Stefan George facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stefan George

|

|

|---|---|

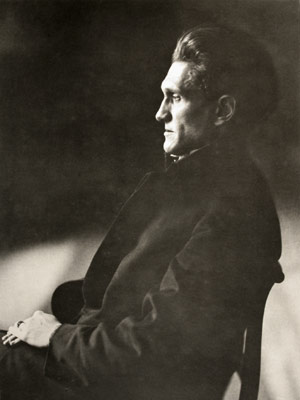

Photograph by Jacob Hilsdorf (1910)

|

|

| Born | Stefan Anton George 12 July 1868 Büdesheim, Grand Duchy of Hesse, German Empire |

| Died | 4 December 1933 (aged 65) Minusio, Ticino, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | German |

| Notable awards | Goethe Prize (1927) |

Stefan Anton George (12 July 1868 – 4 December 1933) was a famous German poet and translator. He translated works by great writers like Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, and Charles Baudelaire. George was also known for leading an important group of writers called the George-Kreis (George-Circle). He started a literary magazine called Blätter für die Kunst ("Journal for the Arts"). From the beginning, George and his followers wanted to create a new style of literature. They were against the realistic writing popular in Germany at the time.

Contents

Stefan George's Life Story

Early Years and Education

Stefan George was born in 1868 in a place called Büdesheim. This town is now part of Bingen am Rhein in Germany. His father, also named Stefan George, ran an inn and sold wine. His mother, Eva, took care of their home. When Stefan was five, his family moved to Bingen am Rhein.

Stefan went to primary school in Bingen. At age thirteen, he was sent to a top secondary school in Darmstadt. There, from 1882 to 1888, he received a strong education. He focused on Greek, Latin, and French languages. Stefan was very good at French. He learned a lot about modern European literature. He also studied ancient Greek and Roman writers. Even though he was described as a loner, Stefan made his first group of friends in Darmstadt. He loved going to libraries and the theater. He even taught himself Norwegian to read plays by Henrik Ibsen.

Becoming a Poet

When he was nineteen, George and some friends started a literary journal. It was called Rosen und Disteln ("Roses and Thistles"). Here, George published his first poems. He used the pen name Edmund Delorme. His school focused on German Romantic poetry. But George taught himself Italian. He wanted to read and translate the Renaissance poets he admired. His first poems were translations and copies of Italian poetry.

After finishing school in 1888, George decided not to go to university or work in business. Instead, he began to travel. He felt that Germany was not a good place for artists at that time.

Hoping to get better at English, George lived in London from May to October 1888. He felt that England had a strong sense of purpose and old traditions. He also discovered English poets like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne. He later translated their works into German.

After a short visit home, George wanted to bring together poets who thought like him. He wanted to publish their works. This idea was common in German literature. Famous poets like Goethe and Schiller also had groups of followers.

In May 1889, George arrived in Paris. He felt very lonely at first. But he soon met French poet Albert Saint-Paul. Through Saint-Paul, George met other writers. He was introduced to famous poets like Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé. Mallarmé invited George to his weekly Symbolist meetings. George had started translating Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal into German. Mallarmé was very happy about this.

Members of Mallarmé's group saw George as a promising poet. George was shy and mostly listened and learned. He filled many pages with poems by French and other European writers. He later translated many of them. The French Symbolists believed in "art for art's sake". This meant that beauty itself was very important. It stood for a higher meaning. George found this idea very appealing.

George admired Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé greatly. He saw Mallarmé as "The Master." Mallarmé became a lifelong role model for George's art and life. George felt that German culture at the time was not good. He thought it was too focused on money and war. He believed German artists were not valued. But his time in Paris made him want to return to Germany. He wanted to give German poetry a new voice.

Starting Blätter für die Kunst

After returning to Germany, George studied languages and literature in Berlin. At first, George doubted if the German language could express what he wanted in his poems. He even invented his own language, Lingua Romana. It mixed Spanish and Latin words with German grammar.

While in Berlin, George teamed up with Carl August Klein. They started an annual literary magazine called Blätter für the Kunst. George felt that German poets were either just providing "pleasant diversion" or criticizing society. He opposed both ideas. Stefan George and Carl Klein wanted Blätter für die Kunst to promote "the new art." This new art would build on and go beyond existing styles. It would also use ideas from the French Symbolists.

George was a very talented and influential supporter of the Symbolist movement in Germany. He didn't just copy others. He put his own mark on Symbolism. He used it to help make German culture and literature stronger.

George was the main leader of the George-Kreis (George-Circle). This group included important young writers like Friedrich Gundolf. The group shared cultural interests. George also knew Fanny zu Reventlow, who sometimes made fun of the group. George's writings were linked to a movement that wanted to change Germany in a traditional way.

In 1914, at the start of World War I, George predicted a sad future for Germany. In 1916, he wrote a poem called "Der Krieg" ("The War"). This poem was against the popular war enthusiasm in Germany.

The war's outcome confirmed his fears. In the 1920s, George disliked German culture. He wanted to create a new, noble German culture. He offered "form" as an ideal. This was a way of thinking and relating to others. He believed it could help Germany during a time of decline.

Views on the National Socialists

Stefan George's ideas were noticed by the National Socialists, who later became the Nazis. They used some of his ideas, like "the thousand year Reich," in their propaganda. However, George came to dislike their ideas about race. He especially disliked the idea of a "Nordic superman."

According to Peter Hoffmann, Stefan George did not think highly of Adolf Hitler. He did not see Hitler as a great leader like Julius Caesar or Napoleon.

In February 1933, the Nazis started removing their political opponents and Jewish people from the Prussian Academy of the Arts. They replaced them with writers who supported the Nazi party. By April 1933, George called the National Socialists "hangmen." He also told his younger followers not to join any Nazi groups.

On May 5, 1933, a Nazi official offered George an honorary position in the Academy. He also offered him a lot of money. The official said they wanted to call George the founder of the Nazi Party's "national revolution."

On May 10, 1933, George replied. He turned down both the money and the position. He said he had managed German literature for fifty years without needing an academy. However, he did not deny that his ideas might have influenced the new national movement.

Some Nazis were angry about George's refusal. They doubted his support for their revolution. Some even falsely called him a Jew.

In July, George returned to Bingen am Rhein to renew his passport. But he left for Berlin-Dahlem just four days before his 65th birthday. Some historians believe he did this to avoid official honors from the new government. The government did not try to honor him again, except for a telegram from Joseph Goebbels.

Death in Switzerland

On July 25, 1933, George traveled to Wasserburg in Germany. He stayed there for four weeks. Younger members of the George-Circle, including Claus von Stauffenberg, visited him.

On August 24, 1933, George took a ferry to Heiden, Switzerland. He had chosen to go to Switzerland to escape the humid air. He also joked that he could breathe more easily in the middle of the lake, hinting at his dislike for the situation in Germany.

Stefan George died in Minusio, Switzerland, on December 4, 1933. Some of his followers wanted to bring his body back to Germany. But his heir, Robert Boehringer, said George wanted to be buried where he died.

The George-Circle decided to bury him in Minusio. Claus von Stauffenberg arranged the wake. The group kept watch at the cemetery chapel. The German Consulate asked about the funeral details. The George-Circle said the funeral would be on December 6 at 3 PM. They also said they did not want mourners from outside the Circle. So, they secretly changed the funeral time to 8:15 AM on December 6.

Twenty-five members of the George-Circle attended the funeral. This included Jewish members like Ernst Morwitz and Karl Wolfskehl. The German Foreign Office sent a wreath with a swastika on it. Some members of the Circle kept removing the swastika ribbon. Others kept replacing it with new ones. As mourners left the train station, some younger members gave the Nazi salute.

Stefan George's Legacy

When Stefan George died in 1933, there were different opinions about him. People inside Germany claimed he was a prophet for the new Nazi government. But people outside Germany often thought his silence showed his dislike for the new regime.

Literary Achievements

From the start, George and his followers wanted to change German literature. They were against the realistic style popular in the late German Empire.

George was also important in connecting different literary periods. He linked 19th-century German Romanticism to 20th-century Expressionist and Modernist poetry. George was a strong critic of his own time, but he was also a product of it.

George's poetry has a noble style. His poems are formal and lyrical. They often use old or special words. He was influenced by ancient Greek forms. His poetry helped shape modern literary German. He also tried different poetic rhythms, punctuation, and ways of arranging words.

George believed that poetry should create an alternative to reality. He strongly supported "art for art's sake." This means art should be valued for its beauty, not for any other purpose. His ideas about poetry came from the French Symbolist poets. He saw himself as a student and follower of Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine.

Algabal is one of George's most famous poetry collections. Its title refers to the Roman emperor Elagabalus. George was also an important translator. He translated works by Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, and Charles Baudelaire into German.

George received the Goethe Prize in 1927.

Das neue Reich (The New Realm)

George's last complete book of poems, Das neue Reich ("The New Realm"), was published in 1928. It was banned in Germany after World War II. This was because its title sounded like it supported Nazism. But George had dedicated this work to Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg. Berthold and his brother Claus von Stauffenberg played a key role in the 20 July plot. This was a plan to kill Adolf Hitler and overthrow the Nazi Party. Both brothers believed they were following George's teachings by trying to end Nazism. The book describes a new society led by a spiritual group. George did not want his work used for political purposes, including Nazism.

Influence on Others

George and his followers saw him as the leader of a special group in Germany. This group was made up of his intellectual and artistic students. They were loyal to "The Master" and shared his vision. Albert Speer, a Nazi official, claimed to have met George. Speer said George had a magnetic presence.

George's poetry focused on self-sacrifice, heroism, and power. This made the National Socialists approve of him. Many Nazis claimed George influenced them. But George stayed away from such connections. Soon after the Nazis took power, George left Germany for Switzerland. He died there the same year.

Some members of the 20 July plot against Hitler were George's followers. This included the Stauffenberg brothers. George's circle also included Jewish authors like Gundolf and Karl Wolfskehl. George liked his Jewish students.

George greatly influenced Ernst Kantorowicz. Kantorowicz wrote a famous biography of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in 1927. The book described Frederick II as a strong leader who could shape his empire. This idea matched the goals of the George Circle. George even helped correct the manuscript and made sure it was published.

One of George's well-known collaborators was Hugo von Hofmannsthal. He was a leading writer in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Hofmannsthal later wrote that George influenced him more than anyone else. Those closest to "The Master" included several members of the plot to kill Hitler. Claus von Stauffenberg often quoted George's poem Der Widerchrist (The Anti-Christ) to his fellow plotters.

George's Poetry in Music

Stefan George's poetry had a big impact on 20th-century classical music. This was especially true for the Second Viennese School.

- The composer Arnold Schönberg used George's poetry in his String Quartet No. 2 (1908) and The Book of the Hanging Gardens (1909).

- Schönberg's student Anton Webern also set George's poetry to music in his early choral work and other songs.

Movies Related to Stefan George

- Rainer Werner Fassbinder's 1976 comedy film Satan's Brew makes fun of Stefan George and the George-Circle.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Stefan George para niños

In Spanish: Stefan George para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |