Gaston Bachelard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

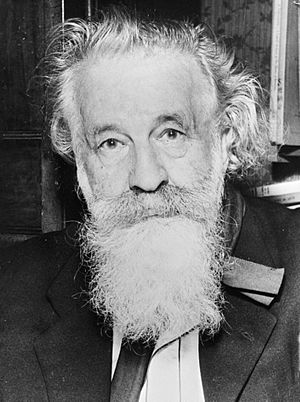

Gaston Bachelard

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 27 June 1884 Bar-sur-Aube, France

|

| Died | 16 October 1962 (aged 78) Paris, France

|

| Education | University of Paris (B.A., 1920; D.-ès-Lettres, 1927) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy French historical epistemology |

| Institutions | University of Dijon University of Paris |

| Doctoral advisor | Abel Rey Léon Brunschvicg |

|

Main interests

|

Historical epistemology constructivist epistemology, history and philosophy of science, philosophy of art, phenomenology, psychoanalysis, literary theory, education |

|

Notable ideas

|

Epistemological break, the poetics of space, rational materialism, technoscience (techno-science) |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Gaston Bachelard (born June 27, 1884 – died October 16, 1962) was a French philosopher. He made important contributions to poetics (the study of poetry) and the philosophy of science. In the philosophy of science, he introduced ideas like the epistemological obstacle and the epistemological break. These ideas explain how scientific progress can be blocked or how big changes happen in scientific thinking.

Bachelard's work influenced many later French thinkers. These include famous philosophers like Michel Foucault and Louis Althusser, and sociologists such as Pierre Bourdieu.

For Bachelard, scientific knowledge is always being built and improved. It's not something fixed. He believed that experience (learning from what we see) and reason (learning through thinking) work together. They are not opposites. So, both a priori (knowledge before experience) and a posteriori (knowledge after experience) are important for scientific research.

Contents

Gaston Bachelard's Life and Work

Gaston Bachelard started his career as a postal clerk in Bar-sur-Aube, France. Later, he studied physics and chemistry. Eventually, he became very interested in philosophy.

In 1927, he earned his doctorate degree. He wrote two main papers for this. One was about how we get to know things, and the other was about how heat travels in solid objects.

He first taught in 1902, but then he thought about working in telegraphy. Even though he loved literature, he chose to study technology. He then moved towards science and mathematics. He was especially fascinated by the big discoveries of his time. These included radioactivity, quantum mechanics, relativity, and wireless telegraphy.

From 1930 to 1940, Bachelard was a professor at the University of Dijon. After that, he became a professor at the University of Paris. There, he taught about the history and philosophy of science. In 1958, he became a member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium.

Understanding the Scientific Mind

Bachelard studied the history and philosophy of science. He wrote books like "The New Scientific Spirit" (1934) and "The Formation of the Scientific Mind" (1938). He saw the study of how knowledge develops (called epistemology) as a way to understand the scientific mind. It was almost like a psychoanalysis for how scientists think.

Bachelard showed that certain ways of thinking can actually stop science from moving forward. He called these obstacle épistémologique, or "epistemological obstacles." One goal of studying epistemology is to help scientists see these mental blocks. This way, they can overcome them and gain new knowledge.

Big Changes in Science: Epistemological Breaks

Bachelard disagreed with thinkers like Auguste Comte. Comte believed that science always progressed smoothly and continuously. Bachelard, however, saw that scientific history had many sudden changes. For example, Albert Einstein's theory of relativity completely changed how we understood space and time. This showed that science doesn't always move forward in a straight line.

Bachelard used the idea of an "epistemological break" to highlight these big shifts in science. This term became very famous through the work of Louis Althusser.

He explained that new scientific theories don't just add to old ones. They often create new ways of thinking, or "paradigms." This can change the meaning of old concepts. For instance, the idea of mass meant different things to Newton and Einstein. New ideas, like non-Euclidean geometry, didn't prove Euclidean geometry wrong. Instead, they included it in a much bigger and more complex system.

Bachelard as a Teacher and Philosopher

After serving in the military, Bachelard became a physics and chemistry teacher in Bar-sur-Aube in 1919. He married Jeanne Rossi, a schoolteacher, in 1914. Their daughter, Suzanne, was born in 1919. Sadly, Jeanne died in 1920, and Bachelard raised Suzanne by himself.

At 36, he began an unexpected career in philosophy. He earned his Doctor of Letters degree from the Sorbonne in 1927. His important papers were published. He became a lecturer at the University of Dijon in 1927. He continued to teach in Bar-sur-Aube until 1930. He even took part in local elections to support the idea of a college for everyone. He accepted a professorship at the University of Burgundy when his daughter Suzanne started her secondary education.

He did the same when he was appointed a university professor at the Sorbonne in 1940. He became the director of the Institute for the History of Science and Technology. He wanted to support his daughter's higher education.

In 1937, he was honored as a Knight of the Legion of Honor. He taught at the Sorbonne from 1940 to 1954. He held the important position of chair of the history and philosophy of science.

The Role of Epistemology in Science

Bachelard was a rationalist, meaning he believed in the power of reason. He thought that "scientific knowledge" was different from everyday knowledge. He saw mistakes in science not as complete failures, but as steps towards finding the truth. He said that "scientifically, one thinks truth as the historical correction of a persistent error."

The job of epistemology is to show how scientific concepts are created over time. These concepts are not just ideas; they are also practical. They are part of how we use technology and how we teach. For example, an electric light bulb is an object of scientific thought. To understand how it works, you need scientific knowledge. So, epistemology helps us understand the history of how these scientific ideas and objects came to be.

How Scientific Views Change

Bachelard believed that modern science had moved away from thinking about things as fixed "substances." Instead, it focused on "relations" or how things interact. For example, in classical philosophy, matter and movement were seen as separate. But modern science shows that matter and rays (like light) cannot be separated.

In Bachelard's view, there are no simple, basic "substances" as some older philosophies believed. Instead, scientific objects are complex. They are built through theories and experiments and are always being improved. This led Bachelard to support a kind of constructivist epistemology. This means he believed that knowledge is actively built by us, rather than just discovered.

Other Academic Interests

Besides epistemology, Bachelard also explored many other topics. These included poetry, dreams, psychoanalysis, and the imagination. His books The Psychoanalysis of Fire (1938) and The Poetics of Space (1958) are among his most well-known works. The Poetics of Space has been very influential in architectural theory and continues to be important in literary studies.

See also

In Spanish: Gaston Bachelard para niños

In Spanish: Gaston Bachelard para niños

- Constructivist epistemology

- Epistemological psychology

- Ophelia complex

- Suzanne Bachelard

- Thomas S. Kuhn

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |