Street House Anglo-Saxon cemetery facts for kids

Reconstruction from Kirkleatham Museum of the body of the Street House "Saxon Princess" in her bed

|

|

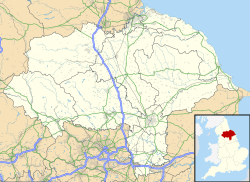

| Location | Loftus, North Yorkshire, England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 54°33′46″N 00°51′26″W / 54.56278°N 0.85722°W |

| Type | Necropolis |

| History | |

| Periods | Anglo-Saxon |

The Street House Anglo-Saxon cemetery is an Anglo-Saxon burial ground. It dates back to the late 600s AD. This ancient burial site was found at Street House Farm near Loftus, in Redcar and Cleveland, England.

Archaeologists found the cemetery after aerial photos showed an Iron Age enclosure. Digs between 2005 and 2007 uncovered over 100 graves. They also found remains of several buildings. Many pieces of jewellery and other items were discovered. These included jewels worn by a young, important Anglo-Saxon woman. She was buried on a bed and covered by an earth mound.

We don't know who the woman was. But the items and cemetery layout are like others found in eastern and southeastern England. The cemetery shows signs of both Christian and pagan traditions. This suggests it was used during a time when Christianity was spreading. However, older pagan customs were still practiced. Archaeologists think the woman and some others might have moved from the south. Bed burials were more common there. The cemetery was likely used for only one generation, then abandoned. The finds are now at Kirkleatham Museum in Redcar. They have been on display since 2011.

Contents

Discovering the Street House Cemetery

The area around Street House Farm has been important to archaeologists for many years. It's located on Upton Hill, northeast of Loftus. In the past, older sites were found here. These included a Neolithic burial mound from about 3300 BC. A round burial mound from the Bronze Age was built on top of it.

In 1984, archaeologist Blaise Vyner found a strange structure. He called it the "Street House Wossit." This was a circle of 56 wooden posts from around 2200 BC. Its purpose is unknown, but it was likely a religious site.

How the Cemetery Was Found

Archaeologist Steve Sherlock, who worked on earlier digs, returned to the site. Aerial photographs showed a rectangular Iron Age enclosure. Initial digs in 2004 thought the site was only Iron Age or Roman-British.

More detailed work began in 2005. A geophysical survey uses special equipment to look underground. This survey showed a large Iron Age roundhouse inside the enclosure. The digs then uncovered three roundhouses and Iron Age ditches. To everyone's surprise, they also found pits that were graves. These graves dated to the Anglo-Saxon period.

Many items from between 650 and 700 AD were found. No bones survived because the soil was acidic. Thirty graves were found during this first excavation.

Uncovering More Graves

In 2006, archaeologists looked for a settlement linked to the graves. They found another twelve graves. It became clear the cemetery was much bigger than first thought. In 2007, they surveyed the whole site. By the end of 2007, 109 graves were found. They formed a unique square shape around a central mound. There was also a bed burial and a building that might have been a mortuary.

Later digs in 2010 and 2011 explored nearby Neolithic and Bronze Age mounds. In 2012, a new excavation found a large Roman villa. It dated to about 370 AD and was only about 100 meters south of the Saxon graves. This villa was likely part of a large farm estate.

How the Graves Were Arranged

The cemetery has neat rows of graves. They are lined up east to west. The area is almost square, about 36 by 34 meters. This layout is unique among Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. The enclosure around the cemetery was much older, from about 200 BC. Placing the cemetery here might have been a way to connect to the past. The old enclosure would still have been clearly visible in Saxon times. The cemetery's design seems to copy the older enclosure's shape. Its main entrance also lined up with the enclosure's entrance.

Most graves were very orderly. They were in double rows on the north and south sides. Each grave was 2.5 meters apart east-west and 2 meters apart north-south. None of them cut into each other. This careful arrangement suggests the cemetery was planned in advance.

Different Burial Styles

About 22 percent of the graves don't fit the main square plan. Some of these might be older, possibly Roman-British. Others might have been made by different groups of people in Saxon times. The most famous of these "non-standard" burials is the "Saxon Princess." Her grave is near the center of the enclosure.

While her grave has amazing finds, it might not have been the most important. A second, larger mound stood nearby. It was partly surrounded by a ditch. No burial was found inside it. This mound might have been a memorial for an important person. The "Saxon Princess" and other burials in the northeast were arranged in a curve around this mound. This suggests it was a central point of the cemetery.

The graves are mostly aligned east-west. This often suggests Christian burials. However, other evidence from the cemetery shows both Christian and pagan traditions. The individual graves were usually 2 meters long, 0.8 meters wide, and about 0.6 meters deep. They had rounded corners and flat bottoms.

The bodies were not in coffins. People were buried in their clothes with personal items or gifts. No bodies survived, but their size suggests most graves were for women. They were laid out fully stretched. Some graves were too small for an adult. These might have held bodies buried in a crouched position. Different burial methods could show different family groups or beliefs.

Some graves have plain triangular stones at one end. These stones are not carved with names like in Christian cemeteries. They are similar to markers found in pagan burial sites. Some graves have holes from wooden poles. These poles might have been markers or supported structures inside the graves. This is unusual for northern England but seen in places like Kent.

Buildings in the Cemetery

Several buildings stood within the cemetery. A large rectangular building, identified by postholes, was on the east side. It might have been a chapel or shrine. A smaller grubenhaus (a sunken building) was also nearby. This might have been a mortuary chapel. An Iron Age roundhouse was once in the northwest. It was not standing when the cemetery was created. All these buildings were on a ridge, visible to travelers coming from the south.

The cemetery seems to have been set up at one time and used for a short period. Mourners likely entered from the south. They would gather in the empty southwestern area. Then they would go to the shrine for burial rites. After placing the deceased in a grave, they might have left through the eastern entrance. Different groups might have used different entrances, which could explain why some graves don't fit the main plan.

Amazing Artefacts Found

Archaeologists found items in 64 graves, which is 59 percent of all graves. Some items help tell if the person was male or female. Male graves often have weapons and tools. Female graves usually have jewellery, shears, and chatelaines (belt hooks for keys or small tools).

Thirty-four graves had gender-specific items. Nineteen were for females, and fifteen for males. Female graves were mostly in the north and west. Male graves were in the south and east. Paired graves might have been for married couples, a pattern seen in other Saxon cemeteries.

Jewellery and Weapons

Fifteen graves had beads, and iron items were in 25 graves. A seax (a type of short sword) was found in grave 29. It was the only weapon in the cemetery. Finding such weapons in graves is rare. They were usually passed down through families. This seax was about 55 cm long but broken. Its blade had a punched pattern. Smaller knives were found in 19 graves. Other iron items like belt buckles and keys were also present. In grave 81, two whetstones for sharpening knives were found with the knives.

Many types of jewellery, beads, and charms were discovered. One hundred beads were found in 16 graves. Only two graves had more than 10 beads. This shows how styles changed. In the 500s, women wore many plain beads. By the mid-600s, the fashion was for a few high-quality beads.

A very unusual find was in grave 21. It was a necklace with eight beads and two Iron Age gold coins. These coins were made by the Corieltauvi tribe in modern Lincolnshire between 15 and 45 AD. This was before the Roman conquest of Britain. Holes were drilled in the coins to turn them into jewellery. They were over 600 years old when buried! Their excellent condition suggests they weren't used as money for long. They might have been part of a hidden treasure found by the Saxons. Finding Roman coins in a Saxon grave from this time is unique to Street House. They were likely valued for their cross-shaped designs.

- Jewellery found in the Street House cemetery

An amazing gold pendant was found in grave 10 with three beads. They were likely worn together on a chain. The pendant is small, only 27 mm wide. But it has detailed gold filigree in figure-of-eight shapes. This design is typical of jewellery made after 650 AD. Similar pieces have been found in Yorkshire.

In grave 70, a gold pendant 44 mm wide was found. It also has fancy filigree work. It includes four round settings, each with a red gemstone. Only two stones remain. Several beads were found with this pendant, likely part of the same necklace.

The "Saxon Princess" Bed Burial

The most important grave, with the most spectacular items, was near the cemetery's center. Grave 42 was a deep, wide pit. A very important person was buried there on a wooden bed with iron fittings. The body was likely a high-ranking noblewoman, possibly even royalty. The amount and quality of jewellery show she was at the top of Anglo-Saxon society.

Bed burials are very rare. Only about a dozen are known in the UK. The Street House one is the most northern known.

The Bed and Jewels

No body or bed remains today. But surviving items and 56 iron pieces that held the bed together helped reconstruct it. The bed was made from ash wood. It was held together with iron plates, staples, and decorative scrolls. It measured 1.8 by 0.8 meters. It might have had an ornamental roof or canvas cover. Traces of cloth and grass were found on some nails. This suggests what the mattress might have been like. Two iron pieces showed repairs. This means the bed was used before the burial. It might have been the woman's own bed or another important bed. It was likely taken apart, moved to the cemetery, and put back together for the burial.

The jewellery includes three gold pendants, two glass beads, one gold wire bead, and a piece of a jet hair pin. The pendants and beads were probably part of a necklace. Two pendants are gold cabochons with jewels. The third is a very detailed shield-shaped jewel. It has 57 red garnets and a larger scallop-shaped gem in the center. The garnets sit on thin gold leaf to make them shine more. This jewel might have been made from older recycled jewellery. The garnets are all different sizes and shapes.

The quality of this jewel is amazing. It's as good as items found at the famous Sutton Hoo cemetery in Suffolk. Its design is unique. The person who made it must have been one of the best craftworkers of the time. Its scallop shape is an important link to early Christianity. The scallop was a symbol of love and birth in ancient times. It was linked to goddesses like Aphrodite and Venus. By the 300s, Christians used the scallop to symbolize rebirth through baptism. It also became linked to pilgrimages.

Tests showed the pendant was made from a gold alloy. Only 37% was gold. The rest was silver and some copper. The gold likely came from melted-down coins of the Merovingian dynasty from Francia. This shows the trade and cultural links between Anglo-Saxon England and Europe.

Another grave nearby also had jewellery. It included a gold pendant, silver brooch, and glass beads. The person in this grave might have been close to the "Saxon Princess." Perhaps a relative or a lady-in-waiting buried with her mistress.

Keeping and Displaying the Finds

The discovery was announced on November 20, 2007. Some finds were shown to the press at Kirkleatham Museum near Redcar. Ashok Kumar, the local Member of Parliament, wanted the items to stay in Redcar and Cleveland. He said it was important for local people and schoolchildren to see them. The Culture Minister, Margaret Hodge, agreed that the British Museum would not object to Kirkleatham getting the finds.

A coroner's inquest in 2008 declared the finds "treasure trove". This means experts decide the market value. Half goes to the finder, half to the landowner. But the landowner at Street House gave up his share. He wanted a local museum to buy the items. The Heritage Lottery Fund gave Kirkleatham Museum a grant of £274,000. This money helped buy the finds and create a new Anglo-Saxon gallery.

The museum bought the finds in April 2009. Specialists at Durham University and York Archaeological Trust worked to preserve them. An expert in old woodwork, Richard Darrah, and blacksmith Hector Cole made a replica of the bed. They used tools from the Anglo-Saxon period. A short film about the princess was made at Bede's World in Jarrow.

Before the exhibition opened at Kirkleatham, the finds were shown for five days in May 2011 at Loftus Town Hall. Nearly 1,700 people came to see them. The exhibition at Kirkleatham has been very popular. By October 2011, over 28,000 visitors had seen it in just four months. In April 2012, the museum won the Renaissance Museum title at the Journal and Arts Council Awards.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |