Long Depression facts for kids

The Long Depression was a big economic slowdown that affected many countries around the world. It started in 1873 and lasted for a long time, either until 1879 or even 1896, depending on how you measure it. This period was especially tough in Europe and the United States. These places had been growing fast thanks to the Second Industrial Revolution after the American Civil War.

At the time, people called this period the "Great Depression." But later, when the Great Depression of the 1930s happened, this earlier one got a new name: the "Long Depression." Even though prices generally fell and the economy slowed down, it wasn't as severe as the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The United Kingdom was hit hardest. It lost some of its strong industrial lead over other European countries during this time. Many people thought the British economy was in a continuous slump from 1873 to 1896. Some even called it the Great Depression of 1873–1896. This was due to financial and factory losses, plus a long slowdown in farming.

In the United States, historians call it the Depression of 1873–1879. It began with the Panic of 1873 and ended before another slowdown, the Panic of 1893. The U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research says this economic slowdown lasted from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it was the longest slowdown they've recorded, even longer than the Great Depression of the 1930s. During this time, 18,000 businesses went bankrupt in the U.S., including 89 railroads. Unemployment reached its highest point in 1878, with 8.25% of people out of work.

Contents

What Caused the Long Depression?

The years before the depression saw big military conflicts and a lot of economic growth. In Europe, the Franco-Prussian War ended, creating a new political system in Germany. France had to pay Germany a huge amount of money, about £200 million. This led to a lot of investment and rising prices in Germany and Central Europe. New technologies like the Bessemer converter (for making steel) were being used quickly, and railroads were booming.

In the United States, the American Civil War had ended. After a short slowdown from 1865 to 1867, there was a huge boom in investments. This was especially true for railroads being built on public lands in the Western United States. Most of this expansion was paid for by investors from other countries.

The Panic of 1873

In 1873, the value of silver started to drop. This was made worse when the German Empire stopped making certain silver coins. In April, the U.S. government passed the Coinage Act of 1873. This law basically ended the system where U.S. money was based on both gold and silver (called the bimetallic standard). Instead, the U.S. switched to using only a gold standard.

This change meant there was less money available in the U.S. economy. It also pushed silver prices down even further. New silver mines were opening in Nevada, which encouraged more mining. But this increased the supply of silver just as demand was falling. Silver miners would arrive at U.S. mints, not knowing about the new law, only to find their silver was no longer wanted for coins. By September, the U.S. economy was in trouble. Falling prices caused banks to panic and businesses to stop investing. This all led to the Panic of 1873.

The Panic of 1873 is often called the "first truly international crisis." Optimism had been driving stock prices very high in central Europe. Fears of an economic "bubble" (when prices get too high) led to a panic in Vienna, Austria, in April 1873. The Vienna Stock Exchange crashed on May 8, 1873, and stayed closed for three days. When it reopened, the panic seemed to have calmed down in Austria-Hungary.

However, the financial panic reached the Americas a few months later on September 18, 1873. This happened after the banking company Jay Cooke and Company failed. They had invested heavily in the Northern Pacific Railway. This railway had received a huge amount of public land, about 40 million acres, in the Western United States. Cooke tried to raise $100 million for the company, but he couldn't sell enough bonds. His bank failed, and soon several other major banks followed. The New York Stock Exchange closed for ten days on September 20.

The financial problems then spread back to Europe. This caused a second panic in Vienna and more bank failures in other parts of Europe. France, which had been experiencing falling prices before the crash, and the United Kingdom were not as badly affected at first.

Some people believe the depression started with the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. This war badly hurt the French economy. Under the Treaty of Frankfurt, France had to pay huge war payments to Germany.

The main reason for falling prices in the U.S. was the strict money policy used to return to the gold standard after the Civil War. The U.S. government was taking money out of circulation to reach this goal. This meant there was less money available for trade. This policy caused the price of silver to fall, leading to big losses in asset values. After 1879, production was growing, which also pushed prices down due to more factory output, trade, and competition.

In the U.S., there was a lot of risky financing. This was partly due to "greenbacks," which were paper money printed to pay for the Civil War. There was also a lot of fraud in building the Union Pacific Railway up to 1869, leading to the Crédit Mobilier scandal. Too many railroads were built, and weak markets caused this economic bubble to burst in 1873. Both the Union Pacific and Northern Pacific lines were key to the collapse. Another railroad bubble was the Railway Mania in the United Kingdom.

Because of the Panic of 1873, some governments stopped linking their currencies to a fixed value to save money. The decision by European and North American governments to stop using silver for money in the early 1870s definitely played a part. The U.S. Coinage Act of 1873 was strongly opposed by farmers and miners. They saw silver as more helpful to rural areas than to big city banks. Also, some U.S. citizens wanted the government to keep issuing paper money (called United States Notes). They believed this would prevent falling prices and help exports. Western U.S. states were very angry. Nevada, Colorado, and Idaho were major silver producers with active mines. For a few years, mining slowed down. The government started coining silver dollars again with the Bland–Allison Act of 1878. The U.S. government began buying silver again in 1890 with the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

Some economists believe the 1873 depression was caused by a shortage of gold, which weakened the gold standard. They think that new gold discoveries, like the 1848 California Gold Rush and the 1896–99 Klondike Gold Rush, helped solve such crises. Other studies suggest that big changes from the Second Industrial Revolution caused major shifts in economies. These changes came with costs that might have also helped cause the depression.

How the Depression Unfolded

Like the later Great Depression, the Long Depression affected different countries at different times and rates. Some countries even grew quickly during certain periods. However, globally, the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s saw prices fall and economic growth rates much lower than before and after.

Between 1870 and 1890, iron production in the five biggest producing countries more than doubled. Steel production increased twenty times, and railroad building boomed. But at the same time, prices in several markets crashed. The price of grain in 1894 was only a third of what it was in 1867. The price of cotton fell by almost 50% in just five years, from 1872 to 1877. This caused great hardship for farmers. This collapse led many countries, like France, Germany, and the United States, to protect their own industries. It also caused many people to leave countries like Italy, Spain, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. Similarly, while iron production doubled, the price of iron was cut in half.

Many countries had much lower growth rates compared to earlier in the 19th century and later:

| 1850s–1873 | 1873–1890 | 1890–1913 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.3 | 2.9 | 4.1 | |

| 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | |

| 6.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | |

| 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.5 | |

| 0.9 | 3.0 | ||

| 3.1 | 3.5 |

| 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.5 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 14.4 | 22.9 | 23.2 | 21.1 | |

| 8.5 | 10.3 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 19.7 | |

| 8.2 | 10.4 | 12.5 | 16.0 | 19.6 | 23.5 | 29.4 | |

| 7.2 | 8.3 | 10.3 | 12.7 | 16.6 | 19.9 | 26.4 | |

| 7.2 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 11.3 | 12.2 | 15.3 | |

| 5.5 | 5.9 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.4 |

Impact on Different Countries

The global economic crisis first hit Austria-Hungary. The Vienna Stock Exchange crashed in May 1873. In Hungary, the panic ended a period of intense railroad building.

In the late 1870s, the economy in Chile got worse. Chilean wheat exports couldn't compete with wheat from Canada, Russia, and Argentina. Chilean copper was largely replaced by copper from the United States and Spain. Money from silver mining in Chile also dropped. Some historians believe that Chile's economic problems and the desire for new wealth from nitrates led to the War of the Pacific with Bolivia and Peru. Another response to the crisis was a new push to conquer indigenous lands in Araucanía in the 1880s.

France had a somewhat unusual experience. After losing the Franco-Prussian War, France had to pay £200 million in payments to Germany. The country was already struggling when the 1873 crash happened. France decided to deliberately lower prices while paying off the war payments. The Paris Bourse crash of 1882 sent France into a deeper depression. This one "lasted longer and probably cost France more than any other in the 19th century." A French bank, Union Générale, failed in 1882. This caused the French to pull a lot of money from the Bank of England and led to a collapse in French stock prices.

The financial crisis was made worse by diseases affecting France's wine and silk industries. French investment at home and from other countries dropped to the lowest levels in the second half of the 19th century. After a boom in new investment banks after the Franco-Prussian War, the crash badly damaged the French banking industry. This lasted until the early 1900s. French finances were further hurt by failed investments abroad, mainly in railroads and buildings. France's total national income went down over ten years, from 1882 to 1892.

A ten-year "tariff war" (a fight over taxes on imported goods) broke out between France and Italy after 1887. This hurt relations between the two countries. Since France was Italy's biggest investor, French money being pulled out of Italy was especially damaging.

Russia's experience was similar to the U.S. It had three separate slowdowns in manufacturing during this period (1874–1877, 1881–1886, and 1891–1892). These were separated by times of recovery.

The United Kingdom had faced economic crises every decade since the 1820s. It was less affected by this financial crisis at first. Even so, the Bank of England kept interest rates as high as 9% in the 1870s. The 1878 failure of the City of Glasgow Bank in Scotland happened due to a mix of dishonest actions and risky investments in Australian and New Zealand companies (farming and mining) and American railroads.

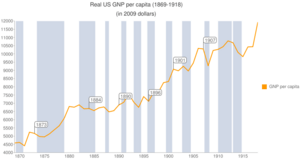

In the United States, the Long Depression started with the Panic of 1873. The National Bureau of Economic Research says the slowdown lasted from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it was the longest slowdown identified by the NBER. This is longer than the Great Depression's 43 months of slowdown. Figures from economists Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz show that the total value of goods and services produced in the U.S. (net national product) increased 3% per year from 1869 to 1879. The actual amount of goods and services grew at 6.8% per year during that time. However, the U.S. population grew by over 17.5% between 1869 and 1879. So, the growth per person was lower. After the slowdown ended in 1879, the U.S. economy remained unstable. It experienced slowdowns for 114 out of 253 months until January 1901.

| Industry | % decline in output |

|---|---|

| Durable goods (items that last a long time) | 30% |

| Iron and steel | 45% |

| Construction | 30% |

| Overall | 10% |

The big drop in prices severely affected wages. In the United States, wages fell by a quarter during the 1870s. In some places, like Pennsylvania, they fell by as much as half. Although actual buying power of wages had grown strongly after the Civil War, they stopped growing until the 1880s. The collapse of cotton prices badly hurt the economy of the southern United States, which was already damaged by the war. Even though farm prices fell sharply, American agriculture continued to produce more.

Thousands of American businesses failed, unable to pay back over a billion dollars in debt. One out of four workers in New York was unemployed in the winter of 1873–1874. Across the country, a million people lost their jobs.

The industries that saw the biggest drops in production were manufacturing, construction, and railroads. Railroads had been a huge source of growth before the crisis. Railroad mileage increased by 50% from 1867 to 1873. After taking up to 20% of U.S. investment before the crash, this expansion stopped dramatically in 1873. Between 1873 and 1878, the total railroad mileage in the U.S. hardly grew at all.

The Freedman's Savings Bank was one of the victims of the financial crisis. It was started in 1865 after the Civil War to help the economic well-being of newly freed African Americans. In the early 1870s, the bank got involved in risky investments, putting money into real estate and unsecured loans to railroads. Its collapse in 1874 was a severe blow to African-Americans.

The economic slowdown caused political problems for President Ulysses S. Grant. Historian Allan Nevins described the end of Grant's presidency as a time of "paralysis and discredit." The President had no clear plans or public support. He had to change his cabinet under intense criticism. Many of his cabinet members were inexperienced or had lost trust. The nation was drifting without clear leadership during a time of deep economic trouble.

Recovery began in 1878. The amount of railroad track laid increased from 2,665 miles in 1878 to 11,568 miles in 1882. Construction started to recover by 1879. The value of building permits increased two and a half times between 1878 and 1883. Unemployment fell to 2.5%, even with high immigration.

Business profits briefly fell between 1882 and 1884. The recovery in railroad construction reversed. The price of steel rails crashed from $71 per ton in 1880 to $20 per ton in 1884. Manufacturing fell again, with durable goods output dropping by another quarter. This decline became a short financial crisis in 1884. Several New York banks collapsed. At the same time, from 1883–1884, tens of millions of dollars of American investments owned by foreigners were sold. This was due to fears that the U.S. was going to abandon the gold standard. This financial panic closed eleven New York banks and over a hundred small state banks. It also led to defaults on at least $32 million worth of debt. Unemployment, which had been 2.5% between slowdowns, jumped to 7.5% in 1884–1885, and 13% in the northeastern U.S. Immigration also dropped because of the worsening job market.

The 1880s saw a huge expansion of industry, railroads, and overall production. The total value of goods and services produced and income per person grew greatly. Even the supposed "money shortage" never happened. The money supply actually increased by 2.7% per year during this time. From 1873 through 1878, the total supply of bank money rose from $1.964 billion to $2.221 billion. This was a rise of 13.1%, or 2.6% per year. So, there was a small but clear increase, not a decrease.

How People Reacted to the Crisis

The time before the Long Depression had seen more economic cooperation between countries. Many efforts, like the Latin Monetary Union, were then stopped or slowed down by the economic problems. The huge drop in farm prices led many nations to adopt "protectionism." This means they put taxes on imported goods to protect their own industries.

After rejecting free trade policies, French president Adolphe Thiers led the new Third Republic towards protectionism. This eventually led to the strict Méline tariff in 1892. Germany's powerful landowners, called Junkers, were hurt by cheap imported grain. They successfully pushed for a protective tariff in 1879 in Otto von Bismarck's Germany, despite protests from his allies. In 1887, Italy and France started a bitter "tariff war." In the United States, Benjamin Harrison won the 1888 US presidential election by promising to protect American industries.

Because of these protectionist policies, the global merchant shipping fleet didn't grow much from 1870 to 1890. It then nearly doubled in size during the economic boom that followed before World War I. Only the United Kingdom and the Netherlands continued to have low tariffs.

Money Policies

In 1874, a year after the 1873 crash, the United States Congress passed a law called the Inflation Bill of 1874. It was meant to deal with falling prices by adding more "greenbacks" (paper money) to the money supply. However, under pressure from businesses, President Ulysses S. Grant stopped the law from passing. In 1878, Congress overrode President Rutherford B. Hayes's veto to pass the Silver Purchase Act. This was a similar but more successful attempt to promote "easy money," meaning more money in circulation.

Strikes and Unrest

The United States experienced its first nationwide strike in 1877, called the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. This led to widespread unrest and often violence in many major cities and industrial centers. These included Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Reading, Saint Louis, Scranton, and Shamokin.

New Imperialism

The Long Depression helped bring back colonialism. This led to the New Imperialism period, known for the "scramble for Africa." Western powers looked for new markets for their extra money and goods. According to Hannah Arendt's book The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), the "unlimited expansion of power" followed the "unlimited expansion of money and resources."

In the United States, starting in 1878, the rebuilding and expansion of western railways happened. This came with the widespread giving away of water, timber, fish, and minerals in what had been Native American territory. This led to the growth of markets and industry, along with powerful railroad owners. This period, known as the Gilded Age, created great wealth for a few. The cycle of boom and bust repeated itself with the Panic of 1893, another huge market crash.

Recovery from the Depression

In the United States, the National Bureau of Economic Analysis says the economic slowdown ended in March 1879. In January 1879, the United States returned to the gold standard, which it had stopped using during the Civil War. According to economist Rendigs Fels, the gold standard stopped prices from falling further. This was also helped by especially good farm production in 1879. The idea that a single slowdown lasted from 1873 to 1896 or 1897 is not supported by most modern studies. Some even suggest the lowest point of this economic cycle might have been as early as 1875.

In fact, from 1869 to 1879, the U.S. economy grew at a rate of 6.8% for the actual value of goods and services produced. The actual value per person grew at 4.5%. Wages, after accounting for price changes, stayed the same from 1869 to 1879. But from 1879 to 1896, wages rose 23%, and prices fell 4.2%.

Why Did It Happen?

Economist Irving Fisher believed that the Panic of 1873 and the severe slowdowns that followed could be explained by debt and falling prices. He thought that a financial panic would cause people to quickly sell off assets to get cash. This selling would cause asset prices to crash and lead to falling prices (deflation). This, in turn, would make financial institutions sell off more assets, only making prices fall further and straining their money reserves. Fisher believed that if governments or private businesses had tried to increase the money supply, the crisis would have been less severe.

David Ames Wells (1890) wrote about the technological advancements during the period of the Long Depression (1870–1890). Wells described the changes in the world economy as it moved into the Second Industrial Revolution. He wrote about changes in trade, like better steam shipping, railroads, the international telegraph network, and the opening of the Suez Canal. Wells gave many examples of how technology improved production in various industries. He also discussed the problems of having too much production capacity and markets being flooded with goods.

Wells' first sentence in his book was: "The economic changes that have occurred during the last quarter of a century—or during the present generation of living men—have unquestionably been more important and more varied than during any period of the world's history."

Other changes Wells mentioned include less need for warehouses and inventories, fewer middlemen, bigger factories producing more cheaply, the decline of skilled craftspeople, and fewer farm workers. About the whole 1870–90 period, Wells said: "Some of these changes have been destructive, and all of them have inevitably occasioned, and for a long time yet will continue to occasion, great disturbances in old methods, and entail losses of capital and changes in occupation on the part of individuals. And yet the world wonders, and commissions of great states inquire, without coming to definite conclusions, why trade and industry in recent years has been universally and abnormally disturbed and depressed."

Wells noted that many government investigations into the "depression of prices" (deflation) found various reasons, such as a shortage of gold and silver. However, Wells showed that the U.S. money supply actually grew during the period of falling prices. Wells also pointed out that falling prices only happened for goods that benefited from improved manufacturing and transportation. Goods made by craftspeople and many services did not decrease in value, and the cost of labor actually increased. Also, falling prices did not happen in countries that didn't have modern manufacturing, transportation, and communication.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman, in his book A Monetary History of the United States, blamed this long economic crisis on the new gold standard. He called part of it by its traditional name, The Crime of 1873. Friedman also pointed to the increase in the gold supply through new mining techniques as a reason for the recovery. This forced switch to a currency whose supply was limited by nature, unable to grow with demand, caused a series of economic slowdowns that affected the entire period of the Long Depression. Murray Rothbard, in his book History of Money and Banking of the United States, argues that the long depression was just a misunderstood slowdown. He says that actual wages and production were increasing throughout the period. Like Friedman, he believes falling prices were due to the U.S. returning to a gold standard after the Civil War, which caused prices to drop.

See also

- Crisis theory

- Economic history

- Equine Influenza of 1872

- Gilded Age

- Great Depression of British Agriculture (1873–1896)

- Kondratiev wave

- List of economic crises

- List of recessions in the United States

- New Imperialism

- Panic of 1873

- Panic of 1893

- Second Industrial Revolution

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |