Alfred North Whitehead facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alfred North Whitehead

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 15 February 1861 Ramsgate, England

|

| Died | 30 December 1947 (aged 86) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Education | Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A., 1884) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | |

| Academic advisors | Edward Routh |

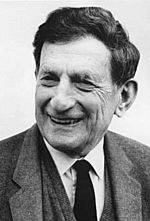

| Doctoral students |

|

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

Process philosophy Process theology |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

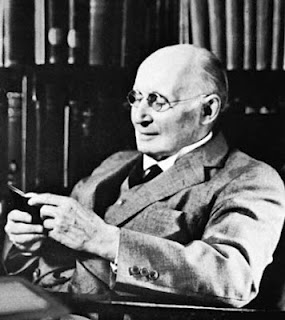

Alfred North Whitehead (born February 15, 1861 – died December 30, 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He is famous for developing "process philosophy". This idea suggests that everything in the world is constantly changing and connected.

Whitehead's ideas are now used in many areas. These include ecology (the study of how living things interact with their environment), theology (the study of religion), education, physics, biology, economics, and psychology.

Early in his career, Whitehead focused on mathematics, logic, and physics. His most well-known work from this time is Principia Mathematica. He wrote this three-volume book (1910–1913) with his former student, Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica is considered a very important book in mathematical logic.

Later, in the 1910s and 1920s, Whitehead shifted his focus. He moved from mathematics to the philosophy of science, and then to metaphysics. Metaphysics is the study of the basic nature of reality. He created a new way of thinking about reality. It was very different from most Western philosophy.

Whitehead believed that reality is made of processes (things happening) rather than solid objects. He argued that these processes are defined by how they relate to other processes. This was different from the idea that reality is just separate bits of matter. Today, his philosophical works, especially Process and Reality, are key texts for process philosophy.

Whitehead's process philosophy teaches that "we must see the world as a web of connected processes." We are part of this web. This means our choices and actions affect everything around us. Because of this, his ideas are very useful for understanding ecological civilization and environmental ethics.

Contents

Life Story

Growing Up and School

Alfred North Whitehead was born in Ramsgate, England, in 1861. His father and grandfather were both successful school headmasters. His mother was Maria Sarah Buckmaster.

Whitehead went to Sherborne School, a well-known English school. He was good at sports and mathematics. He was also the head student of his class.

In 1880, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge. He studied mathematics there. He earned his degree in 1884. His main project was about James Clerk Maxwell's book on electricity and magnetism.

His Career Journey

Whitehead became a teacher at Trinity College in 1884. He taught mathematics and physics until 1910. During this time, he wrote A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898). He also worked with his former student, Bertrand Russell, on Principia Mathematica.

In 1910, Whitehead left Trinity College and moved to London. He found a job teaching applied mathematics at University College London.

In 1914, he became a professor of applied mathematics at Imperial College London.

After 1918, Whitehead took on more leadership roles. He became dean of the Faculty of Science at the University of London. He also joined the University of London's Senate. He helped create a new history of science department. He also worked to make the school more open to students from all backgrounds.

Towards the end of his time in England, Whitehead started focusing on philosophy. Even without formal training, his philosophical work became highly respected. He published The Concept of Nature in 1920. He was also president of the Aristotelian Society from 1922 to 1923.

Moving to the United States

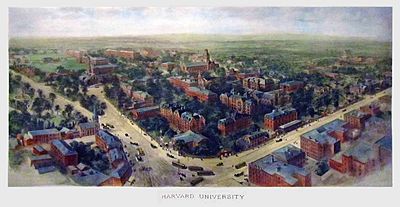

In 1924, when he was 63, Whitehead was invited to teach at Harvard University in the United States. He and his wife lived there for the rest of their lives.

At Harvard, Whitehead wrote his most important philosophical books. In 1925, he wrote Science and the Modern World. This book offered new ideas that challenged common ways of thinking about science. His lectures from 1927 to 1928 became the book Process and Reality (1929). This book is often compared to important works by Immanuel Kant.

Family Life and Passing Away

In 1890, Whitehead married Evelyn Wade. They had a daughter, Jessie, and two sons, Thomas and Eric. Their son Eric died at age 19 during World War I.

Whitehead retired from Harvard in 1937. He stayed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until he passed away on December 30, 1947.

After his death, Whitehead's family followed his wishes and destroyed all his personal papers. This means many details of his life are not known. He was also very private and did not write many personal letters.

Mathematics and Logic

Whitehead wrote many articles and three main books on mathematics. These were A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), Principia Mathematica (1910–1913), and An Introduction to Mathematics (1911).

The first two books were for professional mathematicians. An Introduction to Mathematics was for a wider audience. It covered the history of mathematics and its philosophical ideas. Principia Mathematica is seen as one of the most important works in mathematical logic of the 20th century.

Whitehead's idea of "extensive abstraction" is also important. It helped create a field called "mereotopology". This field describes how parts relate to wholes in space.

About A Treatise on Universal Algebra

In this 1898 book, universal algebra meant studying the basic rules of algebra. It was not about specific examples. Whitehead gave credit to William Rowan Hamilton and Augustus De Morgan for starting this field.

At the time, new types of algebra showed a need to go beyond simple multiplication rules. One reviewer said the book's main idea was to compare different algebraic structures. Another noted its remarkable unity, given its many topics.

The book looked at ideas from Hermann Grassmann and George Boole. Whitehead hoped to create a single way to understand different algebras. However, he did not finish the second volume of the book.

About Principia Mathematica

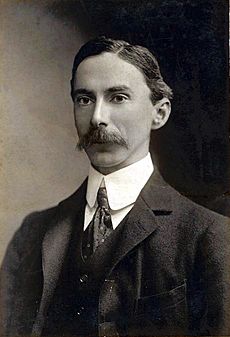

Principia Mathematica (1910–1913) is Whitehead's most famous math book. He wrote it with Bertrand Russell. It is considered one of the most important math books of the 20th century. It was even ranked 23rd on a list of top 100 English non-fiction books.

The goal of Principia Mathematica was to create a set of basic rules (called axioms) and logic steps. From these, all mathematical truths could, in theory, be proven. Whitehead and Russell worked at such a basic level that it took them until page 86 of Volume II to prove that 1+1=2! They jokingly added, "The above proposition is occasionally useful."

They thought the book would take one year to write, but it took ten. It was over 2,000 pages long. It was so specialized that it lost money when first published. But today, almost every major academic library has a copy.

The book's long-term impact is mixed. Kurt Gödel later showed that no single set of rules can prove all mathematical truths. So, Principia Mathematica could not fully achieve its goal. However, Gödel's discovery relied on their work. The book also made modern mathematical logic popular. It showed important links between logic, how we gain knowledge, and the nature of reality.

About An Introduction to Mathematics

Unlike his other math books, An Introduction to Mathematics (1911) was for a wider audience. It explored what mathematics is, how its parts connect, and how it applies to nature.

The book tried to show how mathematics is unified and connected. It also looked at how math and philosophy, language, and physics influence each other. This book, though not widely read, hinted at some of Whitehead's later philosophical ideas.

Ideas on Education

Whitehead cared deeply about improving education at all levels. He was part of a committee in 1921. This group looked at the UK's education system and suggested changes.

His main work on education is The Aims of Education and Other Essays (1929). In one essay, he warned against teaching "inert ideas." These are facts that are disconnected and have no real-life use. He said, "education with inert ideas is not only useless: it is, above all things, harmful."

Instead of teaching many small facts, Whitehead suggested teaching a few important ideas. Students could then connect these ideas to different areas of knowledge. They could see how these ideas apply to real life. For Whitehead, education should be about connecting ideas and values. It should help students gain wisdom and link different subjects.

To make this happen, Whitehead said schools should rely less on standardized tests for entrance. He believed that schools should create their own lessons for their students. Otherwise, education would become stagnant.

Most importantly, Whitehead stressed the value of imagination and free thinking in education. He famously said, "knowledge does not keep any better than fish." This means disconnected facts are useless. All knowledge must be used in a creative way by students. Otherwise, it just becomes useless trivia.

Philosophy and Reality

Whitehead did not start his career as a philosopher. He had no formal training in philosophy beyond his college studies. But he was very interested in philosophy and metaphysics. Metaphysics is the study of the basic nature of the universe and existence.

By the 1920s, when Whitehead began writing about metaphysics, it was not a popular topic. Many thought that creating big philosophical systems was a waste of time. This was because they could not be tested by science.

Whitehead disagreed. He believed that scientists and philosophers always make assumptions about how the universe works. But these assumptions are often not examined. He argued that people need to keep rethinking their basic ideas about the universe. This is how philosophy and science can make real progress. So, Whitehead saw metaphysical study as essential for good science and philosophy.

One idea Whitehead thought was wrong was the Cartesian idea. This idea says reality is made of separate bits of matter. Whitehead rejected this. He believed reality is made of events or "processes." These events are connected and depend on each other. He also thought that the most basic parts of reality are like experiences. He used the word "experience" very broadly. Even things like electron collisions have some kind of "experience." This was different from Descartes' idea of separate material and mental existences. Whitehead called his system "philosophy of organism," but it became known as "process philosophy."

Whitehead's philosophy was very original. It quickly gained attention. After publishing The Concept of Nature in 1920, he led the Aristotelian Society. Henri Bergson even called him "the best philosopher writing in English." His ideas were so impressive that Harvard University invited him to be a philosophy professor in 1924.

However, Whitehead's ideas were not always widely understood. His philosophical writings are considered very difficult. Even professional philosophers found them hard to follow.

One theologian, Shailer Mathews, said of Whitehead's 1926 book Religion in the Making: "It is infuriating... to read page after page of relatively familiar words without understanding a single sentence."

Despite this, many at the University of Chicago's Divinity School saw the importance of Whitehead's work. In 1927, they invited Henry Nelson Wieman, an expert on Whitehead, to explain his ideas. Wieman's lecture was so good that he was hired. For about 30 years, Chicago's Divinity School was closely linked to Whitehead's thought.

Process and Reality has been called "the most impressive single metaphysical text of the twentieth century." But it is not widely read or understood. This is partly because it challenges common ideas about the universe. However, by doing so, Whitehead predicted many scientific and philosophical problems of the 21st century. He also offered new solutions.

Whitehead's View of Reality

Whitehead believed that the scientific idea of "matter" was misleading. He thought it did not truly describe the nature of things.

He saw problems with the idea of "basic, unchanging matter." First, it hides the importance of change. If we think of a rock or a person as always being the "same" thing, we miss that nothing ever stays the same. For Whitehead, change is fundamental. He stressed that "all things flow."

Whitehead thought that ideas like "quality" and "matter" were problematic. These old ideas do not explain change well. They also ignore the active nature of the world's basic elements. They are useful abstractions, but not the true building blocks. For example, a person is not one solid thing. Instead, they are a series of overlapping events. People change all the time, even if it's just by aging another second and having a new experience. These "occasions of experience" are distinct but connected. They form what Whitehead called a "society" of events. When people think of lasting objects as the most real things, they are mistaking an abstract idea for the concrete reality. Whitehead called this the "fallacy of misplaced concreteness."

To explain it another way, we often think of a thing or person as having an "unchanging core." This core defines what they "really are." We see things as fundamentally the same over time, with changes being secondary. But in Whitehead's view, the only truly existing things are separate "occasions of experience." These overlap in time and space and together make up the lasting person or thing. What we call "the essence of a thing" is just a general idea of its most important features over time. Identities do not define people; people define identities. Everything changes constantly. Thinking of anything as having an "unchanging essence" misses that "all things flow."

Whitehead noted that language itself can make us think in a materialistic way. It is hard to avoid this in everyday talk. We cannot give a different name to every moment of a person's life. It is easy to think of people and objects as staying the same. But Whitehead said we should realize that "material substances" are just convenient descriptions of a continuous flow of processes. A ten-year-old is very different from a thirty-year-old. Whitehead argued that a person is not even the same from one second to the next.

Another problem with materialism is that it hides the importance of relations. It sees every object as separate. Each object is just a clump of matter that is only externally connected to other things. But for Whitehead, relationships are primary. A student wrote that Whitehead said: "Reality applies to connections, and only relatively to the things connected." This means things are real because they relate to other things. If something had no effect on anything else, it would not truly exist. Relationships are not secondary; they are what a thing is.

However, an entity is not just the sum of its relationships. It also responds to them. For Whitehead, creativity is the basic principle of existence. Every entity, whether a human, a tree, or an electron, has some freedom in how it responds. It is not fully controlled by strict laws. Most entities do not have consciousness. Just as human actions cannot always be predicted, neither can a tree's roots or an electron's movement. This unpredictability is not due to a lack of understanding. It is because of the basic creativity of all entities.

The other side of creativity is that every entity is limited by its connections. Each entity must fit into the world around it. Freedom always exists within limits. But an entity's unique nature comes from how it chooses to respond to the world within those limits.

In short, Whitehead rejected the idea of separate, unchanging bits of matter as the basis of reality. He believed reality is made of connected events in a process. He saw reality as dynamic "becoming" rather than static "being." All physical things change and evolve. Unchanging "essences" like matter are just ideas taken from the real, changing events that make up the world.

How We Perceive Things

Whitehead's ideas about reality meant he needed a new way to describe perception. This new way could not be limited to living, thinking beings. He created the term "prehension." This word comes from Latin, meaning "to seize." It describes a kind of perception that can be conscious or unconscious. It applies to people as well as electrons.

"Prehension" also shows Whitehead's rejection of "representative perception." This idea says the mind only has private ideas about other things. For Whitehead, "prehension" means the perceiver actually takes in parts of the perceived thing. So, entities are shaped by their perceptions and relationships.

Whitehead described two ways of perceiving. One is causal efficacy (or "physical prehension"). This is "the experience dominating the primitive living organisms." It is a sense of being influenced by the environment. It is not filtered by the senses. The other is presentational immediacy (or "conceptual prehension"). This is what we usually call "pure sense perception." It is not influenced by any interpretation, even unconscious ones. It is just how things appear, which might sometimes be misleading.

In more complex organisms, like humans, these two ways combine. Whitehead called this "symbolic reference." It links how things appear with their causes. This process is so automatic that people and animals do it without thinking. For example, a person sees a colored shape and immediately thinks it is a chair. An artist, however, might just see the color and shape. This shows that most people categorize objects by habit. Animals do the same. A dog would immediately jump on a chair. This means causal relationships are stronger in simpler minds. Sense perceptions show a higher level of thinking.

Evolution and Value

Whitehead believed that when we ask about the basic facts of existence, we cannot ignore questions about value and purpose. This is clear in his thoughts on how life began.

He noted that "life is comparatively deficient in survival value." Humans live about a hundred years, but rocks can last for millions. So, why did complex life forms ever evolve? Whitehead joked that they "certainly did not appear because they were better at that game than the rocks around them." He observed that higher life forms actively change their environment. He thought this was to achieve three goals: living, living well, and living better. In other words, Whitehead saw life as aiming to increase its own satisfaction. Without such a goal, he found the rise of life hard to understand.

For Whitehead, nothing is completely inert matter. Everything has some freedom or creativity, no matter how small. This allows things to be partly self-directed. The term "panexperientialism" describes Whitehead's view. It means all entities experience, but it is different from panpsychism, which says all matter has consciousness.

God

Whitehead's idea of God is different from traditional religious views. He famously criticized the Christian idea of God. He said the Church gave God qualities that belonged to a powerful ruler. Whitehead believed God is not just about power.

For Whitehead, God is not necessarily tied to religion. He saw God as a necessary part of his metaphysical system. This system needed an order among possibilities. This order allowed for new things to happen in the world. It also gave a purpose to all entities. Whitehead called these ordered possibilities the primordial nature of God.

Whitehead was also interested in religious experience. This led him to think about God's second nature, the consequent nature. Whitehead's idea of God as having two parts has led to new ways of thinking in theology.

The primordial nature is "the unlimited conceptual realization of the absolute wealth of potentiality." This means it is the unlimited possibility of the universe. This part of God is eternal and unchanging. It gives entities in the universe possibilities to become real. Whitehead also called this aspect "the lure for feeling, the eternal urge of desire." It pulls entities toward possibilities that have not yet happened.

God's consequent nature, however, is always changing. It is God's reception of the world's activities. Whitehead said, "[God] saves the world as it passes into the immediacy of his own life." This means God saves and values all experiences forever. These experiences then change how God interacts with the world. So, God is truly changed by what happens in the world. This gives the actions of creatures an eternal meaning.

Whitehead saw God and the world as completing each other. Entities in the world are changing. They long for a lasting quality that only God can provide by taking them into God's self. This then changes God and affects the rest of the universe. On the other hand, God is lasting but needs to become real and change. Alone, God is just endless possibilities. God needs the world to make these possibilities real. God gives creatures lasting meaning, while creatures give God reality and change.

These ideas inspired a movement called process theology. This is a lively school of thought in theology that is still active today.

Religion

For Whitehead, the core of religion was personal. He believed that life is an inner experience first, before it relates to others. His most famous quote on religion is: "religion is what the individual does with his own solitariness... and if you are never solitary, you are never religious." Whitehead saw religion as a system of truths that changed a person's character. He noted that while religion is often good, it is not always good. He called the idea that it is always good a "dangerous delusion."

However, while religion begins in solitude, Whitehead saw it as needing to expand beyond the individual. In his process metaphysics, relationships are key. He wrote that religion requires understanding "the value of the objective world." This world is a community made from the connections between individuals. Meaning and value do not exist for one person alone. They exist only within the universal community. Whitehead wrote that each entity "can find no such value till it has merged its individual claim with that of the objective universe. Religion is world loyalty." This means the individual and social parts of religion depend on each other.

Whitehead also described religion as "an ultimate craving to infuse into the insistent particularity of emotion that non-temporal generality which primarily belongs to conceptual thought alone." This means religion takes strong emotions and places them within a system of general truths about the world. This helps people understand their wider meaning. For Whitehead, religion was a bridge between philosophy and the feelings of a society. It makes philosophy useful in the daily lives of ordinary people.

Influence

Isabelle Stengers noted that Whitehead's followers include philosophers and theologians. His ideas have also reached people in many other fields. These include ecology, feminism, and the sciences of education. In recent decades, more people have paid attention to Whitehead's work. Interest has grown in Europe and China. It comes from fields like physics, biology, education, economics, and psychology.

Early followers of Whitehead were mainly at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Henry Nelson Wieman started this interest. Professors like Wieman and Charles Hartshorne made Whitehead's philosophy very important there. They taught many scholars, including John B. Cobb.

While interest in Whitehead has lessened at Chicago, Cobb continued his work. He started teaching at Claremont School of Theology in 1958. In 1973, he founded the Center for Process Studies with David Ray Griffin. Because of Cobb, Claremont is still strongly linked to Whitehead's process thought.

Whitehead's ideas are growing quickly in China. To deal with modernization, China is mixing ideas from Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism with Whitehead's philosophy. They are creating an "ecological civilization." The Chinese government has supported 23 university centers to study Whitehead's philosophy. Books by John Cobb and David Ray Griffin are becoming required reading for Chinese students. Cobb believes China's interest comes from Whitehead's focus on how humans and nature depend on each other. Also, his emphasis on teaching values in education, not just facts, is appealing.

Overall, Whitehead's influence is hard to describe. In English-speaking countries, his main works are not widely studied outside of Claremont. His influence is smaller and spread out. It often comes through the work of his students rather than his own books. For example, Whitehead taught Bertrand Russell and Willard Van Orman Quine. Both are important in analytic philosophy. This is the main type of philosophy in English-speaking countries.

Whitehead also has admirers in Continental philosophy. The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze called Whitehead "the last great Anglo-American philosopher." The French sociologist Bruno Latour even called him "the greatest philosopher of the 20th century."

However, these views are not common. Whitehead is not seen as very influential in the most dominant philosophical schools. This might be because his ideas about reality seem unusual. For example, he said that matter is an abstraction. Also, his philosophy includes ideas about God. Or it might be because metaphysics itself is seen as old-fashioned. His writing style is also very difficult.

Process Philosophy and Theology

Historically, Whitehead's work has been most important in American progressive theology. Charles Hartshorne was a key early supporter of Whitehead's ideas in theology. He was Whitehead's teaching assistant at Harvard in 1925. Hartshorne is known for developing Whitehead's process philosophy into a full process theology. Other important process theologians include John B. Cobb and David Ray Griffin.

Process theology often highlights God's relational nature. Instead of seeing God as emotionless, process theologians see God as "the fellow sufferer who understands." God is the being most affected by events in time. Hartshorne argued that we would not praise a human ruler who was unaffected by his people's joys or sorrows. So why would this be a good quality in God? Instead, God is the being most affected by the world. This means God can respond to the world in the best way. However, process theology has many different forms. Some, like C. Robert Mesle, even propose a "process naturalism"—a process theology without God.

Process theology is hard to define because its followers are so diverse. John B. Cobb, for example, has written books on biology and economics. Roland Faber and Catherine Keller combine Whitehead's ideas with other modern theories. Charles Birch was both a theologian and a geneticist.

Process philosophy is even harder to define than process theology. In practice, the two fields often overlap. The 32-volume series on constructive postmodern thought shows the wide range of areas where process philosophers work. These include physics, ecology, medicine, and psychology.

American pragmatism has also had a close link with process philosophy. Whitehead himself admired William James and John Dewey. Charles Hartshorne helped edit the papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, a founder of pragmatism. Today, Nicholas Rescher is a philosopher who supports both process philosophy and pragmatism.

Whitehead has also influenced philosophers like Gilles Deleuze, Isabelle Stengers, and Bruno Latour.

Science

Scientists influenced by Whitehead's work in the early 20th century include chemist Ilya Prigogine, biologist Conrad Hal Waddington, and geneticists Charles Birch and Sewall Wright.

In physics, Whitehead's theory of gravitation was different from Albert Einstein's general relativity. It has been criticized. Whitehead's view is now considered outdated. This is because of the discovery of gravitational waves. These waves show that space is not as flat as Whitehead assumed. So, Whitehead's ideas about the universe are now seen as a local approximation. However, even though Whitehead did not focus much on quantum theory, his ideas about processes have attracted some physicists in that field. Henry Stapp and David Bohm are among those influenced by Whitehead.

In the 21st century, Whitehead's ideas still inspire scientists. Books like Physics and Whitehead (2004) and Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (2004) offer Whiteheadian approaches to physics. Beyond Mechanism (2013) and Science Set Free (2012) apply his ideas to biology.

Ecology, Economy, and Sustainability

One of the most promising uses of Whitehead's ideas recently has been in ecological civilization, sustainability, and environmental ethics.

Whitehead's ideas about value fit well with an ecological view. Many see his work as a good alternative to the old mechanistic worldview. It offers a detailed picture of a world made of connected relationships.

John B. Cobb has led this work. His book Is It Too Late? A Theology of Ecology (1971) was one of the first books on environmental ethics. Cobb also wrote For the Common Good (1989) with Herman Daly. This book applied Whitehead's ideas to economics. It won an award for ideas that improve world order. Cobb also wrote Sustaining the Common Good (1994). This book challenged economists' strong belief in constant growth.

Education

Whitehead is widely known for his influence on education theory. His philosophy led to the creation of the Association for Process Philosophy of Education (APPE). This group published a journal on process philosophy and education. Whitehead's theories also led to new ways of learning and teaching.

One such model is the ANISA model. It tried to fix the lack of understanding about human nature in education systems. Its creators said that education needed a clear idea of the people it was meant for.

Another model is the FEELS model, used in China. "FEELS" stands for Flexible-goals, Engaged-learner, Embodied-knowledge, Learning-through-interactions, and Supportive-teacher. It helps understand and evaluate school lessons. It assumes education's purpose is to "help a person become whole."

Whitehead's education philosophy also has support in Canada. The University of Saskatchewan has a Process Philosophy Research Unit. They have held conferences on process philosophy and education.

Recent books that build on Whitehead's education philosophy include: Modes of Learning (2012) by George Allan; The Adventure of Education (2009) by Adam Scarfe; and Educating for an Ecological Civilization (2017).

Business Administration

Whitehead has also influenced the philosophy of business administration and organizational theory. This has led to focusing on how events (not just static things) affect organizations. Mark Dibben applies Whitehead's ideas to management. He sees life as "perpetually active experiencing." He has written books on "applied process thought."

Margaret Stout and Carrie M. Staton have written about Whitehead's influence on Mary Parker Follett. Follett was a pioneer in organizational theory. Stout and Staton believe both Whitehead and Follett shared a view that "becoming is a relational process." They saw differences as connected but unique. The goal of becoming was to bring differences into harmony.

Political Ideas

Whitehead's political views sometimes seem like libertarianism. However, many scholars believe his work supports the social liberalism of the New Liberal movement. This movement was important during Whitehead's life.

Primary Works

Books written by Whitehead, listed by date of publication:

- A Treatise on Universal Algebra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898. ISBN: 1-4297-0032-7.

- The Axioms of Descriptive Geometry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907.

- with Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910.

- An Introduction to Mathematics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911.

- with Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica, Volume II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1912.

- with Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913.

- The Organization of Thought Educational and Scientific. London: Williams & Norgate, 1917.

- An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1919.

- The Concept of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920.

- The Principle of Relativity with Applications to Physical Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922.

- Science and the Modern World. New York: Macmillan Company, 1925.

- Religion in the Making. New York: Macmillan Company, 1926.

- Symbolism, Its Meaning and Effect. New York: Macmillan Co., 1927.

- Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Macmillan Company, 1929.

- The Aims of Education and Other Essays. New York: Macmillan Company, 1929.

- The Function of Reason. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1929.

- Adventures of Ideas. New York: Macmillan Company, 1933.

- Nature and Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934.

- Modes of Thought. New York: MacMillan Company, 1938.

- "Mathematics and the Good." In The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, edited by Paul Arthur Schilpp, 666–681. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1941.

- "Immortality." In The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, edited by Paul Arthur Schilpp, 682–700. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1941.

- Essays in Science and Philosophy. London: Philosophical Library, 1947.

- with Allison Heartz Johnson, ed. The Wit and Wisdom of Whitehead. Boston: Beacon Press, 1948.

- Paul A. Bogaard and Jason Bell, eds. The Harvard Lectures of Alfred North Whitehead, 1924–1925: Philosophical Presuppositions of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

See also

In Spanish: Alfred North Whitehead para niños

In Spanish: Alfred North Whitehead para niños

- Great refusal

- Pancreativism

- Relationalism

- Speculative realism

- Whitehead's point-free geometry

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |