Gregorian mission facts for kids

The Gregorian mission was a special Christian journey sent by Pope Gregory the Great in the year 596. Its main goal was to teach Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons in Britain. The leader of this mission was a monk named Augustine of Canterbury.

By the time the last missionary died in 653, the mission had successfully brought Christianity to the southern Anglo-Saxons. This mission, along with others from Ireland and the Franks, helped convert Anglo-Saxons in other parts of Britain too. It even influenced Irish and Scottish missions to mainland Europe.

When the Roman Empire pulled its soldiers out of Britain in 410, some parts of the island were already settled by pagan Germanic tribes. These tribes, later called Anglo-Saxons, took control of areas like Kent. In the late 500s, Pope Gregory sent missionaries to Kent. He wanted them to convert King Æthelberht, whose wife, Bertha of Kent, was a Christian princess from Francia.

Augustine was a leader at Gregory's own monastery in Rome. Gregory helped the mission by asking Frankish rulers along Augustine's path for their support. In 597, the forty missionaries arrived in Kent. King Æthelberht allowed them to preach freely in his capital city, Canterbury.

Soon, the missionaries wrote to Gregory about their success and how many people were converting. We don't know the exact date King Æthelberht became Christian, but it was before 601. A second group of monks and clergy arrived in 601, bringing books and other important items for the new church. Gregory wanted Augustine to be the main archbishop for southern Britain. He also gave Augustine authority over the local British clergy. However, the long-established Celtic bishops refused to accept Augustine's authority.

Before King Æthelberht died in 616, several other church areas, called bishoprics, were set up. After his death, some people turned back to pagan ways. The bishopric of London was even abandoned. King Æthelberht's daughter, Æthelburg, married Edwin, the king of Northumbria. By 627, Paulinus, the bishop who went north with her, had converted Edwin and many other Northumbrians.

When Edwin died around 633, his wife and Paulinus had to flee back to Kent. Even though the missionaries couldn't stay in all the places they had visited, by 653, they had firmly established Christianity in Kent and the nearby areas. They also brought a Roman way of practicing Christianity to Britain.

Contents

Why the Mission Started

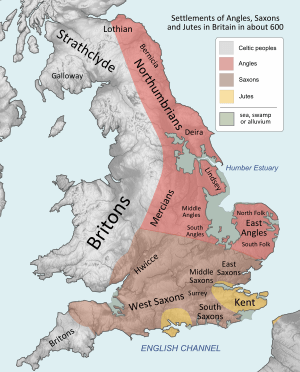

By the 300s, the Roman province of Britannia (which is now Great Britain) had become Christian. Britain even sent three bishops to a church meeting in 314. After the Roman soldiers left Britain in 410, the people were left to defend themselves. Non-Christian tribes like the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, often called Anglo-Saxons, settled in the southern parts of the island.

Most of Britain remained Christian, but being cut off from Rome led to some different practices. This was called Celtic Christianity. For example, they focused more on monasteries than on bishoprics. They also calculated the date of Easter differently and had a different haircut for priests. There is no clear sign that these native Christians tried to convert the new Anglo-Saxon settlers.

The Anglo-Saxon invasions led to the disappearance of most Roman ways of life in the areas they controlled. This included their economic and religious systems. When Augustine arrived in 597, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had little connection to the earlier Roman civilization. The historian John Blair said that Augustine "began his mission with an almost clean slate."

Who Wrote About It?

Most of what we know about the Gregorian mission comes from a medieval writer named Bede. He was an 8th-century monk who wrote a book called Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, or Ecclesiastical History of the English People. For this book, Bede got help and information from many people. This included the abbot at Canterbury and a future Archbishop of Canterbury, Nothhelm. Nothhelm sent Bede copies of letters and documents from Rome.

Other information comes from biographies of Pope Gregory. One was written in northern England around 700. Another was written by a Roman writer in the 800s. Gregory himself also wrote many letters. More than 850 of his letters still exist today. These letters help us understand the mission.

Bede wrote about the native British church as being wicked and sinful. He said they were conquered by the Anglo-Saxons because of this. He also criticized them for not trying to convert the invaders. He also said they resisted the authority of the Roman church. This might mean he didn't fully show the British missionary efforts. Bede was from northern England, so his writings might focus more on events near his home.

Pope Gregory and His Reasons

The Situation Before the Mission

In 595, Pope Gregory I decided to send a mission to the Anglo-Saxons. At that time, Æthelberht ruled the Kingdom of Kent. He had married a Christian princess named Bertha of Kent before 588. Bertha was the daughter of Charibert I, a king of the Franks. As part of her marriage, she brought a bishop named Liudhard with her to Kent. He was her chaplain. They restored an old Roman church in Canterbury, which might be St Martin's Church today.

King Æthelberht was pagan, but he let his wife practice her Christian faith freely. Liudhard doesn't seem to have converted many Anglo-Saxons. Some historians believe that King Æthelberht, influenced by his wife, asked Pope Gregory to send missionaries.

Why Did Gregory Send the Mission?

Most historians believe Gregory started the mission, but the exact reasons are not fully clear. A famous story, told by Bede, says that Gregory saw fair-haired Anglo-Saxon slaves in a Roman market. This inspired him to try and convert their people. The story says Gregory asked who they were. He was told they were Angles from Great Britain. Gregory supposedly replied that they were not Angles, but Angels. The earliest version of this story is from a book about Gregory written around 705.

Bede also wrote that Gregory himself had tried to go on a mission to Britain before he became pope. In 595, Gregory wrote to one of his managers in southern Gaul. He asked him to buy English slave boys so they could be educated in monasteries. Some historians think this means Gregory was already planning the mission to Britain. He might have wanted to send these slaves as missionaries.

One idea is that Gregory believed the end of the world was coming soon. He thought he was meant to play a big part in God's plan for the future. He believed the world would go through six ages, and he was living at the end of the sixth. This idea might have influenced his decision to send the mission. Gregory didn't just focus on Britain. He also supported other missionary efforts. He encouraged bishops and kings to work together to convert non-Christians in their lands.

Some scholars think Gregory's main reason was to increase the number of Christians. Others wonder if political reasons were also involved. For example, he might have wanted to extend the Pope's authority to new areas. He might also have wanted to gain new Christians who would look to Rome for leadership. Influencing the rising power of the Kentish Kingdom under King Æthelberht could have been a factor. Britain was the only part of the old Roman Empire that was still pagan.

Practical Choices

Kent and King Æthelberht were likely chosen for several reasons. King Æthelberht allowed his Christian wife to worship freely. Also, trade between the Franks and Kent was strong. The language difference was not a big problem, as interpreters came from the Franks. Another reason was the growing power of the Kentish kingdom. King Æthelberht was the most powerful Anglo-Saxon ruler in the south.

Finally, Kent's closeness to the Franks allowed for support from a Christian area. Gregory's letters to Frankish kings show that some Franks felt they had a claim to rule over some southern British kingdoms. Having a Frankish bishop like Liudhard could have supported these claims.

Getting Ready

In 595, Gregory chose Augustine, a leader at his own monastery in Rome, to lead the mission to Kent. Gregory chose monks to go with Augustine. He also asked for support from the Frankish kings. The Pope wrote to several Frankish bishops. He introduced the mission and asked them to welcome Augustine and his companions.

Gregory asked kings Theuderic II and Theudebert II, and their grandmother Brunhilda of Austrasia, for help. He also thanked King Chlothar II for his help. Besides offering hospitality, the Frankish bishops and kings provided interpreters. They were also asked to let some Frankish priests join the mission. By getting help from the Franks, Gregory made sure Augustine would be welcomed in Kent. King Æthelberht would likely not mistreat a mission supported by his wife's family and people.

Arrival and First Steps

Who Came and When?

The mission included about forty missionaries, some of whom were monks. Soon after leaving Rome, the missionaries stopped. They felt overwhelmed by the huge task ahead. They sent Augustine back to Rome to ask if they could return. Gregory refused. Instead, he sent Augustine back with letters to encourage the missionaries to keep going. Another reason for the stop might have been news of King Childebert II's death. He was expected to help the missionaries. Augustine might have returned to get new instructions and letters.

In 597, the mission landed in Kent. They quickly had some early success. King Æthelberht allowed the missionaries to live and preach in Canterbury, his capital. They used the church of St. Martin's for their services. This church became the main church for the bishop. Neither Bede nor Gregory mentions the exact date of King Æthelberht's conversion, but it was probably in 597.

How People Converted

In the early medieval period, large-scale conversions often happened after the ruler converted. Many people converted within a year of the mission arriving in Kent. By 601, Gregory was writing to both King Æthelberht and Queen Bertha. He called the king his son and mentioned his baptism. A later tradition says the king's conversion happened on June 2, 597. There's no other proof for this date, but no reason to doubt it either.

Why King Æthelberht chose to become Christian is not certain. Bede suggests the king converted for religious reasons. However, most modern historians see other reasons behind his choice. Given Kent's close ties with Gaul, it's possible King Æthelberht wanted baptism to improve his relations with the Frankish kingdoms. He might have wanted to align himself with one of the groups fighting for power in Gaul.

Bede's writings suggest that while King Æthelberht encouraged conversion, he could not force his people to become Christians. This might have been because many pagans were still in the kingdom. The king had to rely on royal support and friendship to encourage conversions. When someone converted, the king would "rejoice at their conversion" and "hold believers in greater affection."

Instructions from Rome

After these conversions, Augustine sent Laurence back to Rome. He sent a report of his success and asked questions about the mission. Bede recorded this letter and Gregory's replies. Augustine asked Gregory for advice on several things. These included how to organize the church, how to punish church robbers, and who was allowed to marry whom. He also asked about the consecration of bishops. Other topics were relations between the churches in Britain and Gaul, childbirth and baptism, and when people could receive communion.

According to Bede, more missionaries were sent from Rome in 601. They brought a special cloth called a pallium for Augustine. This cloth was a symbol of his status as a metropolitan archbishop. It showed that Augustine was connected to the Pope in Rome. They also brought sacred vessels, robes, relics, and books. With the pallium, a letter from Gregory told the new archbishop to appoint twelve other bishops as soon as possible. He was also to send a bishop to York.

Gregory's plan was to have two main archbishoprics: one at York and one at London. Each would have twelve bishops under them. Augustine was also told to move his main church from Canterbury to London. This never happened. Perhaps it was because London was not part of King Æthelberht's kingdom. Also, London remained a strong pagan area. London was part of the Kingdom of Essex at that time. King Æthelberht's nephew, Sæbert of Essex, ruled Essex. He converted to Christianity in 604.

Along with the letter to Augustine, the returning missionaries brought a letter to King Æthelberht. It urged the king to act like the Roman Emperor Constantine I. This meant he should encourage his followers to convert to Christianity. The king was also urged to destroy all pagan shrines. However, Gregory also wrote a different letter to Mellitus in July 601. In this letter, the Pope suggested a different approach for pagan shrines. He said they should be cleaned of idols and used for Christian worship instead of being destroyed.

Building Churches

Bede says that after the mission arrived in Kent and the king converted, they were allowed to restore and rebuild old Roman churches. One of these was Christ Church, Canterbury. It became Augustine's main church, or cathedral.

Soon after arriving, Augustine founded the monastery of Saints Peter and Paul. It was east of the city, just outside the walls, on land given by the king. After Augustine died, it was renamed St Augustine's Abbey. This abbey is often said to be the first Benedictine abbey outside Italy. It is believed that Augustine brought the Rule of St. Benedict to England by founding it. However, there is no proof that the abbey followed the Benedictine Rule when it was founded.

Efforts in the South

Working with British Christians

Gregory had ordered that the native British bishops should be led by Augustine. So, Augustine arranged a meeting with some of the local clergy between 602 and 604. The meeting happened at a tree later called "Augustine's Oak." This was probably near the border of what is now Somerset and Gloucestershire. Augustine argued that the British church should give up any customs that didn't match Roman practices. This included how they calculated the date of Easter. He also urged them to help convert the Anglo-Saxons.

After some talk, the local bishops said they needed to ask their own people before agreeing to Augustine's requests. They then left the meeting. Bede tells a story that a group of native bishops asked an old hermit for advice. The hermit said they should obey Augustine if, at their next meeting, Augustine stood up to greet them. But if Augustine didn't stand up, they should not submit. When Augustine failed to rise to greet the second group of British bishops, Bede says the native bishops refused to submit to Augustine.

Bede then says Augustine made a prophecy. He said that because the British church didn't help convert the Anglo-Saxons, the native church would suffer at the hands of the Anglo-Saxons. This prophecy was seen as coming true when Æthelfrith of Northumbria supposedly killed 1200 native monks at the Battle of Chester. Bede uses this story to show how the native clergy refused to work with the Gregorian mission.

One likely reason for the British clergy's refusal was the ongoing conflict between the natives and the Anglo-Saxons. The Anglo-Saxons were still taking over British lands when the mission arrived. The British did not want to preach to the invaders of their country. Also, the invaders saw the natives as second-class citizens. They would not have wanted to listen to any conversion efforts from them. There was also a political side. The missionaries could be seen as agents of the invaders. Because King Æthelberht protected Augustine, submitting to Augustine would have been seen as submitting to King Æthelberht's power. The British bishops would not have wanted to do this.

New Bishoprics and Church Matters

In 604, another bishopric was founded at Rochester. Justus was made bishop there. The king of Essex converted in the same year. This allowed another church area to be set up in London, with Mellitus as bishop. Rædwald, the king of the East Angles, also converted. However, no bishopric was set up in his territory. King Rædwald had converted while visiting King Æthelberht in Kent. But when he returned home, he worshipped both pagan gods and the Christian God.

When Augustine died in 604, Laurence, another missionary, took his place as archbishop.

King Æthelberht also created a set of laws. These laws were probably influenced by the missionaries.

Pagan Reactions

After King Æthelberht died in 616, there was a return to pagan ways. Mellitus was forced to leave London and never came back. Justus was also forced out of Rochester. However, he eventually managed to return after spending some time with Mellitus in Gaul. Bede tells a story that Laurence was getting ready to join Mellitus and Justus in Francia. Then he had a dream where Saint Peter appeared and whipped Laurence. This was a warning for his plans to leave his mission. When Laurence woke up, whip marks had magically appeared on his body. He showed these to the new Kentish king, who quickly converted and called back the exiled bishops.

King Æthelberht was followed in Kent by his son Eadbald. Bede says that after his father's death, Eadbald refused to be baptized. He also married his stepmother, which was forbidden by the Roman Church. Although Bede's story says Laurence's miraculous whipping caused Eadbald's baptism, this ignores the political problems Eadbald faced.

Christianity Spreads to Northumbria

Christianity spread in northern Britain when Edwin of Northumbria married Æthelburg, a daughter of King Æthelberht. Edwin agreed to let her continue to worship as a Christian. He also agreed to let Paulinus of York go with her as a bishop. Paulinus was allowed to preach to the court. By 627, Paulinus had converted Edwin. On Easter, 627, Edwin was baptized. Many others were baptized after the king's conversion.

Paulinus was active not only in Deira, which was Edwin's main area of power, but also in Bernicia and Lindsey. Edwin planned to set up a northern archbishopric at York. This followed Gregory the Great's plan for two main church areas in Britain. Both Edwin and King Eadbald sent requests to Rome for a pallium for Paulinus. It was sent in July 634. Many of the East Angles also converted. Their king, Eorpwald, seems to have become Christian.

After Edwin died in battle in 633 or 634, Paulinus returned to Kent with Edwin's wife and daughter. Only one member of Paulinus's group stayed behind, James the Deacon. After Paulinus left Northumbria, a new king, Oswald, invited missionaries from the Irish monastery of Iona. These missionaries worked to convert the kingdom.

Around the time Edwin died in 633, a member of the East Anglian royal family, Sigeberht, returned to Britain. He had converted while in exile in Francia. He asked Honorius, one of the Gregorian missionaries who was then Archbishop of Canterbury, to send him a bishop. Honorius sent Felix of Burgundy, who was already a bishop. Felix successfully converted the East Angles.

Other Important Points

The Gregorian missionaries focused their efforts in areas where Romans had lived. It's possible that Gregory wanted to bring back a form of Roman civilization to England. He might have modeled the church's organization after the church in Francia at that time.

Another important point is how little the mission was based on monasteries. One monastery was set up in Canterbury, which later became St Augustine's Abbey. But even though Augustine and some missionaries were monks, they don't seem to have lived as monks in Canterbury. Instead, they lived more like regular clergy serving a main church. It seems likely that the church areas set up at Rochester and London were organized in a similar way.

One reason for the mission's success was that it worked by example. Gregory's flexibility and willingness to let the missionaries adjust their services and behavior were also important. Another reason was King Æthelberht's willingness to be baptized by someone who was not Frankish. The king would have been careful about letting the Frankish bishop Liudhard convert him. That might have opened Kent to Frankish claims of power. But being converted by someone sent by the distant Pope in Rome was safer. It also gave him the added prestige of accepting baptism from the main source of the Latin Church.

Legacy of the Mission

The last of Gregory's missionaries, Archbishop Honorius, died on September 30, 653. He was replaced as archbishop by Deusdedit, who was a native Englishman.

Pagan Practices

The missionaries had to move slowly. They couldn't do much about getting rid of pagan practices or destroying temples. There was little fighting or bloodshed during the mission. Paganism was still practiced in Kent until the 630s. It was not declared illegal until 640.

The Gregorian missionaries brought a third way of Christian practice to the British Isles. This joined the Gaulish and Irish-British ways already there. Although it's often suggested that the Gregorian missionaries brought the Rule of Saint Benedict to England, there is no proof. The early archbishops at Canterbury claimed to be in charge of all bishops in the British Isles. However, most other bishops did not accept this claim. The Gregorian missionaries seem to have played no part in converting the West Saxons. They were converted by Birinus, a missionary sent directly by Pope Honorius I. The Gregorian missionaries also didn't have much lasting influence in Northumbria. After Edwin's death, the Northumbrians were converted by missionaries from Iona, not Canterbury.

Papal Connections

An important result of the Gregorian mission was the close relationship it created between the Anglo-Saxon Church and the Roman Church. Although Gregory had planned for the southern archbishopric to be in London, that never happened. A later tradition from 797 says that after Augustine's death, the "wise men" of the Anglo-Saxons met. They decided that the main church should stay in Canterbury, because that's where Augustine had preached.

The idea that an archbishop needed a pallium to use his authority comes from the Gregorian mission. This custom started in Canterbury. From there, it spread to mainland Europe by later Anglo-Saxon missionaries like Willibrord and Saint Boniface. The strong ties between the Anglo-Saxon church and Rome became even stronger later in the 7th century. This was when Theodore of Tarsus was appointed to Canterbury by the Pope.

The mission was part of Gregory's plan to look more towards the Western parts of the old Roman Empire. After Gregory, several popes continued this approach. They kept supporting the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. The missionary efforts of Augustine and his companions, along with those of the Irish-Scottish missionaries, became a model for later Anglo-Saxon missionaries to Germany.

Honoring Saints

Another effect of the mission was the honoring of Pope Gregory the Great. The first book about Gregory's life came from Whitby Abbey in Northumbria. Gregory was not very popular in Rome. It was not until Bede's Ecclesiastical History became known that Gregory was honored there too. In Bede's book, Gregory is the main force behind the Gregorian mission. Augustine and the other missionaries are shown as depending on him for advice and help.

Several missionaries were considered saints. These included Augustine, who became another important figure. The monastery he founded in Canterbury was later dedicated to him. Honorius, Justus, Laurence, Mellitus, Paulinus, and Peter were also considered saints. So was King Æthelberht. Bede said that King Æthelberht continued to protect his people even after death.

Art, Buildings, and Music

A few items in Canterbury are traditionally linked to the mission. These include the 6th-century St Augustine Gospels. This book was made in Italy and is now kept at Cambridge. There is also a record of a beautiful, imported Bible of St Gregory, now lost, at Canterbury in the 7th century.

Augustine built a church at his foundation of Sts Peter and Paul Abbey in Canterbury. This was later renamed St Augustine's Abbey. This church was destroyed after the Norman Conquest to make way for a new abbey church. The mission also set up Augustine's main church in Canterbury, which became Christ Church Priory. This church no longer exists.

The missionaries brought a musical style of chant to Britain. It was similar to the chants used in Rome during the mass. During the 600s and 700s, Canterbury was known for its excellent chanting. It sent singing masters to teach others. One of them, James the Deacon, taught chanting in Northumbria after Paulinus returned to Kent. Bede noted that James was very skilled at singing the chants.

Laws and Documents

Some historians believe that the missionaries' knowledge of Roman law influenced early English kings. These kings then created their own law codes. Bede specifically called King Æthelberht's code a "code of law after the Roman manner." Another influence, also brought by the missionaries, was the Old Testament legal codes.

Creating legal codes was not just about making laws. It was also a way for kings to show their power. It showed that kings were not just warlords but also lawmakers. They could ensure peace and justice in their kingdoms. It has also been suggested that the missionaries helped develop the charter in England. Charters are official documents that grant rights or land. The earliest surviving charters show Roman influences.

|

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |