Hannah Arendt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hannah Arendt

|

|

|---|---|

Arendt in 1933

|

|

| Born |

Johanna Arendt

14 October 1906 Linden, Province of Hanover, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire

|

| Died | 4 December 1975 (aged 69) New York City, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Bard College |

| Other names | Hannah Arendt Bluecher |

| Citizenship |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Heinrich Blücher

(m. 1940; died 1970) |

| Relatives | Max Arendt (grandfather) Henriette Arendt (aunt) |

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Education | University of Berlin University of Marburg University of Freiburg University of Heidelberg (PhD, 1929) |

|

Notable work

|

List

The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

The Human Condition (1958) On Revolution (1963) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

List

|

| Doctoral advisor | Karl Jaspers |

|

Main interests

|

Political theory, totalitarianism, philosophy of history, modernity |

|

Notable ideas

|

List

The banality of evil

Natality |

|

Influenced

|

|

| ,Achille Mbembe | |

| Signature | |

Hannah Arendt (born Johanna Arendt; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a very important political philosopher and writer. She was also a Holocaust survivor. Many people think she was one of the most influential political thinkers of the 20th century.

Hannah was born into a Jewish family in Linden, Germany, in 1906. When she was three, her family moved to Königsberg because her father was ill. He died when she was seven. Hannah grew up in a family that believed in social progress and was not very religious. Her mother was a strong supporter of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. After finishing high school in Berlin, Hannah studied at the University of Marburg. She earned her doctorate degree in philosophy from the University of Heidelberg in 1929. Her main teacher was the philosopher Karl Jaspers. Her special project for her degree was called Love and Saint Augustine.

Hannah Arendt married Günther Stern in 1929. But soon, antisemitism (hatred of Jewish people) grew stronger in Nazi Germany in the 1930s. In 1933, when Adolf Hitler came to power, Hannah was arrested. She was briefly put in prison by the Gestapo for doing secret research about antisemitism. After she was released, she escaped Germany. She lived in Czechoslovakia and Switzerland before settling in Paris, France. There, she helped an organization called Youth Aliyah. This group helped young Jewish people move to Palestine. The German government took away her German citizenship in 1937. She divorced Stern that year and then married Heinrich Blücher in 1940.

When Germany invaded France in 1940, the French government held her as a foreigner. She managed to escape and traveled to the United States in 1941 through Portugal. She made New York City her home for the rest of her life. She became a writer and editor. She also worked for the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction group. She became an American citizen in 1950. Her book The Origins of Totalitarianism was published in 1951. This book made her famous as a deep thinker and writer. She then wrote other important books, including The Human Condition (1958), and Eichmann in Jerusalem and On Revolution (both in 1963).

Hannah taught at many American universities. She passed away suddenly from a heart attack in 1975, at 69 years old. Her last book, The Life of the Mind, was not finished. Her writings cover many topics. She is best known for her ideas about power, evil, politics, and totalitarianism. Many people remember her for the discussions around the Eichmann Trial. She tried to explain how ordinary people could become involved in terrible systems like totalitarianism. She also used the famous phrase "the banality of evil". Hannah Arendt is remembered through special awards, street names, and schools named after her.

Contents

- Early Life and Education (1906–1929)

- Career and Exile

- Personal Relationships

- Final Years and Passing

- Key Works

- Political Ideas

- Love and Saint Augustine (1929)

- The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

- Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess (1957)

- The Human Condition (1958)

- Between Past and Future (1961)

- On Revolution (1963)

- Men in Dark Times (1968)

- Crises of the Republic (1972)

- Hannah Arendt and the Eichmann Trial (1961–1963)

- Views and Legacy

- See also

- Images for kids

Early Life and Education (1906–1929)

Family Background

Hannah Arendt was born as Johanna Arendt in 1906 in Linden, Prussia. Her German Jewish family was well-off, educated, and not very religious. They were merchants from Königsberg. Her grandparents were part of the Reform Jewish community. Her grandfather, Max Arendt, was a well-known businessman and local politician. He was also a leader in the Königsberg Jewish community. He saw himself mostly as German and did not support Zionism (the movement to create a Jewish state).

Hannah was the only child of Paul and Martha Arendt. They married in 1902. Hannah was named after her grandmother. Her mother's family came to Königsberg in 1852. They were refugees escaping antisemitism. They became successful tea importers. Hannah's parents were more educated and had more left-leaning political views than her grandparents. They were Social Democrats. Paul Arendt was an engineer, but he loved Classics. He had a large library that Hannah enjoyed reading from. Martha Cohn was a musician and had studied in Paris.

In the first four years of their marriage, the Arendts lived in Berlin. They supported a socialist newspaper. When Hannah was born, her father worked for an electrical engineering company in Linden. They lived in a house on the market square. In 1909, they moved back to Königsberg because Paul's health was getting worse. He died on October 30, 1913, when Hannah was seven. Her mother then raised her. They lived in her grandfather's house in a Jewish neighborhood. Hannah's parents were not religious, but they allowed her grandfather to take her to the Reform synagogue. She also received religious lessons from the rabbi, Hermann Vogelstein. Her family was friends with many smart and professional people. They had high standards and ideals.

This was a good time for the Jewish community in Königsberg. Hannah's family had fully adopted German culture. She later remembered how serious they were about "assimilation," meaning fitting into the German way of life. Even so, Jewish people did not have full citizenship rights. While not always obvious, antisemitism was present. Hannah later understood her Jewish identity more clearly after facing open antisemitism as an adult. She felt a strong connection to Rahel Varnhagen (1771–1833). Rahel was a Prussian socialite who wanted to be part of German culture but was rejected because she was born Jewish. Hannah later called Rahel "my very closest woman friend, unfortunately dead a hundred years now."

In the last two years of World War I, Hannah's mother led social democratic discussion groups. She became a follower of Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919) as socialist uprisings happened in Germany. Luxemburg's ideas later influenced Hannah's political thinking. In 1920, Martha Cohn married Martin Beerwald. He was a widower with two daughters. They moved to his home, which gave Hannah more social and financial security. Hannah was 14 at the time and gained two older stepsisters, Clara and Eva.

Education

Early Schooling

Hannah Arendt's mother raised her with strict ideas from Goethe. This included reading all of Goethe's works. The main ideas were self-discipline, controlling emotions, and being responsible for others. Hannah's mother carefully wrote down her daughter's progress in a book called Our Child. She compared Hannah's development to what was considered "normal."

Hannah went to kindergarten starting in 1910. Her teachers were impressed by how smart she was. In August 1913, she started at the Szittnich School. But her studies were stopped by World War I. Her family had to flee to Berlin in August 1914 to escape the Russian army. They stayed with her mother's sister, Margarethe Fürst, and her children. Hannah went to a girls' school in Berlin-Charlottenburg. After ten weeks, they returned to Königsberg. They spent the rest of the war years at her grandfather's house.

Hannah continued to be very smart. She learned ancient Greek as a child. She wrote poetry as a teenager. She even started a Greek and philosophy club at her school. She was very independent in her studies and loved to read. She read a lot of French and German literature, poetry, and philosophy. By age 14, she had read works by Kierkegaard, Jaspers, and Kant. Kant, who was also from Königsberg, greatly influenced her thinking. He once wrote that Königsberg was "the right place for gaining knowledge concerning men and the world even without travelling."

Hannah attended the Königin-Luise-Schule for her high school education. Most of her friends at school were gifted children from Jewish professional families. They were usually older than her and went on to university. Among them was Ernst Grumach, who introduced her to Anne Mendelssohn, who became a lifelong friend. When Anne moved away, Ernst became Hannah's first romantic relationship.

University Studies (1922–1929)

Hannah was expelled from her high school in 1922, at age 15. This happened because she led a protest against a teacher who had insulted her. Her mother sent her to Berlin to stay with family friends who were Social Democrats. She lived in a student dorm and took classes at the University of Berlin (1922–1923). She studied classics and Christian theology there. She then passed the entrance exam for the University of Marburg. Her aunt Frieda Arendt, a teacher, and Frieda's husband helped her financially.

At Marburg (1924–1926), she studied classical languages, German literature, Protestant theology, and philosophy. She was very impressed by the young philosopher Martin Heidegger, calling him "the hidden king [who] reigned in the realm of thinking." Heidegger's classes focused on the meaning of "Being." Hannah later described these classes as teaching "passionate thinking."

Hannah felt restless and not fully satisfied with her studies. Her time with Heidegger was a big change for her. He remained one of the most important influences on her ideas. At Marburg, Hannah lived at Lutherstraße 4. Her friends included Hans Jonas and Gunther Siegmund Stern, who later became her first husband.

After a year at Marburg, Hannah spent a semester at Freiburg. She then moved to the University of Heidelberg in 1926. She finished her main project for her doctorate degree in 1929 under Karl Jaspers. Jaspers was a friend of Heidegger and another leading figure in the new Existential philosophy. Her project was called On the concept of love in the thought of Saint Augustine. She remained lifelong friends with Jaspers and his wife. She also became friends with other students and reconnected with Kurt Blumenfeld, who introduced her to Jewish politics. At Heidelberg, she lived near the Heidelberg Castle. A plaque on the wall marks where she lived.

After finishing her doctorate, Hannah planned to pursue a teaching career. However, 1929 was also the year of the Great Depression. This made the Weimar Republic in Germany very unstable. As a Jewish person, Hannah had little chance of getting a university job in Germany. Still, she completed most of her work before she was forced to leave Germany.

Career and Exile

Germany (1929–1933)

In 1929, Hannah Arendt met Günther Stern again in Berlin. They started a relationship and married on September 26. They had a lot in common, and their parents were happy about the marriage. Hannah received a grant to support her research, with help from Heidegger and Jaspers. She also worked on getting her doctorate project published.

For two years, Hannah and Günther moved around, trying to find Günther an academic job. They lived in Drewitz, then Heidelberg, and then Frankfurt. In Frankfurt, Hannah attended lectures by other important thinkers. They worked together on articles. When it became clear Günther would not get a job, they returned to Berlin in 1931.

Back in Berlin, Günther got a job as a writer for a cultural newspaper. He started using the pen name Günther Anders. Hannah helped him with his work. Hannah had changed her research topic from German Romanticism to Rahel Varnhagen and the idea of assimilation. A friend had given her copies of Varnhagen's letters. Hannah saw herself in Rahel, especially their shared feelings and struggles. Rahel, like Hannah, found her purpose in her Jewish identity. Hannah Arendt later called Rahel Varnhagen's acceptance of her destiny a "conscious pariah." This was a personal trait Hannah recognized in herself.

In Berlin, Hannah became more involved in politics. She studied political ideas and read works by Marx and Trotsky. She did not see herself as a political leftist, but she felt her Jewish identity led her to activism. Her interest in Jewish politics led her to publish her first article on Judaism in 1932. She also wrote about the status of women. She was skeptical that the women's movement could bring political change on its own. She believed it should work with men on broader political goals, similar to Rosa Luxemburg's views. Hannah always put political questions first, before social ones.

By 1932, the political situation in Germany was getting worse. Hannah was worried about reports that Heidegger was speaking at National Socialist meetings. She asked him to deny that he supported National Socialism, but he did not. As a Jewish person in Nazi Germany, Hannah was prevented from earning a living and faced discrimination. She knew she would likely have to leave Germany. Jaspers tried to convince her to see herself as German first. But she disagreed, saying that for her, Germany was her "mother tongue, philosophy, and poetry," not her identity.

By 1933, life for Jewish people in Germany was very dangerous. Adolf Hitler became Chancellor in January. The Reichstag fire in February led to the suspension of civil liberties. Attacks on left-wing groups and Communists increased. Günther, who had communist connections, fled to Paris. But Hannah stayed to become an activist. She used her apartment in Berlin as a safe house for people trying to escape. A plaque on the wall now honors her rescue efforts there.

Hannah had already criticized the Nazi Party in 1932. When anti-Jewish laws and boycotts began in spring 1933, she decided: "If one is attacked as a Jew one must defend oneself as a Jew." This idea of the Jew as a "Pariah" (an outsider) became important in her later writings. She published parts of her biography of Rahel Varnhagen, arguing that the time of Jewish assimilation had ended.

Hannah wanted to tell the world what was happening to Jewish people in Germany. She became friends with Zionist activists and started researching antisemitism. She used her access to the Prussian State Library to gather evidence for a speech at the Zionist Congress in Prague. This research was illegal. A librarian reported her for anti-state propaganda. Hannah and her mother were arrested by the Gestapo and spent eight days in prison. Her notebooks were in code, so they couldn't be understood. A sympathetic officer released her to await trial.

Exile: France (1933–1941)

Paris (1933–1940)

After her release, Hannah realized the danger. She and her mother fled Germany, crossing the mountains into Czechoslovakia and then taking a train to Geneva. In Geneva, she decided to dedicate herself to "the Jewish cause." She worked for the League of Nations' Jewish Agency for Palestine, distributing visas and writing speeches.

From Geneva, Hannah and her mother traveled to Paris in the autumn. There, Hannah reunited with Stern. She became friends with Stern's cousin, the philosopher Walter Benjamin, and the French philosopher Raymond Aron. Hannah was now an émigrée, an exile without official papers. She had turned her back on Nazi Germany. Her legal status was uncertain, and she struggled with a new language and culture.

In 1934, she started working for a Zionist program. She gave lectures and organized clothing, documents, medicine, and education for young Jewish people wanting to move to Palestine. She learned French, Hebrew, and Yiddish to improve her skills. This work helped her support herself and her husband. When that organization closed in 1935, she worked for Baroness Germaine Alice de Rothschild, helping with Jewish charities.

Later in 1935, Hannah joined Youth Aliyah (Youth Immigration). This organization helped many people escape the coming Holocaust. Hannah eventually became its Secretary-General (1935–1939). Her work involved finding food, clothing, social workers, and lawyers, but mostly raising money. She visited Palestine for the first time in 1935. With the Nazi takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938, Paris was filled with refugees. Hannah became a special agent to rescue children from these countries. In 1938, she finished her biography of Rahel Varnhagen, but it was not published until 1957. In April 1939, after the terrible Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) in November 1938, Hannah's mother decided to leave her husband and join Hannah in Paris.

Heinrich Blücher

In 1936, Hannah met Heinrich Blücher (1899–1970) in Paris. He was a self-taught poet and philosopher from Berlin. Blücher had been involved in political groups. Although Hannah had rejoined Stern in 1933, their marriage was effectively over. She divorced Stern in 1937, the same year she lost her German citizenship. She began living with Blücher, and his long history of political activism started to shift Hannah's own thinking towards political action. Hannah and Blücher married on January 16, 1940.

Internment and Escape (1940–1941)

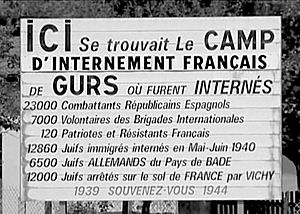

On May 5, 1940, as Germany prepared to invade France, the military governor of Paris ordered all "enemy foreigners" (mostly Jewish people from Germany) to report for internment (being held in camps). Women were gathered at the Vélodrome d'Hiver on May 15. Hannah's mother, being over 55, was allowed to stay in Paris. Hannah described how refugees were "put into concentration camps by their foes and into internment camps by their friends." The men, including Blücher, were sent to Camp Vernet in southern France. Hannah and other women were sent to Camp Gurs a week later.

On June 22, France surrendered to Germany. Gurs was in the southern part of France controlled by the Vichy government. Hannah described how, "in the resulting chaos we succeeded in getting hold of liberation papers." She escaped with about 200 of the 7,000 women held there, about four weeks later. She managed to walk and hitchhike north to Montauban, where she knew she would find help. Blücher also escaped from his camp and made his way to Montauban. Soon, Anne Mendelssohn and Hannah's mother joined them.

Escaping France was very hard without official papers. Their friend Walter Benjamin took his own life after being caught trying to escape to Spain. An American journalist, Varian Fry, helped many people escape from Marseilles. With help from Günther Stern, Hannah, her husband, and her mother managed to get the necessary permits. In January 1941, they traveled by train through Spain to Lisbon, Portugal. They eventually got passage to New York in May on the S/S Guiné II. A few months later, Fry's operations were shut down, and the borders were sealed.

New York (1941–1975)

World War II (1941–1945)

When they arrived in New York City on May 22, 1941, with very little, they received help from the Zionist Organization of America and German immigrants. They rented rooms at 317 West 95th Street, and Hannah's mother joined them in June. Hannah needed to learn English quickly. She spent two months with an American family in Winchester, Massachusetts. She found the experience difficult but observed that America had "political freedom coupled with social slavery."

Back in New York, Hannah wanted to start writing again. She became active in the German-Jewish community. In July 1942, she published her first article, "From the Dreyfus Affair to France Today." In November 1941, she was hired by the New York German-language Jewish newspaper Aufbau. From 1941 to 1945, she wrote a political column for it, covering antisemitism, refugees, and the need for a Jewish army. She also wrote for other Jewish and German immigrant publications.

Hannah's first full-time paid job came in 1944. She became the director of research for the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction. She was chosen because of her interest, experience, and connections to Germany. In this role, she made lists of Jewish cultural items in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe. This was to help recover them after the war. She and her husband lived at 370 Riverside Drive in New York City. Blücher taught at nearby Bard College for many years.

After the War (1945–1975)

In July 1946, Hannah left her job at the Commission to become an editor at Schocken Books. This company later published some of her works. In 1948, she became involved in the efforts to find a solution for the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. She was against creating a purely Jewish nation-state in Palestine. Instead, she supported including Palestine in a multi-ethnic federation. She believed this would help Jewish people who had no country and avoid problems with nationalism. In 1948, she supported a single, shared state to prevent the land from being divided.

She returned to the Commission in August 1949. As executive secretary, she traveled to Europe. She worked in Germany, Britain, and France from December 1949 to March 1950. She negotiated the return of historical documents from German institutions. She found this work frustrating but sent regular reports. In January 1952, she became secretary to the Board. The organization's work was slowing down, and she was also working on her own intellectual projects. She kept this position until her death. Hannah's work on cultural recovery gave her more material for her study of totalitarianism.

In the 1950s, Hannah Arendt wrote The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), The Human Condition (1958), and On Revolution (1963). She started writing to the American author Mary McCarthy in 1950, and they became lifelong friends. In 1950, Hannah also became a naturalized citizen of the United States. The same year, she started seeing Martin Heidegger again. During this time, Hannah defended him against critics who pointed out his support for the Nazi Party. She said Heidegger was a naive man caught up in forces he couldn't control. She also said that his philosophy had nothing to do with National Socialism. In 1961, she went to Jerusalem to report on Eichmann's trial for The New Yorker. This report made her widely known and caused much discussion. She received many awards for her work, including the Danish Sonning Prize in 1975 for her contributions to European civilization.

A few years later, she spoke in New York City about whether violence could be a political act. She said, "Generally speaking, violence always rises out of impotence. It is the hope of those who have no power to find a substitute for it and this hope, I think, is in vain. Violence can destroy power, but it can never replace it."

Teaching Career

Hannah Arendt taught at many universities starting in 1951. However, she always refused permanent teaching positions to keep her independence. Before becoming a university professor at the New School for Social Research in New York City, she was a visiting scholar at the University of Notre Dame, University of California, Berkeley, Princeton University (where she was the first woman to be appointed a full professor in 1959), and Northwestern University. She also taught at the University of Chicago from 1963 to 1967. She was a university professor at The New School from 1967. She was also a fellow at Yale University and the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University. She became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1962 and the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1964.

In 1974, Hannah helped create a special program at Stanford University called Structured Liberal Education (SLE). She wrote a letter to Stanford's president to support a professor's idea for a humanities program. At the time of her death, she was a University Professor of Political Philosophy at The New School.

Personal Relationships

Besides her marriages, Hannah Arendt had many close friendships. After her death, her letters with many friends were published. These letters show a lot about her thinking. She was loyal and generous to her friends, dedicating some of her books to them. She described friendship as an "active mode of being alive." For her, friendship was very important to her life and to the idea of politics. One friend said she had a "genius for friendship."

Her friendships based on philosophy were mostly with men from Europe. Her later American friendships were more varied, including writers and political figures. Even though she became an American citizen in 1950, her cultural roots stayed European. She continued to speak German, her "mother tongue." She surrounded herself with German-speaking immigrants, sometimes called "The Tribe." For her, "real people" were "pariahs." This didn't mean outcasts, but outsiders who didn't fully fit in. She believed their "social nonconformism" was important for intellectual achievement.

Hannah always had a "best friend." In her teenage years, she became lifelong friends with Anne Mendelssohn Weil. After she moved to America, Hilde Fränkel, who was Paul Tillich's secretary, became her closest friend until Hilde died in 1950. After the war, Hannah was able to visit Germany and renew her friendship with Anne Weil. Anne visited New York several times, especially after Blücher's death in 1970. Their last meeting was in Switzerland in 1975, shortly before Hannah's death. After Hilde Fränkel's death, Mary McCarthy became Hannah's closest friend and confidante.

Final Years and Passing

Heinrich Blücher had a cerebral aneurysm in 1961 and remained unwell after 1963, suffering several heart attacks. He died on October 31, 1970, from a massive heart attack. Hannah was heartbroken. She had told Mary McCarthy, "Life without him would be unthinkable." Hannah herself had a serious heart attack while lecturing in Scotland in May 1974. Although she recovered, her health remained poor. On the evening of December 4, 1975, shortly after her 69th birthday, she had another heart attack in her apartment while with friends. She was pronounced dead at the scene. Her ashes were buried next to Blücher's at Bard College in May 1976.

After Hannah's death, the title page of the final part of her last book, The Life of the Mind ("Judging"), was found in her typewriter. She had just started it. This page has been reproduced since then.

Key Works

Hannah Arendt wrote about intellectual history as a political thinker. She used events and actions to understand modern totalitarian movements. She also explored the threat to human freedom from scientific ideas and common morality. She was an independent thinker and did not belong to any specific school of thought. Besides her major books, she published collections of essays like Between Past and Future (1961), Men in Dark Times (1968), and Crises of the Republic (1972). She also wrote for many magazines. She is perhaps most famous for her reports on the Adolf Eichmann trial, which caused a lot of discussion.

Political Ideas

Hannah Arendt did not create a single, fixed political theory. Her writings are hard to put into one category. However, her ideas are often linked to civic republicanism, which focuses on active citizenship. This means people being involved in their community and discussing things together. She believed that even in bad governments, human freedom could never be completely destroyed. She thought that modern societies often choose the comfort of rules over the freedom of democracy. Her most important political message is her strong defense of freedom in a world that is becoming less free. She covers topics like totalitarianism, revolution, freedom, and the abilities of thinking and judging.

Love and Saint Augustine (1929)

Hannah Arendt's doctorate project, Love and Saint Augustine, was published in 1929. It received good reviews, but an English translation didn't appear until 1996. In this work, she combined ideas from both Heidegger and Jaspers. Hannah's interpretation of love in Augustine's work looks at three types: love as desire, love between humans and their creator, and love for one's neighbor. She saw love for one's neighbor as the most important. Augustine's ideas continued to influence Hannah's writings throughout her life.

Some of the main themes of her later work were already present here. She introduced the idea of "natality" (being born) as a key part of human existence. She developed this further in The Human Condition (1958). She explained that natality meant new beginnings and humans being like "new creations." The idea of birth and renewal is important from her first book to her last.

Love is another connecting theme. The phrase amor mundi (love of the world) is often linked to Hannah Arendt. It was a strong passion throughout her work. She took the phrase from Augustine's writings. Amor mundi was her original title for The Human Condition (1958).

The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

Hannah Arendt's first major book, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), looked at the beginnings of Stalinism and Nazism. It was divided into three parts: "Antisemitism," "Imperialism," and "Totalitarianism." Hannah argued that totalitarianism was a "new form of government." It was different from other types of harsh rule like despotism or dictatorship. Totalitarianism used terror to control large groups of people, not just political enemies. Hannah also said that being Jewish was not the only reason for the Holocaust. Nazism was about terror and strict control, not just getting rid of Jewish people. She explained this tyranny using Kant's phrase "radical evil." This meant that victims became "superfluous people." In later versions, she added more about "Ideology and Terror" and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

Some critics of Origins have focused on her idea that Hitlerism and Stalinism were equally tyrannical.

Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess (1957)

Hannah Arendt finished her work on Rahel Varnhagen while living in Paris in 1938. But it was not published until 1957. This book is a biography of a 19th-century Jewish socialite. It was an important step in Hannah's study of Jewish history. It looked at Jewish assimilation (fitting in) and emancipation (gaining rights). It also introduced her ideas about Jewish people in the Jewish diaspora as either pariahs (outsiders) or parvenus (people who gained wealth or status but are not accepted). The book also shows an early version of her ideas about history. The book is dedicated to Anne Mendelssohn, who first told her about Varnhagen. Hannah's connection to Varnhagen can be seen throughout her later work. Her story of Varnhagen's life was written during a time when German-Jewish culture was being destroyed. It partly reflects Hannah's own feelings as a German-Jewish woman forced out of her own culture into a stateless existence. Because of this, some call it "biography as autobiography."

The Human Condition (1958)

In what is probably her most important book, The Human Condition (1958), Hannah Arendt explains the differences between political and social ideas, labor and work, and different kinds of actions. She then explores what these differences mean. Her theory of political action, which involves a public space, is greatly developed in this book. Hannah argues that human life always develops within societies. But the political part of human nature, where individuals can achieve freedom, has only been truly realized in a few societies. She clearly defines different categories of ideas. While she puts labor and work in the social realm, she prefers the human condition of action. She sees action as both essential to existence and beautiful. Of human actions, Hannah identifies two that she considers vital: forgiving past wrongs and promising future benefits.

Hannah first introduced the idea of "natality" in her Love and Saint Augustine (1929). In The Human Condition, she develops this further. Here, she moves away from Heidegger's focus on death. Hannah's positive message is about the "miracle of beginning." This means the constant arrival of new things that create action and change situations caused by past actions. She wrote, "Men, though they must die, are not born in order to die but in order to begin." Natality became a central idea in her political theory. It is also seen as her most hopeful idea.

Between Past and Future (1961)

Between Past and Future is a collection of eight essays written between 1954 and 1968. These essays deal with different but connected philosophical topics. They share the main idea that humans live between the past and an uncertain future. Humans must always think to exist, but they must also learn how to think. People have relied on tradition, but they are losing respect for it and for culture. Hannah Arendt tries to find ways to help people think again. She believed that modern philosophy had not succeeded in helping humans live correctly.

On Revolution (1963)

Hannah Arendt's book On Revolution compares two major revolutions of the 18th century: the American and French Revolutions. She goes against common Marxist and leftist views. She argues that the French Revolution, though often studied, was a disaster. She believed the American Revolution, which was often ignored, was a success. The turning point in the French Revolution happened when leaders gave up their goals of freedom to focus on helping the poor masses. In the United States, the founders never gave up the goal of Constitutio Libertatis (establishing liberty). Hannah believed the revolutionary spirit of those men had been lost. She suggested a "council system" as a way to bring back that spirit.

Men in Dark Times (1968)

The collection of essays Men in Dark Times presents intellectual biographies. These are stories of the lives and ideas of important creative and moral figures of the 20th century. They include Walter Benjamin, Karl Jaspers, Rosa Luxemburg, and others.

Crises of the Republic (1972)

Crises of the Republic was Hannah Arendt's third collection of essays. It has four essays: "Lying in Politics," "Civil Disobedience," "On Violence," and "Thoughts on Politics and Revolution." These essays discuss American politics and the problems it faced in the 1960s and 1970s. "Lying in Politics" tries to explain why the government lied about the Vietnam War, as shown in the Pentagon Papers. "Civil Disobedience" looks at protest movements. "On Violence" argues that violence needs power, which she saw as belonging to groups. So, she disagreed with the idea that power comes from violence.

When Hannah Arendt died in 1975, she left a major work unfinished. It was later published in 1978 as The Life of the Mind. Since then, some of her smaller works have been collected and published. These include "Essays in Understanding" (1994), which covered the period 1930–1954. A new version of Origins of Totalitarianism appeared in 2004, followed by The Promise of Politics in 2005. This renewed interest led to another series of essays, Thinking Without a Banister: Essays in Understanding, 1953–1975, published in 2018. Other collections have focused on her Jewish identity, moral philosophy, and literary works.

The Life of the Mind (1978)

Hannah Arendt's last major work, The Life of the Mind, was not finished when she died. It marked a return to moral philosophy. The book was based on her university class called Philosophy of the Mind. She planned it as a three-part book about the mental activities of thinking, willing, and judging. Her most recent work had focused on the first two parts. Her discussion of thinking was based on Socrates and his idea of thinking as a private conversation with oneself. This led her to new ideas about conscience.

Hannah died suddenly five days after finishing the second part. The first page of the "Judging" section was still in her typewriter. Mary McCarthy then edited the first two parts and gave some hints about what the third part would have been. Hannah's exact plans for the third part are unknown. However, she left several writings about her thoughts on the mental ability of Judging. These have since been published separately.

Collected Writings

After Hannah Arendt's death, her essays and notes have continued to be published by friends and colleagues. These include writings that give insight into the unfinished third part of The Life of the Mind. The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age (1978) is a collection of 15 essays and letters from 1943–1966. It discusses the situation of Jewish people in modern times. This book was also very controversial. Another collection of her writings on being Jewish was published as The Jewish Writings (2007). Other works include a collection of essays called Essays in Understanding 1930–1954 (1994). The remaining essays were published as Thinking Without a Banister: Essays in Understanding, 1953–1975 (2018). Her personal notebooks, which are like memoirs, were published in German in 2002.

Letters

More insight into her thinking comes from the ongoing publication of her letters. These include letters with important people in her life, such as Karl Jaspers (1992), Mary McCarthy (1995), Heinrich Blücher (1996), Martin Heidegger (2004), and others. Other published letters include those with women friends like Hilde Fränkel and Anne Mendelsohn Weil.

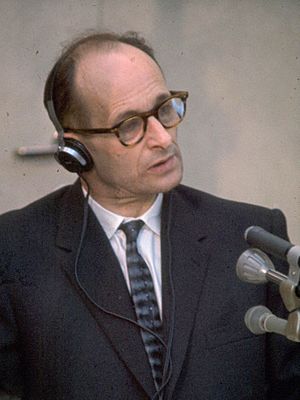

Hannah Arendt and the Eichmann Trial (1961–1963)

In 1960, Hannah Arendt heard about Adolf Eichmann's capture and upcoming trial. She contacted The New Yorker and offered to report on it when it started on April 11, 1961. Hannah wanted to test her ideas from The Origins of Totalitarianism. She also wanted to see how justice would be given to a man like Eichmann. She had not seen much of the Nazi regime directly, so this was a chance to see a leader of totalitarianism up close. The New Yorker accepted her offer. She attended six weeks of the five-month trial with her young cousin.

In her 1963 report, which became the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Hannah Arendt used the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe Eichmann. She, like others, was surprised by how ordinary he seemed. He looked like a small, balding, mild-mannered office worker. This was a stark contrast to the terrible crimes he was accused of. She wrote that he was "terribly and terrifyingly normal." She explored whether evil is deeply rooted or simply comes from not thinking. She wondered if ordinary people obey orders and follow popular opinion without thinking about the results of their actions. Hannah's argument was that Eichmann was not a monster. She contrasted the huge scale of his actions with how ordinary he seemed. Eichmann, she said, even called himself a Zionist and initially opposed the persecution of Jews. He expected his captors to understand him. She pointed out that his actions were not driven by meanness. Instead, they came from a blind loyalty to the Nazi government and a need to belong.

Hannah later said, "Going along with the rest and wanting to say 'we' were quite enough to make the greatest of all crimes possible." What Hannah observed during the trial was an ordinary sales clerk. He found a purpose and importance for himself in the Nazi movement. She noted that his use of common phrases and bureaucratic rules stopped him from questioning his actions or "thinking." This led her to her most debated statement: "the lesson that this long course in human wickedness had taught us – the lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil." By saying Eichmann did not think, she did not mean he was unaware of his actions. She meant he lacked deep, reflective thought.

Hannah Arendt criticized how the Israelis conducted the trial. She saw it as a "show trial" with other goals besides simply finding evidence and giving justice. Hannah also criticized Israel for showing Eichmann's crimes as crimes against a nation-state, rather than against all humanity. She disagreed with the idea that a strong Israel was needed to protect Jewish people worldwide. She felt the prosecutor, Attorney General Gideon Hausner, used exaggerated language to support Prime Minister Ben-Gurion's political goals. Hannah, who believed she could focus on moral principles, became frustrated with Hausner. She described his parade of survivors as having "no apparent bearing on the case." She was especially concerned that Hausner kept asking "why did you not rebel?" instead of questioning the role of Jewish leaders. On this point, Hannah argued that during the Holocaust, some Jewish leaders cooperated with Eichmann "almost without exception." These leaders formed the Jewish Councils (Judenräte). She had concerns about this before the trial. She called this a moral disaster. Her argument was not to blame, but to mourn what she saw as a moral failure. She believed it was wrong to compromise the idea that it is better to suffer wrong than to do wrong. She described the cooperation of Jewish leaders as a breakdown of Jewish morality: "This role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter in the whole dark story." This idea was widely misunderstood. It caused even greater controversy and anger towards her in the Jewish community and in Israel. For Hannah Arendt, the Eichmann trial changed her thinking in the last ten years of her life. She became more focused on moral philosophy.

"No One Has the Right to Obey"

In a 1964 interview, Hannah Arendt was asked about Eichmann's defense. He claimed he had followed Kant's idea of duty and obedience his whole life. Hannah replied that this was outrageous. She said Eichmann was misusing Kant's ideas. Kant's moral philosophy is about a person's ability to judge their own actions, which means not blindly obeying. She stated, "No man has, according to Kant, the right to obey."

Kant clearly defines a higher moral duty than just obeying authority. Hannah herself wrote in her book, "This was outrageous, on the face of it, and also incomprehensible, since Kant's moral philosophy is so closely bound up with man's faculty of judgment, which rules out blind obedience." Hannah's reply was later shortened to "No one has the right to obey." This phrase has been widely used, and it captures an important part of her moral philosophy.

The phrase "No one has the right to obey" has become one of her most famous sayings. It appears on the wall of the house where she was born. In 2017, a fascist sculpture in Italy was changed to show Hannah Arendt's words on obedience in three languages. The phrase has also appeared in other art with political messages. It represents the idea of resisting dictatorship, as she wrote in her essay "Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship" (1964).

Views and Legacy

Views on Human Rights

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt wrote a long chapter called The Decline of the Nation-State and the End of the Rights of Man. In it, she critically analyzed human rights. This chapter has been called "the most widely read essay on refugees ever published." Hannah was not against the idea of political rights in general. Instead, she supported the idea of rights based on belonging to a nation or a community. Human rights, or the Rights of Man, are thought to be universal and belong to everyone just because they are human. In contrast, civil rights belong to people because they are part of a political community, usually as citizens.

Hannah's main criticism of human rights was that they were ineffective and an illusion. This is because enforcing them conflicts with a nation's independence. She argued that there is no power higher than sovereign nations. So, governments have little reason to respect human rights if those rights conflict with their national interests. This can be seen most clearly when looking at how refugees and stateless people are treated. Since a refugee has no state to protect their civil rights, the only rights they have are human rights. In this way, Hannah used the refugee as a test case to examine human rights separately from civil rights.

Hannah's analysis was based on the large movements of refugees in the first half of the 20th century. It also drew from her own experience as a refugee fleeing Nazi Germany. She argued that as governments started to emphasize national identity for full legal status, the number of minority foreigners increased. So did the number of stateless people whom no state would legally recognize. The two possible solutions for refugees, sending them back home or making them citizens, both failed to solve the crisis. Hannah argued that sending them back home failed because no government wanted to take them in. When refugees were forced into other countries, it was seen as illegal immigration. So, their basic status as stateless people did not change. Attempts to make refugees citizens also had little success. This failure was mainly because governments and most citizens resisted. They saw refugees as unwanted people who threatened their national identity. Refugees themselves also resisted becoming fully assimilated. They tried to keep their own ethnic and national identities. Hannah believed that neither citizenship nor the tradition of offering asylum could handle the huge number of refugees. Instead of accepting some refugees with legal status, states often took away the citizenship of minorities who shared national or ethnic ties with stateless refugees.

Hannah argued that the consistent mistreatment of refugees, many of whom were put in internment camps, showed that human rights did not truly exist. If human rights are truly universal and cannot be taken away, they should be possible to achieve within modern liberal states. She concluded, "The Rights of Man, supposedly inalienable, proved to be unenforceable–even in countries whose constitutions were based upon them–whenever people appeared who were no longer citizens of any sovereign state." Hannah believed they were not achievable because they conflicted with a key feature of liberal states: national independence. One main way a nation shows its independence is by controlling its borders. Governments usually allow their citizens to move freely across borders. But the movement of refugees is often restricted in the name of national interests. This creates a problem for liberal ideas. This is because liberal thinkers usually support both human rights and the existence of independent nations.

Feminism

Hannah Arendt is seen by many feminists as a pioneer in a world mostly run by men. However, she did not call herself a feminist. She would have been surprised to be described as one. She remained against the social goals of the Women's Liberation movement. She encouraged independence but always kept in mind Vive la petite différence! (Long live the small difference!). When she became the first woman professor at Princeton in 1953, the media focused on this special achievement. But she never wanted to be seen as an exception, either as a woman or a Jewish person. She said, "I am not disturbed at all about being a woman professor, because I am quite used to being a woman." In 1972, discussing women's liberation, she said, "the real question to ask is, what will we lose if we win?" She enjoyed what she saw as the advantages of being feminine, not feminist. One friend described her as "Intensely feminine and therefore no feminist." Hannah Arendt thought some jobs and positions were not suitable for women, especially those involving leadership. She told Günter Gaus, "It just doesn't look good when a woman gives orders." Despite these views, and being called "anti-feminist," much has been written about her place in relation to feminism. In her last years, her views changed as a new feminist movement grew in America in the 1970s. She began to recognize the importance of the women's movement.

Lasting Impact

Hannah Arendt is considered one of the most influential political philosophers of the 20th century. In 1998, Walter Laqueur said, "No twentieth-century philosopher and political thinker has at the present time as wide an echo." She is seen as a philosopher, historian, sociologist, and journalist. Some have even called her legacy a "cult." In a 2016 review of a documentary about her, a journalist described Hannah Arendt as a thinker of "unmatched range and rigor." However, she is mostly known for her article Eichmann in Jerusalem and especially for the phrase "the banality of evil."

She avoided public attention. She told Karl Jaspers in 1951 that she never expected to see herself on the cover of magazines. In Germany, there are tours of places connected to her life.

The study of Hannah Arendt's life and work is called "Arendtian." In her will, she created the Hannah Arendt Bluecher Literary Trust to protect her writings and photographs. Her personal library, with about 4,000 books, was given to Bard College in 1976. The college has started to digitize some of the collection. Most of her papers are at the Library of Congress. Her letters with German friends and teachers are in the German Literature Archive in Marbach. In 1998, the Library of Congress listed over 50 books written about her, and that number has grown.

Her life and work are recognized by the universities where she taught. There are Hannah Arendt Centers at Bard College and The New School in New York. In Germany, her contributions to understanding authoritarianism are recognized by the Hannah-Arendt-Institut für Totalitarismusforschung in Dresden. There are also Hannah Arendt Associations, like the one in Bremen that gives an annual award for political thinking. In Oldenburg, the Hannah Arendt Center at Carl von Ossietzky University was founded in 1999. It has a large collection of her work and runs an online journal called HannahArendt.net. In Italy, the Hannah Arendt Center for Political Studies is at the University of Verona.

In 2017, a journal called Arendt Studies was launched. It publishes articles about Hannah Arendt's life, work, and legacy. Many places connected to her display items about her, like her student ID card at the University of Heidelberg. In 2006, the anniversary of her birth, there were conferences and celebrations of her work around the world.

In 2015, filmmaker Ada Ushpiz made a documentary about Hannah Arendt called Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt. The New York Times called it a "critics pick." Of the many photos of Hannah Arendt, the one taken in 1944 by Fred Stein has become very famous. It has even appeared on a German postage stamp. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) is among the organizations that have recognized Hannah Arendt's contributions to civilization and human rights.

Modern Relevance

The rise of nativism (favoring native-born citizens over immigrants) and concerns about increasingly authoritarian governments have led to a new interest in Hannah Arendt and her writings. People are revisiting her ideas to see how they help us understand modern movements, which are sometimes called "Dark Times." For example, Amazon reported that it sold out of copies of The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951). Michiko Kakutani has written about what she calls "the death of truth." In her 2018 book, The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump, she argues that the rise of totalitarianism has been built on lies.

Kakutani and others believe that Hannah Arendt's words apply not just to events of the past century but also to today's world, filled with fake news and lies. It is also important that Hannah Arendt looked at history more broadly than just totalitarianism in the early 20th century. She said, "the deliberate falsehood and the outright lie have been used as legitimate means to achieve political ends since the beginning of recorded history."

The phrase "No one has the right to obey" is increasingly used today. It means that actions come from choices and judgment. We cannot avoid responsibility for what we have the power to do. Also, the centers created to promote Arendtian studies continue to look for solutions to many modern problems in her writings.

Hannah Arendt's ideas on obedience have also been linked to the controversial psychology experiments by Stanley Milgram. These experiments suggested that ordinary people can easily be made to commit terrible acts. Milgram himself pointed this out in 1974. He said he was testing the idea that people like Eichmann would just follow orders. But unlike Milgram, Hannah argued that actions involve responsibility.

Hannah Arendt's theories on how nations deal with refugees remain important today. She saw firsthand how large groups of stateless people, without rights, were displaced. They were treated not as people in need, but as problems to solve, and often resisted. She wrote about this in her 1943 essay "We refugees." Another idea from Hannah that is still relevant today is her observation, inspired by Rilke, about the sadness of not being heard. This is the feeling that a tragedy has no one to listen, comfort, or intervene. An example of this is gun violence in America and the lack of political action that follows.

In Search of the Last Agora, a documentary film about Hannah Arendt's 1958 book The Human Condition, was released in 2018. The film explores "new meaning in the political theorist's conceptions of politics, technology and society in the 1950s." It especially looks at her predictions of problems that were unknown in her time, like social media, intense globalization, and obsessive celebrity culture.

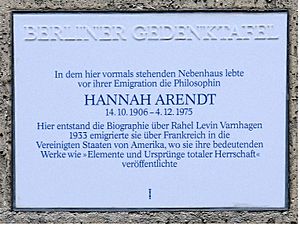

Commemorations

Hannah Arendt's life and work are remembered in many ways. These include plaques marking places where she lived. Public places and institutions, including schools, are named after her. There is also a Hannah Arendt Day in her birthplace. Things named after her range from asteroids to trains. She has also been honored on stamps. Museums and foundations bear her name.

See also

In Spanish: Hannah Arendt para niños

In Spanish: Hannah Arendt para niños

- American philosophy

- German philosophy

- Hannah Arendt Award

- List of refugees

- List of women philosophers

- Women in philosophy

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |