Celtic art facts for kids

Celtic art is the art made by people called Celts. These are people who spoke Celtic languages in Europe, from ancient times until today. It also includes art from old groups whose language we don't know for sure. But their art looks very similar to that of Celtic language speakers.

Defining Celtic art can be tricky. It covers a huge amount of time, places, and cultures. Some experts think there's a link in art styles in Europe all the way back to the Bronze Age. However, archaeologists usually use "Celtic" for the art of the European Iron Age, starting around 1000 BC. This period lasted until the Roman Empire took over most of these lands.

Art historians often begin talking about "Celtic art" from the La Tène period (roughly 5th to 1st centuries BC). This time is also called Early Celtic art. In Britain, this style continued until about 150 AD.

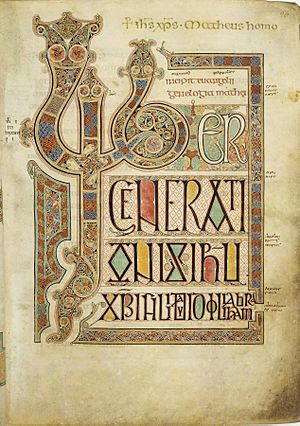

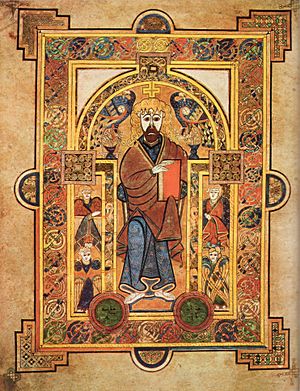

The art from the Early Middle Ages in Britain and Ireland is also very famous. It includes masterpieces like the Book of Kells. This style is known as Insular art. It's the most well-known part of Celtic art from the Early Middle Ages. It also includes the art of the Picts in Scotland.

Both these styles took ideas from other cultures. But they loved geometric patterns more than pictures of people or animals. When people or animals do appear, they are often very stylized. Storytelling scenes usually only show up when outside cultures influenced the art. Energetic circles, triskeles (three-part spirals), and spirals are common features.

Most of the Celtic art we still have is made of precious metals. This might not give us a full picture of all the art that existed. Besides Pictish stones and the tall high crosses of Insular art, large statues are very rare. Some experts think there might have been many wooden statues, like the Warrior of Hirschlanden.

The term "Celtic art" also covers the art of the Celtic Revival. This movement started in the 1700s and continues today. It began when Modern Celts, mostly in the British Isles, wanted to show their identity and nationalism. This style became popular far beyond the Celtic nations. You can still see it today in things like Celtic crosses on graves or interlace tattoos. This revival used designs copied from older Celtic art, especially Insular and Iron Age styles.

Celtic art is usually ornamental. It avoids straight lines and doesn't often use perfect symmetry. It doesn't try to copy nature exactly, like classical art does. It often includes complex symbols. Celtic art has many styles and shows influences from other cultures. You can see this in its knotwork, spirals, key patterns, lettering, animal shapes, plant forms, and human figures.

As archaeologist Catherine Johns said, Celtic art shows "an exquisite sense of balance." Curved shapes are placed so that filled areas and empty spaces work together beautifully. Artists were careful with textures and relief. Very complex curved patterns were designed to fit even the most unusual shapes perfectly.

Contents

Understanding Celtic Art's History

The ancient people we call "Celts" spoke languages that came from a common source. This was called Common Celtic or Proto-Celtic. For a long time, scholars thought this meant these people all came from the same place in southwest Europe. They believed the culture spread through people moving and invading.

Archaeologists found different cultural traits of these people, including art styles. They traced the culture back to the earlier Hallstatt culture and La Tène culture. More recent studies suggest that different Celtic groups don't all share the same ancestors. This means the culture might have spread without large groups of people moving. How "Celtic" language, culture, and genes connected in ancient times is still debated.

The term "Celt" was used in ancient times for the Gauls. Its English form is more modern, appearing around 1607. In the late 1600s, scholars like Edward Lhuyd showed links between Gaulish and the languages spoken in Britain and Ireland. From then on, the term "Celt" was used for people in Britain and Ireland too.

In the 1700s, there was a lot of interest in "primitivism" and the idea of the "noble savage". This led to excitement about all things Celtic and Druidic. The "Irish revival" started after the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. It was a way to show a unique Irish identity. This movement, and similar ones in other countries, later became the "Celtic Revival".

Early Art Before the Celts

[[File:Towriepetrosphere.jpg|thumb|

}}

The earliest culture usually called Celtic is the Hallstatt culture. It comes from the early European Iron Age, around 800–450 BC. But the art from this time, and later, shows a lot of connection with older art from the same areas. This suggests that Celtic culture might have spread more through people adopting new ways, rather than through large groups moving.

Megalithic art around the world uses similar mysterious shapes like circles, spirals, and curves. It's interesting that in Europe, many of these ancient artworks are found in places that are still considered Celtic today. For example, the Neolithic Boyne Valley culture in Ireland left many rock drawings. These are just a few miles from where famous Early Medieval Insular art was made 4,000 years later.

Other connections exist too. For example, the gold lunulas (moon-shaped necklaces) and large collars from the Bronze Age in Ireland and Europe look similar to the torcs worn by Iron Age Celts. All were fancy ornaments worn around the neck. The trumpet-shaped ends of some Bronze Age Irish jewelry also remind us of designs popular in later Celtic art.

Art from the Iron Age

[[File:Stone sculpture of celtic hero.jpg|thumb|A stone head from Mšecké Žehrovice in the Czech Republic, wearing a torc. It's from the late La Tène culture.]] Unlike the rural Iron Age people in modern "Celtic nations," Continental Celtic culture had many large, fortified settlements. The Romans called these "oppidums." The rich leaders of these societies had a lot of wealth. They bought large and expensive items from nearby cultures. Some of these items have been found in graves.

The Hallstatt culture made art with geometric patterns. These patterns used straight lines and rectangles more than curves. The designs were often complex and filled all available space. In this way, they hinted at later Celtic styles.

As Hallstatt society grew richer, it traded with other cultures, especially around the Mediterranean Sea. This brought in objects with very different styles. A famous example is a huge Greek krater (wine-mixing vessel) found in the Vix Grave in France. It was made around 530 BC. Another large Greek vessel found in the Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave has three lions on its rim. One of these was replaced by a Celtic artist who didn't try to copy the Greek style.

Figures of animals and humans do appear, especially in religious art. Some amazing objects are "cult wagons" made of bronze. These are large wheeled carts with many standing figures. They sometimes have a big bowl in the middle, probably for offerings to gods. The figures are simple but often look very impressive. There are also stone figures, often with a "leaf crown" on their heads. This crown might have been a sign of a god.

Human heads alone are much more common. They often appear in relief on many objects. In the La Tène period, faces often appear from patterns that first look like abstract designs or plants. Artists played with faces that changed when viewed from different angles. When a whole body is shown, the head is often very large. This suggests that the human head was very important in Celtic religious beliefs.

The most detailed stone sculptures come from southern France, at Roquepertuse and Entremont. These places were close to areas settled by the Greeks. It's possible that similar wooden sculptures were common. Roquepertuse seems to have been a religious place. Its stonework includes niches where the heads or skulls of enemies might have been placed.

Generally, not many high-quality Celtic art pieces have survived, especially compared to art from Mediterranean cultures of the same time. There's a clear difference between fancy objects for the rich and simpler items used by most people. Many torcs and swords have been found. But the most famous finds, like the Czech head or the Waterloo Helmet, are often unique. We know little about the meaning of the decorations on everyday objects. The purpose of the few objects without a practical use is also unclear.

Hallstatt Art Gallery

The La Tène Style

Around 500 BC, the La Tène style appeared quite suddenly. It's named after a site in Switzerland. This happened at the same time as big changes in society, with major centers moving northwest. Over the next 300 years, the style spread widely to Ireland, Italy, and Hungary. In some places, Celts were fierce raiders. But elsewhere, the spread of Celtic culture might have involved only small movements of people, or none at all.

Early La Tène style took decorative ideas from foreign cultures and made something new. It mixed influences from Scythian art, Greek art, and Etruscan art. The La Tène style is "a very fancy curved art based mainly on classical plant and leaf designs." These include palmettes, vines, tendrils, and lotus flowers, along with spirals and S-shapes.

The most expensive objects, which are often the best preserved, show that classical writers were probably right about Celts. They said Celts were mainly interested in feasting, fighting, and showing off. Society was led by warrior nobles. So, military gear (even ceremonial versions) and drinking containers are among the largest and most impressive finds, besides jewelry.

The torc was clearly a very important symbol of status and was worn widely. Bracelets and armlets were also common. An interesting exception to the lack of human figures and surviving wooden objects are certain water sites. From these, many small carved figures of body parts or whole humans have been found. These are thought to be offerings representing where a person was sick.

Different stages of the La Tène style are recognized. The "early" or "strict" phase kept foreign designs recognizable. This was followed by the "vegetal" style, where patterns were "dominated by continuously moving tendrils."

After about 300 BC, the style split into "plastic" and "sword" styles. The sword style was mostly found on scabbards. The plastic style had designs that stood out in high relief. One expert, Vincent Megaw, even described a "Disney style" of cartoon-like animal heads within the plastic style.

The art of the richest early Continental Celts often used parts of Roman, Greek, and other "foreign" styles. They might have even used foreign artists. But they used these to decorate objects that were clearly Celtic. For example, a torc from the rich Vix Grave has large balls at its ends, like many others. But here, the ends of the ring are shaped like lion paws. This doesn't quite connect logically to the balls. On the outside, two tiny winged horses sit on finely made plaques. It looks impressive but a bit mismatched compared to a British torc from the Snettisham Hoard. That torc, made 400 years later, shows a style that has become more balanced.

The Gundestrup cauldron, from the 1st century BC, is the largest surviving piece of European Iron Age silver. Its designs seem Celtic, but many are not. Its style is much debated. It might have been made in Thrace. To make things more confusing, it was found in a bog in northern Denmark. The Agris Helmet in gold leaf over bronze clearly shows its decorative ideas came from the Mediterranean.

By the 200s BC, Celts began making coins. They copied Greek and later Roman coins. At first, they copied them closely. But gradually, their own style took over. So, sober classical heads on coins grew huge wavy hair, much larger than their faces. Horses became made of a series of strong curved lines.

A unique art form in southern Britain was the mirror. It had a handle and complex engraved decoration on the back of the bronze plate. The front was highly polished to be the mirror. Each of the more than 50 mirrors found has a unique design. The circular shape of the mirror likely led to the complex abstract curved patterns that fill them.

Even though Ireland is important for Early Medieval Celtic art, few La Tène style objects have been found there. However, those found are often of very high quality. The La Tène style didn't appear in Ireland until between 350 and 150 BC. Until the later date, it was mostly found in modern Northern Ireland. After that, Irish art continued to be influenced from outside, even though Ireland was not part of the Roman Empire. This happened through trade and possibly refugees from Britain. It's still unclear if some of the most famous objects from this period were made in Ireland or elsewhere.

In Scotland and western Britain, where the Romans and later Anglo-Saxons were mostly kept out, versions of the La Tène style continued. This style became an important part of the new Insular style. This new style developed to meet the needs of newly Christianized people. In northern England and Scotland, most finds are from after the Roman invasion of the south. However, there are fine Irish finds from the 1st and 2nd centuries. But there's little or no La Tène style art from the 3rd and 4th centuries, a time of trouble in Ireland.

After the Roman conquests, some Celtic elements remained in popular art. This was especially true for Ancient Roman pottery, which Gaul produced a lot of. This pottery mostly followed Italian styles. But it also included local tastes, like figures of gods and pottery painted with animals in very formal styles. Roman Britain made items using Roman shapes, like the fibula, but with La Tène style decoration. Britain also used more enamel than most of the Empire, and on larger objects. Its development of champlevé (a type of enameling) was likely important for later Medieval art in all of Europe. Enamel decoration on penannular brooches, "dragonesque" brooches, and hanging bowls shows a link in Celtic decoration. This link goes from works like the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan to the flourishing of Christian Insular art from the 500s onwards.

- Continental Examples of La Tène Art

- British Examples of La Tène Art

-

The Battersea Shield, England, 350-50 BC. It was for display, not fighting.

-

The Wandsworth Shield-boss, in the "plastic" style.

-

A gold torc, 75 BC, found in the Needwood Forest in the UK.

-

The Waterloo Helmet, a unique find, probably not worn in battle.

Art in the Early Middle Ages

Celtic art in the Middle Ages was made by people in Ireland and parts of Britain. This was during the 700 years from when the Romans left Britain in the 400s, until Romanesque art began in the 1100s. Through the Hiberno-Scottish mission (Irish and Scottish missions), this style influenced art across Northern Europe.

In Ireland, Celtic traditions continued without interruption. The Romans never reached the island. However, Irish objects in La Tène style are very rare from the late Roman period. The 400s to 600s saw a continuation of late Iron Age La Tène art. There were also many signs of Roman and Romano-British influences that had slowly reached Ireland.

When Christianity arrived, Irish art was influenced by both Mediterranean and Germanic traditions. The Germanic influence came from Irish contact with the Anglo-Saxons. This created what is called the Insular or Hiberno-Saxon style. Its golden age was in the 700s and early 800s. Then, Viking raids badly disrupted monastic life. Later in this period, Scandinavian influences were added through the Vikings and mixed Norse-Gael people. Original Celtic work ended with the Norman invasion in 1169–1170. This brought the general European Romanesque style.

In the 600s and 800s, Irish Celtic missionaries traveled to Northumbria in Britain. They brought with them the Irish way of making illuminated manuscripts. This met Anglo-Saxon metalworking skills and designs. In the monasteries of Northumbria, these skills combined. They were probably then sent back to Scotland and Ireland. They also influenced the Anglo-Saxon art of the rest of England. Some of the metal masterpieces created include the Tara Brooch, the Ardagh Chalice, and the Derrynaflan Chalice. New techniques used were filigree (fine wire work) and chip carving. New designs included interlace patterns and animal decorations.

The Book of Durrow is the earliest complete Insular style illuminated Gospel Book. By about 700, with the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Hiberno-Saxon style was fully developed. It had detailed carpet pages that seemed to glow with many colors. This art form reached its peak in the late 700s with the Book of Kells, the most detailed Insular manuscript. Anti-classical Insular art styles were carried to mission centers on the Continent. They had a lasting impact on Carolingian, Romanesque, and Gothic art for the rest of the Middle Ages.

In the 800s and 1000s, plain silver became popular in Anglo-Saxon England. This was likely because more silver was available due to Viking trade and raids. During this time, many beautiful silver penannular brooches were made in Ireland. Around the same time, manuscript making started to decline. While often blamed on the Vikings, this decline began before they arrived. Sculpture began to flourish in the form of the "high cross". These were large stone crosses with carved biblical scenes. This art form reached its peak in the early 900s. Many fine examples remain, like Muiredach's Cross at Monasterboice and the Ahenny High Cross.

The Vikings' impact on Irish art is seen from the late 1000s. Irish metalwork began to copy the Scandinavian Ringerike and Urnes styles. Examples include the Cross of Cong and Shrine of Manchan. These influences were found not just in the Norse center of Dublin, but also in the countryside on stone monuments.

Some Insular manuscripts might have been made in Wales. These include the 8th-century Lichfield Gospels and Hereford Gospels. The late Insular Ricemarch Psalter from the 11th century was definitely written in Wales. It also shows strong Viking influence.

Art from historic Dumnonia (modern Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, and Brittany) is not as well known. These areas later became part of England (and France). However, archaeological studies show a very advanced society. It had strong links with the Byzantine Mediterranean, as well as with the Irish and British in Wales. Many crosses, memorials, and tombstones, like King Doniert's Stone, show evidence of a diverse population. They spoke and wrote in both Brittonic and Latin. They also had some knowledge of Ogham (an ancient alphabet).

Pictish Art in Scotland

From the 400s to the mid-800s, the art of the Picts is mostly known through stone sculptures. There are also some high-quality metalwork pieces. No illuminated manuscripts from the Picts are known. The Picts shared modern Scotland with an area influenced by Irish culture on the west coast, including Iona. To the south was the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. After Christianity arrived, Insular styles greatly influenced Pictish art. Interlace patterns were common in both metalwork and stones.

The heavy silver Whitecleuch Chain has Pictish symbols on its ends. It seems to be like a torc. These symbols are also found on plaques from the Norrie's Law hoard. These are thought to be relatively early pieces. The St Ninian's Isle Treasure includes silver brooches, bowls, and other items. It comes from off the coast of Pictland. It is often seen as mostly Pictish work, showing the best surviving Late Pictish metalwork from about 800 AD.

Pictish stones are divided into three classes by experts. Class I Pictish stones are unshaped standing stones. They have about 35 symbols carved into them. These include abstract designs (like crescent and V-rod, double disc and Z-rod) and carvings of animals (bull, eagle, salmon, adder). They also show objects from daily life (a comb, a mirror). The symbols almost always appear in pairs. About one-third of the time, a mirror, or mirror and comb, symbol is added below the others. This is often thought to represent a woman. These stones are found only in north-east Scotland. Good examples include the Dunnichen and Aberlemno stones.

Class II stones are shaped cross-slabs carved in relief. They have a large cross on one side, or sometimes two. The crosses are richly decorated with interlace, key-patterns, or scrollwork, in the Insular style. On the other side, Pictish symbols appear, often also decorated. They are joined by figures of people (especially horsemen), animals (both real and fantasy), and other scenes. Hunting scenes are common. Biblical scenes are less common. The symbols often seem to 'label' one of the human figures. Scenes of battle or fights between men and fantasy beasts might be from Pictish mythology. Good examples include slabs from Dunfallandy and Meigle.

Class III stones are in the Pictish style but don't have the special symbols. Most are cross-slabs. These stones might be from after the Scottish takeover of the Pictish kingdom in the mid-800s. Examples include the sarcophagus and many cross-slabs at St Andrews.

Many museums have important collections of Pictish stones. These include Meigle, St Vigeans, and St Andrew's Cathedral. Also, the Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh has almost all the major surviving Pictish metalwork.

The Celtic Art Revival

Interest in Celtic visual art came a bit later than interest in Celtic literature. By the 1840s, copies of Celtic brooches and other metalwork became popular. This started in Dublin, then spread to Edinburgh, London, and other countries. The discovery of the Tara Brooch in 1850 boosted this interest. It was shown in London and Paris in the following decades.

The reintroduction of large Celtic crosses for graves and other memorials in the late 1800s has been the most lasting part of the revival. This trend spread far beyond areas with a specific Celtic heritage. Interlace patterns are common on these crosses. Interlace has also been used in architecture, especially in America around 1900. Architects like Louis Sullivan used it, as did Thomas A. O'Shaughnessy for stained glass and wall stenciling. Both were based in Chicago, which has a large Irish-American population. The "plastic style" of early Celtic art influenced the Art Nouveau decorative style. This was very clear in the work of designers like the Manxman Archibald Knox, who worked for Liberty & Co..

The Arts and Crafts Movement in Ireland adopted the Celtic style early on. But they started to move away from it in the 1920s. Some felt that national art should not be limited to old styles. The style had served to show a unique Irish culture. But soon, new ideas led people to see Celtic art as old-fashioned.

Interlace is still seen as a "Celtic" decoration. This is true even though it also has Germanic origins and was important in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian medieval art. It remains a popular design in many forms, especially in Celtic countries, and most of all in Ireland. There, it is still a national style. In recent decades, it has been used worldwide in tattoos. It also appears in fantasy stories with a medieval setting. The Secret of Kells is an animated movie from 2009 about the creation of the Book of Kells. It uses a lot of Insular designs.

By the 1980s, a new Celtic Revival began, and it continues today. This late 20th-century movement is often called the Celtic Renaissance. By the 1990s, more and more artists, craftspeople, designers, and shops specialized in Celtic jewelry and crafts. The Celtic Renaissance has become a worldwide movement, not just limited to the old Celtic countries.

June 9 was named International Day of Celtic Art in 2017. This was done by groups of modern Celtic artists and fans. The day is a chance for exhibits, promotions, workshops, and demonstrations.

Types and Terms in Celtic Art

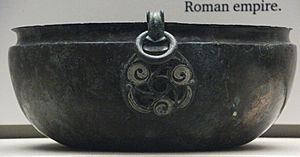

- Hanging bowl: These bowls were traditionally thought to be made by Celtic artists during the Anglo-Saxon conquests of England. They were based on a Roman design, usually made of copper. They had 3 or 4 loops at the top for hanging. Their artistic value comes from the round decorated plaques, often with enamel, found along their rims. Some of the best examples are from the Sutton Hoo treasure (625 AD). The knowledge of how to make them spread to Scotland and Ireland in the 700s. However, it's now debated whether they were actually made in Ireland.

- Carpet page: A page in an illuminated manuscript that is completely covered in decoration. In the Hiberno-Saxon tradition, this was a common feature in Gospel books. One page would introduce each Gospel. They usually had geometric or interlace patterns, often framing a cross in the middle. The oldest known example is from the 7th-century Bobbio Orosius.

- High cross: A tall stone standing cross, usually in the shape of a Celtic cross. The decoration is abstract, often with figures carved in relief. These figures often show crucifixions, but sometimes complex scenes. They are most common in Ireland, but also found in Great Britain and near mission centers on the European continent.

- Pictish stone: A cross-slab, which is a rectangular stone slab with a cross carved in relief on its face. Other pictures and shapes are carved throughout. They are grouped into three Classes, based on when they were made.

- Insular art or the Hiberno-Saxon style: This style existed from the 500s to the 800s. It combined pre-Christian Celtic and Anglo-Saxon metalworking styles. It was used for new religious illuminated manuscripts, as well as sculpture and metalwork for churches and everyday use. It also included influences from post-classical Europe and later Viking decorative styles. The style reached its peak in manuscripts when Irish Celtic missionaries traveled to Northumbria in the 600s and 700s. It produced some of the most amazing Celtic art of the Middle Ages.

- Celtic calendar: The oldest physical Celtic calendar is the broken Gaulish Coligny calendar from the 1st century BC or AD.

See also

In Spanish: Arte celta para niños

In Spanish: Arte celta para niños