Charles William Eliot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

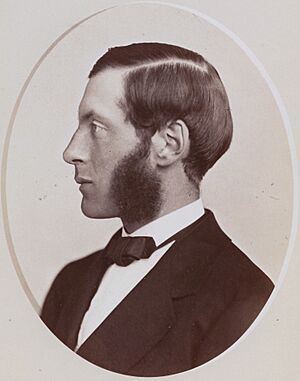

Charles William Eliot

|

|

|---|---|

Eliot c. 1904

|

|

| 21st President of Harvard University | |

| In office 1869–1909 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Hill |

| Succeeded by | A. Lawrence Lowell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 20, 1834 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | August 22, 1926 (aged 92) Northeast Harbor, Maine, U.S. |

| Spouses | Ellen Derby Peabody (1858–1869) Grace Mellen Hopkinson (1877–1924) |

| Relations | Eliot family |

| Children | Charles Eliot Samuel A. Eliot II |

| Parent | Samuel Atkins Eliot |

| Alma mater | Harvard College |

| Profession | Professor, university president |

| Signature | |

Charles William Eliot (born March 20, 1834 – died August 22, 1926) was an important American educator. He served as the president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909. This was the longest time anyone has ever been president of Harvard.

Eliot came from a well-known family in Boston. He helped change Harvard from a respected local college into one of America's top research universities. Even Theodore Roosevelt, a former U.S. President, once said that Eliot was "the only man in the world I envy."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Charles Eliot grew up in the wealthy Eliot family in Boston. His father, Samuel Atkins Eliot, was a politician. Charles was the only boy among five children.

He went to Boston Latin School and then to Harvard University, graduating in 1853. After college, he became a math tutor at Harvard in 1854. He also studied chemistry. By 1858, he was an Assistant Professor of Math and Chemistry. He was good at teaching and wrote about chemicals in metals. He also worked on ideas to improve Harvard's Lawrence Scientific School.

Eliot really wanted to become a Chemistry Professor, but he didn't get the job. This was tough, especially because his family lost money in a financial crisis in 1857. He realized he had to rely on his teaching salary and money left to him by his grandfather. In 1863, Eliot left Harvard. Instead of going into business, he used his grandfather's money to travel and study education in Europe for two years.

Studying Education in Europe

When Eliot visited Europe, he didn't just look at schools. He wanted to understand how education helped countries grow. He paid attention to everything, from what was taught in classes to how buildings were cleaned. He was especially interested in how education helped with economic growth.

He saw how schools in France trained young people for jobs that needed scientific knowledge, like designing things for industries. He thought America needed similar schools to help its own industries grow. He wrote about how important it was for Massachusetts to support manufacturing.

Eliot also noticed that European universities often got money from their governments. He realized that American schools would need support from wealthy people. He believed that if Americans understood the need for skilled chemists and engineers, they would create the schools to train them.

While in Europe, Eliot was offered a high-paying job as a superintendent at a large textile mill. Even though his friends encouraged him, he turned it down. He realized he loved organizing and managing things, but he wanted to do it on a bigger scale. He saw that helping science and industry connect could have a much larger impact than just running one business. He wanted to help his country grow through both knowledge and industry.

Changes in American Colleges

In the 1800s, many American colleges were run by religious leaders. They mostly taught old subjects like Latin and Greek. These subjects didn't seem very useful for a country that was becoming more industrial. Few colleges offered classes in science, modern languages, or history. There were also very few graduate or professional schools.

Business leaders didn't want to send their sons to schools that didn't teach useful skills. They also didn't want to donate money to them. So, some educators started looking for ways to make higher education better. Some wanted to create special science and technology schools, like Harvard's Lawrence Scientific School or the new Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Others thought colleges should offer more job-focused classes.

Harvard was facing these challenges. After several short-term presidents, Boston's business leaders, many of whom were Harvard graduates, wanted big changes.

When Eliot returned to the U.S. in 1865, he became a professor at the new Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Around this time, a big change happened at Harvard. The power to choose Harvard's leaders (called overseers) was moved from the state government to the college's graduates. This made graduates more interested in how the university was run and helped prepare the way for major reforms. Soon after, Harvard's president resigned, and Charles Eliot became the new president in 1869.

Eliot's Harvard Presidency

In early 1869, Eliot wrote two articles called "The New Education" for a popular magazine. In these articles, he shared his ideas for improving American higher education. He believed that America needed well-trained and prepared people to face its challenges. These articles greatly impressed the business leaders who controlled Harvard. At just 35 years old, Eliot became the youngest president in Harvard's long history.

Eliot wanted education to help students make smart choices, but not just train them for one specific job. He believed that education should help people develop their character and use their intelligence to solve problems. He thought that by allowing individuals to fully develop their skills, they could help the whole country progress.

He planned to improve professional schools, grow research departments, and offer many more courses. For undergraduate students, he wanted to help them find their "natural talents." He believed that each person had a unique way of thinking. By offering many different subjects, students could discover what they were good at and what they enjoyed. Once they found their passion, they could focus on it.

Eliot said that a country's strength comes from having many different kinds of skilled people, not just everyone learning the same thing. He believed that focusing on one's special talent was smart for individuals, and having a variety of talents was good for the country.

Under Eliot's leadership, Harvard started an "elective system." This meant students could choose almost all their courses. This helped them explore different subjects and find their interests. Harvard also greatly expanded its graduate and professional schools, becoming a center for advanced scientific and technological research. Teaching methods also changed, focusing more on testing students' knowledge and grading their performance carefully.

Not everyone agreed with Eliot's changes. Some critics, like his relative Samuel Eliot Morison, felt that removing required classical subjects like Greek and Latin was a mistake. Morison believed that these subjects were important for mental training and cultural understanding. However, other scholars, like Richard M. Freeland, argue that Eliot understood Harvard needed to become more modern. Eliot believed that the old college system wasn't preparing leaders for the changing world. He wanted Harvard to focus on modern thinking and research, and to help talented people show their abilities.

Views on Sports

During his time as president, Eliot was not a fan of football. He even tried to ban the game at Harvard. In 1905, he called it "a fight whose strategy and ethics are those of war." He thought that players often broke rules and that the game encouraged stronger players to take advantage of weaker ones. He also believed that no sport was healthy if unfair actions helped win.

He also spoke out against baseball, basketball, and hockey. He once said that rowing and tennis were the only "clean" sports. He famously criticized baseball, saying that a "curve ball" was thrown to deceive, and that Harvard shouldn't encourage such trickery.

Attempts to Merge with MIT

Eliot tried many times to combine Harvard with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), even after he retired. MIT was a much newer school and often had money problems in its early years. It was saved by donations many times. However, the students, teachers, and alumni of MIT strongly opposed joining Harvard.

In 1916, MIT moved to new, larger buildings in Cambridge. There were still plans for it to merge with Harvard. But in 1917, a court decision stopped the merger. MIT eventually became financially stable on its own. Eliot was involved in at least five unsuccessful attempts to make MIT part of Harvard.

Personal Life

On October 27, 1858, Charles Eliot married Ellen Derby Peabody. They had four sons. One son, Charles Eliot, became a famous landscape architect and helped design Boston's public park system. Another son, Samuel Atkins Eliot II, became a Unitarian minister and led the American Unitarian Association for many years.

The famous poet T.S. Eliot was a cousin of Charles William Eliot and attended Harvard during the last years of Charles's presidency.

After Ellen died from tuberculosis at age 33, Eliot married Grace Mellen Hopkinson in 1877. They did not have any children.

Eliot retired in 1909 after 40 years as president. He was honored as Harvard's first president emeritus (a retired president who keeps their title). He lived for another 17 years, passing away in 1926. He was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Legacy and Impact

Under Eliot, Harvard became a globally recognized university. It started accepting students from all over America using standardized entrance exams. Harvard also hired well-known scholars from around the world. Eliot reorganized the university's departments and changed teaching methods from simple recitations to more interactive lectures and seminars. During his 40 years, Harvard built many new laboratories, libraries, classrooms, and sports facilities. Eliot also attracted money from wealthy donors, making Harvard one of the richest private universities in the world.

Eliot's leadership made Harvard a model for other American schools. He also played a big role in improving high school education. Many new elite boarding schools and public high schools designed their courses to meet Harvard's high standards. Eliot was also a key person in creating standardized college admissions tests, helping to start the College Entrance Examination Board.

As the leader of a famous university, Eliot was a well-known figure. People often asked for his opinions on many topics, from tax rules to public education. He also edited the Harvard Classics, a collection of books meant to provide a good education to anyone who read them, even for just 15 minutes a day.

Eliot was against American imperialism, which is when a country tries to expand its power by taking over other lands.

During his presidency, Eliot did not support women having the same educational opportunities as men. He believed that people didn't know enough about women's natural mental abilities. However, women still found ways to get an education through the Harvard Annex, where Harvard professors taught them. This program grew quickly and led to the creation of Radcliffe College. Even though Eliot had reservations, he eventually signed the degrees for women who graduated from Radcliffe, confirming that their degrees were equal to those from Harvard. He still thought that education for boys and girls should be separate.

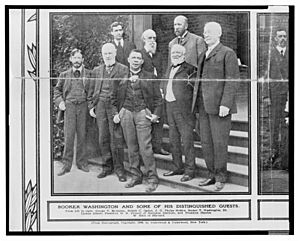

Many important "firsts" for African Americans in education happened during Eliot's time as president. Richard Theodore Greener was the first African American to graduate from Harvard. W.E.B. Du Bois was the first African American to earn a PhD from Harvard. Harvard also hired its first African American faculty member, George F. Grant. Despite these changes, Eliot held beliefs in racial segregation and eugenics.

Unlike his successor, Eliot was against limiting the admission of Jews and Roman Catholics to Harvard. However, he strongly opposed labor unions. He created an environment at Harvard where many students acted as strikebreakers (people who work during a strike to replace striking workers). Some even called him "the greatest labor union hater in the country."

Charles Eliot was a strong supporter of educational reform and many goals of the progressive movement. This movement aimed to improve society through government action and social change.

Eliot was also involved in helping others through philanthropy. He served on boards for organizations like the General Education Board, the International Health Board, and the Rockefeller Foundation. He helped start the Institute for Government Research (now the Brookings Institution). He was also a founding trustee of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He was involved with the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and served as vice president for the National Committee for Mental Hygiene. He was the first president of the American Social Hygiene Association and also led the National Civil Service Reform League.

For his 90th birthday, Eliot received congratulations from around the world, including from two U.S. Presidents. Woodrow Wilson said Eliot had made a huge impact on America's education system. Theodore Roosevelt repeated that Eliot was the only man he envied.

When he died in 1926, The New York Times published a full-page interview with Eliot, including his thoughts on education, religion, democracy, and other topics.

Today, a special teaching position at Harvard, the Charles W. Eliot Emeritus University Professor, is named in his honor.

Inscriptions by Charles W. Eliot

President Eliot wrote over one hundred inscriptions. These can be found on buildings like schools, churches, public buildings, memorial tablets, and monuments, including the Library of Congress. Here are a few examples:

ON THESE HEIGHTS

DURING THE NIGHT OF MARCH 4 1776,

THE AMERICAN TROOPS BESIEGING BOSTON

BUILT TWO REDOUBTS,

WHICH MADE THE HARBOR AND TOWN

UNTENABLE BY THE BRITISH FLEET AND GARRISON.

ON MARCH 17 THE BRITISH FLEET

CARRYING 11000 EFFECTIVE MEN

AND 1000 REFUGES,

DROPPED DOWN TO NANTASKET ROADS

AND THENCEFORTH

BOSTON WAS FREE,

A STRONG BRITISH FORCE

HAD BEEN EXPELLED

FROM ONE OF THE UNITED AMERICAN COLONIES

(From the Evacuation Monument at Dorchester Heights in Boston, Massachusetts, 1902)

TO THE MEN OF BOSTON

WHO DIED FOR THEIR COUNTRY

ON LAND AND SEA IN THE WAR

WHICH KEPT THE UNION WHOLE,

DESTROYED SLAVERY AND MAINTAINED THE CONSTITUTION.

THE GRATEFUL CITY

HAS BUILT THIS MONUMENT,

THAT THEIR EXAMPLE MAY SPEAK

TO COMING GENERATIONS

(From the Soldiers and Sailors Monument (Boston) on Boston Common, Massachusetts, 1877)

Monuments and Memorials

Eliot House, one of the student dorms at Harvard, was named after Eliot and opened in 1931. Several schools were also named in his honor, including Charles W. Eliot Middle School in Altadena, California, Eliot Elementary School in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Charles William Eliot Junior High School (now Eliot-Hine Middle School) in Washington, DC.

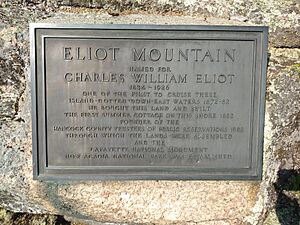

In 1940, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp honoring Eliot as part of their Famous Americans Issue. An asteroid, (5202) Charleseliot, is also named after him. Eliot Mountain in Maine was named for him because he spent summers there and helped create Acadia National Park.

Honors and Degrees

Charles W. Eliot received many honors and degrees throughout his life:

- 1857: Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1869: LL.D. from Williams College and Princeton University

- 1870: LL.D. from Yale University

- 1871: Member of the American Philosophical Society

- 1873: Member of the Massachusetts Historical Society

- 1879: American Library Association Honorary Membership

- 1902: LL.D. from Johns Hopkins University

- 1903: Officer of the Legion of Honor (France)

- 1904: Corresponding Member of the Academy Moral and Political Science, Institute of France

- 1908: Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown of Italy

- 1909: Imperial Order of the Rising Sun, 1st class; Royal Order of Merit of the Prussian Crown, 1st class; Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (England); LL.D. from Tulane University, University of Missouri, Dartmouth College, and Harvard University; MD. (honorary) from Harvard University

- 1911: Ph.D. (honorary) from University of Breslau

- 1914: Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy; LL.D. from Brown University

- 1915: Gold Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1919: Order of the Crown of Belgium

- 1923: Grand Cordon of the Order of St. Sava, Serbia; LL.D. from Boston University; Civic Forum Medal of Honor, New York

- 1924: Roosevelt Medal for Distinguished Service; Commander of the Legion of Honor (France); LL.D. from University of the State of New York

Books by Eliot

- The Training for an Effective Life (1915)

- Educational Reform: Essays and Addresses (1901)

- The Conflict between Individualism and Collectivism in a Democracy (1910)

See also

- History of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Lawrence Scientific School

Images for kids

-

"Blueberry Ledge" – Eliot's cottage in Northeast Harbor, designed by Peabody & Stearns

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |