Thorstein Veblen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thorstein Veblen

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Thorstein Bunde Veblen

July 30, 1857 Cato, Wisconsin, U.S.

|

| Died | August 3, 1929 (aged 72) Menlo Park, California, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Institutions | |

| Field | Economics, socioeconomics |

| School or tradition |

Institutional economics |

| Alma mater |

|

| Influences | Herbert Spencer, Thomas Paine, William Graham Sumner, Lester F. Ward, William James, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, Edward Bellamy, John Dewey, Gustav von Schmoller, John Bates Clark, Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier |

| Contributions | Conspicuous consumption, conspicuous leisure, trained incapacity, Veblenian dichotomy |

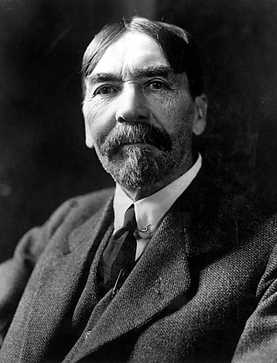

Thorstein Bunde Veblen (born July 30, 1857 – died August 3, 1929) was an American economist and sociologist. He was known for being a strong critic of capitalism, an economic system where private businesses own most things.

In his most famous book, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Veblen created the ideas of conspicuous consumption and conspicuous leisure. These terms describe how people show off their wealth. Many experts see Veblen as the founder of a way of thinking called institutional economics. Today, economists still use Veblen's ideas about the difference between "institutions" (like rules and customs) and "technology." This idea is called the Veblenian dichotomy.

Veblen was an important thinker during the Progressive Era in the US. He criticized the idea of making things just for profit. His focus on conspicuous consumption greatly influenced other economists. They used his ideas to critique fascism, capitalism, and how technology shapes society.

Contents

About Thorstein Veblen

His Early Life and Family

Thorstein Veblen was born on July 30, 1857, in Cato, Wisconsin. His parents, Thomas Veblen and Kari Bunde, were immigrants from Norway. Thorstein was the sixth of twelve children in his family.

His parents came to America in 1847 with little money and did not speak English. But his father was skilled in carpentry, and his mother was very determined. They managed to start a family farm in Rice County, Minnesota, where they moved in 1864. This farm, near Nerstrand, later became a famous historical place in 1981.

Veblen started school when he was five. Even though Norwegian was his first language, he learned English from his neighbors and at school. His parents also learned English well. The family farm became successful, which allowed Veblen's parents to send all their children to school. Veblen and all his brothers and sisters went to Carleton College nearby. His sister, Emily, was said to be the first daughter of Norwegian immigrants to finish college in America. His oldest brother, Andrew, became a physics professor. Andrew's son, Oswald Veblen, became a leading mathematician.

Some people believe that Veblen's Norwegian background and his life in a "Norwegian society within America" helped him see American society differently. He was not fully part of his parents' old culture, nor did he fully fit into American culture. This unique view helped shape his writings.

His Education Journey

At age 17, in 1874, Veblen went to Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. Even then, he showed a mix of sharp criticism and humor that would appear in his later books. He studied economics and philosophy with John Bates Clark, who later became a leader in neoclassical economics. Clark helped Veblen start studying economics formally. Veblen began to understand the limits of some economic ideas, which influenced his own theories. He also became interested in social sciences, studying philosophy, natural history, and classical languages.

After graduating from Carleton in 1880, Veblen went to Johns Hopkins University to study philosophy. When he couldn't get a scholarship there, he moved to Yale University. At Yale, he found financial help for his studies. He earned his PhD in 1884, focusing on philosophy and social studies. He studied with famous professors like Noah Porter and William Graham Sumner.

His Marriages

Veblen met his first wife, Ellen Rolfe, at Carleton College. She was the niece of the college president. They married in 1888. They separated many times and divorced in 1911. After Ellen passed away in 1926, it was found that she had a condition that made it impossible for her to have children. A book by Veblen's stepdaughter suggested this explained why Ellen was not interested in a typical marriage. She said Veblen treated Ellen "more like a sister."

In 1914, Veblen married Ann Bradley Bevans, who used to be his student. He became a stepfather to her two daughters, Becky and Ann. They seemed to have a happy marriage. Ann was described as a supporter of women's rights, socialism, and workers' rights. They hoped to have a child, but Ann had a miscarriage. Veblen never had any children of his own.

His Later Years

After his wife Ann died in 1920, Veblen took care of his stepdaughters. Becky moved with him to California and looked after him until he died in August 1929. Veblen earned a good salary from The New School. He lived simply and invested his money in California raisin farms and the stock market. Sadly, he lost his investments. He then lived in a house in Menlo Park, California, which had belonged to his first wife. He lived on money from his book sales and a yearly sum from a former student until he died in 1929.

Veblen's Work and Ideas

Starting His Academic Career

After graduating from Yale in 1884, Veblen didn't have a job for seven years. Even with good recommendations, he couldn't find a university position. Some people think it was because he was Norwegian, or because he wasn't trained in Christianity like most professors then. Veblen also openly said he was an agnostic, which was unusual at the time. He went back to his family farm, where he spent years reading a lot. These early struggles might have inspired his book The Higher Learning in America (1918). In it, he said that universities sometimes cared more about making money than about true learning.

In 1891, Veblen went back to graduate school at Cornell University to study economics. With help from a professor, he became a fellow at the University of Chicago in 1892. He worked on the Journal of Political Economy and used it to publish his own writings. He also wrote for other journals. Even though he wasn't a central figure at the University of Chicago, he taught several classes there.

In 1899, Veblen published his first and most famous book, The Theory of the Leisure Class. This book didn't immediately improve his job situation at the University of Chicago. He asked for a raise after the book came out, but it was denied.

Veblen's students at Chicago found his teaching "dreadful." Students at Stanford also found him "boring." In 1909, he had to leave his job at Stanford, which made it hard for him to find another teaching position.

In 1911, Veblen took a job at the University of Missouri. He didn't like it there, partly because the job was lower in rank and paid less. He also disliked the town of Columbia, Missouri. Despite this, he published another well-known book in 1914, The Instincts of Worksmanship and the State of the Industrial Arts. After World War I began, he published Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution (1915). He believed war harmed economic production. He compared Germany's strict politics with Britain's democratic ways, noting that industrial growth in Germany hadn't led to more open politics.

By 1917, Veblen moved to Washington, D.C. He worked with a group helping President Woodrow Wilson plan for peace after World War I. This led to his book An Inquiry into the Nature of Peace and the Terms of Its Perpetuation (1917). After this, he worked for the United States Food Administration. Later, he moved to New York City to be an editor for a magazine called The Dial. He lost this job when the magazine changed its focus.

Veblen then connected with other thinkers like Charles A. Beard and John Dewey. These professors and intellectuals founded The New School for Social Research in 1919. Veblen continued to write and help develop The New School until 1926. During this time, he wrote The Engineers and the Price System. In this book, Veblen suggested that engineers, not workers, might lead to changes in capitalism.

Institutional Economics

Thorstein Veblen helped create institutional economics. He criticized older economic theories that saw the economy as separate and unchanging. Veblen believed that the economy was deeply connected to social institutions, like customs, habits, and laws. He thought that economics should not be separated from other social sciences. Instead, he saw how the economy, society, and culture all influenced each other.

Institutional economics looks at how economic institutions are part of a larger cultural development. While it didn't become the main way of thinking in economics, it allowed economists to study economic problems by including social and cultural factors. It also helped them see the economy as something that is always changing.

Conspicuous Consumption

In his most famous book, The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen criticized the leisure class. This group of people had a lot of free time and money. He said they wasted money on things just to show off. Veblen called this conspicuous consumption. He defined it as spending more money on goods than they are truly worth.

This idea came about during the Second Industrial Revolution. At that time, a new group of rich people appeared because they had gained a lot of money. Veblen explained that these wealthy people, often in business, used conspicuous consumption to impress others. They wanted to show their social power and high status, whether it was real or just how they wanted to be seen. So, social status became about what you bought and displayed, not just how much money you earned. Veblen argued that people in other social classes then tried to copy the leisure class. This behavior, he said, led to a society that wasted time and money. Unlike other studies of the time, Veblen's book focused on how people consumed, not just how things were produced.

Conspicuous Leisure

Conspicuous leisure means using time in a non-productive way just to show off your social status. Veblen saw this as a key sign of the leisure class. If you engaged in conspicuous leisure, you were openly showing your wealth and status. Doing productive work, on the other hand, suggested you weren't rich and was seen as a sign of weakness. As the leisure class spent more time avoiding productive work, this avoidance itself became a mark of honor. Actually working hard became a sign of being lower class.

Conspicuous leisure worked well to show social status in the countryside. But in cities, it became harder to use leisure alone to display wealth. City life needed more obvious ways to show status, wealth, and power. This is where conspicuous consumption became more important.

The Leisure Class

In The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen looked at how conspicuous consumption and the leisure class fit into society's buying habits and social levels. He traced these behaviors back to early tribal times, when people first started dividing up work. In those times, high-status people in a community did things like hunting and war. These jobs were less physically demanding and less about making useful goods. Lower-status people did more productive and harder work, like farming and cooking.

Veblen explained that high-status people could afford to live a leisurely life. They were part of the economy in a symbolic way, not by doing practical work. These individuals could enjoy conspicuous leisure for long periods, simply doing things that showed their higher social status. They didn't need to engage in conspicuous consumption as much. The leisure class kept their social status and control by, for example, taking part in war. Even though war wasn't always happening, it made the lower classes depend on them.

In modern industrial times, Veblen described the leisure class as those who didn't have to do factory work. Instead, he said, they did intellectual or artistic things to show they didn't need to do manual labor to earn money. Basically, not having to do hard physical work wasn't what gave you high social status. Instead, having high social status meant you didn't have to do such duties.

How He Saw the Rich

Veblen added to Adam Smith's ideas about the rich. He said that "the leisure class used charitable activities as one of the ultimate benchmarks of the highest standard of living." Veblen suggested that to get rich people to share their money, they needed to get something in return, like pride or honor. This idea is similar to how Behavioral economics shows that rewards and incentives are important in how people make choices. When rich people feel proud and honored for giving to charity, everyone benefits.

In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Veblen called communities without a leisure class "non-predatory communities." He also stated that "the accumulation of wealth at the upper end of the pecuniary scale implies privation at the lower end of the scale." This means that when some people get very rich, others might have less. Veblen believed that inequality was natural.

The Theory of Business Enterprise

Veblen saw a main problem as the conflict between "business" and "industry."

He defined business as the owners and leaders whose main goal was to make profits for their companies. But to keep profits high, they often tried to limit how much was produced. By blocking the industrial system in this way, "business" hurt society as a whole. For example, it could lead to higher unemployment. Veblen believed that business leaders caused many problems in society. He felt that society should be led by people like engineers. Engineers understood the industrial system and how it worked, and they also cared about the well-being of everyone.

Trained Incapacity

In sociology, trained incapacity means that a person's skills or past experiences can become weaknesses or blind spots. It means that what people learned in the past can make them make wrong decisions when situations change.

Veblen first used this phrase in 1914, in his book The Instinct of Workmanship and the Industrial Arts.

Veblen's Economic and Political Views

Veblen and other American thinkers who followed institutionalism were influenced by the German Historical School. This school focused on historical facts, using evidence, and studying things in a broad, evolutionary way. Veblen admired some of their ideas.

Veblen developed an evolutionary economics in the 20th century. It was based on Darwinian ideas and new thoughts from anthropology, sociology, and psychology. Unlike the neoclassical economics that came out at the same time, Veblen said that economic behavior was shaped by society. He saw economic organization as a process that was always changing. Veblen did not like theories that focused only on individual actions or inner personal reasons. He thought such theories were "unscientific."

He believed this evolution was driven by human instincts like copying others, hunting for resources, craftsmanship, caring for family, and simple curiosity. Veblen wanted economists to understand how social and cultural changes affected economic changes. In The Theory of the Leisure Class, the instincts of copying and hunting play a big role. People, rich and poor, try to impress others and gain advantages through what Veblen called "conspicuous consumption" and "conspicuous leisure." In this book, Veblen argued that what you buy is used to gain and show status. "Conspicuous consumption" often led to "conspicuous waste," which Veblen disliked.

Political Ideas

Politically, Veblen supported the idea of the government owning things. Experts have different opinions on how much Veblen's ideas fit with Marxism, socialism, or anarchism.

Veblenian Dichotomy

The Veblenian dichotomy is an idea Veblen first mentioned in The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). He fully developed it in The Theory of Business Enterprise (1904). For Veblen, institutions (like rules and customs) decide how technologies are used. Some institutions are more "ceremonial" than others.

Veblen defined "ceremonial" as being about the past. It supports old traditions and ways of doing things. The "instrumental" side, however, focuses on technology and its purpose. It judges value by how well something can control future results.

This idea suggests that every society uses tools and skills to live. But every society also seems to have a "ceremonial" structure of status that goes against the needs of the "instrumental" (technological) parts of group life. The Veblen Dichotomy is still important today. It can help us understand things like digital transformation.

Veblen's Lasting Impact

Veblen is seen as one of the founders of the American school of institutional economics, along with John R. Commons and Wesley Clair Mitchell. Economists who follow this school belong to groups like the Association for Institutional Economics. The Association for Evolutionary Economics gives an annual Veblen-Commons award for work in this field.

Veblen's work is still important today, not just for the phrase "conspicuous consumption". His way of studying economic systems, which looks at how they change over time, is becoming popular again. His idea of ongoing conflict between the old ways and new ways can help us understand the global economy. For example, some writers have compared Veblen's time, the Gilded Age, to our current "New Gilded Age." They see a new global leisure class and unique luxury spending patterns.

Veblen's work has also been used by feminist economists. Veblen believed that women's behavior showed the social norms of their time and place. He thought women in the industrial age were still affected by their "barbarian status." In hindsight, this has made Veblen seem like an early supporter of modern feminism.

Veblen's work has also appeared in American books. He is a character in The Big Money by John Dos Passos. He is also mentioned in Carson McCullers' The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter and Sinclair Lewis's Main Street. One of Veblen's students was George W. Stocking, Sr., who helped start the field of industrial organization economics. Another student was Canadian writer Stephen Leacock, who later led the Economics and Political Science Department at McGill University. You can see Veblen's influence in Leacock's 1914 satire, Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich.

Even today, Veblen is not very well known in Norway. However, President Clinton once honored Veblen as a great American thinker when speaking to King Harald V of Norway.

Veblen goods are named after him. These are luxury items that people buy more of when their price goes up, because they want to show off their wealth. This idea comes from Veblen's work in The Theory of the Leisure Class.

See also

In Spanish: Thorstein Veblen para niños

In Spanish: Thorstein Veblen para niños

- Affluenza

- Anti-consumerism

- Mottainai

- Simple living

- Veblen good

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |