Critique of Pure Reason facts for kids

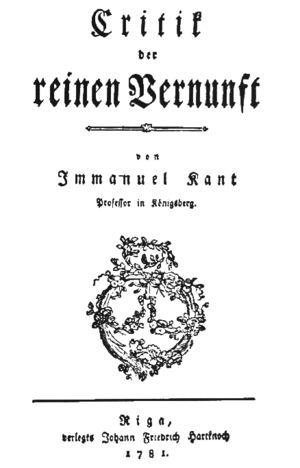

Title page of the 1781 edition

|

|

| Author | Immanuel Kant |

|---|---|

| Original title | Critik a der reinen Vernunft |

| Translator | see below |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Metaphysics |

| Published | 1781 |

| Pages | 856 (first German edition) |

| a Kritik in modern German. | |

The Critique of Pure Reason (German: Kritik der reinen Vernunft) is a famous book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. It was first published in 1781, with a second edition in 1787. In this book, Kant explored the limits of human reason and what we can truly know about the world. He wanted to figure out if metaphysics – the study of basic things like existence, knowledge, and reality – could be a real science.

Kant's work built on ideas from earlier philosophers. He looked at empiricists like John Locke and David Hume, who believed knowledge comes from experience. He also studied rationalists like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who thought knowledge comes from reason. Kant introduced new ideas about space and time. He also tried to solve problems raised by Hume about cause and effect, and by René Descartes about knowing the outside world.

Kant said that some knowledge comes from experience (this is called a posteriori). For example, knowing that it's raining outside is a posteriori because you have to look outside to know it. But other knowledge comes from our minds, independent of experience (this is called a priori). For instance, knowing that 2+2=4 is a priori because you don't need to see two apples and two more apples to know the answer. According to Kant, a priori knowledge is always true and applies everywhere.

He also talked about two types of statements: "analytic" and "synthetic." An analytic statement is true by definition. For example, "All bachelors are unmarried." You know this is true just by understanding the word "bachelor." A synthetic statement adds new information. For example, "All bodies are heavy." The idea of "heavy" isn't part of the definition of "body." Before Kant, many philosophers thought all a priori knowledge had to be analytic. But Kant argued that some important knowledge, like in math and science, is both a priori and synthetic. This led to his main question: "How are synthetic a priori judgments possible?" Answering this was crucial for understanding how we know things.

When it first came out, the book didn't get much attention. But later, it became very important and influenced a lot of Western philosophy. It's seen as a key work that connects older philosophy with newer ideas.

Contents

How We Know Things: Kant's Big Idea

Kant was inspired by David Hume, who doubted if we could truly know things like cause and effect. Hume thought we only see one event follow another, not that one causes the other. This made Kant wonder how we can be sure about basic principles.

Kant realized that Hume's ideas challenged how we understand the world. He spent many years thinking about it. His book, written quickly, was the result of all that deep thought. Kant wanted to find a way to explain how we know things like cause and effect without just relying on what we see or hear.

Our Minds Shape Reality

Kant believed that our minds aren't just empty containers waiting for information. Instead, our minds actively shape how we experience the world. Think of it like wearing special glasses that always make everything look a certain way. You can't see the world without those glasses.

He called this idea transcendental idealism. It means that objects we experience (what he called "appearances") are shaped by the way our minds work. Things like space and time aren't just out there in the world independently. Instead, they are ways our minds organize what we sense.

This is a bit like a "Copernican Revolution" in philosophy. Just as Nicolaus Copernicus showed that the Earth revolves around the Sun (instead of everything revolving around Earth), Kant suggested that objects must fit our way of knowing them, rather than our knowledge simply fitting objects. This means our knowledge depends not just on the object, but also on how our minds process it.

The Building Blocks of Knowledge

Kant divided his book into two main parts: the "Doctrine of Elements" and the "Doctrine of Method."

How Our Senses Work: Transcendental Aesthetic

The first part, the Transcendental Aesthetic, looks at how our senses work. Kant argued that space and time are not things we learn from experience. Instead, they are "pure forms of intuition" that are already built into our minds. They are like the basic framework or template our minds use to organize all the information we get from our senses.

For example, when you see a tree, your mind automatically places it in space (it's over there) and time (it's happening now). You don't have to learn what space and time are from seeing trees; your mind already uses these concepts to make sense of the tree.

How Our Understanding Works: Transcendental Logic

The second part, the Transcendental Logic, explores how our understanding works with concepts. Kant said that knowledge needs two things:

- Intuitions: The raw information we get from our senses (like seeing the color red).

- Concepts: The ideas our minds use to organize that information (like the idea of "redness" itself).

Just as space and time are the basic forms for our senses, Kant believed there are basic concepts for our understanding. He called these categories.

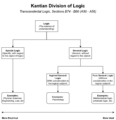

The Categories: Our Mind's Tools

Kant identified twelve basic categories, like "cause and effect," "substance," and "existence." These are like the fundamental tools our minds use to make sense of the world. For example, when you see a ball hit a window and the window breaks, your mind uses the "cause and effect" category to understand that the ball caused the break.

These categories are not learned from experience; they are built into our minds. They are what make it possible for us to think about and understand objects.

What We Can't Know: Transcendental Dialectic

In the Transcendental Dialectic, Kant showed what happens when we try to use these categories and our reason to understand things beyond our experience. He argued that our reason naturally tries to find answers to big questions like:

- Does every person have an immortal soul?

- Does the universe have a beginning in time and space?

- Does God exist?

Kant showed that when we try to answer these questions using pure reason alone, we run into problems. He called these problems "antinomies" (meaning two opposing but seemingly logical arguments) and "paralogisms" (false reasoning).

Can We Prove God Exists?

Kant famously argued that you cannot prove God's existence (or non-existence) using pure reason. He looked at common arguments for God's existence:

- The Ontological Proof: This argument says God must exist because He is perfect, and a perfect being must include existence. Kant said this is wrong because "existence" isn't a quality or a feature like "tall" or "wise." It's just saying something is real. You can imagine a perfect pizza, but that doesn't make it exist in front of you.

- The Cosmological Proof: This argument says that since everything has a cause, there must be a "first cause" or a "necessary being" (God). Kant argued that this proof also relies on the ontological proof, and it uses the idea of "cause" outside of our experience, which isn't allowed.

- The Physico-theological Proof: This argument looks at the amazing design in nature and concludes there must be an intelligent designer (God). Kant said this argument can show there's a very powerful and wise designer, but it can't prove that this designer is the all-perfect, all-knowing God of religion.

Kant's point was not to say that God doesn't exist, but that our human reason, by itself, cannot prove or disprove God's existence. These questions are beyond what we can know through experience or pure logic.

How to Use Reason: Transcendental Doctrine of Method

The second main part of the book, the Doctrine of Method, explains how we should properly use our reason.

The Discipline of Pure Reason

Kant said that philosophy should be careful and not try to make claims about things beyond what we can experience. Unlike mathematics, which uses ideas that are true a priori (like in geometry), philosophy needs to connect its ideas to things we can actually sense. If philosophy tries to go beyond experience, it becomes "dogmatic" – meaning it makes claims without proper proof.

Kant also argued against using reason in "polemics" (arguments where people try to prove or disprove things like God's existence without relying on experience). He believed that such arguments can't be settled because they go beyond what we can truly know. Instead, he encouraged open discussion and "criticism" – examining the limits of our knowledge.

The Canon of Pure Reason

Even though we can't use pure reason to know about God, an immortal soul, or free will, Kant believed these ideas are very important for our moral lives. He said that reason helps us answer three big questions:

- What can I know? We can only know things that can be experienced by our senses.

- What should I do? We should act in a way that makes us worthy of happiness.

- What may I hope for? We can hope for happiness if we act morally.

Kant suggested that our moral sense leads us to believe in God and a future life where good actions are rewarded. These beliefs aren't based on scientific proof, but on a "moral certainty" that helps us live good lives.

The Architectonic of Pure Reason

Kant saw all knowledge from pure reason as fitting together like a well-designed building (an "architectonic" system). He believed that philosophy, especially metaphysics, helps us understand the foundations of science and guides us toward wisdom and happiness. It helps us see the limits of our reason and how it connects to our moral lives.

Key Ideas and Terms

To understand Kant's book, it helps to know some of the terms he used:

- A priori: Knowledge that comes from our minds, independent of experience (e.g., math facts).

- A posteriori: Knowledge that comes from experience (e.g., knowing it's raining).

- Analytic: A statement that is true by definition (e.g., "All triangles have three sides").

- Synthetic: A statement that adds new information (e.g., "The sky is blue").

- Appearance: How things seem to us, shaped by our minds.

- Category: Basic concepts (like cause and effect) that our minds use to organize experience.

- Intuition: Direct sensing or perception of something.

- Phenomena: The world as it appears to us, shaped by our senses and understanding.

- Noumena: The world as it is "in itself," independent of our minds, which Kant said we cannot know.

- Transcendental idealism: Kant's idea that our experience of reality is shaped by the structure of our minds.

Intuition and Concept

Kant explained that our minds use two main types of "representations" (ways of thinking about things):

- Concepts: These are general ideas that help us understand things. For example, the concept "chair" helps us recognize many different chairs.

- Intuitions: These are direct experiences. When you see a specific chair, that's an intuition.

He also said intuitions can be "pure" (like our sense of space and time, which don't involve specific sensations) or "empirical" (like seeing a chair, which involves sensations like color and shape).

Tables of Principles and Categories

Kant organized his ideas into tables to show how different types of judgments and concepts relate to each other. He believed these categories are the fundamental ways our understanding works.

| Function of thought in judgment | Categories of understanding | Principles of pure understanding |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Quantity | |

| Universal Particular Singular |

Unity Plurality Totality |

Axioms of Intuition |

| Quality | Quality | |

| Affirmative Negative Infinite |

Reality Negation Limitation |

Anticipations of Perception |

| Relation | Relation | |

| Categorical Hypothetical Disjunctive |

Of Inherence and Subsistence (substance and accident) Of Causality and Dependence (cause and effect) Of Community (reciprocity between the agent and patient) |

Analogies of Experience |

| Modality | Modality | |

| Problematical Assertorical Apodeictical |

Possibility-Impossibility Existence-Non-existence Necessity-Contingence |

Postulates of Empirical Thought in General |

Images for kids

See also

- Arthur Schopenhauer's criticism of Immanuel Kant's schemata

- Cosmotheology

- Object-oriented ontology

- Kant's antinomies

- Noogony

- Noology

- Ontotheology

- Phenomenology (philosophy)

- Philosophy of space and time

- Romanticism in philosophy

- Transcendental theology

- Transcendental subject

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |