Louis Sullivan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis Henry Sullivan

|

|

|---|---|

c. 1895

|

|

| Born | September 3, 1856 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | April 14, 1924 (aged 67) Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Architect |

Louis Henry Sullivan (born September 3, 1856 – died April 14, 1924) was an American architect. Many people call him a "father of skyscrapers" and a "father of modern architecture." He was a very important architect in the Chicago School. He also taught and inspired Frank Lloyd Wright and other architects. Along with Wright, Sullivan is seen as one of the most important American architects. He is famous for the saying "form follows function," which means a building's design should come from its purpose. In 1944, he received a special award for architects, the AIA Gold Medal, after he had passed away.

Contents

Early Life and Training

Louis Sullivan was born in Boston, Massachusetts. His mother was from Switzerland, and his father was from Ireland. Both had moved to the United States in the late 1840s.

Louis was a very smart student. He was able to finish high school early. He also passed tests to skip the first two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He started studying architecture at MIT when he was just sixteen. After one year, he moved to Philadelphia. There, he worked for an architect named Frank Furness.

In 1873, a tough economic time called the Depression of 1873 hit. Frank Furness didn't have much work, so Sullivan lost his job. Sullivan then moved to Chicago in 1873. He wanted to help rebuild the city after the big Great Chicago Fire of 1871. He worked for William LeBaron Jenney, who is known for building one of the first steel frame buildings.

After less than a year, Sullivan went to Paris, France. He studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts for a year. When he returned to Chicago, he worked as a draftsman for another firm. In 1879, a famous architect named Dankmar Adler hired Sullivan. Just one year later, Sullivan became Adler's business partner. This was the start of Sullivan's most successful years.

Building Famous Structures

Adler and Sullivan first became well-known for designing theaters. Most of their theaters were in Chicago. But their fame led to projects in other cities too. One of their biggest projects was the Auditorium Building in Chicago. It opened in 1890. This amazing building had a huge theater, a hotel, and offices. It even had a 17-story tower.

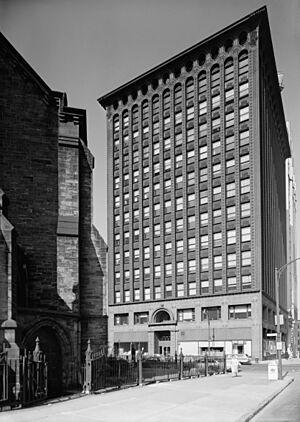

After 1889, their firm became famous for designing office buildings. Some of their notable works include the Wainwright Building in St. Louis (1891). They also designed the Schiller Building (later called the Garrick) in Chicago (1890). Other important buildings are the Chicago Stock Exchange Building (1894). The Guaranty Building in Buffalo, New York (1895–96) is also famous. One of Sullivan's most well-known designs is the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store in Chicago (1899–1904).

How Sullivan Changed Skyscrapers

Before the late 1800s, tall buildings had to have very thick walls at the bottom. These walls supported the entire weight of the building. The taller the building, the thicker the walls needed to be. This limited how high buildings could go.

Then, in the late 1800s, steel became cheap and easy to make. This changed everything for building tall structures. America was growing fast, and cities needed bigger buildings. Steel production made it possible to build skyscrapers in the 1880s. Architects could now create a strong, light skeleton using steel beams. The walls, floors, and windows were then hung from this steel frame. This new way of building, called "column-frame" construction, allowed buildings to go up much higher. It also meant buildings could have much larger windows. This let more sunlight into the rooms. Inside walls could be thinner, which created more space for offices or homes.

Chicago became a testing ground for this new building method. After the 1871 fire, the city needed to rebuild quickly. This led to many new and tall buildings.

The old rules for building tall structures were gone. Architects had new freedom in design. Sullivan used these changes to create a new style for skyscrapers. He designed them with a clear base, a tall middle section (shaft), and a top (cornice). He moved away from old styles and used his own detailed floral designs. These designs often went up the building to make it look even taller. He also made sure the building's shape fit its purpose. This was a revolutionary and successful approach.

His idea that "Form follows function" became a key rule for modern architects. Sullivan said this idea came from an ancient Roman architect named Vitruvius. Vitruvius believed a building should be "solid, useful, and beautiful."

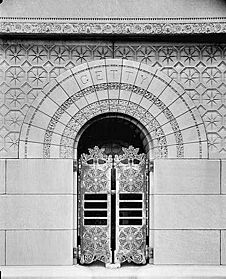

Sullivan's buildings often had smooth, simple main parts. But he loved to add beautiful, detailed decorations. These decorations were often made of iron or terra cotta. Terra cotta is a type of clay that is lighter and easier to work with than stone. His designs included organic shapes like vines and ivy. They also had geometric patterns inspired by his Irish heritage. A famous example is the green ironwork at the entrance of the Carson Pirie Scott store in Chicago.

These unique decorations became Sullivan's signature style. Students of architecture can often recognize his work just by looking at the ornament. Another special part of his work is the large, half-circle arch. He used these arches for entrances, windows, and inside designs.

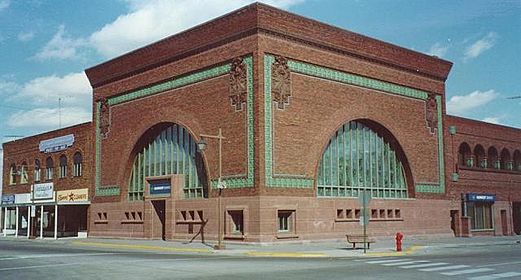

You can see all these elements in Sullivan's famous Guaranty Building in Buffalo, New York. It was finished in 1895. This office building has three main parts: a wide base for shops, a tall middle section with vertical lines to show its height, and a decorated top with round windows. The top is covered with Sullivan's famous Art Nouveau vines. Each entrance has a half-circle arch.

Because of his amazing designs and new building methods, Sullivan is often called the "father" of the American skyscraper. Many other architects were also building skyscrapers at the time. But Sullivan's unique style and ideas made a lasting impact.

Later Years and Challenges

In 1890, Sullivan was one of ten architects chosen to design a major building for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. His large Transportation Building and its huge "Golden Door" stood out. It was the only building not in the popular Beaux-Arts style. It was also the only multicolored building at the fair. Sullivan felt that the fair made American architecture go backward. However, his building was the only one to receive awards from outside America.

Like many American architects, Adler and Sullivan faced problems when the Panic of 1893 (a financial crisis) began. Their business slowed down a lot. In 1894, Adler and Sullivan ended their partnership. The Guaranty Building was their last big project together.

After the partnership ended, Sullivan received very few large projects. He went through a difficult time for twenty years. He had money problems and few commissions. He designed some small banks in the Midwest. He also wrote books.

Louis Sullivan passed away in a Chicago hotel room on April 14, 1924. He is buried in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. A monument was later placed there in his honor.

His Lasting Impact

Sullivan's legacy is complex. Some people see him as the first modern architect. His designs looked to the future and solved problems that modern architecture would face. However, he loved using ornament, which made his style different from the "International Style" that became popular later.

Sullivan's buildings show how amazing his designs were. You can see the vertical lines on the Wainwright Building. There's also the welcoming Art Nouveau ironwork at the entrance of the Carson Pirie Scott store. The white angels on the Bayard Building in New York City are also special. His style is very unique. If you visit the preserved trading floor of the Chicago Stock Exchange at The Art Institute of Chicago, you can see the powerful ornament he used.

Original drawings and other materials from Sullivan are kept at the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries in the Art Institute of Chicago. They are also at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. Pieces of Sullivan's buildings are also in museums around the world.

Saving His Buildings

After World War II, many of Sullivan's buildings were not popular. Some were even torn down. But in the 1970s, people started to care more about saving these important buildings. Richard Nickel was a strong voice for saving them. He organized protests against tearing down architecturally important buildings. Nickel and others sometimes rescued decorative pieces from buildings that were being demolished. Sadly, Nickel died inside Sullivan's Stock Exchange building when a floor collapsed while he was trying to save some elements.

After Nickel's death, the Richard Nickel Committee was formed in 1972. They worked to finish his book about Adler and Sullivan's projects. The book was published in 2010. It includes all 256 projects by Adler and Sullivan. The many photos and research for the book were given to The Art Institute of Chicago. You can see over 1,300 photos on their website.

Another person who helped save Sullivan's buildings was architect Crombie Taylor. He led the effort to save the Van Allen Building in Clinton, Iowa. He moved his family to Iowa to help save the building. He successfully created a non-profit group to protect it.

Jack Randall also worked to save Sullivan's buildings. He helped save the Wainwright Building in St. Louis. He also moved his family to Buffalo, New York, to save Sullivan's Guaranty Building and Frank Lloyd Wright's Darwin Martin House. His efforts were successful in both cities.

A collection of Sullivan's architectural decorations is on display at Lovejoy Library at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. The St. Louis Art Museum and the City Museum in St. Louis also have large collections of his ornaments. This includes a huge cornice from the demolished Chicago Stock Exchange.

The Guaranty Building Interpretive Center in Buffalo opened in 2017. It is on the first floor of the building. This center is the only museum dedicated to Louis Sullivan. It is open to the public and features a model of the building.

Selected Projects

Buildings 1887–1895 by Adler & Sullivan:

- Martin Ryerson Tomb, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago (1887)

- Auditorium Building, Chicago (1889)

- Carrie Eliza Getty Tomb, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago (1890)

- Wainwright Building, St. Louis (1890)

- Charlotte Dickson Wainwright Tomb, Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis (1892). This tomb is considered a major architectural success.

- Union Trust Building (now 705 Olive), St. Louis (1893; street-level ornament changed in 1924)

- Guaranty Building (formerly Prudential Building), Buffalo (1894)

Buildings 1887–1922 by Louis Sullivan:

- Springer Block (later Bay State Building and Burnham Building) and Kranz Buildings, Chicago (1885–1887)

- Selz, Schwab & Company Factory, Chicago (1886–1887)

- Hebrew Manual Training School, Chicago (1889–1890)

- James H. Walker Warehouse & Company Store, Chicago (1886–1889)

- Warehouse for E. W. Blatchford, Chicago (1889)

- James Charnley House (also known as the Charnley–Persky House Museum Foundation), Chicago (1891–1892)

- Albert Sullivan Residence, Chicago (1891–1892)

- McVicker's Theater, second remodeling, Chicago (1890–1891)

- Bayard Building, (now Bayard-Condict Building), New York City (1898). This is Sullivan's only building in New York.

- Commercial Loft of Gage Brothers & Company, Chicago (1898–1900)

- Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Cathedral and Rectory, Chicago (1900–1903)

- Carson Pirie Scott store, Chicago (1899–1904)

- Virginia Hall of Tusculum College, Greeneville, Tennessee (1901)

- Van Allen Building, Clinton, Iowa (1914)

- St. Paul United Methodist Church, Cedar Rapids, Iowa (1910)

- Krause Music Store, Chicago (final commission 1922; front façade only)

Bank Buildings

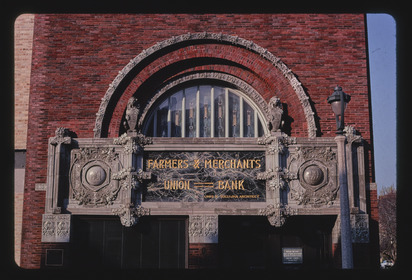

In his later career, Sullivan mostly designed small bank and commercial buildings in the Midwest. These buildings are often called Sullivan's "Jewel Boxes" because of their beautiful design. All of them are still standing today.

- National Farmer's Bank, Owatonna, Minnesota (1908)

- Peoples Savings Bank, Cedar Rapids, Iowa (1912)

- Henry Adams Building, Algona, Iowa (1913)

- Merchants' National Bank, Grinnell, Iowa (1914)

- Home Building Association Company, Newark, Ohio (1914)

- Purdue State Bank, West Lafayette, Indiana (1914)

- People's Federal Savings and Loan Association, Sidney, Ohio (1918)

- Farmers and Merchants Bank, Columbus, Wisconsin (1919)

- First National Bank, Manistique, Michigan (1919–1920), a remodeling of an existing bank building

Buildings That Are No Longer Standing

- Grand Opera House, Chicago, 1880, torn down 1927

- Washington Elementary School, Marengo, Illinois, Adler & Sullivan, torn down 1993

- Pueblo Opera House, Pueblo, Colorado, 1890, destroyed by fire 1922

- New Orleans Union Station, 1892, torn down 1954

- Dooly Block, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1891, torn down 1965

- Chicago Stock Exchange Building, Adler & Sullivan, 1893, torn down 1972. The trading room from this building was saved and rebuilt at the Art Institute of Chicago.

- Zion Temple, Chicago, 1884, torn down 1954

- Troescher Building, Chicago, 1884, torn down 1978

- Transportation Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1893–94, built only for the fair

- Louis Sullivan and Charnley Cottages, Ocean Springs, Mississippi, destroyed by Hurricane Katrina

- Schiller Building (later Garrick Theater), Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1891, torn down 1961

- Third McVickers Theater, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1883, torn down 1922

- Thirty-Ninth Street Passenger Station, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1886, torn down 1934

- Standard Club, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1887–88, torn down 1931

- Pilgrim Baptist Church, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1891, destroyed by fire January 6, 2006

- Wirt Dexter Building, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1887, destroyed by fire October 24, 2006

- George Harvey House, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1888 destroyed by fire November 4, 2006

Gallery

-

Chicago Stock Exchange Building

-

Gage Building (on right)

-

Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Cathedral, exterior

-

Harold C. Bradley House, Wisconsin

See also

In Spanish: Louis Sullivan para niños

In Spanish: Louis Sullivan para niños

- American Prize for Architecture

- Richard Bock

- Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |