Magic in Anglo-Saxon England facts for kids

Magic in Anglo-Saxon England (called galdorcræft in Old English) is about how people in Anglo-Saxon England believed in and used magic. This was between the 400s and 1000s AD.

People used magic for many things back then. It was mostly for healing sicknesses and making amulets (lucky charms). But sometimes, they also used it to curse others.

During the Anglo-Saxon period, there were two main religions. First, there was Anglo-Saxon paganism, which believed in many gods. Later, Anglo-Saxon Christianity became popular, which believed in one God. Both religions influenced how magic was practiced.

Most of what we know about Anglo-Saxon magic comes from old medical books. These include Bald's Leechbook and the Lacnunga. All these books were written after Christianity arrived.

Written records show that doctors and healers often used magic. Archaeologists have also found evidence that some women were professional magic users, sometimes called cunning women. Anglo-Saxons also believed in witches. These were people who used bad magic to harm others.

Christian missionaries started coming to Anglo-Saxon England in the late 500s. It took many centuries for Christianity to spread. From the 600s onwards, Christian writers spoke out against harmful magic. They called it witchcraft, especially if it used pagan gods. Laws were even made to make witchcraft illegal in Christian kingdoms.

Contents

Anglo-Saxon England: A New Era

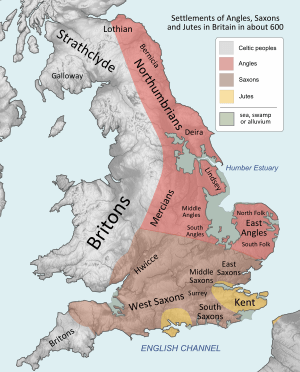

The Roman Empire left southern Britain in the early 400s AD. After this, a new period began, called the Anglo-Saxon period. People in southern and eastern England started to adopt the language, customs, and beliefs of tribes like the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. These tribes came from areas that are now Denmark and northern Germany.

Many historians think this happened because these tribes moved to Britain. But some also suggest that native Britons copied these tribes' culture. Either way, the Anglo-Saxon people in England changed many parts of their lives.

They started speaking Old English, a Germanic language. This was very different from the Celtic and Latin languages spoken before. They also seemed to stop following Christianity, which worships one God. Instead, they began following Anglo-Saxon paganism, which worshipped many gods.

Daily life also changed. People stopped living in roundhouses. They started building rectangular wooden homes, like those in Denmark and northern Germany. Art also changed, with jewelry showing influences from continental Europe.

Pagan and Christian Beliefs

Understanding the Anglo-Saxon gods helps us understand their magic. Anglo-Saxon paganism was a mix of popular beliefs. These traditions were passed down by speaking, not writing.

Words for Magic

The Anglo-Saxons spoke Old English. This language had several words for powerful women. These women were linked to telling the future, protecting people, healing, and cursing. Some words were hægtesse or hægtis, and burgrune.

Another Old English word for magicians was dry. They practiced drycræft. Some experts think this word might come from the Irish word drai. This word referred to druids, who were seen as anti-Christian sorcerers in Irish stories. If so, it was a word borrowed from Celtic languages.

Learning About Anglo-Saxon Magic

Much information about Anglo-Saxon magic has been lost over time. What we do know comes from a few old historical and archaeological sources. These sources have managed to survive until today.

Old Medical Books

The main sources for understanding magic in Anglo-Saxon times are old medical books. Most of these books are from the 1000s. Some are in Old English, and some are in Latin. They are a mix of new writings and copies of older works.

Three main books have survived: Bald's Leechbook, the Lacnunga, and the Old English Herbarium. There are also a few smaller examples.

Historian Stephen Pollington noted that only a small part of Anglo-Saxon medical knowledge was written down. Not everyone could write, and many records have been lost or destroyed over a thousand years.

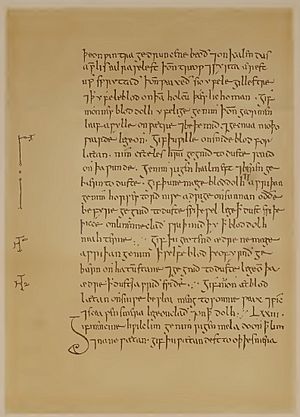

Bald's Leechbook was written around the mid-900s. It has three separate books. It was copied at a writing center in Winchester. This center was started by King Alfred the Great (848/849–899). The first two books combine medical knowledge from the Mediterranean and England. The third book is the only surviving early English medical textbook.

This third book lists remedies for different body parts. Plants are described using their Old English names, not Latin. This suggests it was written before later Christian influences. This part of the Leechbook has more magical instructions. It includes longer, more complex charms and more folklore.

The Lacnunga is another medical book. It starts with an Old English translation of the Herbarium Apulei. This book describes plants and herbs found across Europe. The person who put the Lacnunga together started with recipes for headaches, eye pains, and coughs. But they also added anything else that interested them, making the book a bit mixed up.

The name "Lacnunga" was given to the book by Reverend Oswald Cockayne. He first published it in modern English in 1866.

Burial Sites

Archaeologists have found signs of magical practices in various Anglo-Saxon burial sites. These findings help us understand how magic was part of their lives.

How Magic Was Done

Experts believe that Anglo-Saxon magic involved specific rituals. People thought that performing these steps correctly would make the magic work.

Spirits and Sickness

Many Anglo-Saxon charms show a belief in animism. This means they thought spirits lived in everything. They believed that good or evil spirits could cause things to happen.

The main spirit creature in Anglo-Saxon charms is the ælf (plural ylfe), or elf. Elves were believed to cause sickness in people. Another spirit, a demonic one, was the dweorg or dwerg, which means dwarf. Dwarfs were seen as "disease-spirits" that caused physical harm.

Some charms suggest that bad "disease-spirits" were causing sickness by being in a person's blood. These charms offered ways to remove these spirits. They sometimes called for blood to be drawn out to get rid of the spirit.

When Christianity arrived, some of these old mythical creatures were seen as devils. These devils are also mentioned in the surviving charms. For example, the Leechbook says:

- Against one possessed by a devil: Put in holy water and in ale bishopwort, water-agrimony, agrimony, alexander, cockle; give him to drink.

Magic Spells (Charms)

Experts believe these charm formulas are some of the oldest writings from Anglo-Saxon and Germanic people. They are part of very old traditions.

Comparing Things in Charms

Many Anglo-Saxon charms use comparisons. They link a known event to the magic being performed. The idea was that if two things were linked, what happened to one would happen to the other.

The magician hoped to make things similar by comparing them. This connection might be based on similar sounds, meanings, shapes, or colors. For example, one charm curses someone by comparing their fate to other events:

- May you be consumed as coal upon the hearth,

- may you shrink as dung upon a wall,

- and may you dry up as water in a pail.

- May you become as small as a linseed grain,

- and much smaller than the hipbone of an itchmite,

- and may you become so small that you become nothing.

Other charms compare the magic to events from the Bible. For instance, one charm says:

- Bethlehem is the name of the town where Christ was born.

- It is well known throughout the world.

- So may this act [a theft] become known among men.

Magic and Religion

In Anglo-Saxon times, magic and religion were closely connected. The main religion in England changed over time. From the 400s to the 700s, Anglo-Saxon paganism was common. After that, Anglo-Saxon Christianity became dominant.

Pagan Beliefs and Magic

Anglo-Saxon paganism believed in many gods. They also seemed to respect local gods and spirits. Nature and specific natural places were also important to them. We don't have much evidence to know exactly how they saw the link between magic and their gods. However, some experts think that gods were also affected by magic, just like humans.

The god Woden is the only pre-Christian god mentioned in surviving Anglo-Saxon charms. One charm, called the Nine Herbs Charm, talks about nine different herbs used for medicine. In this charm, it says:

- A worm came crawling, it killed nothing.

- For Woden took nine glory twigs,

- he smote then the adder that it flew apart into nine parts.

This charm uses Woden's victory over the adder to show how the charm can get rid of poison in a person's body. Animal symbols were also important in Anglo-Saxon magic. They were used to protect against evil magic users. These charms used symbols like the Boar, Eagle, and Wolf, which came from pagan beliefs.

Christianity and Magic

Many beliefs in charms and the supernatural continued even after Christianity arrived. They became part of popular religion. This "Cultural Paganism" was not always seen as being against Christian beliefs. Charms continued to be used. They often included animal symbols like the Wolf, Raven, or Boar. These were clearly influenced by the sacred animals of Anglo-Saxon Paganism. These charms were often used to guard against elves and other supernatural creatures. People believed these creatures had bad intentions and could use hostile magic.

People Who Practiced Magic

There were different kinds of magic users in the Anglo-Saxon world.

Leeches (Healers)

Old medical books tell us that some Anglo-Saxon doctors, called leeches, also performed magic. The word "leech" for a healer comes from the Old English word læce. This word meant any kind of healer in Early Mediaeval England. It's not related to the bloodsucking worms. The word læce was common in Old English. It's even part of some place names in England, like Lesbury (meaning "leech-fort") and Lexham (meaning "leech-settlement").

Written records only mention male leeches. There's no mention of female healers in this role. However, this might just mean the records focused on official, paid male doctors. It doesn't mean there were no local village healers or midwives who were women.

Cunning Women

Some archaeologists, like Audrey Meaney and Tania Dickinson, believe there were "cunning women" in the Anglo-Saxon period. These were female magic users.

Witchcraft

Records of Witchcraft

We find evidence of witchcraft, or harmful magic, in written records from the later Anglo-Saxon centuries. The earliest records are Latin "penitentials." These were handbooks for Christian priests. They explained what kind of punishment was needed for each sin, including witchcraft.

One of the earliest was the Paenitentiale Theodori. This book is linked to Theodore of Tarsus, who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 667 to 690. In one section, it talks about "Concerning the worship of idols."

Archaeologist Audrey Meaney noted that this section was similar to an older text. However, the punishment for witchcraft was much lighter in this book. It also specifically mentioned women as witches. This part of the Paenitentiale Theodori was also quoted in other English religious books.

Laws Against Witchcraft

In the introduction to Alfred's Laws, which included Bible judgments, there was a change to the law "Do not allow sorcerers to live." This change said: "Do not allow the women who are accustomed to receive enchanters, magicians and witches to live." Audrey Meaney thought this might have been influenced by the anti-witchcraft parts of the Paenitentiale Theodori.

Witches in Society

In the records we have, Anglo-Saxon witches were usually shown as young women. They practiced magic to find a lover, win their husband's love, have a healthy baby, or protect their children. This is different from the later English idea of a witch, who was usually an old woman. All the records about Anglo-Saxon witchcraft were written by men. This might explain why women were usually the ones accused of witchcraft.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |