Max Weber facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Max Weber

|

|

|---|---|

Weber in 1918

|

|

| Born |

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber

21 April 1864 |

| Died | 14 June 1920 (aged 56) |

| Alma mater | |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Levin Goldschmidt |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

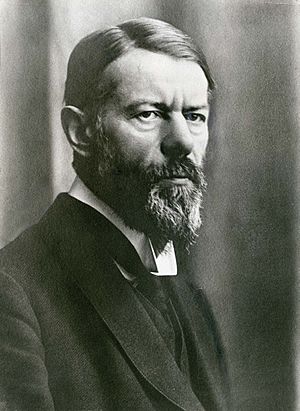

Max Weber (born April 21, 1864 – died June 14, 1920) was a very important German thinker. He was a sociologist, historian, lawyer, and economist. Many people see him as one of the most important thinkers about how modern Western society developed.

Weber's ideas greatly changed how we understand society and how we study it. He is known as one of the "fathers of sociology," along with Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim. Even though he didn't call himself a sociologist, his work shaped the field.

Unlike some other thinkers, Weber believed that many things can cause an outcome, not just one. He also thought that to understand social actions, you need to look at what people think and feel. This is called Verstehen, which means "to understand" in German.

Weber was very interested in how society became more organized and logical, a process he called "rationalization." He also studied how religion lost its magical feel, which he called "disenchantment." He believed these changes were linked to the rise of capitalism and modern life.

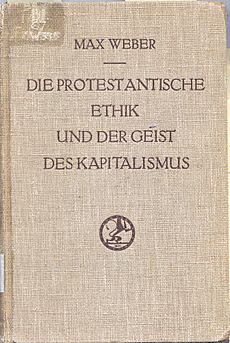

One of his most famous ideas is about how certain religious beliefs, especially Protestantism, helped capitalism grow. He wrote about this in his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. He also studied other religions like those in China and India to see how they affected society and economics.

Weber also defined the "state" as the only group that can legally use physical force within a certain area. He also came up with three types of authority: charismatic (based on a leader's special qualities), traditional (based on old customs), and rational-legal (based on rules and laws). He showed that modern organizations often rely on rational-legal authority, like in a bureaucracy.

After World War I, Weber helped start the liberal German Democratic Party. He also advised on writing the Weimar Constitution, which was Germany's democratic constitution. He died in 1920 at age 56 from pneumonia, after getting the Spanish flu.

Contents

- About Max Weber's Life

- Max Weber's Career and Later Life

- How Max Weber Studied Society

- Max Weber's Key Theories

- Max Weber's Economic Ideas

- Who Inspired Max Weber?

- Max Weber's Lasting Impact

- Criticisms of Weber's Ideas

- His Major Works

- See also

About Max Weber's Life

His Early Years

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber was born on April 21, 1864, in Erfurt, Prussia. His family moved to Berlin in 1869. He was the oldest of eight children.

His father, Max Weber Sr., was a lawyer and politician. His mother, Helene Fallenstein, came from a wealthy family and was a very religious Calvinist. Young Max saw the differences between his parents. His father enjoyed life's pleasures, while his mother was strict and focused on moral ideas.

Their home was full of discussions about politics and academics. Scholars and public figures often visited. Max and his brother Alfred, who also became a sociologist, grew up in this smart environment. When Max was 13, he wrote two history essays as Christmas gifts for his parents.

Even though he was bored in school, Weber secretly read many books, including all 40 volumes by the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Before university, he read many other important works, like those by the philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Starting His Academic Journey

In 1882, Weber began studying law at the University of Heidelberg. He later studied at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin and the University of Göttingen. While studying, he also worked as a junior lawyer and teacher.

In 1889, he earned his law doctorate. His paper was about the history of law. Two years later, he wrote another important paper that allowed him to teach at the university. He joined the faculty at Friedrich Wilhelm University, where he taught, researched, and advised the government.

During his university years, Weber also spent time in the military. After a few years of enjoying student life, he started to side more with his mother in family arguments. He grew apart from his father.

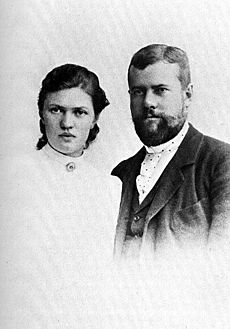

His Marriage

In 1893, Weber married his distant cousin, Marianne Schnitger. Marianne later became a feminist and writer. She was very important in gathering and publishing Max's writings after he died. Her book about his life is a key source for understanding him. They did not have any children. Marriage gave Weber the financial freedom to leave his parents' home.

Max Weber's Career and Later Life

Early Career Work

After finishing his studies, Weber became interested in social issues. In 1888, he joined a group of German economists who wanted to solve social problems. They studied economic issues using statistics. He also got involved in politics.

In 1890, Weber led a study on the "Polish question." This was about Polish farm workers moving into eastern Germany. His report got a lot of attention and made him known as a social scientist.

From 1893 to 1899, Weber was part of a group that was against the influx of Polish workers. Scholars still debate how much he supported German nationalist policies. In some of his talks, he criticized the immigration of Poles.

In 1894, Weber became a professor of economics at the University of Freiburg. In 1896, he moved to the University of Heidelberg. There, he became a key figure in the "Weber Circle," a group of smart people including his wife, Marianne. His research at this time focused on economics and legal history.

Dealing with Health Challenges

In 1897, Weber's father died after a big argument with Max that was never resolved. After this, Weber became very depressed and had trouble sleeping. This made it hard for him to teach. He had to stop teaching in 1899.

He spent time in a special hospital in 1900. Then he and Marianne traveled to Italy. He didn't return to teaching until 1919. His wife destroyed a personal diary that described his mental health struggles. She might have feared it would harm his reputation later.

Later Works and Ideas

After his health issues, Weber didn't publish much between 1898 and 1902. He left his professorship in 1903. This allowed him to focus on deeper social science questions. In 1904, he started publishing some of his most important papers.

One of these was The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. This became his most famous work. It explored how culture and religion affect economic systems. This was the only book published during his lifetime from that period. Other important works were published after he died.

In 1904, Weber visited the United States. He attended a big conference in St. Louis. Even though he was feeling better, he didn't go back to regular teaching. He continued as a private scholar, helped by money he inherited in 1907. In 1909, he helped create the German Sociological Association.

His Role in Politics

In 1912, Weber tried to form a new political party. He wanted to bring together social democrats and liberals. But this didn't work because many liberals were afraid of revolutionary ideas.

During World War I

When World War I started, Weber, then 50, volunteered. He helped organize army hospitals in Heidelberg until 1915. His views on the war changed over time. At first, he supported Germany's war efforts. But later, he became a strong critic of Germany's war policies. He spoke out against taking over Belgium and unrestricted submarine warfare. He also supported calls for democratic reforms.

After World War I

In 1918, Weber joined a worker and soldier council in Heidelberg. He was part of the German group at the Paris Peace Conference. He also advised the committee that wrote the Weimar Constitution. He wanted a strong, elected president to balance the power of government workers. He also defended emergency presidential powers, which later became Article 48. This article was later used by Adolf Hitler to gain dictatorial powers.

Weber also ran for a seat in parliament but lost. He was a co-founder of the liberal German Democratic Party. He was against both the German Revolution and the Treaty of Versailles. These strong beliefs might have stopped him from getting a government job. Weber was respected, but he didn't have much political influence.

In January 1919, after losing the election, Weber gave a famous lecture called "Politics as a Vocation." He talked about the challenges and sometimes dishonest nature of politicians. He said that many politicians are "windbags puffed up with hot air about themselves."

His Final Years

Feeling disappointed with politics, Weber went back to teaching. He taught at the University of Vienna and then, after 1919, at the University of Munich. His lectures from this time became important books like General Economic History and Science as a Vocation. In Munich, he led the first German university sociology department.

Many colleagues and students in Munich criticized his views on the German Revolution. Some right-wing students even protested outside his home.

On June 14, 1920, Max Weber got the Spanish flu and died of pneumonia in Munich. He was 56 years old. When he died, he hadn't finished his big book on sociological theory, Economy and Society. His wife, Marianne, helped prepare it for publication in 1921–1922.

How Max Weber Studied Society

Understanding Social Action

Max Weber saw sociology as a science that tries to understand social actions. It then explains why these actions happen and what their effects are. He focused on individuals and their culture.

Unlike some other thinkers, Weber didn't try to create strict rules for sociology. He believed that social actions are tied to specific historical times. To understand them, you need to know what people's reasons were.

The Idea of Verstehen

Weber was very interested in how we can be objective when studying society. He said that social action is different from simple behavior. Social action needs to be understood by how people feel and think about their interactions.

To study social action, you need to use Verstehen (understanding). This means trying to grasp the subjective meaning that people give to their own actions. Even if actions seem clear, their reasons can be very personal. Understanding these reasons is another layer of personal interpretation for the scientist.

Weber noted that because of this personal side, it's harder to create universal laws in social sciences than in natural sciences. He believed that truly objective knowledge in social sciences is limited.

He supported the idea of striving for objective science, even if it's never fully reached. He said, "There is no absolutely 'objective' scientific analysis of culture... All knowledge of cultural reality... is always knowledge from particular points of view."

Weber also believed in "methodological individualism." This means that to understand groups (like nations or governments), you should look at the actions of individual people. He argued that only individuals can truly act in a way that can be understood.

Weber's way of studying society was part of a bigger debate about how social sciences should work. He believed that social actions are deeply connected to history. So, he used comparing historical events to explain why things happened, rather than trying to predict the future.

Max Weber's Key Theories

How Bureaucracy Works

Max Weber's theory of bureaucracy explains how large organizations are structured. He called it the "rational-legal" model. He said bureaucracy is based on clear rules and defined jobs for different offices. These are supported by laws and rules.

Weber pointed out three main parts of bureaucratic administration:

- There's a strict division of labor, meaning everyone has specific tasks.

- There are clear chains of command, showing who reports to whom.

- People are hired based on their skills and qualifications.

He listed nine main features of bureaucracy:

- Everyone has a specialized role.

- People are hired based on their skills, often through tests.

- There are clear rules for hiring, promoting, and moving staff.

- Working in a bureaucracy is a career with a set salary.

- There's a clear hierarchy, with responsibility and accountability.

- Official behavior must follow strict rules and controls.

- Abstract rules are supreme.

- Authority is impersonal; the job is more important than the person doing it.

- The system is politically neutral.

Benefits of Bureaucracy

Weber noted that real bureaucracies are not always perfect. But when these principles are used in a group, they can make an organization more efficient. This is especially true when focusing on skills, specialized jobs, clear power structures, rules, and discipline.

Downsides of Bureaucracy

Sometimes, the rules can be too strict or unclear. In a very rigid bureaucracy, tasks can become routine and boring. Employees might feel like they don't belong or that their creativity isn't valued. This type of organization can also lead to people being exploited.

The Idea of Rationalization

Many scholars say that "rationalization" was the main idea in Weber's work. This is about how society becomes more logical and organized. It also looks at how much freedom individuals have in such a society.

Weber saw rationalization in three ways:

- First, as individuals making decisions based on costs and benefits.

- Second, as organizations becoming more bureaucratic.

- Third, as the world moving away from mystery and magic, becoming more "disenchanted."

He started studying this in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. He argued that Protestantism, especially Calvinism, changed how people viewed work. It made people focus on working hard to gain money, seeing it as a way to show their faith. Over time, the religious reasons faded, but the focus on rational economic effort remained.

Weber continued this idea in his studies of bureaucracy and types of authority. He believed that the world was moving towards rational-legal authority, which is based on rules and logic. He saw this as a key reason why Western societies developed differently from others.

Rationalization means more knowledge, less personal interaction, and more control over social life. Weber had mixed feelings about it. He saw that it brought many good things, like freeing people from old, illogical rules. But he also worried that it would make people feel like "cogs in a machine," trapping them in an "iron cage" of rules and bureaucracy.

The idea of "disenchantment" means the world becomes more explained by science and less by magic. For Weber, rationalization affects all parts of society. It removes "sublime values" from public life and makes art less creative.

He worried about individual freedom in this increasingly rational world. He asked, "How is it at all possible to salvage any remnants of 'individual' freedom... given this all-powerful trend?"

How Religion Affects Society

Weber's work on the sociology of religion started with The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. He then studied The Religion of China, The Religion of India, and Ancient Judaism. He planned to study early Christianity and Islam, but he died before he could.

His main goals were to see how religious ideas affected economic activities and social classes. He also wanted to understand what made Western civilization unique.

Weber believed religion was a core force in society. He wanted to explain why the West and the Orient developed differently. He argued that Calvinism had a big impact on the West's economic system. But he also noted other factors, like scientific thinking and organized government.

He believed that the study of religion in society showed how Western culture moved away from magic, leading to the "disenchantment of the world."

Weber also suggested that religions change over time. Societies generally moved from magic to many gods, then to one God, and finally to ethical monotheism. This happened as societies became more stable and priests became more specialized. As societies grew more complex, the idea of a single, universal God became more popular.

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

This is Weber's most famous book. It suggests that Calvinist ethics and ideas helped develop capitalism. He noticed that after the Reformation, economic power shifted from Catholic countries to Protestant ones like the Netherlands and England. He also saw that successful business leaders were often Protestant.

Weber argued that Roman Catholicism and other religions like Confucianism and Buddhism hindered capitalism. He wrote that the Protestant ethic gave business owners a "fabulously clear conscience." It also gave them "industrious workers."

Historically, Christian faith often meant rejecting worldly things, including making money. But Weber showed that some types of Protestantism, especially Calvinism, supported making money and working hard. They saw these actions as having moral and spiritual meaning.

The idea of a "calling" meant that each person had to work hard to show their salvation. Being rich could even be seen as a sign of being saved. So, people justified making a profit with their religion. Weber called this the "spirit of capitalism." He believed this Protestant religious idea led to the capitalist economic system. This idea is often seen as the opposite of Karl Marx's view that economics determines everything else.

The phrase "work ethic" used today comes from Weber's "Protestant ethic." It was later used to describe hard work in other cultures too.

The Religion of China

In The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism, Weber looked at how Chinese society was different from Western Europe. He wondered why capitalism didn't develop in China. He focused on Chinese cities, government, and religions like Confucianism and Taoism.

Weber believed that Confucianism and Puritanism (a type of Protestantism) were both logical ways of thinking. Both valued self-control and didn't oppose wealth. But their main goals were different. Confucianism aimed for a "cultured status position," while Puritanism aimed to create "tools of God." Working hard for wealth was not seen as proper for a Confucian. Weber argued that these differences in attitudes, shaped by religion, led to capitalism in the West but not in China.

The Religion of India

The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism was Weber's third major work on religion. He studied the structure of Indian society, Hinduism, and Buddhism. He also looked at how religious beliefs affected the everyday ethics of Indian society.

Weber believed that Hinduism, like Confucianism in China, was a barrier to capitalism. The Indian caste system made it hard for people to move up in society. Economic activity was seen as less important than the progress of the soul.

Weber noted that Asian beliefs often focused on a spiritual, otherworldly experience. Society was divided between educated elites and uneducated masses who believed in magic. He said that in Asia, there was no "Messianic prophecy" to give meaning to the daily lives of everyone. This was different from the Near East (where Judaism and Christianity came from). He believed these differences prevented Asian countries from developing like the West. His next book, Ancient Judaism, tried to prove this idea.

Ancient Judaism

In Ancient Judaism, Weber tried to explain what caused the early differences between Eastern and Western religions. He compared the active, worldly focus of Western Christianity with the mystical thinking in India.

Weber said that some parts of Christianity aimed to change the world, not just escape its problems. He believed this key feature of Christianity came from ancient Jewish prophecy.

Weber argued that Judaism not only led to Christianity and Islam but was also crucial for the rise of the modern Western state. He thought Judaism's influence was as important as Greek and Roman cultures.

Weber died before he could finish his planned studies of the Psalms, the Book of Job, Talmudic Jewry, early Christianity, and Islam.

Explaining Good and Bad Fortune

Weber also explored the idea of "theodicy of fortune and misfortune." This theory explains how people from different social classes use different beliefs to understand their social situation.

Theodicy is about how to explain evil or why bad things happen to good people.

- "Theodicies of misfortune" believe that wealth and privilege are signs of evil.

- "Theodicies of fortune" believe that privileges are a blessing and are deserved.

Weber noted that rich people often believe in "good fortune theodicies," thinking their wealth is a blessing from God. Poor people, however, often believe in "theodicies of misfortune," thinking that suffering in this world will be rewarded in the next.

This idea of "work ethic" is linked to the theodicy of fortune. Protestants, with their "work ethic," often had better class outcomes and more education. Those without this work ethic might believe wealth and happiness are for the afterlife. This shows how religious beliefs can influence social class.

For example, wealthier Protestant churches in the U.S. often support the current social order. This is because much of their money comes from their rich members. In contrast, Pentecostal churches, which started among working-class people, might advocate for social change and justice. These different beliefs reinforce social class divisions within religious groups.

Government and Politics

In his essay "Politics as a Vocation" ("Politik als Beruf"), Weber famously defined the "state" as the only group that has a legal "monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force" within a certain area.

He said that politics is about sharing state power among different groups. Political leaders are those who use this power. Weber believed a politician cannot follow a strict "true Christian ethic" of turning the other cheek. A politician needs to balance a passion for their job with the ability to step back and be objective.

Weber identified three "ideal types" of political leadership or authority:

- Charismatic authority: Based on a leader's special personal qualities (like a prophet or a hero).

- Traditional authority: Based on long-standing customs and traditions (like a king or tribal elder).

- Legal authority: Based on laws and rules (like a modern government or bureaucracy).

He believed that all historical relationships between rulers and ruled contained parts of these types. Charismatic authority is often unstable and tends to become more structured over time. The move towards a rational-legal system, with its bureaucratic structure, is often seen as unavoidable in modern society. This links to his broader idea of rationalization.

Weber described many ideal types of public administration in his book Economy and Society (1922). His study of how society became more bureaucratic is a lasting part of his work. He started the study of bureaucracy and made the term popular. Many parts of modern public administration come from his ideas.

Weber listed several things that led to the rise of bureaucracy:

- The growth of areas and populations being managed.

- The increasing complexity of administrative tasks.

- The existence of a money-based economy.

Better communication and transportation also made administration more efficient. People also demanded that the new system treat everyone equally.

Weber's ideal bureaucracy has a clear hierarchy, fixed areas of activity, written rules, expert training for officials, neutral rule enforcement, and career advancement based on skills.

While he saw bureaucracy as the most efficient way to organize, he also saw it as a threat to individual freedoms. He worried that increasing rationalization would trap people in an "iron cage" of rules. To balance this, he believed society needed entrepreneurs and politicians.

Social Classes and Status

Weber also developed a "three-component theory of stratification." This theory says that social class, social status, and political party are different but connected parts of how society is divided. This is different from Karl Marx's simpler idea that social class is only about what people own. In Weber's theory, honor and prestige are also important.

The three parts of Weber's theory are:

- Social class: Based on how people relate to the economy (like being an owner, renter, or employee).

- Status: Based on non-economic qualities like honor, prestige, and religion.

- Party: Being part of political groups.

All three of these affect what Weber called "life chances" (the opportunities people have in life). Scholars keep a clear difference between "status" and "class," even though people often use them interchangeably.

Studying Cities

Weber also studied cities to understand how the Western world developed. He wrote a book called The City, published after he died. He believed that the city, as an independent organization of people with different jobs, was unique to the West. It greatly shaped Western culture.

Weber argued that Judaism, early Christianity, and modern science were only possible in the urban setting that fully developed in the West. He also saw that in medieval European cities, a new type of power emerged. This power came from the economic and military strength of organized city-dwellers, or "citizens." This new power challenged older forms of authority.

Max Weber's Economic Ideas

Weber saw himself mainly as a "political economist." All his teaching jobs were in economics. But today, his work in economics is often overshadowed by his role as a founder of modern sociology.

Economy and Society

Weber's most important work, Economy and Society, is a collection of his essays. He was working on it when he died in 1920. His wife, Marianne, finished organizing and editing it. The book covers his ideas on sociology, social philosophy, politics, social classes, world religions, and more.

Individual Actions in Economics

Weber believed that social scientists should understand groups by looking at the actions of individuals. This idea is called "methodological individualism." He argued that social research cannot just describe things. It must also interpret them. Interpretation means classifying things using abstract "ideal types." This idea helped justify the model of the "rational economic man" (homo economicus) in modern economics.

Economic History

Weber's most famous work in economics was about how capitalism developed. He explored the links between religion and capitalism in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and his other books on the sociology of religion. He argued that bureaucratic political and economic systems in the Middle Ages were key to the rise of modern capitalism.

His other contributions include early work on the economic history of Roman farming (1891) and labor relations in Eastern Germany (1892). He also analyzed the history of business partnerships in the Middle Ages (1889).

Even though sociologists and philosophers read Weber today, his work also influenced economists.

Economic Calculation

Weber believed that "economic calculation" and especially "double-entry bookkeeping" were very important for the development of modern capitalism. He thought that a socialist system would struggle with this. He argued that without prices, central planners would find it hard to decide how to use resources efficiently.

Weber wrote that in a fully socialist economy, it would be unclear how to set "value" indicators for goods. He said, "We cannot speak of a rational 'planned economy' so long as in this decisive respect we have no instrument for elaborating a rational 'plan'."

This argument against socialism was also made by Ludwig von Mises, who was influenced by Weber. Friedrich Hayek later developed these ideas further.

Who Inspired Max Weber?

Kantian Philosophy

Weber's thinking was greatly shaped by German idealism, especially by neo-Kantianism. This philosophy suggests that reality is chaotic, and humans create order by focusing on certain parts of it. Weber's ideas about how to study social sciences are similar to those of the neo-Kantian philosopher Georg Simmel.

Weber was also influenced by Kantian ethics. However, he felt these ethics were outdated in a modern world without strong religious beliefs. Here, the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche also played a role.

Karl Marx's Ideas

Another big influence on Weber was the writings of Karl Marx and socialist ideas. Weber shared some of Marx's concerns about bureaucratic systems. He worried that they could grow too powerful and harm human freedom. However, Weber believed that conflict was always present and didn't think a perfect society was possible.

Karl Löwith compared Marx and Weber. He said both were interested in why Western capitalism developed. But Marx saw capitalism through the idea of "alienation," while Weber used the idea of "rationalization."

Even though Weber was personally not religious, his mother's Calvinism clearly influenced his lifelong interest in studying religions.

Economics and History

As an economist and historian, Weber belonged to the "youngest" German historical school of economics. This group included thinkers like Gustav von Schmoller. While Weber's research interests were similar to this school, his ideas on how to study economics were different. He was closer to Carl Menger and the Austrian School, who were rivals of the historical school.

Occultism

New research suggests that some of Weber's theories were influenced by German occult figures of his time. He visited a group called the Ordo Templi Orientis at Monte Verità before he wrote about "disenchantment." He also met the German poet and occultist Stefan George and developed some ideas about charisma after observing him. However, Weber disagreed with many of George's views and never joined his group.

Max Weber's Lasting Impact

Weber's most important work was in economic sociology, political sociology, and the sociology of religion. Along with Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim, he is seen as one of the founders of modern sociology. Durkheim followed a "positivist" tradition, focusing on measurable facts. But Weber helped develop an "antipositivist" approach, which emphasizes understanding the meaning behind social actions.

Weber saw sociology as the science of human social action. He divided social action into four types: traditional, affectional, value-rational, and instrumental. For Weber, sociology's goal was to understand the meaning of social action and explain its causes and effects.

In his time, Weber was mostly seen as a historian and economist. Many of his famous works were published after he died. Important thinkers like Talcott Parsons and C. Wright Mills later interpreted his writings.

Weber influenced many later social thinkers, including those from the Frankfurt School. His ideas about modernity and rationalization greatly shaped their "critical theory." Different parts of his thinking were highlighted by other economists and philosophers.

Weber's friend, the philosopher Karl Jaspers, called him "the greatest German of our era." Jaspers felt that Weber's early death was "as if the German world had lost its heart."

Some scholars, like Nicholas Gane, see similarities between Weber's work and that of the postmodern philosopher Michel Foucault. Both were concerned with how rationalization affects people's lives. Gane argues that Foucault offered ways for individuals to resist rationalization.

Criticisms of Weber's Ideas

Some academics argue that Weber's explanations are very specific to the historical periods he studied. However, others point out that his ideas are still important today for understanding politics, bureaucracy, and social class.

Many scholars disagree with specific claims in Weber's historical analysis. For example, the economist Joseph Schumpeter argued that capitalism started much earlier, in 14th-century Italy, not with the Industrial Revolution. He noted that cities like Milan, Venice, and Florence developed early forms of capitalism. Also, the Netherlands, which was mostly Calvinist, industrialized later than Catholic Belgium.

His Major Works

Weber wrote in German. Many of his books published after his death (1920) are collections of his unfinished works. Many translations are parts of different German originals, and their names don't always show what they contain. Weber's writings are usually cited from the complete Max Weber-Gesamtausgabe (Collected Works).

See also

In Spanish: Max Weber para niños

In Spanish: Max Weber para niños

- Interpretations of Max Weber's liberalism

- Robert Michels

- Sociology of law

- Speeches of Max Weber

- Werturteilsstreit

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |