Éric Weil facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Éric Weil

|

|

|---|---|

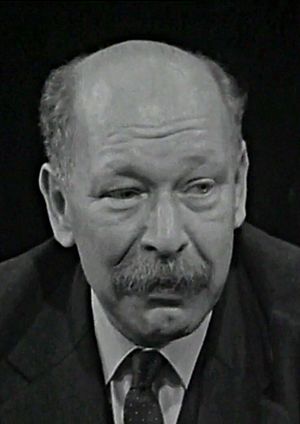

Photo of Éric Weil

|

Éric Weil (born June 4, 1904 – died February 1, 1977) was a French-German philosopher. He is known for his idea that understanding violence is a central part of philosophy. Weil saw himself as a follower of both Hegel and Kant, two very important philosophers. He helped bring new interest to their ideas in France during the 20th century.

Weil wrote many important books and essays in French, German, and English. He was a busy academic and also a public thinker. He took part in famous discussions, like those by Alexandre Kojève about Hegel's ideas. Weil also helped start and edit the journal Critique. Many of his students, like Bourdieu, said he greatly influenced their thinking. After his death, some of his former students created the Institut Éric Weil, a research center, to honor him.

Weil was a very organized thinker. His main ideas are found in his books: Logique de la philosophie (1950), Philosophie politique (1956), and Philosophie morale (1961). These books explain how trying to understand violence, by talking about it and giving it meaning, is the basis of philosophical thought. Weil believed that new forms of violence always appear. Because of this, he stressed that history is very important in philosophy. For example, in his political ideas, he thought that political groups often started from violent acts, like military leaders taking land.

Contents

Early life and education

Éric Weil was born on June 8, 1904, in Parchim, a town in Germany. His parents, Louis and Ida Weil, were from a wealthy Jewish family. He grew up in Parchim and went to school there. In 1922, he finished high school and went to Hamburg to study medicine. Soon after he started university, his father died. This caused financial problems for Weil's family throughout his student years.

Even while studying medicine, Weil was interested in philosophy. In 1922, he took a philosophy course with Ernst Cassirer. The next year, Weil moved to Berlin and continued his medical studies. For the next ten years, he moved between Hamburg and Berlin, studying philosophy full-time. He earned his doctorate under Cassirer, writing about Pietro Pomponazzi. During this time, he also published articles and worked as a private tutor. He became involved with the Warburg Library in Hamburg. In 1930, Weil moved back to Berlin and became the personal secretary to philosopher Max Dessoir. He also helped publish Dessoir's journal.

In 1932, Weil's doctoral paper was published. During this difficult time, he read Mein Kampf. Understanding the danger it posed to him as a Jew, he began looking for options outside Germany. He even applied for a job at the University of Puerto Rico, but did not get it.

Flight from Germany

In April 1933, Weil moved to Paris, France. There, he began a relationship with Anne Mendelsohn, a German Jewish immigrant and childhood friend of Hannah Arendt. Weil's first years in France were hard. He moved often and struggled with money. Despite this, he and Anne got married in Paris in October 1934, and then had a religious ceremony in Luxembourg a week later. Luxembourg became a meeting point for Weil and his relatives, as he refused to return to Germany for many years.

Even with the instability, Weil began to join the intellectual life in Paris. He became a French citizen. He continued his work on Renaissance humanism, studying thinkers like Marsilio Ficino and Plotinus. This work, which explored how they tried to combine Platonism and Christianity, was not published until 2007. Around this time, he started the work that would become Logique de la philosophie. This book explored how philosophical ideas and logical thinking shape history.

He also began working with Alexandre Koyré, to whom Logique de la philosophie was later dedicated. They collaborated on a journal from 1934 to 1938. Weil also attended Koyré's seminar on Hegel, which was later taken over by Alexandre Kojève. Koyré also supervised Weil's work on "The critique of astrology by Pic de la Mirandole," which helped him get an equivalent degree in France. Towards the end of the 1930s, events in Germany deeply affected Weil's family. His mother had to sell their family home. His sister Ruth's home was ransacked, and her husband was arrested. In 1939, Ruth and her husband sent their daughters to the Netherlands to hide. Only the husband and daughters survived the war, eventually moving to Australia.

War years

World War II deeply affected Weil, like many of his generation. As a German Jew, he felt the impact of the Nazi regime very strongly. The war also showed his philosophical, political, and personal beliefs. A change in his thinking had already begun before the war. This time in Paris marked the start of his ideas for Logique de la philosophie. Weil began to develop his theory about how basic philosophical ideas organize the world.

In this work, Weil set up a main conflict between liberty (freedom) and violence. He showed how logical thinking comes from the interaction of these two forces. For Weil, logical rationality is created when violence is understood and explained using the idea of contradiction. Weil's entire project aimed to understand how things get meaning (like actions, ideas, or feelings). This meaning could then help people overcome violence.

This was not just a theoretical idea for him. At the start of the war, Weil used a fake name, Henri Dubois, and joined the French army to fight the Nazi regime. In June 1939, he was taken prisoner and held at Fallingsbostel. There, he helped organize resistance among the prisoners and wrote for their secret newspaper. He remained a prisoner until 1945, when the camp was freed. He then returned to Paris.

Academic career

Back in Paris, Weil quickly got a job as a researcher at CNRS. Within a year, he finished writing Logique de la philosophie. He also reconnected with Georges Bataille, whom he had met in the Hegel seminars. This led to Weil's involvement with the journal Critique. During this time, he defended his doctoral thesis at the Sorbonne, using Logique de la philosophie and Hegel and the State as his main texts. His examiners included famous philosophers like Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Over the next few years, Weil was very active in Parisian philosophy. He organized conferences, took part in seminars, and wrote articles. He also started teaching at the École pratique des hautes études. He eventually became a Junior Professor at the University of Lille. At 52, Weil finally had a stable job. Over the next decades, he published his other two major books, Philosophie politique and Philosophie morale. He also published a book on Kant, Problèmes Kantiens, and two collections of his articles.

His reputation as a public intellectual grew. He published in international journals, gave many international talks, and was a visiting professor in the United States. In 1968, after 12 years in Lille, Weil took a job at the University of Nice. He and his wife moved to southern France. Weil remained active until his death on February 1, 1977, at his home in Nice. He gave his last lecture on Hegel just months before he died.

Recognition

During his life, Éric Weil was a well-known and respected public intellectual. He was chosen to participate in the UNESCO Symposium on Democracy, alongside thinkers like John Dewey. He also attended the famous meeting at Royaumont. This was one of the first times that analytic and continental philosophers met. Important figures like P. F. Strawson and W. V. Quine were also there.

Besides being chosen for such important discussions, Weil received many honors. In 1965, he was named a chevalier of the French Légion d'Honneur. In 1969, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Münster. In 1970, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1975, he became a member of the French Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques. Many journals and reviews also published special editions celebrating his work.

Philosophical work

Weil's philosophical work is often divided into his practical philosophy (about how we should act) and his theoretical philosophy (about how we understand the world). This division comes from Kant. His theoretical ideas are best seen in Logique de la philosophie. His practical ideas are in Philosophie politique and Philosophie morale. However, these two parts of his philosophy are actually very connected and influence each other.

The Logic of Philosophy

Weil's first major book, Logique de la philosophie, explores the theoretical side of his ideas. This book looks at how different philosophical discussions are connected and how ideas get meaning. It also tries to explain how understanding itself is possible. Weil shows that the main ideas, or "categories," that organize human life are very important. These categories help us make sense of the world.

Weil believed that philosophical discussions are historical responses to the problem of violence. In his book, he says that starting philosophy is always a choice. He highlights that we always have a choice between violence and discourse (talking and reasoning). This means a choice between violence and meaning, or violence and reasonable action. Weil's work explores how violence can be a complete rejection of meaning. But he also looks at violence that tries to force its own meaning, even if that meaning is harmful (like the idea of a "superior race"). This shows why universalizability is so important for Weil. It means that meaning should be structured in a way that applies to everyone and helps rational beings act reasonably.

The structure of Logique is important. Weil wrote the main part first, then added a long introduction that explains the whole work. One challenge in understanding Logique is figuring out Weil's exact position. He presents many different ways to view philosophy. He believed in pluralism, meaning many different viewpoints. He thought that when we start philosophy, we use bits and pieces of past philosophical ideas that have survived in history. These fragments show that philosophy tries to understand reality as a whole. But they also show that past attempts to create universal meaning were not enough.

This search for understanding and for universal meaning, by removing things that don't fit, shows how Weil thought about violence. To understand reality as a whole, even things that resist being explained must find a place in the discussion, including violence. Weil said that "it is language that brings out violence." He believed that humans, because they can speak and think, are the only ones who can see violence. This is because humans are the only ones who look for meaning in their lives and the world. To understand violence and overcome it, violence must be put into words. For Weil, violence enters discussion by being seen as a contradiction.

The introduction to Logique shows how different philosophical discussions came about and how they developed over time. Weil uses ideas from sociology and anthropology that are familiar to many. He starts by taking concepts like desire, satisfaction, reason, and violence as simple. But the introduction then shows how difficult it is to define things and how giving meaning to concepts is a complex task.

The rest of the book has 18 chapters, each about a different philosophical category. These categories include: Truth, Nonsense, The True and the False, Certainty, Discussion, The Object, The Self, God, Condition, Conscience, Intelligence, Personality, The Absolute, The Oeuvre, The Finite, Action, Meaning, and Wisdom. These categories represent historical philosophical discussions. Each category has three parts: the category itself (a clear explanation of an idea), the attitude (the unspoken way of living that leads to the idea), and the reprise (how an idea is understood in the language of another idea).

Categories

Weil made an important difference between two types of categories:

- Metaphysical categories: These are ideas developed by metaphysics (the study of basic reality) for use in specific sciences. They are fundamental concepts that help us understand what something is. For example, Aristotle's ideas of essence or attribute. These categories help guide scientific study, but they don't guide metaphysics itself.

- Philosophical categories: Weil was more interested in these. They are "constitutive of the philosophical discourse as an absolutely coherent discourse." This means they help create a completely logical philosophical discussion. Weil's categories, starting with Truth, don't try to match reality exactly. Instead, they define a certain "relationship to philosophizing," meaning how we talk about philosophy and make it logical.

The category of The Absolute is special. It is "the first category of philosophy." It moves Weil's project away from linking philosophy to ideas of Being or substance. Instead, it connects philosophy to the idea of meaning. Philosophical categories "no longer target the creation of philosophy as a science, they define a certain relationship to philosophizing." The idea of a completely logical discussion, found in The Absolute, means having the tools to overcome contradiction through language. This is because the question is about meaning, not just about what is real.

The categories after The Absolute explore how we relate to discussion. For example, The Oeuvre looks at rejecting discussion and meaning entirely. The Finite explores breaking down logical ideas. Action looks at making ideas real. And Meaning and Wisdom reflect on the role of discussion and how individuals relate to it. This is why choosing philosophy, which means choosing logical thinking, is a fundamental choice. It's a choice made to overcome violence.

Attitudes

Weil called the unspoken background of ideas that guides a person's actions an "attitude." This background is organized around a main idea, but it hasn't been clearly put into words yet. Attitudes are often mixed and can be "ambiguous and contradictory." An attitude is a practical way of living that doesn't necessarily need to solve contradictions, as long as life continues. It's also the basis for categories, as it represents the unspoken practices that categories then explain as a clear idea or "doctrine."

As Marcelo Perine noted, "it is the category that determines the purity and the irreducibility of the attitude, but it is the attitude that produces the category." This means the category explains the attitude, but only after the category itself is fully developed. The philosopher who explains an attitude by making its ideas logical has already gone beyond that attitude. Because an attitude is built around a concept that organizes human activity, that activity cannot be fully understood from within the concept itself. Weil believed that philosophy is born from the need to reorganize a world that no longer makes sense. So, the person who can logically explain the world has already moved past the old ideas. Humanity always finds itself in a historical tradition. Therefore, the question of how to give meaning and understand the world always comes up again. Weil asked, "Attitudes, both unconscious and without category, do they not direct, ordinarily, life?"

Reprises

The connections between categories and attitudes, and all the bits of past attempts to overcome violence through clear discussions, are linked by what Weil called "reprisals." A reprise is "first off an interpretive act." This act works in two ways. First, it's how an older category tries to understand a new attitude using its own language, which isn't quite right for the new idea. Second, it's how the new attitude explains itself using the language of other attitudes and categories.

In this way, the reprise helps connect philosophy and history. However, because a reprise uses other discussions to explain something that doesn't quite fit, it helps us understand the many different centers of discussion that exist in human experience. Categories are like a clear form of life that is actually lived as an attitude. The reprise helps explain the different parts of this form of life, and the different beliefs (like religious or political ones) held by people within it.

Moral philosophy

Weil's moral philosophy is about how we should act. It is a deeper look into the idea of "conscience." Following Kant, Weil tried to explain how "nature and freedom" exist together. To do this, Weil separated formal morality from concrete morality.

- Formal morality is the philosophical study of universal moral rules, like those from Kant, and the idea of autonomy (self-rule). This leads to thinking about rules, starting with the "rule of the universalization of maxims." This step is needed when people lose faith in concrete morality.

- Concrete morality is the morality of a community that used to provide those rules.

There is a constant tension between community rules and the need to make moral ideas universal. For Weil, moral action happens when different moralities meet. This forces people to think about their own moral system. From this thought, a person faces a moral choice, decided by what can be made universal. Weil's moral theory emphasizes how people become aware of universal rules, so they can see themselves as the source of moral law.

One big difference between Weil and Kant is that for Weil, realizing moral law and becoming aware of oneself as a moral agent is only a possibility. Any person, in any historical situation, might never become aware of their role as a moral agent. This led Weil to say that "the essential task of the moral man is to educate men so that they obey on their own the universal law." Education is very important in Weil's philosophy. The highest goal of moral and political action is to lead people to reason, so they can become reasonable themselves.

The connection between logical thinking, universal rules, and being reasonable defines moral action. This means moving from moral law to a moral life. Ideas like happiness, satisfaction, desire, or duty get new, clearer meanings. To do this, "it is necessary to take a further step and consider morality as a relation to others, in the context of a concrete morality." This step leads directly to Weil's political thought.

For Weil, political action is about our responsibility to others. This turns the need for universal rules into a discussion about justice. Justice means both equality and legality. It requires bringing together universal ideas and actual laws, which might sometimes prevent universal ideas from happening. So, justice demands a critical look at a community's laws to make them fair.

Political philosophy

Weil's political philosophy builds on his theoretical ideas. His book Philosophie politique expresses the philosophical category of Action. The categories after The Absolute are about "a revolt against coherence." They respond to individual action when faced with the idea of complete logical thinking. The category of The Oeuvre shows that it's possible to reject discussion. This is because "the language of the man of […] [this category] does not make a claim to universality or to truth. It is the language of an individual who wants to control the world." This category is partly Weil's response to the possibility of totalitarian violence, which caused so much destruction in the 20th century.

Weil's political philosophy is influenced by thinkers like Aristotle, Kant, Hegel, and Marx. But he focused on the real-life aspects of human experience. For Weil, the goal of logical thinking must constantly restart, and it always risks being broken by new forms of violence. Weil said that Action is "the last category of discourse." In this category, human activity is seen as "the unity of life and discourse." This means it gives new, real meaning to both actual human attitudes and to the ideas that explain that activity.

All of Weil's political thought starts from the individual's point of view, from the moral question of freedom. This leads to thinking about how political groups are organized. This organization should be understood naturally, like his ideas about social groups and the relationship between community and civil society. This natural development of communities, and their often difficult interactions with civil society, also leads to a theory of the State.

The need for justice helps expand the moral need for universal rules into a full political need. It also means that modern society must provide a way for individuals' goals and projects to have meaning. This need for meaning connects political activity back to Weil's larger goal of logical thinking. This is because only within an organized State can this need for meaning be met.

This return to the theoretical side of Weil's ideas shows the importance of discussion in his practical philosophy. For Weil, choosing philosophy (choosing logical thinking) is a choice made to overcome violence by giving it a clear form. For that logical thinking to be a real expression of meaning, individuals must become aware of their ideas through open discussion. In this way, discussion becomes a serious form of political action. Weil believed that "acting is deciding after having deliberated." Only through open discussion can conflicts and problems be brought out into the open. Then, they can be solved through political compromises that bring different social groups together based on justice.

This idea of justice gives a voice to the many different goals, needs, struggles, and values within a political group. The historical and changing content of these ideas comes from the natural development of the State. Weil defined the State as "the organic set of institutions of a historic community." In Philosophie politique, Weil looks at the State from many angles. He analyzes the modern State, which is based on a "formal and universal" idea of law. He also looks at different forms of political organization, from dictatorships to constitutional governments.

Underlying these analyses is a defense of constitutional democracy. In this system, "each citizen is considered as a potential ruler, and not only as ruled." This means that all citizens have the ability and right to be in decision-making positions. It also means that decisions should be made through open, public discussions involving everyone. In this sense, and because of his general idea of universalizability, Weil believed that understanding and overcoming violence leads to a form of cosmopolitanism. This means that as society becomes more global, it will lead to a global form of political organization. This global structure of States would allow individuals to truly experience freedom. It would give a voice to their unique qualities and those of their community. In this way, a global structure connects back to Weil's main goal: to explain how action and discussion are united. For Weil, human activity and history itself gain meaning within political organization. Political organization is the setting where moral action is possible, and where an individual's life can be given concrete meaning.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Eric Weil para niños

In Spanish: Eric Weil para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |