Max Scheler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

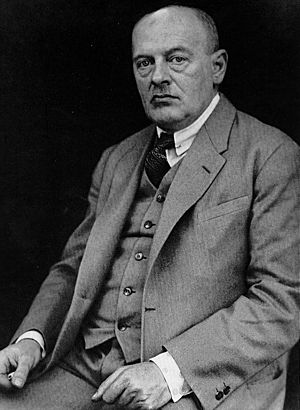

Max Scheler

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Max Ferdinand Scheler

22 August 1874 |

| Died | 19 May 1928 (aged 53) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Phenomenology Munich phenomenology Ethical personalism |

| Doctoral students | Hendrik G. Stoker |

|

Main interests

|

History of ideas, value theory, ethics, philosophical anthropology, consciousness studies, sociology of knowledge, philosophy of religion |

|

Notable ideas

|

Value-ethics, stratification of emotional life, ressentiment, ethical personalism |

|

Influenced

|

|

Max Ferdinand Scheler (born August 22, 1874 – died May 19, 1928) was a German philosopher. He is famous for his ideas on phenomenology, ethics, and what it means to be human (called philosophical anthropology).

During his life, many people thought Scheler was one of Germany's most important philosophers. He built upon the ideas of Edmund Husserl, who started phenomenology. Another philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, even called Scheler the "Adam of the philosophical paradise."

After Scheler passed away in 1928, Martin Heidegger said that all philosophers of that century owed a lot to Scheler. He called him "the strongest philosophical force in modern Germany."

Scheler's ideas also greatly influenced Pope John Paul II. The Pope wrote his doctoral paper in 1954 about Scheler's philosophy. Because of this, and because Scheler taught Edith Stein, his ideas are still important in Catholic thinking today.

Contents

Max Scheler's Life and Work

Growing Up

Max Scheler was born in Munich, Germany, on August 22, 1874. His family was Jewish and well-respected. As a teenager, he became interested in Catholicism. Important Catholic thinkers like St. Augustine and Pascal later shaped his philosophical views.

Student Days

Scheler first studied medicine at the University of Munich. He then switched to the University of Berlin to study philosophy and sociology. There, he learned from famous thinkers like Wilhelm Dilthey and Georg Simmel.

In 1896, he moved to the University of Jena. He studied with Rudolf Eucken, a very popular philosopher who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1908. Scheler finished his doctorate degree in 1897. His paper was about how logical and ethical rules are connected. In 1898, he met Max Weber, another important thinker who influenced him. Scheler became a lecturer at the University of Jena in 1901.

Early Career and World War I

Scheler taught at Jena from 1901 to 1906. Then he moved to the University of Munich, teaching there from 1907 to 1910. During this time, he studied Edmund Husserl's phenomenology in depth. Scheler had met Husserl in 1901.

At Munich, Scheler joined the Phenomenological Circle. This was a group of philosophers who discussed Husserl's ideas. Scheler was never a direct student of Husserl's, and they sometimes disagreed.

In 1910, Scheler lost his teaching job in Munich due to a conflict between the university and local media. He then lectured briefly in Göttingen, where he met other important philosophers like Edith Stein. Stein was one of his students and was very impressed by him. In 1911, he moved to Berlin and became a writer.

Scheler's first marriage ended, and he married Märit Furtwängler in 1912. She was the sister of the famous music conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler.

In 1912, Scheler helped start a famous philosophy journal called Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung. His first major book, Zur Phänomenologie und Theorie der Sympathiegefühle und von Liebe und Hass (later translated as The Nature of Sympathy), came out in 1913. It was strongly influenced by phenomenology.

During World War I (1914–1918), Scheler was first called to serve in the army but was later excused due to an eye problem. He strongly supported Germany's efforts in the war.

Later Years in Cologne

In 1919, Scheler became a professor of philosophy and sociology at the University of Cologne. He taught there until 1928.

After 1921, he publicly moved away from Catholic teachings. He became interested in pantheism (the idea that God is everything) and philosophical anthropology (the study of what makes humans unique).

His ideas also became more political. He was one of the few scholars in Germany at the time who publicly warned about the dangers of National Socialism (Nazism) and Communism. He met the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev in 1923. In 1927, he gave talks about 'Politics and Morals'.

Scheler believed that capitalism was not just an economic system. He saw it as a way of thinking that makes people constantly seek security and control. He thought this mindset could make people less important. Instead, Scheler called for a new era of culture and values.

He also supported the idea of a "United States of Europe" and international universities. He worried about the gap in Germany between political power and mind (intellectual thought). He saw this gap as a major reason for a coming dictatorship and a barrier to German democracy. Five years after his death, the Nazi government (1933–1945) banned Scheler's work.

Towards the end of his life, Scheler received many invitations from countries like China, India, and Japan. He had to cancel a trip to the United States due to health reasons.

In 1927, Scheler gave a long lecture called 'Man's Particular Place'. It was later published as Die Stellung des Menschen im Kosmos (Man's Position in the Cosmos). His powerful speaking style kept the audience interested for about four hours.

In early 1928, he accepted a new job at the University of Frankfurt. He looked forward to discussing ideas with other thinkers there.

Scheler smoked a lot, which led to several heart attacks in 1928. He died on May 19, 1928, in a Frankfurt hospital from a severe heart attack. He had planned to publish a major book on anthropology in 1929, but his early death stopped him.

Max Scheler's Philosophical Ideas

Love and the "Phenomenological Attitude"

When asked to write about phenomenology, Scheler said it wasn't just a strict method. Instead, he described it as "an attitude of spiritual seeing." He believed it helps us see things that usually stay hidden.

For Scheler, phenomenology is about directly experiencing things. It's not like a scientific observation where the object stays still. The philosopher's attitude is very important for understanding these experiences. This attitude, he said, is based on love.

Scheler believed that philosophical thinking is "a love-determined movement." He thought that to truly understand the world, we need to approach it with love.

Love is important for philosophy for two main reasons:

- If philosophy is about understanding the "primal essence" of everything, then we need to share in the movement of love to connect with it.

- Love helps us see the highest possible value in things. When we truly love something, it's like our "spiritual eyes" open to its higher values. Hate, on the other hand, closes us off from seeing values.

Scheler called love and hate "spiritual feelings." He said they are the basis for how we understand values. Love helps us recognize values, just as our minds help us understand ideas.

Understanding Values: Material Value-Ethics

A key part of Scheler's philosophy is his idea that values are real and can be "felt." He disagreed with philosopher Immanuel Kant, who thought values were only formal rules. Scheler believed values are given to us directly, and we can feel them. The feeling of love helps us discover these values.

Values are not just abstract ideas; they exist with the things that carry them. For example, the value of a piece of art might change depending on the culture, but the idea of beauty itself remains a spiritual value.

Scheler said that understanding the value of something happens before we even think about it. We feel its value first, and then we can understand how different values connect.

He created a ranking of values, from highest to lowest:

- Religious values: Like holy or unholy.

- Spiritual values: Such as beauty or ugliness, knowledge or ignorance, right or wrong.

- Vital values: Like health or sickness, strength or weakness.

- Sensible values: Such as pleasant or unpleasant, comfort or discomfort.

Scheler also explained how good and evil relate to values:

- Doing something that brings about a positive value is good.

- Doing something that brings about a negative value (a disvalue) is evil.

- Choosing a higher value is good.

- Choosing a lower value instead of a higher one is evil.

He argued that being good comes from a person's basic moral character, not just from following rules.

Scheler believed that many older ethical systems made a mistake by focusing on only one type of value. He also introduced the idea of the "kairos," or the "call of the hour." This means that in difficult life choices, simple rules might not be enough. Our moral character helps us make ethical decisions.

A "disorder of the heart" happens when someone chooses a lower value over a higher one.

Scheler's ideas about values were unique. He believed that values can only be felt, just like colors can only be seen. Our minds can only organize values after we have experienced them. For Scheler, each person is where value experiences happen. His ideas about the "lived body" influenced other philosophers like Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Scheler also thought that the scientific method itself should be examined. He believed that true understanding comes from a deeper spiritual practice, not just from logical steps.

Man and History (1924)

Scheler had planned to publish a major work on what it means to be human in 1929, but he died before finishing it. In his 1924 book, Man and History (Mensch und Geschichte), he shared some early ideas about philosophical anthropology.

In this book, Scheler argued that we need to clear away all old ideas about humans that come from religion, philosophy, and science. He said it's not enough to just reject these traditions, like Nietzsche did by saying "God is dead." These traditions have shaped our culture so deeply that they still influence how we think, even if we don't believe in them. To truly be free, we need to study and understand how these ideas were built.

Scheler believed that philosophical anthropology should look at the whole person. It should also use information from specialized sciences like biology, psychology, and sociology.

Max Scheler's Writings

- Zur Phänomenologie und Theorie der Sympathiegefühle und von Liebe und Hass (On the Phenomenology and Theory of Sympathy and of Love and Hate), 1913

- Der Genius des Kriegs und der Deutsche Krieg (The Genius of War and the German War), 1915

- Der Formalismus in der Ethik und die materiale Wertethik (Formalism in Ethics and Non-Formal Ethics of Value), 1913 - 1916

- Vom Umsturz der Werte (On the Overthrow of Values), 1919

- Vom Ewigen im Menschen (On the Eternal in Man), 1921

- Wesen und Formen der Sympathie (The Nature of Sympathy), 1923

- Die Wissensformen und die Gesellschaft (Forms of Knowledge and Society), 1926

- Die Stellung des Menschen im Kosmos (Man's Place in the Cosmos), 1928

See also

In Spanish: Max Scheler para niños

In Spanish: Max Scheler para niños

- Axiological ethics

- Ressentiment (Scheler)

- Mimpathy