Günther Anders facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Günther Anders

|

|

|---|---|

Anders in 1929

|

|

| Born |

Günther Siegmund Stern

12 July 1902 Breslau, German Empire (now Wrocław, Poland)

|

| Died | 17 December 1992 (aged 90) Vienna, Austria

|

| Alma mater | University of Freiburg |

| Spouse(s) |

Elisabeth Freundlich

(m. 1945; div. 1955)Charlotte Lois Zelka

(m. 1957) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy, phenomenology |

Günther Anders (born Günther Siegmund Stern, 12 July 1902 – 17 December 1992) was a German thinker, writer, and journalist. He focused on how modern technology affects human life and society.

Anders studied philosophy and later worked as a journalist. He changed his name from Stern to Anders. He had to leave Germany because of the Nazis and moved to the United States. After returning to Europe, he wrote his most famous book, The Obsolescence of Humankind, in 1956.

A big part of Anders' work looked at how humans might destroy themselves. He thought about big events like the Holocaust and the danger of nuclear weapons. He explored how mass media changes our feelings and choices, and what it means to be a thinker in a world full of technology. He received the Sigmund Freud Prize in 1992, shortly before he passed away.

Contents

Life and Times

Early Years and Family

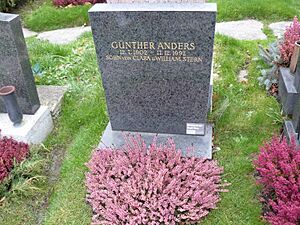

Günther Anders was born on 12 July 1902, in Breslau, which is now Wrocław in Poland. His parents, Clara and William Stern, were famous psychologists who studied how children develop. He was also a cousin of the philosopher Walter Benjamin.

His parents kept detailed diaries about Günther and his two sisters, Hilde and Eva, from 1900 to 1912. These diaries were part of their studies on child psychology.

Anders did not believe in God and was an atheist. He studied philosophy at the University of Freiburg in the late 1920s. In 1923, he earned his PhD in philosophy. His teacher was Edmund Husserl.

While working as a journalist in Berlin, he changed his last name from Stern to "Anders." "Anders" means "other" or "different" in German. One reason he changed his name was to avoid being too closely linked to his well-known parents.

In 1929, he married Hannah Arendt, who was also a student of philosophy.

Living in Exile

In 1933, Anders had to leave Nazi Germany because of the political situation. He first went to France. In 1936, he moved to the United States.

In the U.S., he lived in New York and California. He worked many different jobs, including writing for a journal, reviewing books, tutoring, and even working in a factory. He also gave lectures at The New School for Social Research.

In 1945, Anders married for a second time to Austrian writer Elisabeth Freundlich.

Return to Europe

Anders returned to Europe in 1950 with his wife and settled in Vienna, Austria. There, he wrote his most important philosophical book, The Obsolescence of Humankind (published in 1956).

He became a key leader in the movement against nuclear weapons. He wrote many essays and expanded his diaries, including one about a trip to Auschwitz. Anders and his second wife divorced in 1955.

In 1957, Anders married for a third time to American pianist Charlotte Lois Zelka. Günther Anders himself knew how to play both the piano and the violin.

Ideas and Philosophy

Günther Anders called his way of thinking "occasional philosophy." He also described himself as a "critical thinker about technology." He was well-known in Europe, and many of his works were published in German.

Anders was one of the first thinkers to criticize the role of technology in modern life. He was especially critical of television. In his essay "The Phantom World of TV" (from the late 1950s), he explained how TV replaces real experiences with images. He believed this made people less likely to have their own experiences in the world.

The Obsolescence of Humankind

His most important work is Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen, which means "The Antiquatedness of the Human Being." In this book, Anders argues that there is a growing gap between what humans can create and destroy with technology, and our ability to truly understand or imagine that destruction.

Anders spent a lot of time thinking about the danger of nuclear weapons. He was an early critic of this technology. The book is made up of philosophical essays that often start with observations from his own diaries.

For example, he wrote about "Promethean Shame." This is the feeling of shame we might have when we see how amazing manufactured goods are, and we feel "embarrassed" that we were born naturally and not made perfectly like machines.

The Promethean Gap

Anders also talked about the "Promethean gap." This idea comes from the Greek myth of Prometheus, who brought fire and knowledge to humans. For Anders, Prometheus means "he who thinks ahead."

The Promethean gap refers to the problem that our ability to create and destroy has grown much faster than our ability to imagine the consequences of our actions. We can build and destroy much more than we can truly understand or control. For instance, it's easy to build something, but very hard to destroy it in a controlled way, especially something as powerful as a nuclear weapon.

Open Letter to Klaus Eichmann

Anders wrote We Sons of Eichmann: Open Letter to Klaus Eichmann. This book explored the moral questions raised by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi official involved in the Holocaust.

Anders suggested that the name "Eichmann" could refer to anyone who took part in, ignored, or knew about the Nazis' mass murders but did nothing to stop them. He wanted young people in Austria and Germany to understand that they should reject the actions of their parents' generation if those actions were wrong.

Mensch ohne Welt

In Mensch ohne Welt (Man Without World), Anders criticized modern society, especially how it values people based on their work. He believed that this society is not truly fit for human beings. In this view, people are seen as valuable only if they can sell their labor, rather than being valued simply for being human.

Awards and Recognition

- 1962: Omegna Award of the Italian Resistance

- 1967: German Critics Prize

- 1978: Grand Literature Prize of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts

- 1983: Theodor W. Adorno Award

- 1979: Austrian State Prize for Cultural Journalism

- 1985: Andreas Gryphius Prize (rejected)

- 1992: Honorary doctorate from the University of Vienna (rejected)

- 1992: Sigmund Freud Prize

Günther Anders Prize for Critical Thinking

The Günther Anders Prize for critical thinking is an award given every two years. It is presented by the International Günther Anders Society. Winners have included Joseph Vogl and Corine Pelluchon.

Selected Writings

- The Hunger March (1935)

- Kafka Pro and Contra: The Trial Records (1951, 1985)

- The Obsolescence of Humankind

- Volume I: On the Soul in the Era of the Second Industrial Revolution (1956)

- Volume II: On the Destruction of Life in the Era of the Third Industrial Revolution (1980)

- The Man on the Bridge: Diary from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1959)

- Hiroshima is Everywhere

- The View from the Tower. Tales. (1932)

- On Heidegger.

- Homeless Sculpture, On Rodin.

- Visit to Hades. Auschwitz and Breslau (1966)

- Visit Beautiful Vietnam: ABC of Today's Aggression.

- Thesis on the Legitimacy of Violence as a Form of Self-Defense Against the Nuclear Threat to Humanity.

- My Jewishness. (1978)

- Heresies. (1996)

- Philosophical Notes in Shorthand. (2002)

- Daily Notes: Records 1941–1992. (2006)

- The Writing on the Wall. (1967)

- Narratives. Gay Philosophy. (1983)

- Man Without World.

- Hunger March.

- The Atomic Threat. Radical Considerations.

- Exaggerations Towards Truth. Thoughts and Aphorisms.

- Love Yesterday. Notes on the History of Feelings. (1986)

- View from the Moon. Reflections on Space Flights. (1994)

- Nuernberg and Vietnam. Synoptical Mosaic. (1968)

- George Grosz. (1961)

- The Dead. Speech on three world wars. (1966)

- On Philosophical Diction and the Problem of Popularization. (1992)

- The World as Phantom and Matrix. (1990)

- The Final Hours and the End of All Time. Thoughts on the Nuclear Situation. (1972)

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |