near villages with Anglo-Saxon names. Also, they were found all over Britain where Anglo-Saxons lived, but not in parts of Wales they didn't control.

Modern Archaeological Investigations

Some early investigators tried to dig up and list Anglo-Saxon grave sites. But generally, these sites were often damaged in the 1700s and early 1800s. Little effort was made to study them properly. Because the Society of Antiquaries couldn't help, Charles Roach Smith and Thomas Wright started the British Archaeological Association (BAA) in 1843. They held their first meeting in Canterbury. The BAA pushed for better rights for British archaeology. They wanted it to be legally protected and recognized by big institutions.

In September 2020, archaeologists announced a new discovery. They found an Anglo-Saxon cemetery in Oulton, near Lowestoft. It had 17 cremations and 191 burials from the 600s. The graves contained items like small iron knives, silver coins, wrist clasps, and strings of amber and glass beads.

See also

- Bed burial

- Eaves-drip burial

- List of Anglo-Saxon bed burials

- List of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries

- Prittlewell royal Anglo-Saxon burial

- Norse funeral

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |