Hermann Grassmann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hermann Günther Grassmann

|

|

|---|---|

Hermann Günther Grassmann

|

|

| Born | 15 April 1809 |

| Died | 26 September 1877 (aged 68) Stettin, German Empire

|

| Alma mater | University of Berlin |

| Known for |

|

| Awards | PhD (Hon): University of Tübingen (1876) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Stettin Gymnasium |

Hermann Günther Grassmann (born April 15, 1809 – died September 26, 1877) was a German polymath. This means he was an expert in many different subjects. During his life, people knew him mostly as a linguist, someone who studies languages. Today, he is also famous as a mathematician. He was also a physicist, a general scholar, and even a publisher. His important math work was not widely noticed until he was in his sixties. He developed ideas that were far ahead of his time, like the concept of a vector space, which is a key part of modern math.

About Hermann Grassmann

Hermann Grassmann was the third of 12 children. His father, Justus Günter Grassmann, was a Christian minister. He also taught math and physics at a high school called the Stettin Gymnasium, where Hermann went to school.

Hermann was not a top student at first. But he did very well on the exams to get into universities in Prussia. In 1827, he started studying theology at the University of Berlin. He also took classes in old languages, philosophy, and literature. It seems he did not take math or physics classes there.

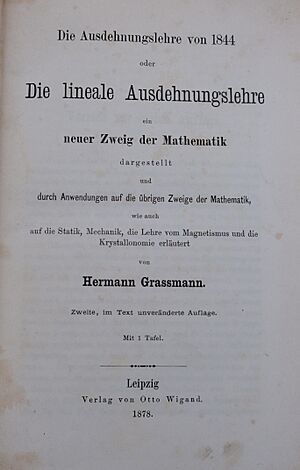

Even without university training in math, it was the subject he loved most. After finishing his studies in Berlin, he returned to Stettin in 1830. He spent a year getting ready for exams to teach math in a high school. He passed, but only well enough to teach at lower levels. Around this time, he made his first big math discoveries. These led to his important ideas in his 1844 paper, Die lineale Ausdehnungslehre, ein neuer Zweig der Mathematik. This translates to "The Theory of Linear Extension, a New Branch of Mathematics." He later updated this work in 1862.

In 1834, Grassmann started teaching math in Berlin. A year later, he went back to Stettin. He taught math, physics, German, Latin, and religious studies at a new school. Over the next four years, he passed more exams. This allowed him to teach math, physics, chemistry, and mineralogy at all high school levels.

In 1847, he became a "head teacher." In 1852, he took over his late father's job at the Stettin Gymnasium. This gave him the title of Professor. In 1847, he asked to be considered for a university job. The Ministry of Education asked a famous mathematician, Ernst Kummer, for his opinion. Kummer said Grassmann's work had "good material expressed in a deficient form." This meant his ideas were good, but hard to understand. Kummer's report stopped Grassmann from getting a university job. Many important people of his time did not understand how valuable his math was.

Around 1848–49, during a time of political trouble in Germany, Hermann and his brother Robert started a newspaper. It was called Deutsche Wochenschrift für Staat, Kirche und Volksleben. They wanted Germany to become one country with a king who followed rules. Hermann later left the newspaper because he disagreed with its political ideas.

Grassmann had eleven children, and seven of them lived to be adults. One of his sons, Hermann Ernst Grassmann, became a math professor.

His Work in Mathematics

One of the exams Grassmann took required him to write an essay about how ocean tides work. In 1840, he wrote this essay. He used ideas from other scientists but explained them using his own new methods, which were like what we now call vector methods. This essay, published much later, was the first time ideas like linear algebra and the idea of a vector space appeared. He continued to develop these methods in his main work, the Ausdehnungslehre.

In 1844, Grassmann published his most important math book. It is often called the Ausdehnungslehre, which means "theory of extension" or "theory of expanding things." This book suggested a new way to think about all of mathematics. It started with very general ideas. Grassmann then showed that if you put geometry into his new math system, the number three (like our three dimensions of space) is not special. He showed that math could work in any number of dimensions.

A historian named Fearnley-Sander described Grassmann's ideas about linear algebra. He said that Grassmann had the idea of a linear space (or vector space) long before others. Grassmann didn't use the exact words we use today, but he clearly understood the concept. He started with basic "units" and showed how to combine them. He explained how to add them and multiply them by numbers, just like we do in modern linear algebra. He also defined ideas like linear independence, span, dimension, and how to combine or separate these spaces. Fearnley-Sander said that few people have created a whole new subject in math by themselves as Grassmann did.

Grassmann's book also introduced the exterior product. This is a key operation in a math system now called exterior algebra. At that time, the only math system with clear rules was Euclidean geometry. The idea of an abstract algebra (a math system with its own rules) was not yet defined. Later, in 1878, another mathematician named William Kingdon Clifford combined Grassmann's ideas with William Rowan Hamilton's quaternions.

Grassmann's 1844 book was very new and ahead of its time. When he submitted it for a professorship, the ministry asked for an opinion from Ernst Kummer. Kummer said the ideas were good but hard to understand. This meant Grassmann did not get the university job. For the next 10 years, Grassmann wrote other works using his theory. He hoped these examples would make others take his ideas seriously. These included a paper on electromagnetism and several papers on algebraic curves and surfaces.

In 1846, another mathematician, Möbius, invited Grassmann to a competition. The challenge was to create a way to do geometry without using coordinates or measurements. Grassmann's entry won the competition (it was the only one). However, Möbius, one of the judges, criticized Grassmann for introducing new ideas without explaining them clearly.

In 1853, Grassmann published a theory about how colors mix. His four color laws are still taught today as Grassmann's laws. Grassmann also wrote about crystallography (the study of crystals), electromagnetism, and mechanics (how things move).

In 1861, Grassmann helped set the stage for how we define numbers today in his book Lehrbuch der Arithmetik. In 1862, he published a completely rewritten second edition of his main math book. He hoped it would finally get his theory of extension recognized. This new book, Die Ausdehnungslehre: Vollständig und in strenger Form bearbeitet, was much clearer. It was written in a way that looks like modern math textbooks. But it still did not become popular.

His Work in Languages

Grassmann's math ideas only started to become well-known near the end of his life. Thirty years after his first math book was published, the publisher wrote to him. They said his book had been out of print for a while. Because it hardly sold any copies, about 600 books were used as waste paper in 1864! Only a few copies were left.

Because his math work was not appreciated, Grassmann lost touch with other mathematicians. He also lost interest in geometry. In the last years of his life, he focused on studying old languages, especially Sanskrit (an ancient language from India). He wrote books on German grammar, collected folk songs, and learned Sanskrit. He created a huge 2,000-page dictionary for Sanskrit. He also translated the Rigveda, an important ancient Indian text, which was over 1,000 pages long. Today, when people study the Rigveda, they often use Grassmann's work. A third edition of his dictionary was published in 1955.

Grassmann also noticed a special sound rule that exists in both Sanskrit and Greek. This rule is now called Grassmann's law in his honor.

People recognized his work in languages during his lifetime. He was chosen to be part of the American Oriental Society. In 1876, he received an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Tübingen.

See also

In Spanish: Hermann Grassmann para niños

In Spanish: Hermann Grassmann para niños

- Ampère's force law

- Bra–ket notation (Grassmann's work was an early step towards this)

- Geometric algebra

- Multilinear algebra

- List of things named after Hermann Grassmann