Bruno Latour facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bruno Latour

|

|

|---|---|

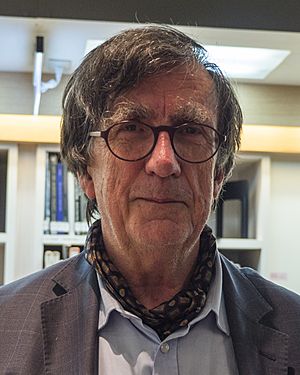

Latour in 2017

|

|

| Born | 22 June 1947 |

| Died | 9 October 2022 (aged 75) Paris, France

|

| Education | University of Tours (PhD, 1975) |

|

Notable work

|

Laboratory Life (1979) Science in Action (1987) We Have Never Been Modern (1991) Politics of Nature (1999) |

| Awards | Holberg Prize (2013) Kyoto Prize (2021) |

| Era | 21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Social constructionism Actor–network theory |

| Institutions | ORSTOM Centre de Sociologie de l'Innovation Mines ParisTech Sciences Po London School of Economics University of Amsterdam |

|

Notable ideas

|

Actor–network theory, actant, blackboxing, graphism thesis, mapping controversies, nonmodernism |

|

Influenced

|

|

Bruno Latour (born 22 June 1947 – died 9 October 2022) was a famous French thinker. He was a philosopher, an anthropologist (someone who studies human societies and cultures), and a sociologist (someone who studies how societies work).

Latour was especially known for his work in a field called Science and Technology Studies (STS). This field looks at how science and technology are connected to society. He taught at important universities like the École des Mines de Paris and Sciences Po Paris. He also taught at the London School of Economics.

Some of his most famous books include We Have Never Been Modern (1991), Laboratory Life (written with Steve Woolgar, 1979), and Science in Action (1987). Latour was a key person in developing actor–network theory (ANT). This idea suggests that both humans and non-human things (like tools, animals, or ideas) play a role in shaping the world.

Contents

About Bruno Latour

His Life and Studies

Bruno Latour came from a well-known family of winemakers in Burgundy, France. Even though his family was in the wine business, he chose to study philosophy. He was very good at it, passing tough national exams in France.

He earned his PhD degree in philosophy in 1975. Later, he became interested in anthropology. He even did fieldwork in Ivory Coast, studying how different groups of people interacted.

Latour spent many years teaching and researching at the Centre de sociologie de l'innovation in Paris. In 2006, he moved to Sciences Po, another famous university. He also helped organize popular art exhibitions in Germany, like "Iconoclash" and "Making Things Public."

Bruno Latour passed away on 9 October 2022, at the age of 75.

Awards and Honors

Latour received many important awards for his work. In 2008, he was given an honorary doctorate by the Université de Montréal. He also received France's highest honor, the Légion d'Honneur, in 2012.

In 2020, he was awarded the "Spinozalens 2020" prize in the Netherlands. Then, in 2021, he received the prestigious Kyoto Prize for his ideas on "Thought and Ethics."

Holberg Prize

On 13 March 2013, Bruno Latour won the Holberg Prize. This is a major international award given to scholars in the arts and humanities. The prize committee said that Latour had done a great job analyzing and rethinking what "modernity" means.

They noted that he challenged basic ideas like the difference between modern and pre-modern times, or between nature and society. The committee also said that Latour's work has had a big impact around the world. It influenced many fields, including history, philosophy, anthropology, and art.

Key Ideas and Books

Bruno Latour wrote several influential books that changed how people thought about science and society.

Laboratory Life

One of Latour's early and very important books was Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts, published in 1979 with Steve Woolgar. In this book, they studied scientists working in a neuroendocrinology lab.

They found that science isn't always a simple, step-by-step process. Instead, scientists often have to make decisions about which data to keep or throw out. Latour and Woolgar suggested that scientific facts are not just "discovered" but are also "built" or "constructed" within the lab. This means that the tools, discussions, and decisions made by scientists all play a role in creating what we call scientific knowledge.

The Pasteurization of France

In this book, published in 1988, Latour looked at the life of the famous French scientist Louis Pasteur. Pasteur discovered microbes and developed pasteurization.

Latour explored how Pasteur's ideas were accepted (or not accepted) by society. He showed that it wasn't just about experiments and evidence. Social reasons, like how people communicated or how powerful certain groups were, also played a big part in whether Pasteur's theories were believed.

Aramis, or, The Love of Technology

This book focuses on a failed public transport project in Paris called Aramis. It was supposed to be a high-tech automated subway system. Latour studied why the project didn't work out.

He argued that the technology failed not because one person stopped it. Instead, it failed because the different groups involved couldn't agree or adapt to new situations. In this book, Latour explained more about his actor-network theory. This theory suggests that technology, like the Aramis system, is not just a machine. It's a mix of people, ideas, and objects all working together (or not working together).

We Have Never Been Modern

Published in 1991, We Have Never Been Modern is one of Latour's most famous works. In this book, he challenged the idea that modern society is completely separate from the past.

Latour argued that we have never truly been "modern" in the way we often think. He believed that modern thinking tries to separate things too much, like nature from society, or facts from values. He suggested that these things are always connected. Latour promoted a "nonmodern" way of thinking. This approach tries to see how everything is linked, rather than trying to keep things separate.

Pandora's Hope

In Pandora's Hope (1999), Latour continued to explore how scientific knowledge is created. He used different stories and examples, like his work with soil scientists in the Amazon rainforest.

He showed that understanding science means looking closely at the small details of how scientists actually work. Latour also discussed how science is connected to politics. He talked about issues like global warming and diseases, showing how scientific debates can be influenced by political and social factors.

Reassembling the Social

In Reassembling the Social (2005), Latour looked at how we understand society. He suggested that when we study people, we should pay close attention to what they say makes them act. For example, if someone says they were inspired by God, we should take that seriously.

Latour believed that there isn't just one single "reality" or one way the world works. Instead, there are many different "worlds" or ways of seeing things, depending on what motivates people. He encouraged researchers to understand these different viewpoints without trying to fit them into one simple explanation.

See also

In Spanish: Bruno Latour para niños

In Spanish: Bruno Latour para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |