Charles Sanders Peirce facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Sanders Peirce

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 10, 1839 Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | April 19, 1914 (aged 74) Milford, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Era | Late modern philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Pragmatism Pragmaticism |

| Institutions | Johns Hopkins University |

| Notable students |

List

|

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Influences

|

|

| Signature | |

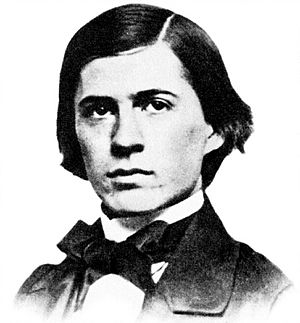

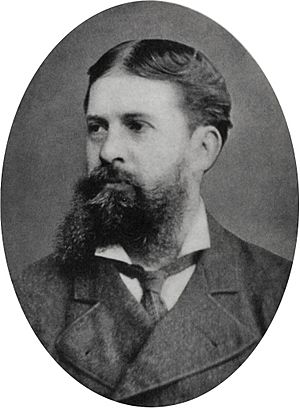

Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced PURSS; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an amazing American thinker. He was a philosopher, a logician (someone who studies how we reason), a mathematician, and a scientist. Some people even call him "the father of pragmatism".

Peirce made big contributions to logic. He is also known for starting the study of semiotics. This is the study of how language, signs, and symbols get their meaning. As early as 1886, he figured out that logical operations could be done using electrical switches. This same idea was used many years later to create digital computers.

In mathematics, Peirce worked on linear algebra, matrices, and different types of geometry. He also studied topology, graphs, and the famous four-color problem. In 1934, a philosopher named Paul Weiss called Peirce "the most original and versatile of American philosophers."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Charles Sanders Peirce was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father, Benjamin Peirce, was a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard University. Charles grew up in a very smart family!

He went to Harvard and earned two degrees: a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts. He also got a Bachelor of Science degree from the Lawrence Scientific School in 1863.

At Harvard, he became good friends with people like William James. However, one of his teachers, Charles William Eliot, didn't think highly of Peirce. This was important because Eliot later became the President of Harvard. He stopped Peirce from getting a job at the university many times.

From his late teens, Peirce had a painful nerve condition. This condition might have made him feel isolated later in his life.

Early Career and Work

Between 1859 and 1891, Peirce worked for the United States Coast Survey. He mainly focused on geodesy (measuring the Earth's shape) and gravimetry (measuring gravity). He improved how pendulums were used to find small changes in the Earth's gravity. This job also meant he didn't have to fight in the American Civil War.

The Survey sent him to Europe five times. One trip was in 1871 to watch a solar eclipse. From 1869 to 1872, he also worked at Harvard's astronomical observatory. There, he did important work on how bright stars are and the shape of the Milky Way. In 1877, he became a member of the National Academy of Sciences. He also suggested a new way to define the meter using light waves.

From 1883 to 1909, Peirce wrote many entries for Century Dictionary. These entries covered philosophy, logic, science, and other topics. In 1891, he left the Coast Survey.

Teaching at Johns Hopkins

In 1879, Peirce became a lecturer in logic at Johns Hopkins University. He published a book called Studies in Logic by Members of the Johns Hopkins University (1883). This book included works by him and his students. This was the only university teaching job Peirce ever had.

Sadly, Peirce's personal life caused some difficulties, leading to his dismissal from the university in 1884. He tried to get other university jobs but wasn't successful. After his first marriage ended, he married Juliette. He never had any children.

Later Years and Struggles

In 1887, Peirce used some money he inherited to buy a large piece of land near Milford, Pennsylvania. He hoped it would make money, but it never did. He remodeled an old farmhouse there, and they called their home "Arisbe". They lived there for the rest of their lives. Charles wrote a lot, but much of it was never published.

Living beyond their means led to serious financial and legal problems. He faced financial and legal problems later in life. Luckily, some friends and family helped him pay his debts and taxes.

Peirce did some science and engineering consulting. He also wrote many entries for encyclopedias and reviews for The Nation to earn money. He even did translations for the Smithsonian Institution. Peirce also helped with mathematical calculations for research on powered flight. He tried inventing things, hoping to make money.

From 1890 on, he had a friend in Judge Francis C. Russell. This friend introduced Peirce to a philosophy journal called The Monist, which published many of Peirce's articles. He also wrote many texts for a big dictionary of philosophy and psychology.

His old friend William James helped Peirce a lot during these tough times. James dedicated his book Will to Believe (1897) to Peirce. He also arranged for Peirce to give lectures at Harvard. Most importantly, from 1907 until James's death in 1910, James asked his wealthy friends to give money to help Peirce. This fund continued even after James died.

Death

Charles Sanders Peirce died in Milford, Pennsylvania, in 1914. He faced financial struggles throughout his life. His wife, Juliette, kept his ashes at their home. In 1934, Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot helped arrange for Juliette's burial. Peirce's ashes were buried with her.

Important Discoveries

Peirce made many amazing discoveries in formal logic and foundational mathematics. Most of these were only truly understood long after he passed away.

- In 1860, he suggested a way to count infinite numbers. This was years before another mathematician, Georg Cantor, did similar work.

- In 1880–1881, he showed how Boolean algebra (a type of logic) could be done using just one simple operation. This was 33 years before Henry M. Sheffer made a similar discovery.

- In 1881, he created a set of rules for natural number arithmetic. This was a few years before Richard Dedekind and Giuseppe Peano.

- In the same paper, Peirce also defined what a finite set is. He also gave an important definition of an infinite set. An infinite set is one that can be matched up perfectly with one of its smaller parts.

- In 1885, he explained the difference between first-order and second-order quantification. In the same paper, he also created what can be seen as the first basic axiomatic set theory. This was about two decades before Zermelo.

- In 1886, he realized that Boolean calculations could be done using electrical switches. This was more than 50 years before Claude Shannon explored the same idea.

Interesting Facts About Charles Sanders Peirce

- When he was 12, Charles read a book on logic by Richard Whately. This started his lifelong interest in logic and how we reason.

- Peirce learned philosophy by reading a few pages of Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason every day. He read it in the original German while at Harvard.

- He worked on practical mathematics in areas like economics, engineering, and map projections. He was especially good at probability and statistics.

- Peirce was one of the people who helped create the field of statistics.

- In one of his writings, Peirce said that the most important rule for thinking is that "to learn, one needs to desire to learn."

- During his last two decades, he often couldn't afford heat in winter. He sometimes lived on old bread given by a local baker.

- Because he couldn't afford new paper, he would write on the back of his old notes.

See Also

In Spanish: Charles Sanders Peirce para niños

In Spanish: Charles Sanders Peirce para niños

- Howland will forgery trial

- Hypostatic abstraction

- Charles Sanders Peirce § Notes

- Laws of Form

- List of American philosophers

- Logical machine

- Logical matrix

- Mathematical psychology

- Charles Sanders Peirce § Notes

- Peircean realism

- Pragmatics

- Charles Sanders Peirce § Notes

- Charles Sanders Peirce § Notes

- Relation algebra

- Truth table

Contemporaries Associated with Peirce

Images for kids

-

"The World on a Quincuncial Projection", 1879. Peirce’s map projection keeps angles true except at four points, and has less scale variation than the Mercator projection.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |