Charles A. Beard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

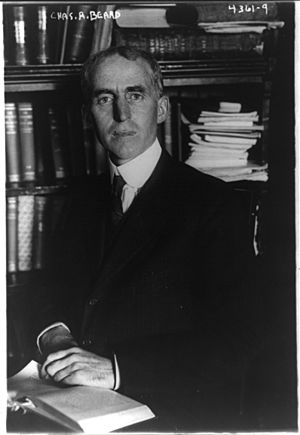

Charles Austin Beard

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait, 1917

|

|

| Born |

Charles Austin Beard

November 27, 1874 Knightstown, Indiana, U.S.

|

| Died | September 1, 1948 (aged 73) New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | DePauw University (B.A., History, 1898) Columbia University (Ph.D., 1904) |

| Occupation | |

| Years active | 1902 – 1948 |

|

Notable work

|

An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States The Rise of American Civilization |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Ritter Beard

(m. 1900) |

Charles Austin Beard (born November 27, 1874 – died September 1, 1948) was an American historian and professor. He wrote many books and articles in the first half of the 20th century.

Beard taught history at Columbia University. He became very famous for his ideas about history and political science. He had a new way of looking at the Founding Fathers of the United States. He thought they were more interested in economics (money and business) than in big ideas or philosophy.

His most famous book was An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States, published in 1913. This book caused a lot of debate. People still discuss it today. Even though some people disagreed with his methods, his book changed how many historians looked at early American history.

Beard was a leader of the "progressive" way of thinking about history. This means he believed that history was shaped by struggles between different groups, often based on their economic interests. Later, during the Cold War, his ideas about class conflict (different social classes fighting for power) became less popular. However, some historians still praised him for trying to find a "usable past" – meaning history that could help people understand their present.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Indiana

Charles Austin Beard was born on November 27, 1874. He grew up in Knightstown, Indiana. His father was a farmer, a builder, and also worked with money and land.

When Charles was young, he worked on his family's farm. He went to a local Quaker school called Spiceland Academy. He later graduated from Knightstown High School in 1891. For a few years, he and his brother ran a local newspaper. They supported the Republican Party and were against alcohol, a cause Charles spoke about later.

College and Graduate Studies

Beard went to DePauw University, a college nearby, and finished in 1898. He was the editor of the college newspaper and enjoyed debate.

In 1899, Beard traveled to England for more studies at Oxford University. There, he helped start Ruskin Hall. This was a special school designed to be affordable for working people. Students could pay less if they worked for the school. Beard taught at Ruskin Hall and gave talks to workers in different towns. He wanted to encourage them to join Ruskin Hall or take its online courses.

He came back to the United States in 1902. He continued his history studies at Columbia University and earned his doctorate degree in 1904. Right after, he became a teacher there. In 1900, Charles married his classmate Mary Ritter Beard. Mary was also a historian. She was interested in feminism (women's rights) and the labor union movement. Charles and Mary worked together on many textbooks.

Career Highlights

Teaching at Columbia University

After getting his doctorate, Charles Beard became a lecturer at Columbia University. He made it easier for his students to find reading materials. He put together many essays and writings into one book called An Introduction to the English Historians (1906). This was a new idea at the time.

Beard was a very busy writer. He wrote many scholarly books, textbooks, and articles for political magazines. His career grew quickly. He moved from the history department to the public law department. Then he got a new position in politics and government. He also taught American history at Barnard College. Besides teaching, he coached the debate team and wrote about public issues, especially how to improve cities.

His most debated book during his time at Columbia was An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913). In this book, he looked at how the money interests of the people who wrote the Constitution might have affected their decisions. He pointed out the differences between farmers and business owners. Many academics and politicians criticized the book. However, scholars respected it until the 1950s.

Leaving Columbia and Independent Work

Beard strongly supported the United States joining the First World War. He left Columbia University on October 8, 1917. He felt that the university was controlled by a small group of leaders who were against new ideas. He believed he couldn't support the war effort effectively while working for them. After other teachers also left Columbia over issues of academic freedom, his friend James Harvey Robinson also resigned. Robinson helped start the New School for Social Research in 1919.

After leaving Columbia, Beard never took another full-time teaching job. He was financially secure because his textbooks and other popular books, like The Rise of American Civilization (1927), earned him a lot of money. He and his wife also ran a dairy farm in Connecticut. Many academics visited them there. The Beards helped create the New School for Social Research in Manhattan. This school was special because its teachers had more control over how it was run.

Beard also traveled to Japan. He wrote a book with ideas for rebuilding Tokyo after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.

Beard had two main careers: as a historian and a political scientist. He was active in the American Political Science Association and became its president in 1926. He was also a member of the American Historical Association and was its president in 1933. In political science, he was known for his textbooks and his studies of the Constitution. He also helped create groups that studied city government and public administration.

World War II and Later Views

Beard did not agree with President Franklin Roosevelt's foreign policy. Because of his Quaker background, he became a strong supporter of non-interventionism. This meant he wanted the United States to stay out of World War II. He believed the U.S. had no important interests in Europe. He also worried that a foreign war could lead to a dictatorship at home.

He continued to hold these views even after World War II ended. In his last two books, American Foreign Policy in the Making: 1932–1940 (1946) and President Roosevelt and the Coming of War (1948), Beard claimed that Roosevelt lied to the American people to get them into the war. Some historians and political scientists disagree with this claim. Because of his views, he was sometimes called an isolationist.

However, some of his ideas from President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War influenced later historians in the 1960s. His views on not getting involved in foreign wars have also become popular again with some scholars since 2001. Charles Beard died in New Haven, Connecticut, on September 1, 1948. He was buried in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. His wife, Mary, was buried there ten years later.

Charles Beard's Legacy

Progressive History

By the 1950s, Beard's idea that history was mainly shaped by economics became less popular. Only a few historians still believed that class conflict was the main force in American history.

However, as a leader of the "progressive historians", Beard brought up important ideas. He suggested that the Constitution was adopted because of economic self-interest and conflicts. He also thought the Civil War was caused by big changes in the economy. He highlighted a long-standing conflict between business owners in the Northeast, farmers in the Midwest, and plantation owners in the South. He saw this conflict as the main cause of the Civil War.

His study of the financial interests of the people who wrote the U.S. Constitution (in An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution) seemed very new in 1913. He suggested that the Constitution was a result of the economic goals of the Founding Fathers who owned land. He believed that people's ideas came from their economic interests.

Views on the Constitution

Another historian, Carl L. Becker, suggested that the American Revolution had two parts. One was fighting Britain for independence. The other was deciding who would rule at home. Beard expanded on this idea, focusing on class conflict. He wrote about it in An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913) and An Economic Interpretation of Jeffersonian Democracy (1915).

Beard believed the Constitution was created by wealthy bondholders to stop the strong democratic ideas that came from the Revolution. He thought it was a way for rich people to protect their money from farmers and people who owed money. He argued that the Constitution was designed to reverse the radical changes that the Revolution brought for common people, especially farmers and debtors.

By 1950, many scholars had accepted Beard's idea. It became the standard way to understand that time period. However, around 1950, historians started to argue that Beard's ideas were not entirely correct. They found that voters were not always divided strictly by economic lines. Historians like Forrest McDonald argued that Beard had misunderstood the economic interests involved in writing the Constitution. McDonald found many different economic groups, not just two, which forced the delegates to compromise.

Historians later agreed that Beard's progressive view of the Constitution's creation had been disproven. They began to see the framers of the Constitution as being motivated by a desire for political unity, national economic growth, and safety, rather than just their own money interests.

Even though Beard's specific ideas about the Constitution were challenged, his legacy of looking at the economic interests of historical figures is still important today. For example, in 2003, Robert A. McGuire used advanced statistical analysis. He argued that Beard's main idea about how economic interests affected the Constitution was not far off.

Views on the Civil War

Beard's ideas about the Civil War were very popular from 1927 until the Civil Rights Era in the late 1950s. Charles and Mary Beard played down the importance of slavery, the movement to end slavery, and moral issues. They also didn't focus on states' rights or American nationalism as reasons for the war. They saw the war itself as a brief event.

The Beards emphasized that the Civil War was caused by economic issues. They believed it was not mainly about whether slavery was right or wrong. They saw it as a "struggle between two economic systems." They argued it was a "social disaster" where business owners, workers, and farmers from the North and West removed the plantation owners of the South from power in the government. They called these events a "second American Revolution."

The Beards were especially interested in what happened after the war. They believed that the business owners in the Northeast and the farmers in the West gained a lot from their victory over the Southern aristocracy. They argued that Northern business owners were able to pass laws that helped their economic plans. These laws included rules about tariffs (taxes on imported goods), banking, homesteads (land for settlers), and immigration. They believed that helping formerly enslaved people had little to do with Northern policies.

When talking about the Reconstruction Era and the Gilded Age, Beard's followers focused on greed and economic causes. They said that talk about equal rights was just a cover-up for promoting the interests of business owners in the Northeast. However, this idea was later rejected after the 1950s. Historians found that business people were not united on policy. For example, some wanted high tariffs, but others did not.

Works and Writings

- 1904 - Beard, Charles Austin, The Office of Justice of the Peace in England: In its Origin and Development

- 1913 – Beard, Charles, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States

- 1914 – Beard, Charles A. Some Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy, American Historical Review

- 1915 – Beard, Charles, Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy

- 1921 – Beard, Charles A. and Beard, Mary Ritter. History of the United States (2 vols.)

- 1923 – Beard, Charles, The Administration and Politics of Tokyo

- 1927 – Beard, Charles A. and Beard, Mary Ritter, The Rise of American Civilization

- 1932 – Beard, Charles, A Century of Progress

- 1932 – Beard, Charles, The Myth of Rugged American Individualism

- 1934 – Beard, Charles A. Written history as an act of faith. American Historical Review

- 1935 – Beard, Charles A. That noble dream, American Historical Review

- 1941 – Beard, Charles A. President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War

See also

In Spanish: Charles Beard para niños

In Spanish: Charles Beard para niños