Ernst Cassirer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ernst Alfred Cassirer

|

|

|---|---|

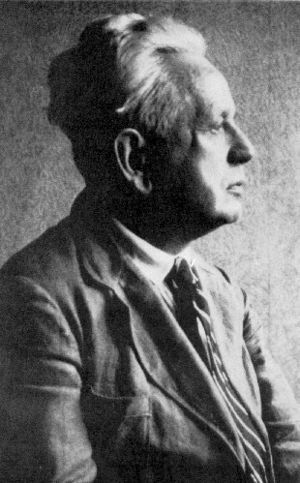

Cassirer in about 1935

|

|

| Born |

Ernst Alfred Cassirer

July 28, 1874 |

| Died | April 13, 1945 (aged 70) New York City, U.S.

|

| Education | University of Marburg (PhD, 1899) University of Berlin (Dr. phil. habil., 1906) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neo-Kantianism (Marburg School) Phenomenology |

| Theses |

|

| Academic advisors | Hermann Cohen Paul Natorp |

|

Main interests

|

Epistemology, aesthetics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Philosophy of symbolic forms Animal symbolicum |

|

Influenced

|

|

Ernst Alfred Cassirer (July 28, 1874 – April 13, 1945) was an important German philosopher. He was trained in a school of thought called Neo-Kantianism, which focused on how we gain knowledge. He first followed his teacher, Hermann Cohen, in trying to create a philosophy of science based on idealism (the idea that reality is based on our minds or ideas).

After Cohen's death in 1918, Cassirer developed a new idea about symbolism. He used this idea to expand the study of knowledge into a broader philosophy of culture. Cassirer was one of the leading thinkers in the 20th century who supported philosophical idealism. His most famous work is the Philosophy of Symbolic Forms (1923–1929).

Even though his work received mixed reactions after his death, more recent studies have shown Cassirer's role. He was a strong supporter of the moral ideas of the Enlightenment era. He also defended liberal democracy when fascism was rising, making such ideas unpopular. Within the international Jewish community, Cassirer's work is also seen as part of a long tradition of ethical philosophy.

Biography of Ernst Cassirer

Early Life and Education

Ernst Cassirer was born in Breslau, a city in Silesia (which is now part of Poland). He came from a Jewish family. He studied literature and philosophy at the University of Marburg. In 1899, he finished his doctoral degree there. His paper was about René Descartes's ideas on mathematical and scientific knowledge.

Later, he completed his habilitation (a higher academic qualification) in 1906 at the University of Berlin. His paper for this was about "The Problem of Knowledge in Philosophy and Science in the Modern Age."

Academic Career and Exile

Cassirer supported the liberal German Democratic Party (DDP) in politics. For many years, he worked as a private lecturer at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. In 1919, he became a philosophy professor at the new University of Hamburg. He taught there until 1933, guiding students like Joachim Ritter and Leo Strauss.

On January 30, 1933, the Nazi Regime came to power in Germany. Because he was Jewish, Cassirer left Germany on March 12, 1933. This was just one week after the first election under the Nazi government.

After leaving Germany, he taught for a few years at the University of Oxford in England. Then, he became a professor at Gothenburg University in Sweden. When Cassirer felt Sweden was no longer safe, he tried to get a job at Harvard University in the U.S. However, he was turned down because he had rejected a job offer from them 30 years earlier.

In 1941, he became a visiting professor at Yale University. Later, he moved to Columbia University in New York City. He taught there from 1943 until his death in 1945.

Later Years and Family

Ernst Cassirer died from a heart attack in April 1945 in New York City. A young rabbi named Arthur Hertzberg, who was one of Cassirer's students, led the funeral service. Cassirer is buried in Westwood, New Jersey. His grave is in the Cedar Park Beth-El Cemeteries, in the section for Congregation Habonim.

His son, Heinz Cassirer, also became a scholar who studied the philosopher Kant. Other famous members of his family included the neurologist Richard Cassirer, the publisher Bruno Cassirer, and the art dealer Paul Cassirer.

Cassirer's Key Philosophical Works

Understanding the History of Science

Cassirer's first important published works were about the history of modern thought. These writings covered the period from the Renaissance up to the philosopher Immanuel Kant. Following his Marburg Neo-Kantian ideas, he focused on epistemology, which is the study of how we know things.

His ideas about the scientific revolution influenced many historians. In books like The Individual and the Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy (1927), he saw science as a "Platonic" way of applying mathematics to nature.

Ideas on the Philosophy of Science

In his book Substance and Function (1910), Cassirer wrote about new developments in physics from the late 1800s. This included relativity theory and the basic ideas of mathematics. In Einstein's Theory of Relativity (1921), he argued that modern physics supported a Neo-Kantian way of understanding knowledge. He also wrote a book about Quantum mechanics called Determinism and Indeterminism in Modern Physics (1936).

Exploring the Philosophy of Symbolic Forms

While working in Hamburg, Cassirer discovered the Library of the Cultural Sciences, started by Aby Warburg. Warburg was an art historian interested in how rituals and myths show human emotions. In his Philosophy of Symbolic Forms (1923–29), Cassirer argued that humans are "symbolic animals". He explained this further in his 1944 book Essay on Man.

He believed that animals understand their world through instincts and direct senses. But humans create a world full of symbolic meanings. Cassirer was especially interested in natural language and myths. He suggested that science and mathematics grew out of natural language, and religion and art came from myths.

The Cassirer–Heidegger Debate

In 1929, Cassirer had an important discussion with another philosopher, Martin Heidegger, in Davos. This event is known as the Cassirer–Heidegger debate. Cassirer argued that while Kant's Critique of Pure Reason talks about how humans are limited by time, Kant also wanted to place human knowledge within a bigger idea of humanity. Cassirer challenged Heidegger's ideas by pointing to the universal truth found in science and moral studies.

Insights from Philosophy of the Enlightenment

Cassirer believed that when reason fully develops, it leads to human freedom. However, some scholars, like Mazlish (2000), note that Cassirer's book The Philosophy of the Enlightenment (1932) focused only on ideas. It did not fully explore the political and social situations of that time.

The Logic of Cultural Sciences

In The Logic of the Cultural Sciences (1942), Cassirer argued that objective and universal truth can be found in more than just the natural sciences. He believed it could also be found in practical, cultural, moral, and artistic parts of life. He said that just as natural sciences have universal laws, cultural sciences also have a similar type of shared, objective truth.

Understanding The Myth of the State

Cassirer's last book, The Myth of the State (1946), was published after he died. One of its goals was to understand the ideas that led to Nazi Germany. Cassirer saw Nazi Germany as a society where the dangerous power of myth was not controlled by stronger forces.

The book discusses the difference between logos (reason) and mythos (myth) in Greek thought. It also looks at Plato's Republic, medieval ideas about the state, and the writings of Niccolò Machiavelli. Cassirer also explored Thomas Carlyle's ideas on hero worship, the racial theories of Arthur de Gobineau, and the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

Cassirer claimed that in 20th-century politics, there was a return to the unreasonableness of myth. He felt this happened with the quiet agreement of Martin Heidegger. Cassirer believed that by moving away from Husserl's idea of an objective, logical basis for philosophy, Heidegger weakened philosophy's ability to fight against the rise of myth in German politics during the 1930s.

See also

In Spanish: Ernst Cassirer para niños

In Spanish: Ernst Cassirer para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |