Jacques Ellul facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacques Ellul

|

|

|---|---|

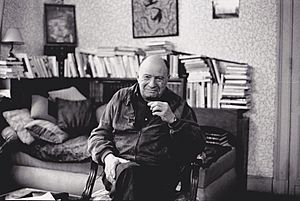

Ellul in 1990

|

|

| Born | January 6, 1912 |

| Died | May 19, 1994 (aged 82) |

| Education | University of Paris |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Christian anarchism Continental philosophy< Non-conformists of the 1930s |

|

Notable ideas

|

Technological society |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

Greg Boyd, Cornelius Castoriadis, Vernard Eller, Ivan Illich, Ted Kaczynski, Randal Marlin, Thomas Merton, Robert K. Merton, William Stringfellow, Paul Virilio, Langdon Winner, Neil Postman, John Zerzan, Willem H. Vanderburg, Guy Debord, José Bové, Egbert Schuurman, Bernard Charbonneau, Serge Latouche, Marva Dawn, Bruno Latour, Stanley Hauerwas, Dominique Bourg, Jean-Claude Guillebaud, Noel Mamère, Alexandre Christoyannopoulos, Shane Claiborne, Timothy Keller, Rustum Roy, Carl Mitcham, Jim Wallis, Ursula Franklin, Brian Brock, George Grant, Christopher Lasch, Andrew Feenberg, James M. Houston, Radovan Richta, George Dyson, Yuk Hui, Albert Borgmann, Jean-Luc Nancy, Olivier Abel, Michel Leplay, Jacques Maury, André Vitalis, Alain Gras |

|

Jacques Ellul (January 6, 1912 – May 19, 1994) was a French thinker, writer, and professor. He was known for his ideas on how technology affects society. He also wrote a lot about propaganda and the connection between religion and politics.

Ellul taught history and sociology at the University of Bordeaux for many years. He wrote over 60 books and 600 articles. A main idea in his work was the danger that modern technology poses to human freedom and faith. He didn't want to get rid of technology. Instead, he wanted people to see it as a tool, not something that controls our lives. His most famous books are The Technological Society and Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes.

Many people see Ellul as a philosopher. But he was trained as a sociologist. He looked at technology and human actions from a special viewpoint. He often wrote about how technology could become a tyrant over people. He also explored how technology became like a religion in modern society. In 2000, a group of his former students started the International Jacques Ellul Society. This group continues to study his ideas and discuss how they apply today.

Contents

Early Life and Key Influences

Jacques Ellul was born in Bordeaux, France, on January 6, 1912. His mother, Marthe Mendes, was French-Portuguese and Protestant. His father, Joseph Ellul, was from Malta and became a deist. When Jacques was a teenager, he wanted to be a naval officer. However, his father encouraged him to study law. He married Yvette Lensvelt in 1937.

Ellul studied at the universities of Bordeaux and Paris. During World War II, he was an important leader in the French Resistance. He helped save Jewish people from danger. For this, he was later honored with the title Righteous Among the Nations in 2001. He was also a member of the Reformed Church of France and held a high position there.

Ellul was best friends with Bernard Charbonneau, another writer from France. They met in 1929–1930 and greatly influenced each other's ideas.

By the early 1930s, three main thinkers inspired Ellul: Karl Marx, Søren Kierkegaard, and Karl Barth. Ellul studied Marx's ideas deeply. He also read all the works of Marx and Kierkegaard. He considered Karl Barth, a leader against the German state church in World War II, the greatest theologian of his time. Ellul also said his father was a big role model for him.

In 1932, Ellul became a Christian. He described it as a "very brutal and very sudden conversion." He felt a powerful presence while translating Faust one summer. This experience led him to believe he was in the presence of God. This started a conversion process that continued for several years. Even though he was a Protestant, he often criticized churches. He felt they didn't focus enough on Jesus' teachings or the Bible.

Ellul also supported the worldwide ecumenical movement, which tries to unite different Christian churches. However, he later became critical of it. He felt it too easily supported political systems. Ellul also liked the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Proudhon believed that creating new groups from the ground up was the best way to build an anarchist society. Ellul felt his own views were similar to anarcho-syndicalism. He wanted change to happen slowly, by transforming media and economic systems. He imagined an anarchist society based on cooperation. He even believed Jesus was an anarchist, saying "anarchism is the fullest and most serious form of socialism."

Ellul is often credited with saying, "Think globally, act locally." He chose to spend most of his career in Bordeaux, the city where he was born. Jacques Ellul passed away on May 19, 1994, in Pessac, three years after his wife, Yvette.

Ellul's Views on Theology

While Ellul was mostly known for his sociology and ideas on technology, he saw his theological work as very important. He started publishing books on theology early in his career, like The Presence of the Kingdom (1948).

Ellul was a French Protestant, influenced by thinkers like John Calvin. However, he often disagreed with traditional Protestant ideas. He didn't like how some thinkers mixed philosophy or romantic ideas with their beliefs about God. Instead, he mainly used the works of Karl Barth and Søren Kierkegaard. These thinkers criticized how European churches worked with the state. Ellul believed that God is completely free to do what God wants. He thought that trying to limit God's freedom with human ideas of right and wrong was a mistake.

Ellul believed that all people, from the beginning of time, are saved by God through Jesus Christ. He thought everyone receives God's divine grace, no matter what they have done. This idea is called Christian Universalism. He believed this not because he thought humans were so good, but because he had a very high view of God's power and freedom.

Understanding Technique and Technology

Ellul's most important work is often considered The Technological Society (1964). In this book, he explained his idea of "technique." He defined technique as "all the methods that are thought out carefully to be as efficient as possible in every human activity." He stressed that technique is not just machines or technology. It's also about the most efficient way to do things.

Ellul pointed out seven features of modern technology that make efficiency so important:

- Rationality: Technology makes things logical and organized, like dividing work into small steps.

- Artificiality: It creates systems that change or control the natural world.

- Automatism of technical choice: We often choose the most efficient technical solution without thinking about other options.

- Self-augmentation: Technology grows and improves on its own, almost without human effort.

- Monism: All techniques tend to become one big, connected system.

- Universalism: Technique applies everywhere, no matter the culture or place.

- Autonomy: Technology seems to develop independently of human control.

Ellul worried that instead of humans controlling technology, humans have to adapt to it. He believed that technology demands total change from us. For example, he noted how the humanities (like studying old languages or history) seem less important in a technological society. People might question why they should learn things that don't directly help their finances or technical skills.

Ellul thought this focus on technology was a problem in modern education. Schools might put too much stress on information and computers. They prepare young people to work with computers, but only teach them the computer's logic and language. This way of thinking, he argued, is taking over all areas of thought and conscience.

Ellul believed that what was once considered "sacred" (like nature or the church) has been replaced by technology. People now treat the technological society itself as sacred.

He argued that we can't separate technology from how it's used. This is because technologies have specific effects on society and people, no matter what we intend. So, what's the solution? Ellul suggested we should simply see technology as useful objects. We should recognize it for what it is: just one thing among many. If we do this, we can "destroy the basis for the power technique has over humanity."

Views on Justice

Ellul believed that true freedom and social justice were difficult to have at the same time. He thought a Christian could join a movement for justice. But they must understand that fighting for justice also means fighting against some forms of freedom. Social justice might protect people from being controlled, but it also makes life subject to certain rules.

Ellul believed that when Christians act, they should do so in a way that is uniquely Christian. He said, "Christians must never identify themselves with this or that political or economic movement." Instead, they should bring something special to social movements. He felt that if Christians act just like everyone else, there's nothing special or Christian about it.

In his book Violence, Ellul stated that only God can bring true justice. He believed God would establish a perfect kingdom at the end of time. He knew some people used this idea to do nothing. But he also pointed out that others claimed, "we ourselves must undertake to establish social justice." Ellul argued that without believing in God, love and the search for justice become limited. He questioned how we define justice. He felt that some people who wanted justice only cared about certain groups of poor people.

Media, Propaganda, and Information

Ellul explored these topics in detail in his important book, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes. He saw the power of the media as another way technology controls human lives. He believed that media is almost always used by special groups, whether they are businesses or governments.

In Propaganda, Ellul also said that "too much information does not make the reader or listener smarter; it drowns them." People can't remember or understand all the facts. They just get a general idea. The more facts given, the simpler the overall picture becomes. He argued that people get "caught in a web of facts they have been given." They can't make their own choices or judgments on other topics.

Ellul believed that modern information systems can create a kind of "hypnosis" in people. Individuals can't escape the ideas that have been set out for them by the information. He said that propaganda creates an "inner control over the individual by a social force." This means it takes away a person's ability to think for themselves.

Ellul agreed with Jules Monnerot, who said, "Any strong personal feeling leads to stopping all critical thinking about the thing that causes that feeling."

Ellul visited Germany twice in the 1930s. On his second visit, he attended a Nazi meeting. This experience helped him understand propaganda and its power to unite a group.

On Humanism

Ellul believed that modern society often praises and worships human achievements. This includes things like the nation, the state, money, technology, art, and morality. He argued that while we glorify these human creations, they can also end up controlling and limiting humankind.

See also

In Spanish: Jacques Ellul para niños

In Spanish: Jacques Ellul para niños

- Christian anarchism

- Christian libertarianism

- Indoctrination

- John Zerzan

- Koyaanisqatsi

- Langdon Winner

- Noam Chomsky

- Non-conformists of the 1930s

- Philosophy of technology

- Randal Marlin

- Slavoj Žižek

- Ted Kaczynski and the Unabomber Manifesto, influenced by the philosophy of Jacques Ellul

- Universal reconciliation

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |