Maurice Merleau-Ponty facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

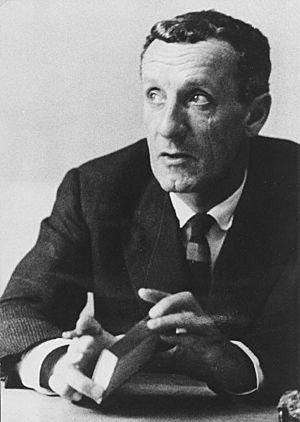

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Maurice Jean Jacques Merleau-Ponty

14 March 1908 Rochefort-sur-Mer, Charente-Inférieure, France

|

| Died | 3 May 1961 (aged 53) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure, University of Paris |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Phenomenology Existential phenomenology Embodied phenomenology Western Marxism Structuralism Post-structuralism |

|

Main interests

|

Aesthetics · anthropology · consciousness · embodiment · · meaning · ontology · perception · politics · psychology |

|

Notable ideas

|

Invagination, Gestalt, anonymous collectivity, motor intentionality, the flesh of the world, incarnation, chiasm (chiasme), speaking vs. spoken language, institution |

|

Influences

|

|

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (born March 14, 1908 – died May 3, 1961) was a French philosopher. He was very interested in how people make sense of the world through their experiences. He wrote about many topics like perception, art, politics, language, and psychology.

Merleau-Ponty believed that our perception of the world is super important. He thought that how we experience things is a constant conversation between our body and the world around us. He was one of the few major philosophers of his time who also paid close attention to science. His ideas have influenced how philosophers connect their thoughts with psychology and cognitive science.

He stressed that our body is the main way we understand the world. This was different from older ideas that said our consciousness was the only source of knowledge. Merleau-Ponty believed that our perceiving body and the world we perceive are always connected. He called this idea the "flesh of the world."

Merleau-Ponty also thought a lot about Marxism, which is a political and economic theory. In his book Humanism and Terror, he explored the difficult question of how to achieve good human values in politics. He wondered if sometimes strong actions are needed, and how to decide what is fair. He remained interested in Marxist ideas throughout his life, even though he didn't always agree with everything.

Life of Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Merleau-Ponty was born in 1908 in Rochefort-sur-Mer, France. His father passed away when Maurice was five years old. He went to school in Paris and later studied at the École Normale Supérieure. There, he met other famous thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

In 1929, he earned his master's degree from the University of Paris. He then became a philosophy teacher in 1930. Merleau-Ponty was raised as a Roman Catholic. However, he left the Catholic Church in 1937 because he felt his socialist political beliefs didn't fit with the Church's teachings.

Some recent discoveries suggest that Merleau-Ponty might have written a novel called Nord. Récit de l'arctique in 1928, using the pen name Jacques Heller.

He taught at different schools before becoming a tutor at the École Normale Supérieure in 1935. He earned his doctorate with two important books: La structure du comportement (1942) and Phénoménologie de la Perception (1945). During this time, he learned about Hegel's philosophy and Gestalt psychology.

In 1939, he visited the Husserl Archives to study unpublished writings. When France declared war on Nazi Germany, he served in the French Army and was injured. After returning to Paris, he married Suzanne Jolibois, a psychoanalyst. He also helped start an underground resistance group with Jean-Paul Sartre. He even took part in a protest against the Nazi forces during the liberation of Paris.

After the war, he taught at the University of Lyon and then at the Sorbonne. In 1952, he became a professor at the Collège de France, which was a great honor. He was the youngest person ever chosen for that position.

Besides teaching, Merleau-Ponty was also the political editor for a leftist magazine called Les Temps modernes. He worked there from 1945 to 1952. He was interested in Karl Marx's ideas, and some say he even introduced Sartre to Marxism. He wrote a book called Humanism and Terror in 1947, where he explored complex political ideas. Later, he changed some of his views on politics, which led to the end of his friendship with Sartre.

Merleau-Ponty died suddenly in 1961 at age 53 from a stroke. He was working on a new book, The Visible and the Invisible, which was published after his death. He is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Merleau-Ponty's Ideas

Understanding Consciousness

In his book Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty talked about the idea of the "body-subject." This means that our body is not just a thing, but also a way we experience and know the world. He believed that our consciousness, the world, and our body are all deeply connected.

He thought that the things we perceive are not just fixed objects. Instead, they are connected to our body and how we use our senses. Our body actively understands things in the world, even before we think about them. He said that our understanding of things is always growing and changing.

Merleau-Ponty also believed that we only see things from a certain angle or at a certain time. But this doesn't make them less real. In fact, it's how things become real to us. Everything we see is connected to its background and other objects around it. He said that each object is like a "mirror of all others."

The Importance of Perception

Merleau-Ponty wanted to show that perception isn't just about simple feelings or sensations. He believed that perception is an active way we connect with the world around us. He called this the "primacy of perception."

He studied the writings of Edmund Husserl, another philosopher who influenced him. Husserl said that "all consciousness is consciousness of something." This means there's a difference between our thoughts and the things we think about. But Merleau-Ponty found that some experiences, like our body, time, or other people, don't fit neatly into this idea.

So, Merleau-Ponty suggested that "all consciousness is perceptual consciousness." This means that our ability to perceive is the most basic way we understand the world. This idea changed how people thought about phenomenology, a way of studying experience.

The Body and Experience

Because he focused on perception, Merleau-Ponty realized that our own body is not just an object. It's also how we experience everything. He emphasized that our consciousness and our body are always linked.

He disagreed with René Descartes, an older philosopher who thought the mind and body were completely separate. Merleau-Ponty believed that our body has its own way of understanding and acting in the world, even without us consciously deciding. He wrote: "As long as I have hands, feet, a body, I have intentions around me that don't depend on my decisions."

Understanding Space

Merleau-Ponty also thought about how our body helps us understand space. He believed that the idea of "depth" is very important in how we experience being in the world. Our body helps us make sense of where we are and how things relate to each other in space. These ideas are also important in architectural theory, which studies how buildings and spaces are designed.

Language and Expression

Merleau-Ponty explored how our body's ability to express itself is key to how we develop our sense of self. He looked at how people use actions that go beyond just physical movements, like thinking and creating culture.

He paid special attention to language as the center of culture. He studied how thoughts and meanings develop through language. He also looked at how language problems, painting, movies, books, poetry, and music all show how we express ourselves.

He continued to study how children learn language and how the ideas of Ferdinand de Saussure in linguistics could help understand this. He also explored the idea of "structure" in psychology, linguistics, and social anthropology.

Art and Style

Merleau-Ponty talked about two types of expression: primary and secondary. Secondary expression is like the language we already know, our cultural background. Primary expression is when language creates a new meaning, when a thought is just forming.

He was most interested in primary expression, or "speaking language." This is language as it creates new sense. He looked at how we create and understand expressions, connecting it to actions, intentions, and perception.

The idea of style was important to him, especially in art. He thought that style comes from how different parts of the world interact. He believed that our consciousness comes from the "pre-conscious style" of the world and nature.

Science and Perception

In his essay Cézanne's Doubt, Merleau-Ponty compared science to art. He saw art as trying to capture an individual's perception. But he saw science as being against individual views.

In his book Phenomenology of Perception, he argued that science can't tell us everything about human experience. He felt that science often explains things by looking at them after they've happened, rather than understanding the direct experience itself. He believed that science sometimes misses the deep and rich meaning of the things it tries to explain.

Merleau-Ponty wanted to connect science back to direct experience. He wanted science to "return to the phenomena," meaning to focus on how things appear to us in our lived experience.

Influence of Merleau-Ponty

New Ideas in Cognitive Science

Even though Merleau-Ponty was critical of some scientific views, his work has influenced modern psychology and cognitive science. His ideas helped create a field called "post-cognitivism."

Philosophers like Hubert Dreyfus have shown how Merleau-Ponty's ideas are important for understanding how our bodies and actions are key to thinking, not just our brains. This led to new ways of thinking about how computers and minds work.

His work also influenced "embodied cognition," which says that our thoughts are shaped by our bodies and how they interact with the world. This field also led to "neurophenomenology," which tries to combine brain science with the study of experience.

Feminist Philosophy

Merleau-Ponty's ideas have also been used by feminist philosophers. For example, Iris Marion Young used his ideas to study how women move and experience their bodies differently from men.

In her essay "Throwing Like a Girl," Young observed that women often move in a more careful way, while men might use their whole body more freely. She connected this to Merleau-Ponty's idea that we experience the world based on what our bodies "can do." Young suggested that for women, this feeling of "I can" might sometimes be held back.

Ecophenomenology

Ecophenomenology is a field that looks at how humans and other creatures connect with the world around them. It's about the relationship between living things and their environment.

This field sees a connection that is not just about objects or just about individual feelings. It's a space where living things interact with the world in a material way. In this way, phenomenology can connect with naturalism, which studies nature.

David Abram explained Merleau-Ponty's idea of "flesh" as the "mysterious tissue" that connects both the person who perceives and the thing being perceived. Abram linked this idea to the interconnected web of life on Earth. This means that the subject (us) and the object (the world) are part of a deeper reality. Merleau-Ponty called this "the flesh," and Abram called it "the animate earth" or "the breathing biosphere." This is not just nature as a collection of objects, but nature as it is experienced by our intelligent bodies.

Merleau-Ponty himself said that "language is the very voice of the trees, the waves and the forest." He also wrote that nature is like "the other side of humanity," not just as matter, but as "flesh." This shows how deeply he felt about the connection between humans and the natural world.

See also

In Spanish: Maurice Merleau-Ponty para niños

In Spanish: Maurice Merleau-Ponty para niños

- Gestalt psychology

- Process philosophy

- Embodied cognition

- Enactivism

- Difference (philosophy)

- Virtuality (philosophy)

- Field (physics)

- Hylomorphism

- Autopoiesis

- Emergence

- Umwelt

- Habit

- Body schema

- Affordance

- Perspectivism

- Reflexivity

- Invagination (philosophy)

- Incarnation

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |